Latest reviews: Barbaros, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, At What Cost?

Read our reviews of Lina Limosani’s Barbaros, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, and State Theatre’s At What Cost?

Arts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Arts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Bárbaros

Space Theatre

June 28 to July 1

Never one to shy away from a challenge, independent choreographer Lina Limosani hits yet another jackpot with Bárbaros, a multidisciplinary project receiving its premiere in Adelaide as part of the Festival Centre’s 50th anniversary season.

Created in partnership with visual artist Thom Buchanan and ambient composer Sean Williams, Bárbaros is a sensory feast – even if much of the feast is full of grit and gristle.

Bárbaros, you see, are barbarians.

The set looms ominously in the dim light. There is a craggy peak, a shaft spearing skyward, and dark caves, at once enticing and frightening.

At the very beginning, the absorbing score from Sean Williams and James Oborn rumbling in the background, a monstrous figure emerges from high on the mountain, as if to claim dominion over the land.

But this is no benevolent ruler.

At ground level, a primitive being emerges, rapidly evolving the light, away from the stifling darkness.

Another even more primal figure emerges, in a kind of black amniotic sac. Their encounter is at once enticing and confronting, an opportunity to discover, or to fight for survival.

In another standout episode, the perspective shifts, and a vast, almost regal figure rises maternally over the land. But even she is not safe, and nature reacts, spear-like shafts (an echo of Garry Stewart’s Australian Dance Theatre here) slicing through with deadly effect.

The movement is utterly original. The three performers, Anton, Jana Castillo and Rowan Rossi, navigate the most complex, often interwoven movement with consummate skill. If not entirely new in the broader dance vocabulary, it represents a significant expansion of Limosani’s dance palette.

In this section, and throughout, the set is an equal partner. Designer Buchanan, best known these days for his canvases, is a sculptor of like distinction.

Bárbaros is captivating in every respect.

Peter Burdon

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Elder Hall

Junev 28

With conductor Graham Abbott in charge, you can guarantee things will zip along with plenty of energy. Piano soloist Daniel de Borah proved like-minded and consequently Mozart’s Piano Concerto in Bb K595 from 1791 received a pristine, light-footed performance with sonics beautifully illuminated.

Abbott and de Borah both treated the Concerto very much as a chamber work with a good deal of interplay between the scaled down ASO which was really on its toes and de Borah’s piano which sang with great finesse. Pathos was often present in de Borah’s elegant presentation and there was also brilliance in the concerto’s two cadenzas giving the sort of dramatic contrast Mozart lovers admire and expect. De Borah’s limpid tones in the deeply felt Larghetto middle movement proved an object lesson in subtle placement.

Haydn’s Oxford Symphony No 92 in G, also from 1791, completed this short matinee concert providing a chance to hear music by the two greatest composers in the classical style side by side.

The Oxford is one of Haydn’s finest symphonies and one was aware only perhaps of the more whimsical nature of Mozart’s creation compared with Haydn’s slightly more deliberate approach. That said the ASO shone throughout the expansive four-movement symphonic canvas.

With its two trumpets Haydn’s orchestral scoring is often brightly illuminated and the wonderfully high-spirited final Presto positively raced along with great élan. Joshua Oates’ soaring oboe lines elevated the gentle Adagio and the bustling opening Allegro involved plenty of very assured string playing.

Rodney Smith

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by Tarmo Peltokoski

Adelaide Town Hall

June 23

There are several reasons why this was one of the most interesting programs in the ASO’s 2023 season.

Firstly there was the Australian premiere of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s Ciel d’hiver (Winter Sky). Although it couldn’t have been known when it was programmed, the composer died just a few weeks ago.

She was among the most prominent and original composers of our times, but her music is rarely heard here.

One of the consequences of government funding priorities is that we hear a lot of contemporary Australian music – an admirable thing in itself – but a paucity of great music being created elsewhere.

Ciel d’hiver is both sombre and beautiful, a wonderfully engrossing and distinctive piece of music.

It led without a break into the 7th Symphony by fellow Finn, Jean Sibelius – programming that is no doubt connected with the conductor Tarmo Peltokoski, who is also Finnish and a rising young star among conductors.

And I mean young – he is 23 and possibly was the youngest person onstage. With fluid gestures and tremendous energy he roused the orchestra into exceptional performances of the Sibelius and Richard Strauss’s Don Juan.

By no means least on the program was a very fine performance of Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 1, with Li-Wei Qin as soloist.

Just one note was enough to confirm his mastery of the instrument – the first note of the slow movement, which grew from near inaudibility to a rich and beautiful tone with perfect control.

This was a performance full of character, from richly expressive to playful to dramatic. Ably supported by the ASO and its youthful conductor, Li-Wei Qin’s playing was an absolute delight.

Stephen Whittington

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street

Scott Theatre, University of Adelaide

Until June 25

Sweeney Todd is not everyone’s cup of tea, or rather, meat pie with sauce.

But put any distaste you may have aside, because Elder Conservatorium Music Theatre’s production of Stephen Sondheim’s musical thriller, directed by James Millar, is a cut above and not to be missed.

Before any of the wonderful cast even take to the stage, David Lampard’s ingenious set appears to be throbbing along to the sumptuous score played out under Martin Cheney’s marvellous musical direction.

And the set does take on a life of its own, as performers artfully deconstruct and reconstruct it, again and again during the performance, to transform it into the various locations.

The cast are equally brilliant. Matthew Geaney, in the lead role, is both haunted and haunting, and has the vocal chops, the intensity of his baritone escalating as Sweeney’s lust for revenge grows.

The barber’s scheming sidekick, pie maker Mrs Lovett, is deliciously devious thanks to Millicent Sarre’s magnificent character vocals and comedic timing.

Johanna and her suitor Anthony Hope are also captivating – Angelique Diko’s sweet soprano voice is like gossamer but can also soar to sensational heights, while Declan Feldhusen’s tenor has a tenderness that is beautifully befitting of his role as – like his intended – one of the innocents.

Space permitting, I would give each member of the cast a shout out – because every one of them inhabited their character to the nth degree – getting the perfect balance of light and shade necessary for what is an extremely dark comedy – and aided by creative lighting, costumes and make-up.

Lastly, in what many say is true evidence of a great show, audience members were raving about it – and Diko’s superb soprano voice – as they queued during interval, obviously eager for the second course.

Anna Vlach

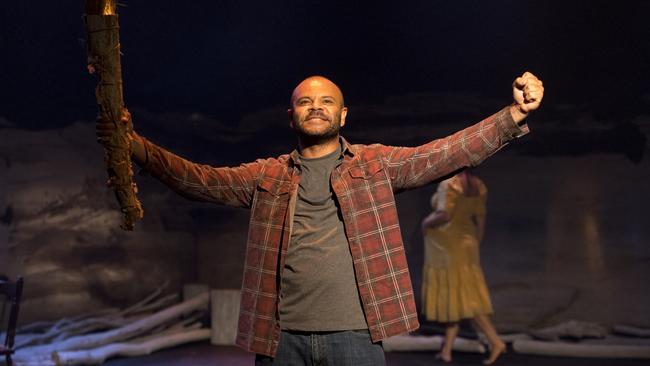

At What Cost?

