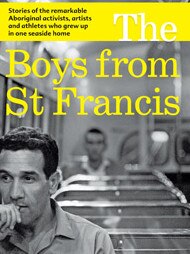

Author Ashley Mallett’s new book tells how a group of Aboriginal boys survived and thrived at St Francis boys’ home

A NEW book tells how a group of Aboriginal boys brought to Semaphore survived and thrived to find success as indigenous role models.

THERE’S a building in Semaphore called Glanville Hall. It’s near the beach, beside sprawling lawns. Built in 1856 by Captain John Hart, who was briefly South Australian premier, it’s a grand Victorian Tudor residence.

It’s had a varied existence – today a venue for weddings and events – but between 1947 and 1959 it was called St Francis and was a home for Aboriginal boys.

And out of that comes a remarkable tale. Some of the most influential names in recent Aboriginal history were residents at St Francis. The activist and soccer player Charlie Perkins, Harold Thomas who designed the Aboriginal flag, the artist John Moriarty who was also the first indigenous player picked for the Socceroos, and Vince Copley, a community leader who played for Port Adelaide and was a cricket administrator. There were others. Wally McArthur was a speed machine who became a rugby league legend in England. Gordon Briscoe was the first indigenous person to be awarded a PhD in the study of history.

Five of the kids who stayed at St Francis would become members of the Order of Australia. Their story has now been documented in a new book by former Test cricketer Ashley Mallett called The Boys from St Francis. Mallett, a prolific author with more than 30 books, believes his latest is the most significant work in a long career.

“I just found it a fascinating story,” he says. “I found it draining emotionally. There is a lot of love in the story, but there is a lot of sadness, a hell of a lot of sadness.”

But, as Mallett writes it, there is also joy, friendship and triumph.

Like many others, he was entirely unaware of the St Francis story, until Vince Copley asked him to take a look at it. That was in 2012 and Mallett had just finished his book on the 1868 tour of England by an Aboriginal cricket team called The Black Lords of Summer.

The new book has been a labour of love and has taken Mallett all over Australia trying to track down the boys of St Francis.

The story starts with an Anglican priest called Father Percy Smith. In 1945, Smith took six Aboriginal boys to a new life in Adelaide from Alice Springs. All went with the blessing of their mothers who believed they were sending their sons to a brighter future. Smith’s idea in establishing St Francis was that it would give the boys a better chance in life. They would be fed and clothed. They would be educated. In essence, they would, in the vernacular of the day, be assimilated into white society. The intention of the policy of assimilation was to teach indigenous people to be more “white” and Mallett is scathing of the hurt it caused.

“Even though they were expected to act like ‘whites’, assimilation never gave Aboriginals the same rights as other Australians. Assimilation was an abject failure, but it did leave its mark, an ugly scar on the collective Indigenous psyche,” he says.

The first six boys, which included Charlie Perkins, went voluntarily with Smith. But that wasn’t always the case and St Francis would also become home to members of the stolen generations. In total, 50 Aboriginal boys would call St Francis home over its lifespan.

Some of the most moving parts of Mallett’s book are the descriptions of the devastation visited on families when their children were taken away by the authorities.

John Moriarty was one of the boys taken unwillingly from his mother. He was four years old when he was stolen, taken from the Roper River Mission in the Northern Territory and moved first to Mulgoa in New South Wales before heading to St Francis. For 11 years he didn’t see his mum, despite many attempts to re-establish contact. As Mallett tells the story, when Moriarty was 15 he was taken back to Alice Springs for a visit.

“Then something incredible happened,” Moriarty says in the book. “Across the road this lady was looking at me with a very fixed look. And she strode across the road. I was similarly transfixed.”

She asked him a simple question.

“What’s your name?”

“John Moriarty.”

“She said, ‘I’m your mother.’”

“We sat down in front of a hotel, on the kerbside, and talked about my grandparents and the family back in Borroloola. It was a wonderful reunion for me and such a relief.”

Not all the boys were so lucky. Max Wilson was taken from Alice Springs, separated from his parents and brothers, and sent to St Francis. When he was 14 he received a telegram telling him his mother was gravely ill. He asked for permission to go and visit her. That was denied. Three weeks later another telegram arrived telling Wilson his mum had died.

