Opera opens the flood gates at 2024 Adelaide Festival

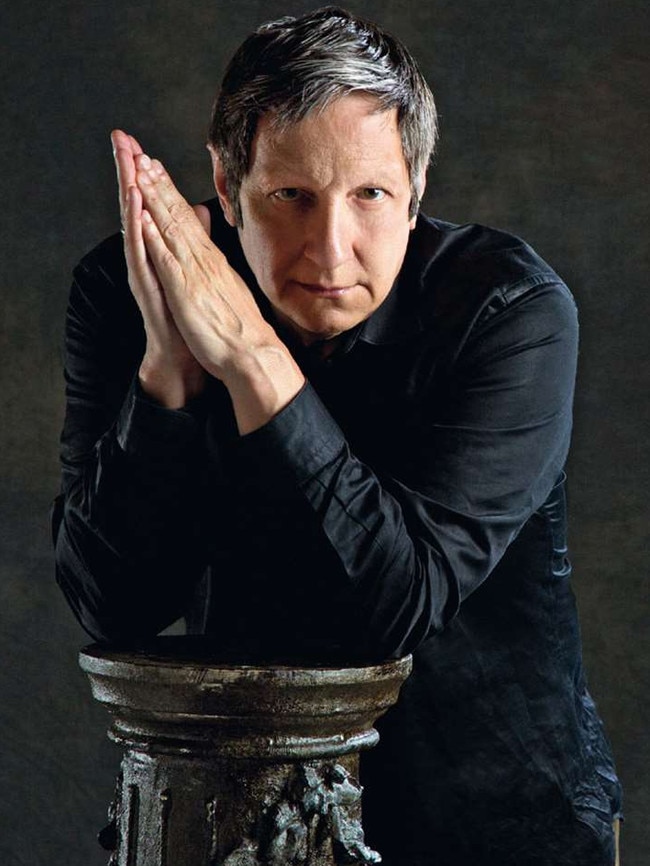

Meet Canadian artistic legend Robert Lepage, the man behind next year’s water puppet opera The Nightingale and a string of other Adelaide Festival hits.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Singers in wetsuits manipulate Vietnamese water puppets, boats and giant skeletons while wading chest-deep in a flooded orchestra pit.

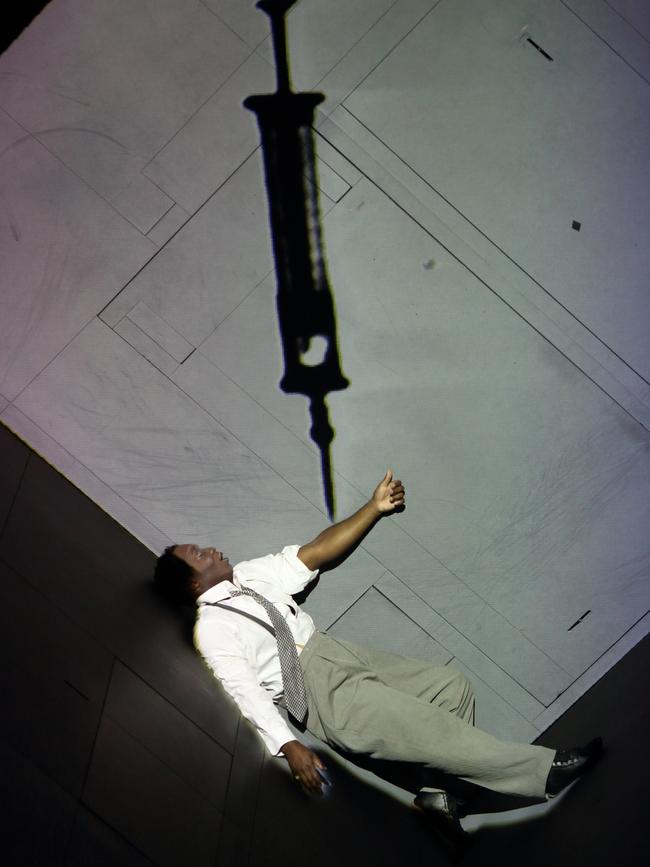

Chinese shadow plays are created behind a moon-like screen, bringing a fable’s fight between a fox and rooster to vivid life.

