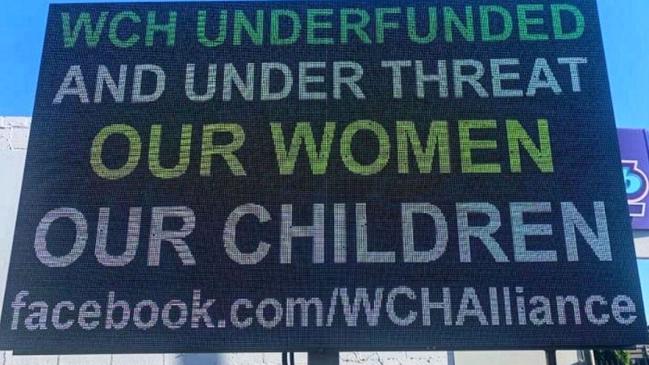

Overstretched Women’s and Children’s Hospital resources could mean a mother’s death in an emergency, doctors fear

Too few medical staff on duty at critical times have compromised safety at the WCH – and could lead to a mother dying in an emergency, doctors warn.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Women’s and Children’s Hospital has become so overstretched that a mother could die because of a lack of staff and resources, some doctors fear.

“I just feel like it’s getting to the point, particularly overnight, where it’s not safe,” one specialist told SAWeekend for an article on doctor stress.

“A maternal death is obviously horrific and an uncommon thing to occur, because we are a first-world country,” the doctor said of the WCH maternity section. “But do I think that could happen at the Women’s and Children’s? Yes I do.

“Because if you haven’t got enough staff, and the staff you’ve got have been flogged, they’re tired. And when you’re tired, your ability to make good decisions is to a degree inhibited.

“And I honestly think it won’t be until there’s a maternal death that’s preventable, or something really drastic that happens, that the executive will find more funding.”

The assessment was backed by Professor John Svigos, a prominent obstetrician, who said the WCH needed an extra $6m a year on top of its regular budget to make it safe.

He said the hospital had no maternal intensive care unit; outdated equipment including old ventilators; lacked proper surgical cover for women; lacked experienced midwives so that in a 12-bed ward, four senior midwives would monitor eight inexperienced; and had a neonatal nursery for the neediest newborns that operated at 110 per cent capacity.

“We’ve identified a whole pile of issues that could lead to a serious problem,” he said. “And we’ve been screaming out about it, but people are not taking any notice.

“And you know, sadly, that about the only time any notice is taken is when something bad happens.”

ONLINE NOW: SICK AND TIRED: Doctors lift the lid on a culture of bullying and stress in a broken health system. Story and podcast by Roy Eccleston.

The hospital has been the recent focus of criticism over long waits for emergency department care – including one case where a young girl’s appendix ruptured while she waited – as well as fears a new replacement hospital will not address current shortcomings.

It has also been experiencing stress in the maternity wards, which have been filled due to a COVID-19 baby boom, doctors say. While maximum staff are rostered during the day, at night it drops to three doctors for up to 90 people, they say.

A doctor who asked for anonymity said the possibility of a mother dying in an emergency was not an exaggeration.

The real danger would be if there were concurrent emergencies, with not enough resources to deal with both.

“There’s this huge disconnect between the reality of what’s needed and the executive making their decisions,” the doctor said of the under-resourcing.

WCH Health Network chief executive Lindsey Gough said parents should be assured they would always received the “best possible care” at the hospital, and insisted clinical staffing levels were always as agreed in enterprise agreements.

“At times, we do experience increased activity with more women than usual requiring our care, however escalation processes are in place to ensure we are able to maintain the same high standards,” she said.

Professor Svigos said there were a range of problems at the WCH, which he said delivered 4500 inpatients a year, including the most complex births.

Lack of medical staff was not only a problem overnight but at weekends where one consultant was “doing the work of three on a 12-hour shift”, he said.

Senior doctors had been unable to convince the hospital leadership “that there is this potential crisis”, he added.

“We’ve got morale issues related to working in a totally service-orientated under-resourced, underpaid, and underappreciated division. And that’s the result of an inadequate number of consultants to deal with the actual workload.”

TIRED DOCTORS, TOXIC CULTURE PUTTING PATIENT SAFETY AT RISK

Junior doctors in South Australia’s hospitals are suffering soaring stress levels that put patient safety at risk, according to a new survey by the AMA.

More than 80 per cent of junior medicos surveyed at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and the Flinders Medical Centre said they feared making a clinical error due to fatigue, while 73 per cent at the Lyell McEwin and 61 per cent at the Women’s and Children’s agreed.

These doctors in training also made up a large slice of the record number of medical practitioners who sought urgent mental health help from not-for-profit Doctors Health SA in 2020.

The newly-released AMA survey found levels of fatigue and bullying were generally higher than in 2019, despite a new focus on the issues within the health system.

Ninety-two per cent of respondents from the RAH worried about their personal safety due to fatigue, 80 per cent at the Lyell McEwin, 62 per cent at Flinders Medical Centre and 59 per cent at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

While the RAH was the worst place for bullying in a 2019 survey, last year Lyell McEwin was top with 64 per cent of respondents complaining, while RAH with 55 per cent and the WCH with 51 per cent followed. Flinders was the best with 33 per cent, one of the few examples where the levels fell (from 55 per cent in 2019).

Yet 80 per cent of Flinders respondents said they feared complaining would only lead to negative job consequences, slightly above the rate at the other big hospitals.

The issue of bullying and harassment has been a major issue, with a special summit run by the AMA early last year and the RAH in particular blamed for a toxic work culture.

State AMA president Dr Chris Moy said the higher figures were a result of continuing high workloads made worse by COVID-19 which meant fewer doctors could be brought from overseas or interstate, and exams for junior doctors were cancelled several times.

“It was a really shocking year for the junior doctors, they really handled it incredibly well. they’ve been untold heroes in this because they just kept on working.”

But he said bullying and fatigue remained a problem for the health system, leaving the junior doctors burned out and putting safety of patients at risk.

“The AMA understands that workloads and a bullying culture within the health system are causing incredible distress for doctors but also have a material safety risk for patients,” he said.

“Because they are so rushed they can’t see patients or get so tired they may potentially miss things.”

Some new measures, including moves to make hospital boards responsible for the health of their workers, have been made and should help, he said.

An SA Health spokesperson said there was zero tolerance for any actions that hurt the mental or physical health of staff including intimidation, sexual harassment, violent incidents or workplace bullying.

“SA Health recently committed to improve mental health in the workplace, with executive staff signing a Statement of Commitment,” a spokesperson said.

COVID-19 also made 2020 especially stressful for doctors in general, said Dr Roger Sexton, the medical director of Doctors Health SA which was set up to help troubled members of the medical profession.

Dr Sexton said the clinic treated 500 doctors last year, an increase of about 100 patients, or 25 per cent.

Those who called the 24-hour doctors emergency line, 8366 0250, doubled from 50 to 100. Doctors were anxious about issues like bringing the virus home to the family, and rapidly changing rules and protocols on the virus.

“Most of the calls were urgent,” Dr Sexton said. “They were doctors in immediate distress. Some were required to stop work for a time.”