“Again I asked for permission to travel to Alice Springs,” Wilson remembers. “But I was told ‘Max, you can’t do anything to help. They will lower her into the ground and cover her in dirt…now, go to school.’

“I cried for weeks. And now, at the age of 73, after all this time, I still mourn the loss of my mum.”

There is a general view in the book that the initial intent of Father Smith was, if somewhat misguided, a genuine intent to help improve the lives of the children. The boys were housed and fed, and sent to Ethelton Primary and Le Fevre Boys Technical.

But after two years, Father Smith left St Francis, leaving the boys feeling abandoned. Worse, his replacements as superintendent tended to be brutal. Smith was replaced by a man called Taylor who dispensed rough justice through the liberal use of a metre-long rubber hose and regularly beat the boys.

Perkins was a particular target. The future activist and driving force behind the Freedom Ride in the 1960s to highlight Aboriginal dispossession, was already standing up against racism and injustice as a young boy, and suffered the consequences, being regularly left with bruises all over his body.

According to Gordon Briscoe, Taylor was a “sadist who revelled in the power he exerted over a bunch of hapless half-caste kids”.

The racism of the time is peppered through Mallett’s book. Not just against the boys who were part of the stolen generation. But there were protests against the kids going to a local school and there was the everyday indignities routinely visited on Aboriginal people.

There were exemptions for those who denied their heritage and family to make them more like a white person. When soccer players such as Moriarty, Wilson and Perkins were chosen for state teams they had to apply for permission to travel interstate.

Sport was a salvation for the St Francis boys though. A lot of natural talent flowed through the place. At first most gravitated to Australian rules, but a chance encounter with the round ball sent Perkins and Moriarty on a road that would end with them becoming professional players.

The tale goes that a bunch of the boys, including Perkins, Moriarty and Wilson, were watching the state under-18 soccer team train on an oval near St Francis. Some of them had never seen the game before and didn’t know what it was.

They were invited to have a game and promptly beat the state side 10-0.

The moment changed Perkins’ life. He started playing for local team Port Thistle, the first step in a career that saw him signed by English giant Everton.

“That year I played for the Scottish club (Port Thistle) in Adelaide,’’ Mallett quotes Perkins as saying. “I got on well with the club crowd. They treated me like a human being. That was where I first felt free, when I began to play soccer.”

Many of the St Francis boys would feel more comfortable in the soccer world. The clubs were founded largely by migrants and the boys felt the newcomers to Australia were less judgmental when it came to matters of race.

In other sports, the colour bar was still heavily enforced.

Wally McArthur did find fame as a flying rugby league winger in England but Mallett believes the racism of the day denied him even greater glory. Mallett says at 14 McArthur was the fastest boy in the world and four years later during the trials for the Olympic Games he wiped the field in the 440 yards, but still wasn’t chosen to travel to Helsinki. Mallett believes McArthur could have won a gold medal in Helsinki in 1956 but notes it would not be until the 1960s that Australia would select an Aboriginal athlete for the Olympics. “The reason he didn’t get in was he wasn’t the right hue,” he says. “It’s really sad.”

The Boys from St Francis is full of such stories. They are at once wonderful and tragic. A glimpse into an Australia of not really that long ago, which paints the society of the time in an unflattering light.

Mallett is hopeful that his book sheds light on a dark time in Australian society, a time when the treatment of the nation’s indigenous people was not too different to how black citizens were treated in apartheid South Africa. But he also believes it can be a book that helps heal the wounds of the past.

“It’s a pathway to help close the gap,” he says. “I feel this story should be told and should be in every classroom, especially primary school.”

He believes younger people today are far more open to learning about indigenous history.

“In my era we didn’t learn anything about all the massacres and that sort of stuff,” he says. “Young people want to know more…they want to know more about the history of Australia and this is an integral issue of Australia. The oldest civilisation in the world.”

The fact so many of these boys emerged from such a brutal and repressive system and society is something of a miracle in itself. And they did it despite the forces against them.

Mallett developed enormous admiration for the boys who went through St Francis. He believes those who succeeded did so because in the absence of anyone else they relied on each other – and to a great extent still do.

“They have this extraordinary bond, which I don’t think I have experienced before in any group,” he says. “They are there for each other all the time. They are great role models, not just for young Aboriginal kids, but for all young people.”