SAWeekend Cover Story: Sonny Morey, SANFL star and Stolen Generation member and the nun who changed his life

A fortuitous meeting with a French nun more than six decades after he was stolen from his Indigenous family ended a lifetime of hurt and uncertainty for SANFL great Sonny Morey

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Boys home’s remarkable legacy

- Copping it Sweet: SA actor’s 40-year journey

- Best of the best: SANFL’s top 25 players

- Readers can reep rewards

With tears in his eyes, and shaking with emotion, the impact of what he had just discovered hit Sonny Morey. Finally, it made sense. His faith in humanity was restored.

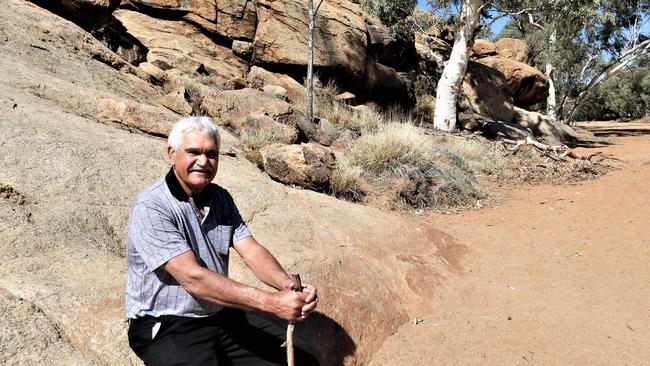

At last, he had an explanation for the unpalatable concept which had lingered quietly in the back of his consciousness for more than six decades. Ever since that horrible day he was bundled into a government car while playing on the dry bed of the Todd River in Alice Springs.

Morey, who would go on to become a champion SANFL footballer, was just seven when he became a member of the Stolen Generation, ripped from his community under a policy which destroyed the lives of countless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

In the decades to come, there was an uncomfortable question gnawing away at his soul. As time passed, he built a rich and rewarding life of his own. But the question was always there. Just below the surface. Casting an ever-so-slight shadow on his overwhelmingly positive disposition.

“Why hadn’t my mother come looking for me?”

And then, in August last year, under the midday sun in Central Australia, a petite 83-year-old nun with a thick French accent delivered the answer.

“Your mother searched for you until she died … she never gave up,” she said.

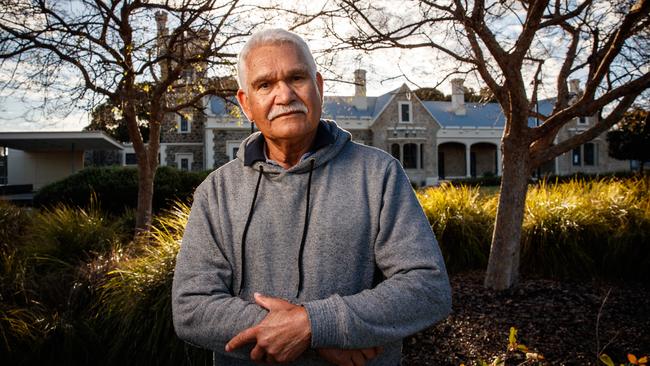

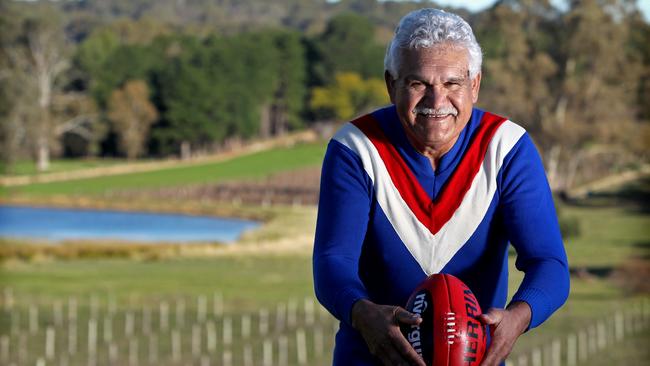

It was a simple sentence, but unleashed a complicated wave of emotions in Morey, a proud Arrernte man, Central District Football Club great, state player and runner-up to Malcolm Blight in the 1972 Magarey Medal.

