SA Weekend inside story: Premier Steven Marshall’s response to the coronavirus crisis, a task his mum says he was born to tackle

In the final part of our series examining SA’s response to the coronavirus crisis, Steven Marshall reveals the toughest decision he was forced to make – and why he thinks there’s a silver lining for our state.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Inside SA’s COVID-19 response, Friday: Grant Stevens

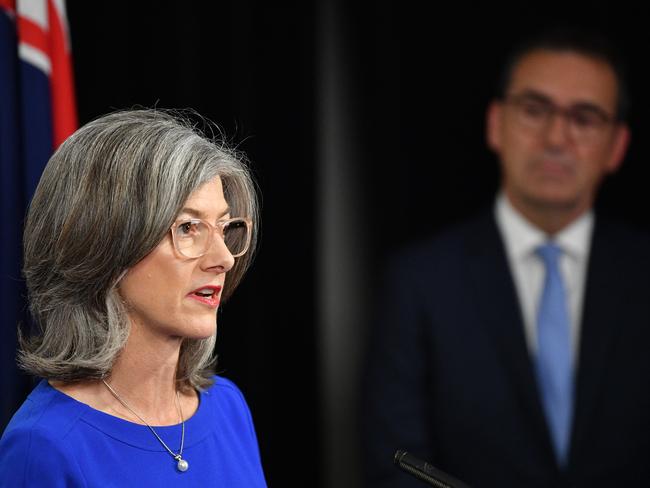

- Inside SA’s COVID-19 response, Saturday: Nicola Spurrier

- Inside SA’s COVID-19 response, Sunday: Stephen Wade

Steven Marshall was well into his COVID-19 routine by Monday, April 6.

Up at 4am, reading the news, going through boxes of papers, prioritising his day, texting his sleeping ministers.

But, two months into the coronavirus crisis, and heading into the Easter break, South Australia’s premier was about to get bad news – and face one of his toughest decisions.

Until that day, despite early warnings to Marshall that thousands of South Australians could die from the virus by Christmas, no one from the state had succumbed.

But then 75-year-old Frank Ferraro, a plasterer from Campbelltown, died at the Royal Adelaide Hospital after catching the bug at a Melbourne wedding.

“I was just dreading the day we had a South Australian pass away from this illness,” Marshall says in his 15th floor office overlooking Victoria Square, as he recalls key moments and decisions in the battle to date.

“We were one of the last states to record a death. It was probably inevitable, but nevertheless when it came it was still very numbing.”

Within a week, three others had died: a 62-year-old woman infected on the Ruby Princesscruise ship, a 78-year-old man who fell sick after Swiss tourists visited the Barossa Valley, and a second Ruby Princess passenger, aged 74.

Marshall wrote personally to all the families. “Every time you get out a pen to write a letter like that it really just hits home that yes, lives, families, massively disrupted. Yes, we should be grateful it was four; but four is still a tragedy.”

The deaths were a stark reminder of what was at stake. And they surely added impetus to a growing lobby that was privately pressuring Marshall to rethink one of the key elements of his COVID-19 strategy.

Asked about his most difficult decision, he says: “Easter was a tough choice. I was being very, very heavily lobbied to lock down my state internally, from very sensible people.”

The move to divide SA would have been a backflip on what Marshall had been doing: educating and informing people to do the right thing – stay home, maintain social distancing – rather than dictating and restricting movement by law.

“What we were strongly lobbied for was a legally enforceable grid system in the state,” he says, likening it to what Western Australia has imposed – currently five regions.

“You couldn’t get onto Kangaroo Island unless you were a resident, for example. This was being advocated by the local member and Leader of the Opposition. We should close off the Eyre Peninsula, we should close off the Yorke Peninsula, close off Robe.”

Marshall doesn’t name those lobbying him, describing them only as community leaders and concerned citizens. “It was the height,” he says.

