Red disaster: How China tariffs have smashed growers of our most important wines

Parts of our wine industry have been hit by the breakdown of trade relations with China, and “dumb politicians who like to ego trip and mess up badly by doing it”.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

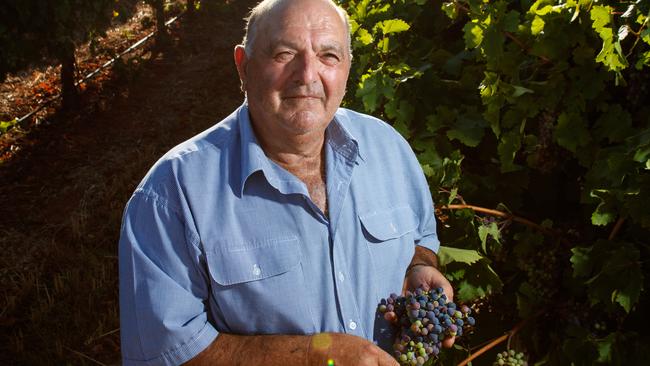

Jack Papageorgiou strolls slowly between the rows of cabernet on his Riverland property beneath a sullen sky. He inspects the clusters of fruit that will ripen, soon enough, from hard little peas into juice-laden wine grapes, looking for any signs of damage or disease.

It’s a familiar routine, one he has learnt in 50 years on this land.

But in all that time, he says, no season has been like this. One with so many challenges. So devoid of hope. Soul-destroying. A season to make him question his future in the industry.

Much of the surrounding region, of course, has spent the past months battling a slow-motion disaster with the inexorable rise of the Murray waters. But the flood that has rendered all Papageorgiou’s work and considerable financial input close to worthless is the one filling red wine tanks across the state at a time when they should have been long-emptied in preparation for the next vintage.

The bulk of this wine, in normal circumstances, would have been shipped to China, an export market that evaporated when its rulers slapped on a punitive tariff.

It’s a market that was always too good to be true, some in the industry argue.

Others point out that the weather, freight disruption, the economy, labour shortages and a change in drinking habits have contributed to this perfect storm.

All true.

Whatever the case, growers of shiraz and cabernet, by both value and reputation the state’s most important wines, are facing a disastrous year everywhere from the Riverland, to Langhorne Creek, to the Barossa.

How important are these varieties?

Based on last year’s vintage in SA, the pair represent close to half the total of wine grapes crushed, red and white. The only varietal that comes close to either of them is chardonnay.

As chief executive of the SA Wine Industry Association, Brian Smedley has seen some wild fluctuations in this business over many years.

He’s not given to overstatement or unnecessary hyperbole but concedes: “We haven’t seen the number of challenges facing the industry all at once like this before. They are more dramatic, more impactful in terms of operations and they will probably be a little more longer lasting.”

Roughly 60 per cent of SA’s wine production is exported and Smedley says the loss of China has been devastating for those who went “all in”.

“Many of us in the industry looked at China and thought ‘China is great, we will continue to plant for China’, not thinking there was a need to manage risk and look at other markets,” he says.

He argues it is likely that, without China, there is a “structural oversupply” of shiraz in the system and that the industry will need to consider whether some new plantings cease and existing vines are swapped to a new variety.

“If you are a small grower and we have many of them in SA, it is very difficult,” he says.

“It might mean five years of low income and that may not be an option.”

Papageorgiou is one grower facing precisely this dilemma. It has him questioning his future on the land he has nurtured for the past 50 years.

“I turn 70 next month,” he says. “I need to sit down with my wife and decide how long I can keep going. What is the way forward? I’m hearing that with the current status of wine with reds we could be looking at a difficult situation for two or three years.

“There is no way we can survive that long.”

Papageorgiou reckons it costs him $400 in water, disease control and other resources to grow a tonne of grapes.

He doesn’t have a contract and, at the time of this interview, was being offered $100 a tonne for his shiraz and cabernet.

Other growers, who have contracts with corporate wine companies such as Accolade, are being paid to dump fruit on the ground.

“It’s a difficult decision for myself and many other growers,” Papageorgiou says.

“Whether to turn off the water and let the vines die. There is no way I and many other growers can put extra resources in because we will go into more debt. Some of us will have to make a decision at vintage or straight after.

“The winemakers need to tell us if they want us or not.”

But the news isn’t all bleak for the SA industry. Far from it. Depending on where you are, what you do and how you have managed your brand through Covid and China, you might be doing quite nicely.

Growers of white wine grapes in general are going great guns, even better if they have some fiano.