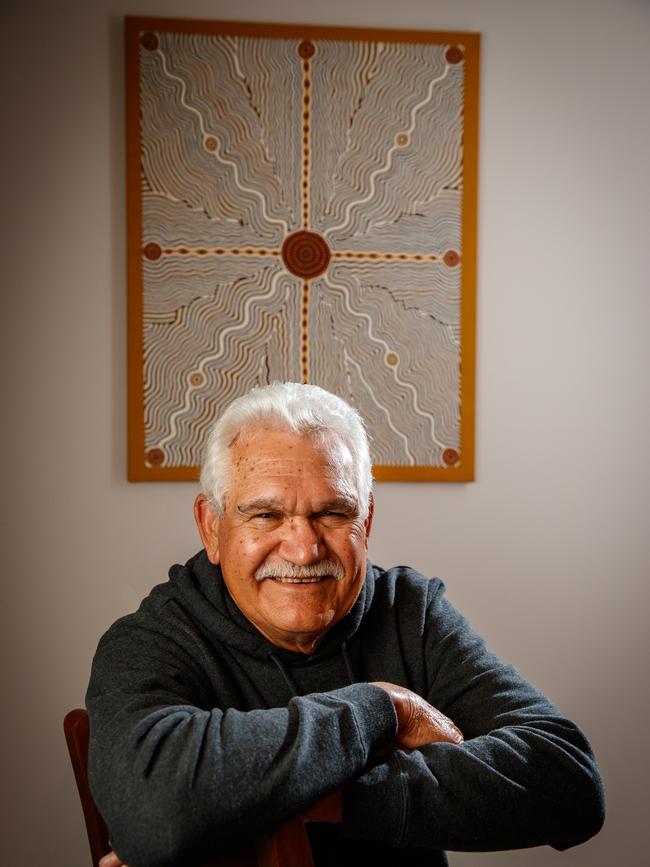

Over a cup of tea at his Williamstown home, which overlooks the vineyards of the southern Barossa Valley, Morey struggles to find words to describe that moment.

“I thought, when I was a little bloke, that my family had ignored me or abandoned me or weren’t looking for me,” he says. “To find that out, and at this time of my life … I don’t get too emotional because I’ve had to toughen up and harden up because of what I went through. But I found that difficult. Very difficult.”

The nun’s name was Sister Megali and Morey had only learnt she was still alive the previous day. He was on a fact-finding mission in Central Australia with biographers Robert Laidlaw and Robin Mulholland, trying to learn more about his stolen past.

The one-time silky smooth wingman and dashing defender had been on previous undertakings to Alice Springs many times but with limited success. This time, however, he struck gold.

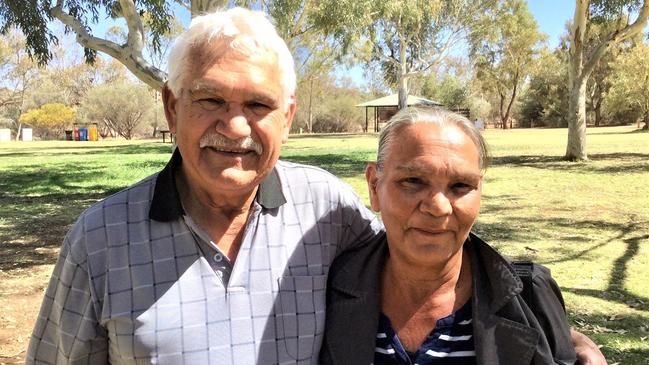

Over the past few decades he had discovered and come to know his sister, Phyllis Gorey. The pair had different mothers but shared the same father, a white Irish station owner called Tom Gorey.