“But as soon as you make something legally enforceable, there are other ramifications for people. I don’t know what it says about the human psyche, but you know we’re a contrarian lot: You tell somebody what to do and they’re going to tell you why that’s not a very good idea.

“But if you explain to them: This is the situation; this is how we’re all going to get through this together…” In the end, he stuck to his guns and trusted people to do the right thing, which he says they did.

South Australia has weathered the health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic extraordinarily well to-date, and, for the most part, had a less restrictive lockdown than many parts of Australia.

Crucial to the success were an intense world-leading testing program from SA Pathology and daily briefings from Chief Public Health Officer Professor Nicola Spurrier, who not only informed the state but won the public’s support and trust.

But managing the whole thing has been the 52-year-old Marshall.

Single, with two adult children, he has few distractions – and little downtime.

The year started with bushfires and quickly morphed into one of the biggest crises in the nation’s history.

“I realised very early … 2020 was not going to be a year for having a day off,” he says.

It’s clearly been wearing. Time has blurred for the premier, as it has for many of us. When we talk about the first cases in SA, he is convinced they were in March. It was February 1, I tell him.

“I just lost a month in there – wow!” he says, shaking his head.

But then, “every week feels like a month and every month feels like a lifetime”.

How’s he sleeping? Like a log, just not for very long. But he’s feeling fit.

He hasn’t been able to get to his gym – “I closed all the gyms!” – but he’s eating green vegetables, which he claims have ensured he’s never had a sickie in his life. And no, he hasn’t needed a COVID-19 test.

At a time of high anxiety, it’s handy to have a leader who presents an unflustered, hopeful image. Providing they know what they’re doing. In Marshall’s case, he blends a low-revving public manner and optimistic eye, and an industry background from running his family’s former furniture factory.

Early on he was shown numbers that made clear what was at stake.

“There were predictions that suggested we would have thousands of South Australians dead before Christmas,” he says. “That was pretty confronting. But at a time like that you don’t have a lot of time to think about your emotions. You think, ‘What do I need to do?’ There is no time to waste.”

So how did he approach a problem that was already overwhelming rich nations around the world? “Well, it’s funny because my mother sent me a message yesterday,” he says.

“She said, ‘I think you were born for this crisis’.”

Marshall says he thinks his mum, Barb, was talking about his personality. “I didn’t know if that was a compliment or not,” he says. “But I think I do remain calm.”

He also points to his experience before politics. “Coming from a manufacturing background, you always try to work out where you need to be and work backwards,” he says. “Have I got the resources to actually execute this? So, when we had to deal with all the capacity planning around health, that was just very logical for me. I think a lot of the building blocks that were critical to the management of this to date really suited my background.”

Marshall says he wanted to do better than stop the virus.

His late father Tony, who died in 2018, once told him “never waste a good crisis” and he didn’t intend to. The pandemic would give SA opportunities for the future, he thought. His ambition was for Australia to emerge as the best country in the world to handle the virus, and SA the best state in that country.

“And internally we developed this motto … we just said, ‘stronger than before’,” he says. “Our goal was never to limp across the line, or survive 2020, or to just get through the year. Our goal was to lean in against this pandemic. We did not want this to be a wasted year for South Australia, a year we could only take away from it terrible stories. And so, every member of cabinet, every minister, every chief executive, basically has had to demonstrate how we can make SA stronger than before.”

SA did have a pandemic plan back in February, even if it’s been constantly updated since; what it needed to find was time. “In Italy, people were dying because they didn’t have access to ventilators,” Marshall says. “These were unnecessary deaths, just because there was a mismatch between the demand for ECMO (life support machines) and ventilators versus the ability to supply. So doctors were being forced to make decisions: OK you get it, you don’t get it. We never wanted to get to that situation.”

SA’s strategy was to reduce the peak of people getting the disease and push that out into the future through world-leading testing, border closures, boosted contact-tracing teams and lockdowns of some businesses; to use that time to secure enough emergency equipment and protective gear, and ensure sufficient beds and staff; and educate the public about their role through crucial measures like social distancing.