Among the reds, grenache is setting new records and growers of many alternative varieties can’t keep up with demand.

The people behind privately-owned wineries tend to have a natural glass half-full, rather than half-empty, mindset, and it’s no surprise to find this optimism reflected in their assessment of the current situation.

Many report that direct sales to online customers proved a godsend during Covid lockdowns and continue to boost the bottom line.

Others are back travelling overseas and making inroads into new export destinations.

McLaren Vale heavyweight d’Arenberg is a good example.

Chief winemaker and high-profile ambassador Chester Osborn can put a positive light on recent events, despite estimating that China had represented 11 per cent of business in volume, 20 per cent of dollar income and “probably 30 per cent of profit”.

“It was a bit of a slam, you could say. Then Covid came at the same time,” he reflects.

“And we had just put in some significant price increases on our wines.”

But with direct purchases online helping fill the gap and markets in more than 90 countries developing, he says overall sales for the winery have risen.

His thoughts are with those on the land.

“The poor growers are the big losers in what is happening right now,” he says.

“Grape prices are tumbling for shiraz and cabernet.

“But it is a two-speed economy. Every other variety is in demand.”

He reckons grenache is the highest priced grape in Australia and alternative varieties like nero d’avolo and montepulciano are in serious demand. There is also a shortage of

white wine grapes so chardonnay and sauvignon blanc prices are going up, and “fiano is going gangbusters”.

Up in the northern Barossa, Jack Scholz of The Willows Vineyard can see both sides of the equation. His family has been growing grapes since they came to the area fleeing religious persecution in 1845.

Then, in the mid-1980s, Jack’s father, Peter, started setting aside some of these grapes for their own wine and now roughly half the annual crop goes into the house label.

This division of the business, focused mostly on the domestic market with cellar door and online sales, remains quite strong, the younger Scholz says, with no exposure to China.

“But on the grape growing side there is no doubt as an industry we are heading into an oversupply situation and seeing downward pressure on grape prices,” he says.

“There are going to be a lot of SA grapes that don’t have a home this year. It will be worse for growers in warmer inland regions but people right across SA will be affected.”

And while growers’ incomes plummet, rising inflation means costs are skyrocketing, as they are for most other businesses.

“But the grape and wine industry has always been cyclical,” Scholz says.

“Dad is pretty level-headed. We have discussed this and it’s nothing he hasn’t seen before. We lean on our strengths … grow the best fruit we can, make the best wine, give people a good experience.”

Willows also benefits from strong, long-standing relationships as a supplier to Peter Lehmann and a few other wineries that Scholz says won’t be taking advantage of ructions in the market.

“We’re old school in that way,” he says.

“We live to think the relationship goes both ways and we look after each other in good times and bad.”

A hop, skip and jump away in Angaston, the head of winemaking at Yalumba, Louisa Rose, leads a much larger operation.

She is also pragmatic about the current state of affairs.

“There is always something happening on a global scale that can tip the balance,” she says.

“While China and Covid was a perfect storm in some cases, it’s not that different to what we have seen in the industry before.

“And we know that this is an industry that is good at pulling up its socks and evolving to continue to … keep our place as a leader in the world of wine.

“A couple of years before Chinese tariffs, trying to find extra red grapes was expensive and challenging.

“Now we are in a situation where whites are in demand and finding extras of those is difficult.

“It is a change in balance but it is pretty normal. Fashions do it. Economics do it. Brexit does it. We just need to keep working …”

Rose says there is still strong demand for premium fruit but “maybe not at the crazy prices for Barossa shiraz that perhaps needed to calm down”.

A trickle-down of higher graded fruit might also mean “the consumer can get some really good quality wines at affordable prices”, she says.

Taking an overview of the wider Hill-Smith Family holdings, she can see potential upside for labels such as Oxford Landing and Yalumba’s popular two-litre casks.

“When inflation and economic circumstances are making life tough, you often see people gravitate to those more entry level wines,” she says.

Rose is more concerned with longer-term, big-picture problems such as climate change.

“I don’t think Barossa shiraz will look like it’s from the Riverland in two years,” she says.

“But I am worried about the planet in 2050 and how people will be fed and have a balanced and happy society.”

More immediately, she is considering how Yalumba, with its long and proud history of making traditional Barossa reds, reacts to a shift in public sentiment towards wines that are lighter, brighter and more drinkable when young.

That’s a wave brothers Damon and Jono Koerner could see coming when it was barely a ripple in Australia – one that fit perfectly with the more European style of wine they liked to drink.

“We wanted to make good, honest, sound wine … wines that people want to drink and that go well with food. Wines that represent the place they are grown,” Damon says of the guiding ethos behind Koerner wines.