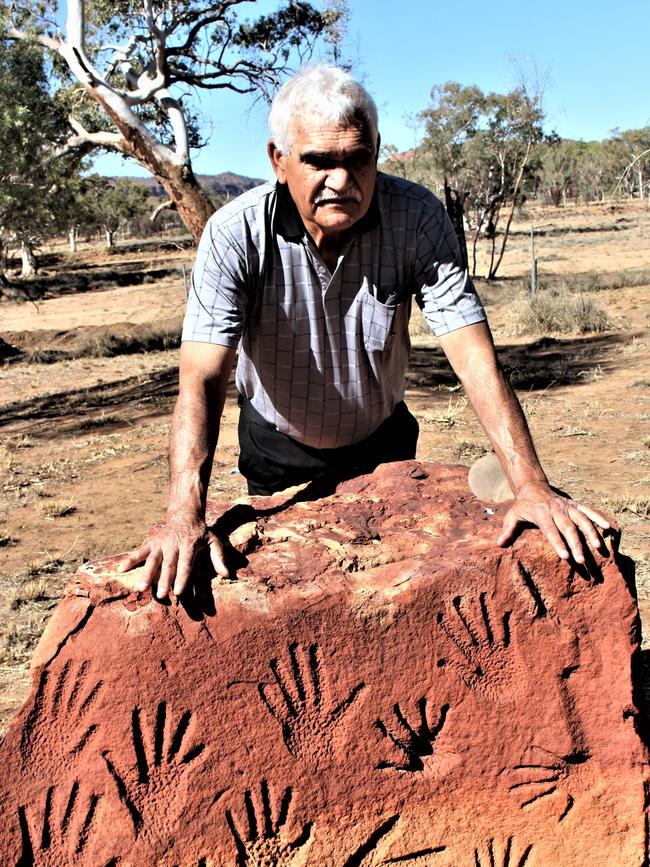

During their serendipitous Alice Springs tour last year, Morey, Laidlaw and Mulholland met Phyllis near the banks of the Todd River, not far from the spot where Morey was kidnapped back in 1952.

Their conversation turned to Megali, who had arrived in Alice Springs in the late 1950s as a missionary to offer guidance to the Indigenous population. Morey had a vague knowledge of Megali, and now his sister told him how close the nun had become to his mother, Nancy Pununga, and other women of her tight-knit community.

If he could find her, Phyllis suggested, Megali might be able to shed some light on Nancy, and how the abduction of her firstborn son affected her life. But Phyllis did not know if Megali now lived in Adelaide, Alice Springs, or was even still alive.

Later that day, Morey and his biographers discussed their quest over lunch in a nearby shopping mall when an Aboriginal woman, who had been quietly solving a Sudoku puzzle on a nearby table, overheard and joined the conversation.

It turned out Morey had met the woman, Bessie Parsons, at a Stolen Generation reunion more than 20 years ago. Their links went back even further – Morey and Parsons had both lived at St Mary’s Hostel in Alice Springs after they were removed from their families.

Parsons knew some of Morey’s family history, knew of Megali and suggested a priest at a nearby Anglican Church who might know more about the French nun’s whereabouts.

So the Adelaide trio knocked on the door of the rectory at the Anglican Church of Ascension, where they met Cannon Brian Jeffries who confirmed that yes, Megali was still alive. She was retired in Alice Springs but no, he did not know where she lived.

The next day the trio visited the nearby Catholic presbytery, where a courteous parish secretary provided both a phone number and an address.

Laidlaw and Mulholland take up the story in their biography which will be launched at Central District Football Club on Saturday: “Sonny’s anxious moments turned to pure joy as, at long last, he and Sister Megali embraced in a warm bear hug,” they write. “There was something very touching seeing well-built and still athletic-looking Sonny smothering this tiny, frail nun in his arms.”

Within a few minutes of conversation, a lifetime of uncertainty and disappointment lifted from Morey, as he discovered that Megali had spent years searching for him at the request of his mother and her family.

The search had proven futile, primarily because she had been looking for a man with a last name of Gorey, not Morey. When he was removed from his family, authorities had quietly changed Sonny’s last name, probably to remove all ties with his station-owner father.

The persistent Megali had tracked down a man called John Gorey in America but could not find Morey and eventually reported to the family that she thought she was chasing a ghost.