While Marshall closed the SA borders in March to all but essential services, he decided against internal boundaries or limits, as in some other states. “One of the extraordinary things about what’s happened in SA is that we ended up with the lowest level restrictions but the highest levels of compliance with the principles of containing the disease,” he says. “In other places they went for a high level compliance and legal framework and they ended up arguing with their population in some circumstances.”

The big challenge was how to stop a health crisis without killing the economy – and whether he succeeds in that remains to be seen and will likely determine the result of the 2022 election.

Marshall says the two issues were interlinked but the virus had to be the priority.

“Priority one, from day one, was managing the health crisis,” he says. “And now it’s on a far more even keel.

“But in the early days we knew that the economic consequences of the health crisis getting away from us in SA would be absolutely catastrophic.”

Marshall deliberately didn’t take the lead in communicating to the public.

“In fact a lot of political types said, ‘I can’t believe when you had your 14 days with no outbreak that you didn’t (announce it) … other politicians would have had the confetti cannons going off and a big announcement, and you let Nicola Spurrier do it’. And I said, ‘Well that’s right. From day one, we all knew our role in the team’.”

He didn’t know Spurrier before the crisis but decided the best way to get the public to do their bit was by detailed medical briefings by experts.

“You know, politicians have a standard format,” he says. “We didn’t want that … We wanted high level public education, communication …”

Spurrier was perfect. She not only helped devise the government’s plan but sell it with her nonpartisan authority, like the state’s personal family GP. She was also given a regular seat at weekly cabinet meetings, along with the chief executive of SA Health Chris McGowan.

The pair, along with Health Minister Stephen Wade, were key connections between the cabinet and the public servants who provided the main advice on COVID-19. Key players included Police Commissioner Grant Stevens who, once a major emergency was called on March 22, became State Co-ordinator, with special powers to enforce compliance; Dr Tom Dodd, the clinical services director at SA Pathology, whose testing attracted interest from around the world; Dr Louise Flood, who ran the communicable diseases branch, chasing down contacts of those who’d tested positive; McGowan and, of course Spurrier, who each day also videoconferences with the other public health officers nationally.

Topping multiple SA Health groups co-ordinating the response was a leadership committee which had most of the main players including Wade.

“Everyone had their role to play,” Marshall says. “In one week, we had six cabinet meetings in seven days. We really did have a very joined up approach. I wasn’t making decisions on the fly that my cabinet would read about in the paper.

“Everybody knew exactly what we were doing. And each cabinet minister knew their role. So when Nicola Spurrier and Chris McGowan came to cabinet, and they still come every week, we went around the table and every minister would talk about the implications of what was happening in their portfolio.”

Marshall’s role also included representing SA at the newly formed national cabinet, which had its first meeting in mid-March. He strongly backs the national approach, and says he helped drive it.

“I certainly had suggested that we needed to meet more regularly,” he says. “COAG (the Council of Australian Governments) only meets once or twice per year. So it was the prime minister … he named it the national cabinet. I suggested we could meet more often during this crisis. I think it’s been fantastic.”

Party politics have been irrelevant and there have been no issues along party lines. “On national cabinet there are five Labor and four Liberals but you really wouldn’t know it,” he says. “There are no votes. There’s no lobbying. I find myself often very much aligned with (Labor’s) Mark McGowan in Western Australia.”

Marshall argues national cabinet has been one of Australia’s best weapons against the virus.

“A lot of people are very critical of our federal system,” he says. “They say we’re overgoverned, we’ve got too many politicians; but the reality is we ended up with nine sets of eyes on the national cabinet; and nine separate health ministers; and nine people on the AHPPC (Australian Health Protection Principal Committee).

“And nine is a really interesting number, because you will have outliers … and the outliers can sometimes bring everyone up there, or you can go to the middle or end up in between. But you are looking at a good representation of all of the different ways to look at a problem.