Odeon Theatre, Norwood

Until July 1

This very week, the federal parliament has passed the Voice referendum bill by a comfortably large majority, but not without dissent.

And what of that dissent? How much is genuine, and how much is feigned, mere political posturing. And what of cultural safety?

Nathan Maynard’s At What Cost?, brilliantly directed by Isaac Drandic, is both timely and profoundly important.

We’re on Putalina country in Tasmania’s east, a key location in the recent history of Tasmania’s Aboriginal community. It was reclaimed by the community as recently as 1984 by Palawa from further north, the original population having been displaced and, tragically, exterminated.

Boyd is the next generation of those pioneers, alert to his responsibility for the land. With his pregnant wife Nala and young friend Daniel, theirs is a life of hits and misses. But they look forward to bringing new life into the world, on Country, as proud Aboriginal people.

The news that the remains of an ancestor, William Lanne – his body exhumed without sanction and decapitated, his head shipped off to a British museum – are to be returned and repatriated, with Boyd to have a key role, brings great joy.

Enter Gracie, a graduate student researching the man who committed this travesty – perchance the Premier, William Crowther, who was also a surgeon – whose interest may not be entirely benign.

She claims a bloodline that gives her rights. But she has no proof, and in Tasmania, until 2005, people had to prove their Aboriginality by a three-part test which included documentary evidence of their ancestry.

Is her word enough? Suffice it to say that for Boyd, it is not.

The performances are uniformly excellent. Luke Carroll is numbing as Boyd, one of the most wrenching and vivid performances imaginable. His emotional arc from relative peace to madness is as astounding as it is devastating. The comparison with Hamlet, skull included, is unavoidable, though Boyd is certainly not “mad in craft”.

Sandy Greenwood (Nala) and Ari Maza Long (Daniel) both tread a fine line between loyalty to their mob – in the towering personality of Boyd – and a willingness to listen.

Alex Malone plays the invidious character of Gracie with consummate skill, even as she causes, and seeks to cause, discontent and animosity to get her way.

There are no winners. There is nothing in this searing drama that sits comfortably. Nor should it. And at its climax, it is unforgettable. As it should be. That’s why At What Cost? is so necessary.

Peter Burdon

Australian Chamber Orchestra

Town Hall

June 20

Mozart’s Paris Symphony No 31 is dressed to impress in the 22-year-old composer’s effort to make a name in the French capital. Delicacies are scarce in this brittle, brilliant work with less heart and more pazazz.

Mozart’s sumptuous, persuasive melodies are replaced with short sharp motifs that hammer his message home. And the Australian Chamber Orchestra was up to the challenge with a taut, tight, tumultuous performance that knocked listeners’ socks off.

Bolstered by guest wind players and Australian National Academy of Music strings, the ACO ensemble was impressive and in truth the winds especially played divinely all evening.

Tuning and attack were as neat as a pin and added to the familiar ACO string sonics, playing in appropriately classical style directed by Richard Tognetti, the symphony positively zipped along.

A performance like this would have made Mozart’s name in Paris of the time, although alas in reality his visit didn’t go so well.

In the program’s first half Mozart’s later Haffner and Linz symphonies received equally energetic treatment from the ACO although Mozart litters them with memorable melodic lines and many moments of sheer delicacy that were embraced by Tognetti’s players.

The Haffner is the more straightforward of the two works and amidst the burnished tuttis of its opening Allegro and final Presto the beautiful Andante positively floated gently and joyfully.

A selection of numbers from Mozart’s Ballet music for his opera Idomeneo showed unequivocally how he can turn on even more drama when staginess is involved. The ACO relished it.

Rodney Smith

Ghosts, by Independent Theatre

Star Theatres

Until July 1

Sex outside of marriage, illegitimate children, a manipulative pastor, euthanasia … all grist to the theatrical mill. But imagine the reaction in 1881, when Ghosts was published.

Ibsen already had form for shocking, with A Doll’s House just a couple of years earlier skewering the notion that women should be subservient to their husbands.

In Ghosts, he drives a stake into the dark heart of the hypocrisy of the church.

Mrs Alving is a wealthy widow, very much in charge, investing her late husband’s fortune in the building of an orphanage. The local cleric, Pastor Manders, has come to finalise the paperwork. Is there no area of life in which the church will not intrude?

Her son Oswald has returned from his studies in art – there are fears that he may be living a dissolute life – and takes a shine to her maid, Regina.

Alas, the beautiful Regina, we soon find, is the illegitimate daughter of none other than the late Captain Alving.

There are wheels within wheels in this intense, intricately structured piece, which is deftly directed by Rob Croser. While Ibsen’s contempt for the institutional church is at the core, the journeys of each character are told in often stark relief.

Lyn Wilson is magnificent as the commanding Mrs Alving, straining every nerve to keep herself composed as her well-wrought plans begin to unravel.

And as the class-conscious, oppressive clergyman, Chris Duncan is a nightmare. The man’s sheer, unmitigated gall is breathtaking.

The prodigal son Oswald is keenly played by Eddie Sims, another arc that plays out at its own speed. David Roach plays the enigmatic Jacob to perfection, one time hectoring, another demanding, another persuasive, while Sophie Livingston-Pearce gives Regina a wide-eyed innocence, but not untinged with steel.

The setting, in the intimate Theatre 2 at Star Theatres, gives added intensity to Independent

Theatre’s stirring production. Ghosts challenges head on the church’s dubious influence as an arbiter of morality, and the very meaning of morality itself.

Peter Burdon

Australian String Quartet and Noriko Tadano

Waterside Workers Hall

June 16

I doubt that the Waterside Workers Hall in Port Adelaide has ever before resounded to sounds like this.

The hall is surprisingly pleasant with a relaxed atmosphere and deserves to be used more frequently for concerts. Its location near the docks at the Port may seem an unlikely place for a classical concert – classical music should get around more.

In any case, this was not the usual classical fare. The Australian String Quartet was joined by Noriko Tadano, a very capable player of the three-stringed Japanese shamisen – neither a lute nor a banjo, but one of the vast family of plucked string instruments found across the globe.

They each had their “solo” spots – if a quartet can have a solo. Highlights from the ASQ were two Essays by New York-based composer and violinist Caroline Shaw – who may be familiar to some people from her appearance in the series Mozart in the Jungle on a well-known streaming service.

These were complex and multistranded works, beautifully written for string quartet, and made for engrossing listening.

Noriko Tadano played a number of her own compositions, producing some striking sounds with her virtuosic approach to the shamisen. Her playing is exuberant and uninhibited, quite different to the restrained playing of a Kyoto maiko.

The vitality of her playing carried over into her collaboration with the ASQ in pieces arranged for shamisen and quartet by Emily Tulloch. The collaboration culminated in Vertigo, a frenetic piece with the energy of a rock/pop song.