Choruses move miniature replicas of their characters in unison, while acrobats twist and tumble on stage.

To misquote Star Trek character Dr McCoy: It’s opera Jim, but not as we know it.

The Nightingale and Other Fables will be the centrepiece of next year’s Adelaide Festival program, set to the music of Russian composer Igor Stravinsky but transformed into a visual spectacular by Robert Lepage, founder and artistic director of Canadian company Ex Machina.

“It’s a very festive show … it has that open energy,” Lepage, 65, says from his office in Quebec City, where he sits surrounded by shelves which hold everything from classic Star Trek action figures to a replica Batmobile and a bust of William Shakespeare.

“Talk about diversity,” he laughs.

“The whole Star Trek series is based on The Tempest, you know, and a lot of popular culture is based on Shakespeare or the Greek myths that end up in the origins of theatre.”

Lepage was originally approached to come up with a concept by the Aix-en-Provence festival in France, which has partnered with the Adelaide Festival on past opera productions including The Golden Cockerel last year and Mozart’s Requiem in 2020. “When we were asked to do The Nightingale, we knew it would be a short evening of opera because it is about 50 minutes long,” Lepage says.

“So we wanted to do a Stravinsky evening and saw that we could if we gathered short fables, short stories that he wrote music for. There’s lullabies also that he wrote and there’s a very short opera that’s 15 minutes long called The Fox, which is often done before The Nightingale.

“They are all fairytales or fables and because of that there are a lot of animals … What do you do in opera when you have to play a fox or a nightingale, or a cat? So it was a good opportunity, or a good excuse, to use puppetry.”

Based on the story by Hans Christian Andersen, The Nightingale tells how the emperor of China receives a book from the emperor of Japan about the singing bird, which supposedly lives in his garden.

The Danish author built his tale on the naive European vision of Chinese culture in the 17th and 18th century, known as Chinoiserie, which Lepage took as the starting point to include a broad range of Asian puppetry styles.

“So we said why don’t we open the whole style? We went to Vietnam, we did our homework, we visited with the grand masters of Vietnamese water puppets,” Lepage says.

Other works in the program feature realistic Japanese Bunraku puppets, which are half life-size, Taiwanese hand puppets held by the opera chorus, Chinese shadow play and acrobats.

“Coming all from Asian cultures, it creates a very interesting evening, an homage to those styles,” Lepage says.

“If we were going to use water puppets, it meant we needed a basin. So we took the orchestra out … and put it on the stage, and filled the orchestra pit with water.”

Lepage says extraordinary things happened once the opera singers were asked to leave their traditional comfort zones, don wetsuits and operate the puppets while standing chest-deep in the specially designed pool.

“I thought this was going to be a catastrophe, that they were not going to do it … but actually, they are so involved because they are not preoccupied with their bodies. The body is this puppet outside of them.

“They are extraordinary puppeteers, they are very crafty. So that created a kind of liberating environment.

“The opera singer – who is usually very panicked about moving, about gesturing and being natural as they sing – to have them in wetsuits, in water, manipulating a fisherman in a boat and lending their voices to a small character, it freed them so much.”

From the moment they enter the theatre, audiences are enveloped in shimmering, reflected light from the water.

“Water is also an amazing conductive element for sound. The singers are closer to you, because they are in the orchestra pit and because they have all this water bouncing the voices. So it’s a very interesting musical experience, in that sense,” LePage says.

Ex Machina has a long history with the Adelaide Festival, performing its works The Seven Streams of the River Ota here in 1998, Needles and Opium in 2014, and The Far Side of the Moon in 2018.

However, LePage’s first work to appear at the Adelaide Festival was actually a decade earlier, at Thebarton Theatre in 1988, when he was still artistic director of fellow Quebec City company Theatre Repère. Some of his works there have since been absorbed into Ex Machina’s repertoire.

“The very first time we performed in Adelaide was the first time we travelled abroad actually, with The Dragon’s Trilogy. Our first experience in Australia was Adelaide … we had been to New York and then we had been to London, but that was about it. We had never travelled the world, really – our shows were very, very local at that time. Adelaide was like the big open door to the world, so that was brilliant.”