The revelation that his mother had been searching for him her entire life sparked a flood of relief for Morey, who had struggled for more than 60 years to comprehend that she would have abandoned him.

“It wasn’t only relief, but belief in people,” he tells SAWeekend, when asked to explain how his perspective on life changed during that one brief conversation. “And the belief that mothers will never give up on their child. And when you think about it, they carry them … they’re the carriers of life. And for someone to just give it up … that’s not on. And I then realised that.

“I always thought that, somewhere in the back of my mind, they would never give up. But to find out that my mother never threw the towel in, she was always looking for me, that was very important to me, and to my girls … my daughters.”

FATHER, GRANDFATHER, HUSBAND

Morey is now 75 and the walls of his comfortable semirural home are peppered with framed pictures of the family he holds so dear.

He and wife Carmel will celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary in December. They are proud parents of daughters Kim and Nicole, grandparents to Christopher, Michael, Tarnee and Kyan, and will welcome their first great-grandchild in November.

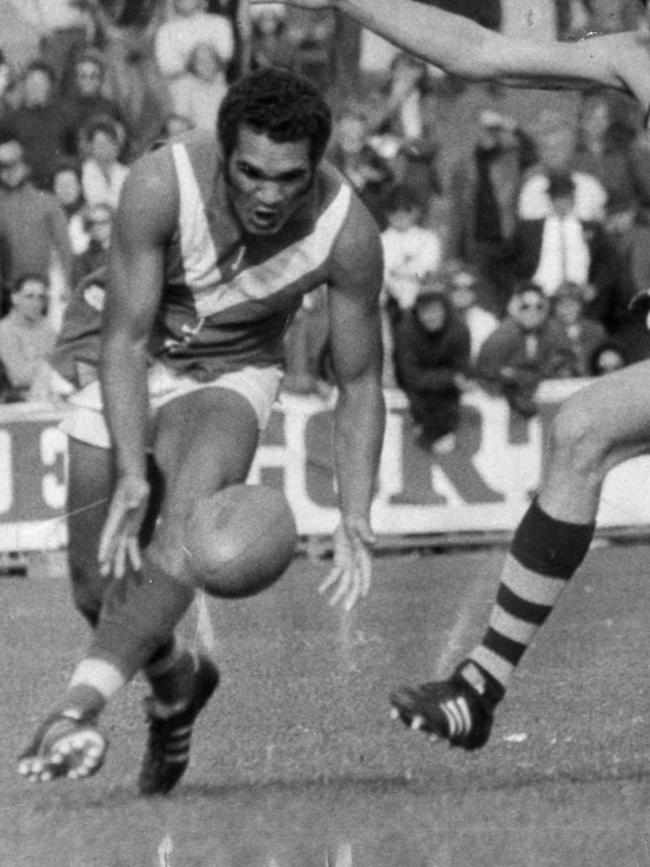

He plays golf twice a week at the nearby Sandy Creek Golf Club and remains a keen supporter of the Central District footy club, where he is much-loved. He made his debut in the club’s first ever league team, against West Torrens, in 1964, had the first kick of that game (it would have been a goal too, he says, if not for an Eagles player camped in the goalsquare), was the first Bulldog to play 200 games and was a household name during halcyon days of the SANFL.

He won plaudits as a clever wingman when he was club best and fairest in 1970, and had transformed to a dashing back pocket when he was runner-up to Blight in the league’s most prestigious award two years later. By the time he retired in 1977 he had clocked 213 league games and four state games in a career which earned him selection in a Central District best team of 1964-2003.

He coached Eudunda for three years after retiring from league footy and became the first Indigenous premiership coach in the Barossa and Light association before returning to lead the Central District under-17s side for a decade, mentoring many players who would go on to have significant SANFL and VFL careers.

Outside of football, Morey completed an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner with the Postmaster General’s. He spent 30 years with PMG and then Telecom, where he finished as a foreman before taking a separation package during a restructure.