Stephen Whittington

Garrick Ohlsson, piano

Adelaide Town Hall

June 8

If you are the kind of person who is impressed by pianistic gymnastics then you would probably find Garrick Ohlsson unexciting.

A veritable giant of a man, he looks capable of breaking the piano in half if he put his mind to it. Instead, he sits at the keyboard in a restrained fashion, doesn’t throw his arms about wildly or toss his head around looking for angels of inspiration on the ceiling.

He doesn’t mess with the music either; no extravagant rubato or desperate searching for an “original” interpretation. It’s easier to describe what he doesn’t do rather than what he does.

He seems to be focused entirely on the music, playing exactly what is written; it is precisely measured and perfectly balanced pianism. And that is what is so marvellous about it.

When he plays Debussy’s Clair de lune, a piece that nearly every pianist who has reached a modest level of competence attempts, he makes it seem so easy. But to play it with the exquisite control and subtlety, surrounding it with the most delicate aura through imaginative use of the pedal, is something only a master of the instrument can do.

On the other hand, the diabolically difficult fugue at the end of Samuel Barber’s Piano Sonata is obviously very demanding, but Ohlsson seemed unruffled while showing the tremendous power that he can effortlessly deliver without resorting to beating the piano into submission.

His program was unusual, including a new work by Australian Thomas Misson which owes a debt to Liszt, early, unfamiliar works by Chopin and Debussy’s Suite Bergamasque. Superb performances of the Barber Sonata and Chopin’s Scherzo in B flat minor were high points.

Stephen Whittington

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Sir Stephen Hough, piano

Adelaide Town Hall

June 3

The final two instalments of the cycle of Rachmaninov piano concertos offered richly rewarding musical experiences.

Central to it was the magnificent soloist, Stephen Hough, who – since his last appearance here – now rejoices in the title “Sir” in acknowledgment of his contribution to music.

With four concerts in 10 days it was also a mammoth undertaking by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra under the energetic direction of conductor Andrew Litton.

Episode 3 commenced with Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony, which is more interesting for the hints it contains about what Tchaikovsky would later become than for any intrinsic merits. The scherzo, at least, is a charming movement. Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto which, thanks to Shine has entered popular culture as the “Rach Three”, is surely the greatest of them in every respect, a peak which every aspiring concert pianist must scale.

Hough, whose ability to command vast numbers of notes is probably without equal, presented it as a work of epic scale, a vast musical narrative, War and Peace in sound. Untroubled by its complexities, he was free to present its drama and its intimate moments of reflection however he saw fit. At some points though the soloist and orchestra were slightly at odds.

Episode 4 included the rarely heard Fourth Concerto, a work that lacks some of the appeal of its predecessors but still has much to commend it. This performance was persuasive enough to make one think it deserves to be heard more often.

From the orchestra’s point view the high point of this concert was Rachmaninov’s Isle of the Dead, a sombre, lengthy tone poem which under the dynamic direction of Andrew Litton achieved impressive impact.

The series ended with the ever-popular Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. It’s hard to imagine a better performance. Hough’s scintillating playing had all the clarity and sparkle one could hope for, along with dry wit, lyricism, irony and a host pf other expressive nuances.

His partnership with the Adelaide Symphony and Andrew Litton was near perfect, and was an ideal conclusion to this splendid series of concerts.

Stephen Whittington

Australian Chamber Orchestra

UKARIA

June 3

As dusk crept across UKARIA’s backstage picture window, ACO’s seemingly disparate potpourri of short musical gems, entitled Wanderers of the Night took shape surprisingly well.

Their opening concert of three over the weekend proved once again how successfully they can surprise.

On this occasion they were joined by star soprano Cathy-Di Zhang whose four numbers with them helped to unify their bewilderingly wide-ranging program, from Merula and Arañés to Golijov by way of Strauss.

Her presence was absorbing, and her voice was flexible and multi-coloured enough to provide electrifying immediacy to Golijov’s Lúa Descolorida, which he wrote with Dawn Upshaw’s voice in mind. Golijov would have been delighted.

Moreover Zhang projected the spiritual quality of Merula’s Hor ch’è tempo di domire, and the folksy high spirits of Arañés’ Chacona: a la vida bona with equal ease and conviction.

Her intensity in Strauss’s Morgen!, always an emotional hotspot, was palpable and underscored general agreement she is a soprano to watch.

Further nocturnally inspired items from the ACO included Blood Moon and Reflections, two film scores by John Williams which both intrigued as they are early works with a more esoteric approach than we are used to.

Listeners seemed to relish the savagely modernist Reflections’ serrated sound bites, making one wonder how Williams might have developed more seriously.

Janácek’s Dobrou noc! (Good night) completed this eclectic yet eminently satisfying short program with barely audible sonic whispers from the expertly polished ACO players. They never fail to engage.

Rodney Smith

Adelaide Festival Centre

50th Anniversary Celebration Concert

Festival Theatre

June 2

Fifty years to the day since the Festival Theatre hosted its first concert, the crowds again surged into Adelaide’s home of the arts to celebrate the feast.

The great and good were there, of course, happily including many of the movers and shakers of the 1970s who brought into being such a wildly ambitious project, but also “we the people” in vast numbers.

After the obligatory speeches – half an hour of them, thankfully all excellent – it was on with the show, an entirely local cast that served as a reminder of the depth of talent we have in glorious Radelaide.

Duly Welcomed to Country – a couple of thousand people singing the infectious Niina Marni song – a fine new instrumental piece from bandleader Mark Simeon Ferguson, titled Dunstan’s Vision, underscored a wonderful photographic record of the building of the Festival Centre complex.

An Adelaide Oval-worthy cheer went up for host Libby O’Donovan with They Say It’s Your Birthday, backed by the “Dunstanettes” in pink shorts and long socks. (Google it if you don’t know).

The irresistible Latin beat of Lazaro Numa’s Valentina started the toes tapping, leading perfectly into Michael Griffiths’ You’re The Top (with cheekily localised lyrics).

The Grigoryans, Slava and Sharon, gave an affectionate, good-humoured performance of Mark Summer’s Julie-O, a charming duet that they’ve made very much their own, then Slava gave an enthralling account of Albéniz’s virtuosic Torre Mermeja.

Ngarrindjeri/Gunditjmara visual and performing artist Katie Aspel has soared in popularity since she dropped her first single a couple of years ago, and her songs are rich and rare. The poignant Here, with its aching lyrics written with her grandparents, “They took away your children … and did everything they could to take away our pride”, made for a time of solemn reflection.

Hyoshi in Counterpoint is a fascinating musical collaboration that blends eastern and western instruments in a compelling fusion, with a good-natured eastern take on a western classic for good measure.

The DreamBIG Children’s Festival Choir of 50 or more fine young voices lifted the spirits with Take Your Bow, then O’Donovan and the Dunstanettes joined the choir to lift the roof with Climb Every Mountain.