Ironically, despite the company’s multiple returns, Lepage himself has never actually been to Adelaide and will make his first visit here to direct The Nightingale and Other Fables.

“I never followed the shows because I was never performing in any of them,” he says.

Ex Machina has become noted for its inventiveness, particularly on a visual level, incorporating multimedia and technology on stage in new ways to create extraordinary spectacles.

Similar traits are found in fellow Montreal-based companies Cirque du Soleil and Moment Factory, which is again presenting works at this month’s Illuminate Adelaide festival.

“It’s a Quebec thing, it’s a French-Canadian thing,” Lepage says. “Because we speak French, because our theatrical work is in French, and our movies are in French, if you want to export your work, on top of the (spoken) language you have to find a visual language.

“A lot of dance theatre was coming out of Montreal at that time, a lot of very physical and visual theatre coming out of French-Canadian companies. I was part of that wave of artists who believe in the written word, but if we want to export what we do, we have to find a way to accompany what we are saying with another kind of visual or sound explanation.”

Opium and Needles featured actors performing in and around a giant mechanical cube, which rotated on one of its corners.

Another Ex Machina show. which was under consideration by the Adelaide Festival before the pandemic struck, was its version of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, which featured moving screens to focus attention on different parts of the action, and an actual sports car, which appeared to speed through streets in the rain on stage, an illusion created entirely by lights and projection.

As a child, Lepage was diagnosed with alopecia, which caused hair loss on his entire body, and he also struggled with depression in his teens as he came to terms with being gay. He found his calling studying at Quebec City’s Conservatoire d’Art Dramatique and in subsequent workshops at Alain Knapp’s theatre school in Paris.

Lepage says that in the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of “very interesting avant-garde theatre companies” were coming out of Europe, particularly Belgium and the Netherlands.

“They would be highly visual masters that created a kind of style and a vocabulary,” he says.

While he also became aware of the work of US experimental theatre director and playwright Robert Wilson and German dancer-choreographer Pina Bausch early on, Lepage says one of his primary personal influences was and remains US artist, composer, musician and film director Laurie Anderson.

Anderson – perhaps best known for her 1981 hit single O Superman, and who was married to the late rock icon Lou Reed – has also been part of past Adelaide Festivals and maintained connections to SA arts and education institutions.

“Very early on I was a great fan of Laurie Anderson, a great New York performance artist who you couldn’t really put in a jar,” Lepage says. “Was she a musician, was she a visual artist, was she a theatre storyteller? She played characters, she put on costumes, and of course she was very crafty in the way she used technology and integrated that into her poetry.

“I was very influenced by her in the early days.”

While Ex Machina continues to push what is possible visually and technically on stage, Lepage says it is “not a preoccupation”.

“I’ve always been interested in using any device that is on the market – even cheap devices – to try to squeeze out whatever stories or poetry it might contain, but I’m not a tech guy. I don’t know how to program anything.

“I’m surrounded, more and more, by a group of young whiz kids who know how to do these things,” Lepage says. “So I’m not obsessed by technology – I just happen to welcome it when it shows its face.”

Some of those “young whiz kids” have gone on to form companies of their own, such as Moment Factory, which is presenting two new works, Mirror Mirror and Resonate, in Adelaide this month.

Whereas arts companies in the US rely heavily on private benefactors, Canadian artists – like those in Australia – can also benefit from significant government funding to further their creative efforts.

“We have both federal government and the provincial government, and even the city governments, give money to us – of course, it’s nothing compared to (funding in) Europe,” Lepage says.

“We are well supported, because people really care for culture in Canada.”

Once artists from English-speaking Canada achieve a certain level of success, they often find new audiences in the US, Lepage says. However, French-speaking Canadian companies tend to have to take their works to Europe.

“Cirque du Soleil understood that it had to develop a type of entertainment that is universal, that has a resonance with everybody, without diluting the Quebec culture. They knew that if we want to evolve, we have to open up.”

Lepage says that Quebec City, where Ex Machina is based, is the oldest city in the US and Canada, dating back more than 400 years, but is still a “very young culture” compared to those in Europe. On the other hand, it is not “burdened” by tradition.

“Quebec sees itself as a culture to be defined, still,” he says. “We’re trying to solidify that and understand it, and that always leads to interesting and effervescent creative environments.”■