He managed Gawler Sportspower for former teammate Tom Zorich for 12 months before accepting an approach to join SA Police as a community police officer to help bridge the gap between Aboriginal communities and the police. After a 13-year career at SAPOL, Morey retired in 2006 and then worked on the Australian Crime Commission’s investigation into child abuse in outback NT and WA for six months.

STOLEN

At Morey’s home, hanging proudly in the hallway in a location that’s impossible to miss, is an Aboriginal dot-art painting called Inerte – an original work created by his Alice Springs sister Phyllis – which depicts three generations of Aboriginal women travelling to bean tree locations.

It’s a permanent and prominent reminder of a heritage which he almost lost when two strangers, a man and a woman, approached him and his cousin John Leo on a balmy day in 1952.

“As kids we just used to run up and down the Todd River and play,” Morey says. “It didn’t matter when you came home because the family had no fear that anybody in their right mind would want to pinch a kid in that part of the world.” He’s referring to the tradition of Aboriginal communities acting as one to ensure the safety of their children.

“But the welfare system was totally outside of that, and they saw an opportunity, and bang, I was gone. It was virtually kidnapping. I was gone. I didn’t see John again. He was just left there crying.”

John Leo was a year older than his cousin. He lived with the unfounded shame and unreasonable blame of that moment for the rest of his life and turned to alcohol to ease the hurt.

Morey is convinced his father was complicit in the events of that day. In fact, he thinks Tom Gorey was probably the instigator, using a government policy as a vehicle to rid himself of an embarrassing illegitimate son.

As the existence of his sister Phyllis attests, the station owner was a repeat offender when it came to dalliances with the Aboriginal women who worked on his property, and it was a practice heavily frowned upon.

Interracial relationships were outlawed across much of northern Australia in the first half of the 20th century, and Morey believes his father tipped off government authorities looking to collect and institutionalise the products of such relationships, ostensibly with a purpose of providing the children with a civilised upbringing.

Morey can’t remember much of what happened after he was thrown into that dark government sedan, apart from seeing his cousin crying as they drove off.

“From that point onwards, everything was just blank, because I was terrified,” he says. “Over the years I’ve learnt to control that fear but that was just an horrific moment. I can still feel it now. It is a very unpleasant feeling.

“You think, ‘Jeez, I’m gunna die’. I thought I’d done something wrong – but I didn’t know what it was … It was very difficult. To look back on it now, it seems a bit easier, but, at the time, it was very, very ordinary.”

For years, he lived with an overwhelming feeling of guilt. To be targeted like he was, he figured, he must have committed a serious wrongdoing.

But he was just another victim of a raft of misguided government policies which a 1997 Bringing Them Home report estimated removed at least 100,000 Aboriginal children from their parents.

“As a nation, it’s something that’s part of the history and we’ve got to learn with it and understand it,” Morey says. “But what sort of mental health issues has this caused to people all across the country? This is profound. There were people removed willy nilly. This was the Aboriginal community Australia-wide. This is a problem.”

And so Morey became a ward of the state. For six years he lived under the strict regime of the Australian Board of Mission’s St Mary’s Hostel in Alice Springs.

The confusion of his abduction was compounded by the fact that he only spoke Arrernte, so did not understand the strange language everyone at St Mary’s spoke.

“I felt like I was abandoned by my family, because I thought they’d come anytime and I’d go home,” he says. “But that didn’t happen. And so, as you get older, you think your family has lost interest in you, and so you move on.”

He dedicated himself to reading hundreds of books to help get a handle on the English language, but in the process lost his grasp on his native tongue, a consequence he looks back on with regret.

“If you lose your language, you lose your identity. You lose who you are,” he says.

And then, in 1958, without warning or explanation, he and two other boys (Peter Butcher and Wally Gardener) were bundled into a plane and flown to Adelaide. It was another moment of unfathomable trauma and upheaval. But this time, there were no feelings of guilt.

“Not this time. This time, I was just trying to figure out: ‘Why are they taking me? All the other children are left. Why just me and these other two guys? Why us?’.”