Inaugural Festival Centre director Anthony Steel, 90 years young, was cheered to the fly tower as he came on stage, relishing the story of the opening concert, 50 years before, when he sat Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in his seat after the interval then dashed backstage to join the chorus in the Beethoven 9th Symphony!

Finally, Happy Birthday, sparks and streamers, and out into the foyer where a carpet of cupcakes awaited.

Thanks to a bipartisan vision shared by Premiers Steele Hall and Don Dunstan, a field of dreams became a reality. They built it, and the people came. A million a year, these days. Here’s to 50 more … and a concert hall!

Peter Burdon

The Suicide

Red Phoenix

Holden Street Theatres

May 25 – June 3

A play that’s been banned and suppressed! What an enticement. Such was the fate of the Russian playwright Nikolai Erdman’s The Suicide, a withering satire on the plight of the poor and the lure of prestige that came at exactly the wrong time, in 1924.

A single line, “I find Marx boring,” gives a hint, and sure enough, the dictator Stalin, on his rise to power, banned the play, and exiled Erdman to Siberia for good measure.

It took 44 years for the play to receive its first production – in Sweden in 1968 – leading off a raft of performances.

In recent years, it’s proved a handy vehicle for new interpretations. Red Phoenix stick, bravely, to the original in Peter Tegel’s translation, the first in English.

Semyon Semyonovich is young and healthy, yet unemployed for a year and at his wit’s end. Suicide seems the only option.

Gripped by the news, the entire village seeks to profit from Semyon’s misery, trotting in one by one to make their cases, that his suicide note might plead their cause.

The day and time is set, a banquet arranged, the funeral arrangements too. Who will be the winner?

There are some standout performances in the 17-strong cast. In the lead, Joshua Coldwell is appealing as Semyon, at best naive (though likely plain stupid), as is Bobbie Viney as wife Maria, and Sharon Malujlo as his harridan of a mother-in-law Serafima.

Geoff Revell is great fun as the manipulative neighbour Alexander, and Kate Anolak is on top form as the crafty Margarita, fully applying herself to an affair with Alexander a week after his wife’s death.

Elsewhere in the village, special mentions to Nicole Rutty as the diva-like Kleopatra, and Michael Eustice as the intellectual Aristarch.

That said, The Suicide is hard work. Running just shy of three hours, it begs for editing, though it’s hard to see where director Brant Eustice could have started.

Perhaps that’s the reason its previous productions in Australia, and most of its international productions in recent years, have been heavy adaptations. Age shall, in this case, weary them.

Peter Burdon

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

May 27

Alongside a palette of golden tones pianist Sir Stephen Hough brings admirable objectivity to his performances and his reading of Rachmaninov’s ever popular Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor, which benefited hugely from these qualities.

Maintaining tight rhythmic control throughout and unleashing a plethora of superbly timed, stylistic and nuanced rubatos, he ensured the architectural qualities of this work were unmistakeable.

Up-tempo speeds and forward momentum kept the material, so often played sentimentally, free from all vestiges of emotional indulgence.

Yet it was a pity that some of these pianistic pearls were overwhelmed by the ASO’s spirited but forceful orchestral accompaniment, especially in the first movement.

Nevertheless, that doesn’t indicate any lack of attention or empathy from conductor Andrew Litton and indeed the interplay between piano and instrumental solo passages throughout was beautifully managed.

Hough’s encore, Chopin’s Eb Nocturne, proved a miracle of elegant simplicity.

After interval, Litton and the ASO produced as articulate and insightful an interpretation of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet Suite (arranged by Litton) as one could wish for, especially considering the well-known difficulties of a large orchestra in our smallish Town Hall.

From Dean Newcomb’s whispered clarinet sonics at the end of Masks to Andrew Penrose’s thunderous timpani in the Death of Tybalt, this remarkable score was brought alive by Litton’s superbly energised work from the rostrum.

Most noticeable was the ASO’s infectious enthusiasm for their task and obvious technical command. There was real panache in their riveting performance.

Rodney Smith

The Necks

UKARIA

May 27

The musicians of The Necks are masters at gradually unfolding musical ideas over an extended time frame.

Bassist Lloyd Swanton, drummer Tony Buck and pianist Chris Abrahams have been performing together as The Necks for 35 years.

This longevity has resulted in a distinctive style, and exceptional musical rapport. Known for their long-form improvisations, The Necks blend elements of jazz, minimalism and experimental sounds.

This was the group’s first performance at UKARIA, and the venue provided an excellent backdrop to the ambient nature of their music.

The first half of the concert featured minimalist motifs, with repeated chordal and arpeggiated patterns on the piano and textural sounds on the double bass subtly evolving over the hour.

The opening drum solo highlighted Buck’s innovative technique and deep understanding of percussive timbres.

The second set was somewhat more traditionally melodic, with blues-infused piano lines played by Abrahams with great sensitivity. Again, Buck created a beautiful palette of colours from the drum kit and Swanton used repetitive motifs to slowly increase the music’s intensity. The Necks has a finely honed sense of pacing, and the ability to draw out the musical material in a cohesive way, and the structure of both pieces in this performance was very effective.

Melanie Walters

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

Town Hall

May 24

The two stars of this concert, pianist Sir Stephen Hough and conductor Andrew Litton, each gave absolutely wholly of themselves in their respective items.

Sir Stephen Hough is a meticulous pianist with a big sound when required and, for all its shortcoming, Rachmaninov’s 1st Piano Concerto really took off under his fingers.

That said, Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece 5th Symphony, with Litton in control, proved an immersive experience in ways that the youthful Rachmaninov could only aspire to when he re-cast what was essentially a student work.

For all Hough’s pianistic persuasiveness and brilliance, and he has mountainous reserves of both, the music doesn’t engage and draw in listeners in the same way as Rachmaninov’s later concertos.

Nevertheless, Hough’s majestic cadenza in the first movement and electrifying prowess in the final Allegro were engrossing by themselves and there was tremendous determination in everything he did.

After interval Litton elicited a big-hearted performance of the Tchaikovsky from start to finish. He has that rare ability to know exactly where the significant nodal points of a movement lie and how to ensure the music drives forwards towards them.

In addition, there was pleasing precision and tonal depth from the ASO ensuring the fateful first movement, passionate Andante, lighthearted Waltz and tumultuous Finale all came across in spades.

Wind principals excelled with Adrian Uren giving a spacious performance of the Andante’s famous horn solo while clarinetist Dean Newcombe and bassoonist Mark Gaydon both shone throughout.

Rodney Smith

Australian String Quartet

Adelaide Town Hall

May 22

There are many reasons people go to concerts. I went to this one because Thomas Adès’ Arcadiana was on the program.

Others may have gone in spite of it – or because they know that the Australian String Quartet in its current incarnation is an exceptionally fine ensemble.

When keeping company with Mozart and Shostakovich, very little contemporary music is likely to pass muster.

But Arcadiana is an exception. It is an intricate and compelling work that unfolds in surprising ways. The end of this musical journey is far removed from the way it began, but seems absolutely right and is very moving.