“That’s how most of the world operates. You could see it happening everywhere else so it makes sense that it would happen here.”

The brothers have lived around wine for all of their lives.

Parents Anthony and Christine planted vines in the Clare Valley nearly 50 years ago and continue to run the Gullyview property today.

When Damon and Jono started Koerner in 2014, they bought three tonnes of fruit from the family block and a few neighbours.

They have since added the Leko label, based in Lenswood and sourcing fruit from the Hills, and Brothers Koerner, for affordable, everyday drinking. All up, they now crush around 200 tonnes.

“Overall we are going pretty well,” Damon reports on the current position.

Like many wine businesses, Covid actually helped, with online sales more than making up for a drop in the restaurant trade.

“But I’ve noticed in the last few months, sales are a little slower. Maybe it’s interest rates, people being more careful with money. I think it will be an interesting 12 months,” he says.

“We’ve all had it pretty good for a while but we will see what happens now.”

Damon can see a scenario where the bigger wineries with an oversupply of red go to market with some labels at heavily discounted prices.

“We are in the $28 to $50 a bottle range and if people can go down to Dan Murphy and get a bottle for $15 that does a similar job … And maybe at a restaurant, instead of spending $80 or $90 on a bottle, they spend $50 … that’s the risk for us,” he says.

That cheap wine he is worried about is the bread and butter for Papageorgiou and other Riverland growers.

Papageorgiou does a rough calculation that, at $100 a tonne, the big wine companies are paying only 10c for the fruit in each standard 750ml bottle.

Clearly, this devaluation of wine grapes is not sustainable.

Many of these growers are small family businesses and Papageorgiou says they are considering either switching crops or leaving the land altogether.

“Why would you encourage a family member to take up an interest in a vineyard when you know in the next four or five years it is going to cost them to run it?” he says.

“I wouldn’t want sons or daughters to suffer in this way.”

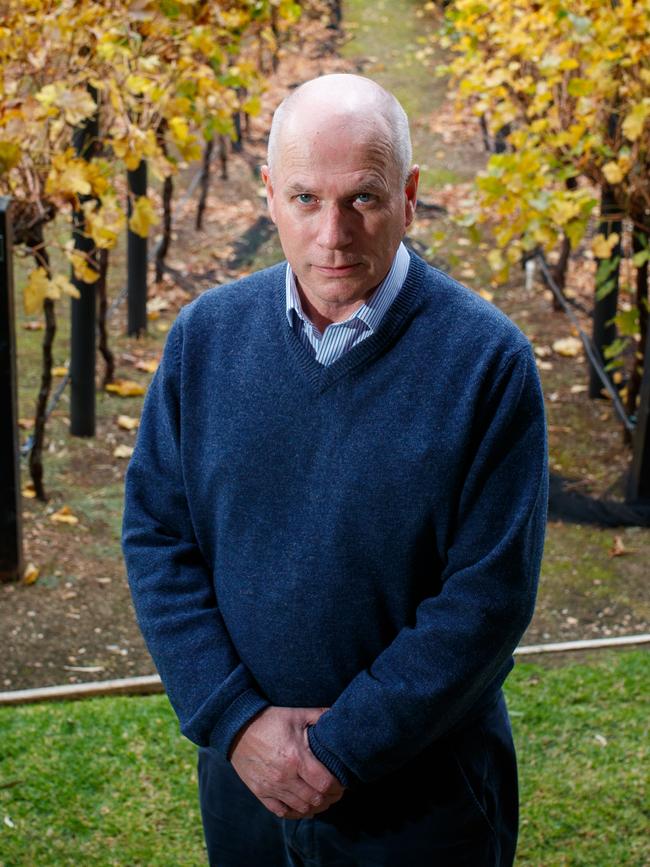

This is the sort of turmoil Jim Godden, chief executive of the CCW co-operative, is grappling with each day.

The CCW represents more than 500 Riverland growers who produce around 200,000 tonnes of fruit in an average year.

That’s an extraordinary 10-12 per cent of the entire Australian intake.

Godden confirms some growers are being offered as little as $100 a tonne for fruit and will be losing large amounts of money.

He agrees many will be considering their futures.

“If you are close to retiring or thinking of selling, in any downturn of an industry, people will review their business model,” he says.

Global giant Accolade, owner of brands including Hardys, Banrock Station and Grant Burge, is the CCW’s biggest customer.

Godden says the two organisations have been working on the oversupply issue since the middle of the year.

“It’s like any marriage,” he says. “Sometimes you want to revert to your corner and other times you have a good discussion.”