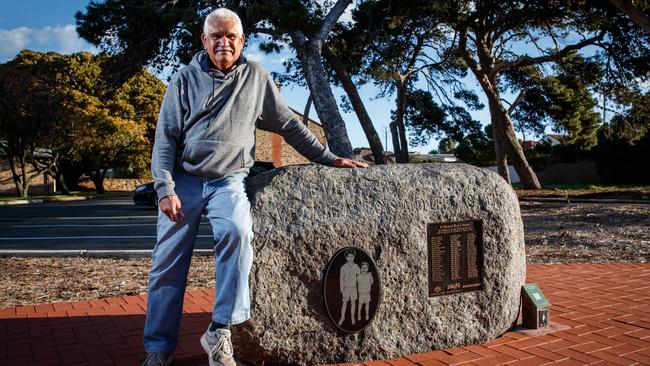

It’s a question he still can’t answer, but the move brought him to St Francis House in Semaphore – another Board of Mission’s home charged with caring for Aboriginal boys taken from their parents.

The home’s list of former residents reads like a Who’s Who of significant Indigenous figures and included future soccer stars, activists and artists Charlie Perkins, John Moriarty and Gordon Briscoe. Harold Thomas, who would go on to design the distinctive Aboriginal flag, was also among their number. As was Vince Copley, who played football for Port Adelaide.

The St Francis House building is now called Glanville Hall and used for weddings and events, but when the home for Aboriginal boys closed in 1959 it left its remaining residents without lodging.

Morey was among the soon-to-be-homeless boys photographed for a newspaper article which highlighted their plight.

World War II veteran Sydney Maguire and his wife Ada were living in Gawler when they saw the story in The News. The couple already had three children but decided to take in Morey as their adopted son.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

And so, the then 14-year-old Morey experienced his third massive upheaval. But his introduction to traditional caucasian family life continued a distressing pattern of traumatic life experiences. He had entered a home rife with domestic violence. He remembers Sydney Macguire not as a father figure, but more of a drunk and a wife basher.

“That was something that I never expected. I came from a home where there was only kids – the adults were just people who came and told you what to do and boss you around. I found it hard to come to terms with domestic violence.”

Ada Maguire eventually summoned the courage to leave her abusive husband and moved with her adopted son into a house near the Gawler football oval where Morey was already making a name for himself.

By the time he was 17, he had won two A Grade best and fairests at Gawler Central Football Club and in 1964, two weeks before his 19th birthday, was part of the first Central District SANFL league team.

He reckons the resilience he was forced to learn during his childhood held him in good stead on the footy field, where he was also often the subject of racial abuse from both opposition players and supporters.

“I got called some awful names – but that’s not gunna kill you if they call you names,” he says. “I look at it this way: I’m not a racist. I treat everybody the way I want to be treated and if the individual is a racist, they have a problem. They have to get over it, not me.”

But don’t the comments hurt?

“Nah, nope. I’ve been through all this (his traumatic childhood) so nothing anybody yells at me is going to make any difference to me.”

Mulholland and Laidlaw are both also stalwarts at Central District. The former, an Irish immigrant, played against Morey during the 1963 Gawler league grand final, and joined him at the Dogs from 1968-1974. Laidlaw is a well-known journalist and author in the Gawler and Barossa region, and is the Central District club historian. They were both blown away by the fateful turn of events during their visit to Alice Springs last year.

“Sonny always talks about spirituality, not in a sloppy way, just to make you know the deep feelings that Aboriginals have for each other and for the country,” Mulholland says.

“But we had a series of coincidences … where one thing led to another as if it was meant to happen. Maybe there was something deeper at play here. Something we don’t understand.”

The biography is the 17th book Laidlaw has either written or co-written. Nearly all have been about sport. But he knows this story is much broader than simply football. “It was almost like Sonny’s mother Nancy was looking over our shoulder, because everything just fell into place,” he says. “I think Sonny’s story is just so special. Sonny Morey is probably the best story I’ve been involved with in football.”

Sonny: Sonny Morey’s Inspirational Stolen Generation Story, written by Robert Laidlaw and Robin Mulholland, edited by Peter Cornwall, was published with help of a State Government grant. It is available through the Central District Football Club’s online store.