It’s like staring into the distance at something you can’t quite make out – is it paradise, or just an illusion?

It is incredible that this quartet is nearly 30 years old – Adès wrote it in his early 20s – and that we have had to wait so long to hear it live. The ASQ gave a memorable account of this remarkable work.

Mozart’s D minor Quartet followed the Adès, although silence might have been more appropriate. If something had to come next, it might as well be Mozart, the incarnation of effortless beauty.

This is Mozart full of pathos, perfectly balancing anxiety and elegance, and beautifully played.

After interval came Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 9, a work of startling contrasts and dramatic power. The ASQ put everything they had into this performance, reaching a peak of intensity in the final movement, and bringing this splendid concert to a powerful conclusion.

But I left the hall with Arcadiana lingering in my mind.

Stephen Whittington

Silence

Blakdance

Odeon Theatre

May 19 and 20

Blakdance has been spearheading advocacy and innovation in First Nations dance for nearly 20 years, and among its many projects, Silence, from Karul Projects, is an important milestone for being the first commissioned by a major arts festival – Brisbane 2020.

Silence is the work of Karul co-founder Thomas E.S. Kelly. The work had its first development in 2018, a year after he’d won a Green Room award for [Mis]Conceive, which we saw in Adelaide in 2020.

I wrote of [Mis]Conceive that it was an elegant fusion of contemporary and indigenous music and dance, and that it didn’t shy away from the conceptions, or misconceptions, about the experience of First Nations people in Australia.

In Silence, Kelly maintains the rage. While there are hints of the good humour which pervades First Nations culture – an enterprising salesman hawks boomerangs, “real ochre, none of that plastic stuff” and “Bills”, a call from the “First Nations’ Tenancy Association” demanding payment of the rent – there is frustration, and there is rage, at the wilful ignorance of wider society, and in particular of political leaders.

The movement is a deft blend of contemporary and indigenous styles, with some really subtle

moments. At one point, a grounded circular movement takes on the quality of a balletic rond de jambe, and the leaps are uniformly graceful. At other times, cultural dance stands alone. Kelly’s own depiction of emu, grazing in the dust, is another highlight.

Raised fists are a repeated motif. They challenge, even shock, yet they fit, in the context of the movement and the meaning, and that is one of Kelly’s masterstrokes. Likewise the “Constitution” rap, with its cry “Nothing changes We’re still saying the same things.”

He’s alert to the ability of art to alter perception, and the audience goes willingly along the journey.

And what of the “silence”. The cultural astronomy some First Nations communities speaks of the Emu in the Sky, the bird defined not by stars, but by the absence – the silence – of light between them. As its shape changes in the course of the year, so does the relationship of the people with animals and resources on the land.

But there is also silence in the face of injustice, which is nothing short of complicity. We are

reminded in Silence (and this ought to ring in everyone’s ears) that Australia is the only

Commonwealth country not to have signed a treaty with its indigenous people. (Perhaps we were too busy watching the Coronation, that supreme emblem of our political system, on the other side of the world.)

Silence is driven along by the excellent score from Jhindu-Pedro Lawrie, a dynamic mix of

electronics, percussion and vocals. Altogether a powerful statement.

Peter Burdon

Sacred Sullivan

State Opera of SA / St Peter’s Cathedral

St Peter’s Cathedral

May 14

Few people realise that Sir Arthur Sullivan, of Gilbert and Sullivan fame, began his career as a church musician. He was a chorister at the Chapel Royal (those boys in fancy red tunics joining the choir of Westminster Abbey at the recent Coronation) and both his first and last publications were sacred music.

And so, as part of State Opera’s already wildly successful G & S Fest, and thanks to the company’s Music Director Anthony Hunt’s other job as Director of Music at St Peter’s Cathedral, we have Sacred Sullivan.

What we got was a selection of Sullivan’s church music set, very appropriately, within the context of Choral Evensong, a service which Sullivan would have sung daily in his chorister days.

The service was bookended by two anthems. First, “O gladsome light”, a chorus from the 1886 cantata The Golden Legend, a hugely popular piece in its day. It’s a really sensitive setting of Longfellow’s translation of an Ancient Greek hymn. More beautiful still was the closing “Calm be our rest tonight”, on a theme from the 1868 part song The Long Day Closes. A ravishing miniature.

Sullivan composed no music for Evensong proper — he is on the record as regretting his inability to do so — but Hunt confected a witty alternative. For the so-called “Preces and Responses”, two sets of petitions and responses sung by the choir, he arranged extracts from a vast array of the G & S operettas. To hear the familiar tunes of “With catlike tread” and “Hurrah for the Pirate King” in church is a memory that will linger long!

For the two Canticles, extracts from the Gospels sung at Evensong, one was a metrical text sung to one of Sullivan’s popular hymn tunes, the other a setting by Mendelssohn, whose influence on Sullivan cannot be overstated.

Speaking of hymns, no celebration of this kind would be complete without a rendition of “Onward, Christian soldiers” which was thunderously sung by the full cathedral (with a few wags singing some of the many parody lines). The famous melody also appears repeatedly in the Anthem at evensong, Sullivan’s last work, the Boer War Te Deum of 1900. The inclusion of such a popular theme could easily be a conceit, but this expansive setting shows Sullivan at the height of his powers, and was magnificently sung.

Kudos to the Cathedral for supporting this worthwhile venture. All praise to Anthony Hunt and the Cathedral Choir for their exceptional artistry — in a week where Hunt is also conducting the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra in SOSA’s The Pirates of Penzance — and to Cathedral Organist David Heah, whose mastery of the superb Cathedral organ (including an arrangement of “The Lost Chord”, and what might have been a cheeky reference to a certain Modern Major General!) made this a truly memorable occasion.

Peter Burdon

Schumann Quartett

UKARIA

May 13

The Schumann Quartett’s biography describes an ensemble for whom “anything is possible, because they have dispensed with certainties”.

But the only truly unexpected moment on Saturday evening resulted from a snapped violin string. The string quartet’s Australian premiere at UKARIA featured rather traditional repertoire, performed with beautiful phrasing and exceptional technical control, but taking few real artistic risks.

Mozart’s String Quartet No. 16 (K. 428) comes from a set of six quartets dedicated to Haydn. The highly chromatic first movement revealed excellent rapport and communication between the performers, with good balance and blending throughout.

Charles Ives’ String Quartet No. 1 ‘From the Salvation Army’ might be from a very different musical vernacular to the classical era, but it shared some of the lyricism and warmth of Mozart’s 16th quartet. Often considered to be Ives’ first large-scale mature composition, the work draws much of its melodic material from gospel hymns. The contrapuntal lines in the first movement were well-articulated in this performance.

The second half of the program featured Felix Mendelssohn’s fourth string quartet. In this work, the Schumann Quartett brought out the ever-changing emotions and characters to great effect, with excitingly nimble playing in the final movement.