Accolade chief supply chain officer Derek Nicol says these consultations have resulted in a support package to assist growers in “one of the toughest years on record”.

The option discussed include “mothballing” a crop for this vintage; reducing yields by 15-20 per cent; or switching varietals from red to white to address strong global demand for varieties including sauvignon blanc and pinot grigio.

“This is not a situation growers or winemakers want to be in – but it is the reality,” he says. “We understand that many growers and their families are facing some hard decisions at this time and we remain committed to supporting them wherever we can.”

Papageorgiou believes the federal and state governments need to listen to growers and become involved.

“Leaving the industry on its own to find a solution is not the answer,” he says, adding that the promotion of Australian wine overseas needs to be more aggressive and more professional.

Osborn also wants to see more effort and funds put into marketing, particularly in the US where Australian wine has fallen off the radar.

As part of this, he advocates the return of the export marketing development grant to assist wineries taking their product around the world.

Osborn, always a big-picture thinker, calculates that the oversupply “lake” represents 5 per cent of all vines in Australia, an asset he values at $500m.

“If the government puts in $50m (to help marketing) I bet we would use all the lake up,” he says.

He is also hopeful about the return of the Chinese market if the rhetoric from government becomes more nuanced (and that was before the Chinese ambassador was photographed recently holding a glass of South Aussie red wine).

“We need to be very careful what we say about China and what they do,” he says.

“Unfortunately, there are some dumb politicians who like to ego trip and mess up badly by doing it. But really, you keep your friends close and your enemies closer. That’s what we need to do if we want to win.”

Scholz would like to see a reappraisal of the dealings between growers and the larger wine companies.

“Growers only know what they are going to be paid a few weeks from harvest,” he says.

“Most people still aren’t aware what they will be paid for parcels of fruit. It’s always been a hard one to wrap my head around.”

Brendan Carter, who with wife Laura is the founder/winemaker/distiller behind Unico Zelo, Applewood and Okar spirits, has a more forceful view on the big corporations and the “commoditisation” of Australian wine.

“If you plant what the market will take, and you plant a lot of it, the price of it naturally goes down,” he says.

“And the way you start to farm changes because you are not growing a quality crop … and we start riding a weird pendulum.

“We can grow cheap wine but we can’t grow it cheaper than China or Spain. We can’t compete long-term. It is such a marginal game.”

He urges both growers and winemakers to adopt a different thought process – one that begins with the land and, most controversially, without relying on irrigation.

“We always hear the line: ‘I craft wines I like to drink’,” he says.

“Maybe don’t do that but instead craft wines that the land can give you. It’s not weird shit for weird shit’s sake. It’s we’ve got a plot of land. This is how much rain lands on it. We need to plant a variety that needs just that water. All other decisions stem from that.”

He continues. “Irrigation has always been that great little tool we have to fit a square peg into a round hole. I’m not saying that shiraz is bad. I would just argue that we vastly overestimate the great sites we have when it comes to shiraz expressing that soil. We have shiraz where it shouldn’t be grown. That’s not saying you shouldn’t grow grapes there (on that site). It’s just not using 15 megalitres (of water) per hectare during a drought to craft commoditised wine. That’s the real war.”

The drinks made by Carter, who describes himself as “not a leftie … just a conscious capitalist”, are proof that his approach can work.

He is a proud ambassador for the Riverland but chooses varieties such as fiano (from Waikerie) and nero d’avolo (from Barmera) that “celebrate the soil” and can be grown sustainably.

He finds a use for fruit that might otherwise be wasted, such as in the award-winning Okar Tropic liqueur, made with gewurztraminer and Moscato giallo grapes that were bound for the scrap heap after a contract fell through, and leftover orange peels from Nippy’s juices.

Asked what one thing he would change if he could, and Carter returns to the theme of water.

“This is pretty extreme,” he begins, “but the number one thing government could do is make it illegal for people to irrigate vines.”

He uses the example of premium regions of France and Spain where growers need to ask permission to provide extra water and it is only allowed in extreme years.

“We need legislation that is helping us find more round pegs quickly. There is a lot money going into research … but it’s always shiraz and chardonnay because that is where the markets are – basically chipping off the edges of a square peg to get it rounder. But round pegs do exist. That’s a weird thing, isn’t it.”

Meanwhile Papageorgiou fretsabout what will happen to his crop of exactly those grapes. He says that local drinkers are one of the keys.

“I encourage people across SA … to consider buying a bottle of wine and that will help with promoting our wine and moving sales,” he says.

“Maybe consumers can do us a favour this year.” ■