“The fact we had nine leaders and nine sets of eyes looking at the problem actually got us to a point which really understood just how dangerous this was very quickly.”

It didn’t mean everyone did the same thing. SA has been an outlier on testing, at one stage running more tests per head. (One highlight Marshall nominates was when the state secured enough supplies of ‘reagent’ – the substances that reveal the presence of the virus – to allow the testing blitz it wanted to run.) SA also allowed meetings of 10 people, rather than a limit of two. And, on medical advice, it didn’t close schools.

That was not a tough decision, he says, but given the abuse he got for keeping them open – “blood on your hands, Marshall” – he says it would have been easier “to capitulate and do it over a slower time”.

“But,” he says, thumping the table, “we were absolutely sure we were right – and if you are absolutely sure that you’re right you should back your convictions.”

Still, Marshall concedes that the AHPPC has not said state borders need to close, which SA did on March 22.

“Correct … but certainly we received advice from our chief public health officer that we should close our borders. It became very clear that we were getting increasing numbers of people coming back from interstate bringing the virus in. After we closed our international borders, that became the next highest source of new infections.”

Marshall suspects more than 10,000 people would have been in self-isolation in SA at one point, although no figures have been kept on that.

The biggest source of cases in SA were returning Ruby Princess passengers, two outbreaks in the Barossa Valley and the baggage handlers at Adelaide Airport which prompted 750 Qantas staff to be put in lockdown.

But by the time those cases arose, he says, he was confident a big boost in the number of people in the contact-tracing teams meant the state would be able to track down anyone potentially infected.

Now Marshall is in a tricky position, as business clamours for restrictions to be lifted. The risk is that a second wave could be triggered. He is desperate not to lose the “safe state” image he’s managed to earn.

“It was very easy to put the restrictions in place, it’s actually quite complicated to lift them,” he says. “We’ve got to get the balance right. We have formed the opinion we can ease the restrictions far quicker if we keep the state border in place and that means more people get back to work, more people get out of isolated environments, and overall we’ll benefit. But it means some people who really rely on interstate travel or work will be disadvantaged. There’s no easy way to go about this task.”

COVID-19 has also had a curious effect on politics, with partisan stoushes kept to a minimum and Marshall joining his fellow free-market proponent Scott Morrison in dishing out piles of cash to prop up business. So did the virus kill ideology? No, Marshall insists. The state and the individual have worked together in SA, he argues, which is “a very Liberal approach”.

Now, as the challenge moves more to the economy, all that will change. The gloves are already coming off as the argument embraces jobs and finances.

With an eye on that, Marshall has been interspersing meetings about COVID-19 with Zoom sessions spruiking SA to the world. He is convinced that the state’s handling of the crisis will attract people and businesses. “Adelaide’s always been one of the 10 most liveable cities in the world. It’s now the safest city in the world. That’s an incredible combination.”

People will increasingly see the benefits of working from home, and companies will have less desire to be in towering offices, he says. That brings opportunities because more online work means increased cybercrime. “We are simultaneously positioning ourselves as a leader in cyber security in SA,” Marshall says. “We’re just about to open the Australian Cyber Collaboration Centre (at Lot Fourteen) so I am, in between meetings on COVID, sitting down with companies like Splunk and CrowdStrike and Dtex, and encouraging them to move their offices to South Australia, the safest place in the world.”

Marshall says he will open the border. “I think it will happen progressively,” he says. “I’m sure we will be in a position to open up our state to some states or cities earlier than others. NSW, in particular, has performed extraordinarily well in recent weeks. Far better than even their own predictions.

“I think Australia will get there and probably get there much sooner than people think. The PM has said we want to be back to a COVID-safe environment in July – we haven’t put a date on it. And all state and territory ministers have signed up to that.”

This article is the final instalment in a special four-part SA Weekend series taking you inside South Australia’s response to COVID-19.