The encore, the third movement of Haydn’s “The Bird” string quartet, was a nice call-back to the dedicatee of the opening work of the concert. The Schumann Quartett charmingly captured the playfulness and spontaneity of the bird calls in the middle of the movement.

Melanie Walters

HMS Pinafore

State Opera of South Australia

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Her Majesty’s Theatre

Seasons ends May 20

What a splendid evening of nautical delight, all shipshape and Adelaide fashion.

Her Majesty’s Ship Pinafore docks in Her Majesty’s Theatre, taking a break from pursuing the

Pirates of Penzance, but following them in repertoire.

Stuart Maunder’s clever direction takes full advantage of an uncluttered stage and a hard

working cast and crew. James Pratt is a skilful conductor of the Adelaide Symphony

Orchestra, accompanying the singers with perception.

Jeremy Kleeman’s promoted from Sergeant of Police to captain of the ship, and sings

superbly. Antoinette Halloran is again the woman who knows the truth, this time as Little

Buttercup the bumboat woman. Douglas McNicol, returns not as a Major General but the

disfigured and cunning Dick Deadeye. Ben Mingay staggers on, red faced, the traditions of

the navy incarnate, as a lightly camp Sir Joseph Porter KCB. It’s a delicious transformation

from his Pirate King.

Jessica Dean as the captain’s daughter Josephine is lively, loveable and her clear soprano

sound will touch your heart. She’s paired with Nicholas Jones as Ralph, pronounced Rafe.

He’s a voice to listen for, and, get in quick, he sails for France quite soon.

The sisters and the cousins and the aunts of the female chorus, wearing the elaborate hats so

suitable for the Ascot scene in My Fair Lady, join with the sailors of the crew in excellent

ensemble singing and the fine choreography. Fiona McArdle brings warmth to Cousin Hebe,

and James Moffatt and Andrew Crispe step forward confidently as mates. Their ensemble

work is a joy to behold.

It’s worth seeing twice, and listen out for some very clever tweaks to the libretto.

Ewart Shaw

The Pirates of Penzance

State Opera of South Australia

The Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Her Majesty’s Theatre

Season ends May 20

This enterprise of musical kind is an absolute joy, a real treasure. Pirates have struck gold.

If you want the receipt for a successful Gilbert and Sullivan production, you need first to trust

G and S to know what they’re doing. Stuart Maunder has taken that to heart. These pirates,

the land loving maidens and all, do the show proud. Gilbert’s gentle satire and carefully

managed confusions still make an audience laugh in 2023 as they did in 1879. Anthony Hunt

finds the touch of Wagner in the overture, and steers with a careful hand the Adelaide

Symphony Orchestra.

The cast is a heady blend of local favourites and visitors we now call our own. Ben Mingay

as expected is a swashbuckling Pirate King, and Antoinette Halloran turns in a really fine

maid-of-all-work Ruth. A maid-of-all-work herself, Halloran recently sang Brunnhilde in

The Bendigo Ring Cycle. John Longmuir sang heroically as Frederick and his second act

duet with the radiant Desiree Frahn, when they realise they must part, was one of the

highlights of the evening. Frahn is a delight.

Jeremy Kleeman, with his bunch of coppers, nearly stole the show and silver haired Douglas

McNicol, with kilt and matching accent, was the very model of a modern major general.

Nicholas Cannon as Sam, the pirate second in command, had a really colourful bunch of

reprobates on his side. The daughters, in crisp white, carrying parasols, were more than just a

chorus line. They all showed engaging flashes of character, lead by Cherie Boogart, Rachel

McCall and Jessica Mills.

The show included an adaptation of the Ruddigore patter trio, which seems now to be

customary, and which had the audience roaring with laughter. A few robes had been swiped

from Iolanthe, and there was an anachronistic fast food reference, but otherwise it’s a pure G

and S sparkling cocktail, or contraband sherry, if you prefer.

Ewart Shaw

Ascent

Sydney Dance Company

Dunstan Playhouse

May 11 to 13

Sydney Dance Company premiered it’s “Ascent” triple bill earlier this year, and now plays in Adelaide as part of a national tour.

A new work from SDC Artistic Director Rafael Bonachela begins the program. “I Am-ness” is classic Bonachela, lyrical and intimately tied to the music – Pēteris Vasks’ poignant Lonely Angel – with sophisticated contemporary movement delivered with neoclassical poise. Vasks’ music is, by the composer’s admission, inspired by a vision of an angel yearning over a suffering world.

Bonachela slowly, almost imperceptibly, draws together disparate strands of movement by the four dancers, until something approximating peace is attained. It’s a beautiful piece.

Next, a commission from European Marina Mascarell, a curious work with the even more curious title “The Shell, A Ghost, The Host & The Lyrebird”. It’s a technical tour de force, with the seven dancers manipulating ropes and pulleys that hoist sails and flag-like silks into the flies of the theatre.

These often give the piece an epic feel, as vast lengths of fabric flutter aloft. The interaction of the dancers with each other and with these props is impressive for its complexity, and the apparent ease with which it is accomplished. That said, the dancers are too often busy pulling and rigging, while the atmospheric score from Nick Wales does the heavy lifting.

Finally, a welcome revival of Antony Hamilton’s award-winning Forever and Ever, a wildly successful blend of top-notch choreography, a brilliant score, and sensational costume and lighting design. The piece starts with a long, long solo by Jesse Scales, which might be warming up, and over time becomes amusing, as if she’s just plain over it. A flash of light and the driving pulse of Julian Hamilton’s score begins, and we’re off on a wild ride.

The 16-strong company is onstage for practically the whole piece, much of it in large groups and long passages for the whole ensemble – tremendously exciting and fast-paced – and oh!, Paula Levis’s costumes. Dozens and dozens of them, the dancers shedding layers with practised ease, revealing another shape, another pattern, another colour – and often enough, another move.

It’s terrific. Ascent is a couple of hours very well spent.

Peter Burdon

Joh Hartog Productions

Ulster American

Holden Street Theatres

May 10 to 20

Belfast-born playwright David Ireland’s Ulster American is a comedy so dark, so ingeniously

offensive, and so fraught with emotional and moral peril, that it’s a miracle it ever saw the light of day. And indeed, when it had its Australian premiere in the 2019 Adelaide Festival, it divided the audiences in a way seldom seen, even for an adventurous Festival crowd.

A few years later, with an even greater understanding in the wider community about the scourge of sexual violence, it packs a mightier punch still.

Leigh (Scott Nell) is a successful stage director who’s scored a huge coup in securing Oscar-winning Jay (Brendan Cooney) to star in a new play by playwright Ruth (Cheryl Douglas). The banter between the two men, as they await Ruth’s arrival, is instantly confronting, with the brash American Jay’s misogynistic and demeaning language grating like nails on a blackboard.

Enter Ruth, at first starstruck and overawed, but not for long. She, too, can subvert the rules of the game to her own advantage, for ambition is not the sole province of the hyper-masculine star or the people-pleasing director.

Led by a devastating performance by Brendan Cooney, blissfully unaware that self-image comes from within, Joh Hartog’s production is a wild ride. As the director, Scott Nell pleases all, and consequently pleases none, while Cheryl Douglas is withering, and more than a little dangerous, as the increasingly tormented playwright.

Ireland dares, indeed demands, that the audience laugh – and you will shout with laughter – about an insidious problem. There’s no doubting that it’s fantastically uncomfortable at times, and sometimes it goes too far, but better that than for it to become acceptable.

It’s a salutary reminder that #MeToo is far from over.

Peter Burdon

Abbie Chatfield: The Trauma Dump Tour 2023

Thebarton Theatre

May 5

For the first time, I’m happy I’m not really out there in the dating scene, because if my favourite reality star has enough emotional relationship-driven trauma to fuel a national tour, who am I to even try.

That’s how I felt walking out of Abbie Chatfield’s one-woman show on Friday night.

The Bachelor star turned podcaster-radio-host-influencer-I’m-a-Celeb-winner-comedian-media-sensation – whatever she is – strutted out on stage at Adelaide’s Thebby Theatre and knew how to make the local audience happy.

“I’ve got a nice bottle of Barossa red,” she said, earning herself major brownie points as she sipped a Grenache throughout the evening.

Unlike her previous tour, the show didn’t bring out any special guest stars.

It was all Abbie unfiltered, and her tales of the trauma left by some very concerning partners.

It’s no secret that Chatfield has been rather unlucky in love.

Getting dumped on a rock in Africa in front of the whole country is a pretty unique experience, but the ex-Bachie star has had many more, never-before-told traumas that

would put any other girl off dating for good.

She took her audience through three of her most shocking relationships, spanning from her “2014 hospo Abbie” days in Brisbane through to the middle of Sydney’s Covid lockdown in 2020.

This girl truly is one of a kind, because if I’d been confronted with a man who wanted to show me his scalpel collection (you read that right) after the first night together, I would have run like Cathy Freeman.

But as Chatfield explained, while telling her fans a story that took them from roaring laughter to fighting back tears, her reaction to signs of abuse from partners is a lot different to her usual outgoing, bolshie, bubbly demeanour.

The star showed us a very different Abbie – a very raw, unedited version of the usual cheerfully loud feminist icon we know and love.

Talking to her audience from a pink couch, the show felt more like a wine night with a best friend than a celebrity tour.

We roared as she and an assistant read out scripts of a real-life conversation she’d had with an ex. We were enthralled with the tale of how she nearly became the wife of an heir to the

Australian “pumpkin dynasty”. We held back tears with her as she spoke about some incredibly messed up stuff.

We were both shocked and excited when she revealed she’s now in an “exclusive” relationship – of six days – with a new man.

In true It’s a Lot Pod style, we were treated to a live nightmare fuel segment where a member of the audience recalled her experience with a former lover she’d caught urinating on her clothing not once, but twice.

The thing about Abbie is it doesn’t matter who you are, what you look like or what you’re into. She feels like everybody’s best friend.

I think we all left feeling grateful we were able to spend a few hours with her on the couch talking about how crappy relationships can be.

Now to go home and delete the dating apps …

Isabel McMillan

Brink Productions and NinetyFive Theatre

Shore Break

Goodwood Institute

May 4 to 13

With a resume bristling with major theatre credits, Chris Pitman has a solid and well-deserved reputation as one of Australia’s finest actors. To that he now adds playwright, with his excellent one-hander Shore Break. For a first go, Shore Break is exhilaratingly successful.

A man is sitting on his deck chair on the beach. He can wander down for a surf, or simply sit and “be”. He talks about life and love, his and others, but he’s no armchair philosopher, for he speaks from lived experience, and from the heart.

There’s a distant father, a good man, but remote. A no-nonsense mother, loyal, tough-loving. A childhood and adolescence that’s detached, if not isolated. He flirts with the need to be something, someone, not always in the most sensible or admirable of ways. Likewise the need to be loved by another. A lifetime later, on the beach, with himself for company, he might have just found his calling.

Shore Break is authentic and genuine. Pitman and director Chelsea Griffith have crafted a really persuasive piece. And it’s not just the words, poetically rich and beautiful though they are. It’s the silence in between, one of the most difficult things in theatre. And so successful it is, that this audience member, for one, could have done with even more.

Shore Break is great new theatre.

Peter Burdon

Holden Street Theatre Company

Looped

Holden Street Theatres

May 2 – May 20

In its 20th year – many happy returns – Holden Street Theatres has founded its own resident company.

The first production is the Australian premiere of an absolute cracker, Looped, about a day in the life of the legendary Tallulah Bankhead.

The 2007 piece from American playwright Matthew Lombardo plays fast and loose with an actual recording session in 1965 in which the drugged and drunken star took a day to overdub – loop, in the trade – a single line from her last film.

With a prize-fighter the size of Bankhead to contend with, it takes a formidable talent to do justice to the role. Enter Martha Lott, unrecognisable in fur and sunglasses, and every inch the diva.

As she lurches on, drunkenly posing in the doorway, the audience bursts into applause -how else do you greet a star?

But there’s no time to waste. The dubbing is to be overseen by uptight film editor Danny, anxiously standing in for the director who’s literally fled overseas rather than spend another minute with the tempestuous Tallulah. He wants it done quickly: he’s got no chance.

Competing with (or more often, sustaining the blows from) such an outsized character requires a superior skill-set of its own, and Chris Asimos is up to the challenge.

If the play is inevitably a vehicle for many of Bankhead’s famous lines, most of them spectacularly vulgar, there’s a subplot that injects an element of drama into proceedings.

This explains Danny’s brittle temperament and sees just a little chink in Bankhead’s seemingly impenetrable armour.

Asimos is superb in a role that could easily be overdone, but is kept in check.

Director Peter Goërs has done a marvellous job. More, please.

Peter Burdon

Rocky Horror Show

Festival Theatre

19 April

Season to 13 May

Budget boas, distressed fishnets and strained suspenders abounded at the opening night of The Rocky Horror Show’s 50th anniversary tour. Suspiciously large bags suggested that more than a few props might have been smuggled in – and so it was, though mercifully neither rice nor toast were encountered.

The atmosphere was electric. The band kicked in – a mere five-strong, but sounding like Deep Purple – and the house roared. As the Usherette walked on for Science Fiction, the screams were deafening. The same for Brad and Janet, too.

Then it was the Narrator – and the place went nuts. For it was none other than Richard O’Brien himself – the show’s original creator, making a special appearance for just a couple of shows at the start of the run to celebrate its 50th birthday. Myf Warhurst took the lion’s share of the role.

And so it was on with the show. The cast in this run has some terrific talent. As Frank N Furter, three-time Olivier Award-winner David Bedella is a revelation, arguably the best voice we’ve heard in a role that’s often taken by headliners who get by on personality. He inhabits a role he knows inside-out.

The manic Riff Raff and his scheming sister Magenta are played with guts and gusto by Henry Rollo and Stellar Perry. Elsewhere in Frank N Furter’s realm, the buff, body-beautiful Rocky (Loredo Malcolm) could have read from the phone book and been a smash, but hey, he can sing too.

Our wide-eyed lovers Brad and Janet get the full apple pie treatment from Ethan Jones and Deirdre Khoo. Khoo, in particular, is one to watch, investing Janet with a surprising depth of character – not something you’d necessarily associate with Rocky Horror!

More than a few of the clued-up audience were eager to add to the fun, and Warhurst dealt deftly with the frequent interjections – most were daft, precisely three were funny – but that’s part of The Rocky Horror experience.

Hugh Durrant’s cheeky, colourful set has been given a few tweaks, and the whole production stands up.

Rocky Horror may not be the finest of theatrical wines, but it’s ageing (dis) gracefully well.

Peter Burdon

State Theatre

Every Brilliant Thing

Space Theatre

April 28 to May 13

Every Brilliant Thing by Duncan Macmillan and Jonny Donahoe is one of those shows that’s truly unforgettable.

A child begins a list of things that are just brilliant in an effort to cheer up his mother who, we know, has attempted suicide. An act of unfiltered love and light, oblivious to the darkness.

The narrator is Jimi Bani, who is instantly enrolled among the company of most loved Australian actors of all time. His performance, in this blissful account, is so warm and engaging that you cannot but be swept up in the emotion.

The list comes and goes. The first list was a few hundred items long. Mum got better, and it went into a box.

It is rediscovered, sadly, when she tries again, 10 years on. It begins to grow, now more intentionally. It again appears, many years later.

Depression is an illness that never truly goes away.

The masterstroke in the piece is audience participation. Dozens of those brilliant things are called out from the crowd. One person becomes a school counsellor, another dad, another Jimi’s first love.

Bani is deft in his handling of the volunteers – all of them willing, and you will be, too -coaxing and cajoling some wonderful ad lib moments.

But at the heart of it all is Jimi. His performance is so compelling, so affecting, so genuine, that you simply want to lift him up and carry him out in triumph. Which is precisely what the audience would have done, given half a chance. Instead, they clapped and roared.

As Jimi says, “Things might not always be brilliant, but they will get better.” Would that every life could be saved: perhaps not, but every life can be affirmed.

Peter Burdon

State Theatre

Prima Facie

Space Theatre

April 28 to May 13

From modest beginnings in 2019 in a 105-seater in Darlinghurst to the West End (and Olivier

Awards) and Broadway, Suzie Miller’s Prima Facie is a play that is truly taking the world by storm.

Part of the reason the piece has been so well received is its sheer timeliness – a play about sexual consent. Another is the currently small but rapidly growing company of extraordinary actors who give their all in the solo role of a career.

Tessa is a young defence barrister tipped for great things. She’s a defender – a lot of it defending men in sexual assault matters.

She’s adept at the game of the law, where legal truth – that which can be proved, and only that – reigns supreme. Until the night she is raped by a colleague, after which

the law’s role to provide justice is called, devastatingly, into question.

Caroline Craig is simply stupendous in the role. She owns the stage, and we are utterly captivated.

She rises and falls with the flow of Miller’s story. We get to know her, about her struggle-street upbringing, her selection by a top law school, and her pride in her achievements. Pride, yes, and some arrogance as well. And we feel her vulnerability, hidden from the rest of the world, only to be put to the test in the cruel arena called the courtroom.

Tessa’s long transition from swashbuckling victory to small, unsettled loneliness at the mercy of a merciless defender is superbly executed, in no small measure thanks to David Mealor’s astute and insightful direction. Nic Mollison’s lighting of Kathryn Sproul’s minimalist set is acute and effective.

Prima Facie is hectoring at times, but the importance of its last statements, about the need for

change, could not ring more loudly, or be more relevant. And Caroline Craig is sensational. The audience was on its collective feet before the lights went down. As well they might be.

Peter Burdon

GUTS Dance Central Australia

Value for Money

Odeon Theatre

April 28 and 29

Most dance companies have a dual function both as presenters of quality performances, and as

service to the wider community.

GUTS Dance Central Australia, based in Alice Springs, takes its responsibilities very seriously indeed, and alongside its vital work in providing opportunities for young people in school, on community, online and in detention, they’ve created some substantial dance works.

Value For Money is an intense, thought-provoking work that looks at value very broadly. Our value as individuals, and as community. The value of life itself. And less philosophically, the value of our work — paid or unpaid — in the world.

Beginning in dim light, a naked figure slowly awakens, first moving gently, then arching, perhaps in pain, perhaps in birth pangs. Certainly vulnerable. The figure is caught up in the arms of the other dancers, neutrally clad, and is almost magically clad: the movement is meticulous.

The first of several spoken sections decries the spoiling of the land — an act of devaluing something very precious. Glimpses of traditional movement are a reminder of the First Nations influence on the company and all its work.

Not all of the spoken word is entirely audible, something to address on tour.

The five-strong company all have their moments, and as at the beginning, the transition from solo to ensemble is consistently well executed.

In the long final section, again moved in dim light, and naked, the ensemble describe many

wonderful and intricate patterns in a kind of multiplication of the value they’ve been celebrating.

This last a full seven minutes, a very long stretch indeed, and one that would defeat many a

choreographer. Co-creators Sara Black and Jasmin Sheppard are to be congratulated on this very beautiful episode.

The sound design from Tom Snowdon is a winner, atmospheric and often captivating, and is integral to the success of the work.

Here’s hoping we see more of GUTS in Adelaide, and soon.

Peter Burdon

All About Eve

St Jude’s Brighton

April 20 to 29

St Jude’s Players kicks off its 75th season with an ambitious production of the 1950 Hollywood hit All About Eve. Or as history would have it, all about Bette Davis, whose performance, along with that of Anne Baxter, are the stuff of legend.

Margo Channing (Rebecca Kemp) is the unrivalled queen of the New York stage. She admits an enthusiastic fan, Eve Harrington (Leah Lowe) into her inner circle, only to find that Eve aspires to a crown of her own — and the talent to see it through. The machinations and manipulations of the rivals, and their circles of friends and foes, are the guiltiest of pleasures.

In the lead, Kemp and Lowe are excellent. Kemp’s Margo is haughty and imperious, with an acid tongue, while Lowe’s Eve is all sweetness and light — dangerously so. If Kemp is occasionally more Mae West than Bette Davis, it works.

Swirling around them is an enthusiastic crowd, by far the best of whom are Angela Short as Margo’s closest friend Karen Richards, and Joanne St Clair as the scheming drama critic Addison DeWitt.

Others in this secondary orbit are a mixed bag, and some of the characterisations are exaggerated: there’s only room for two stars in this sky.

The adaptation, by director Olivia Jane Parker, is faithful to the movie — perhaps too faithful, a blue pencil wouldn’t hurt. The set from Don Oakley is very cluttered, and a decorative nightmare, but makes good use of the tiny St Jude’s stage.

Peter Burdon

Sacred & Profane: Magnificence

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

St Peter’s Cathedral

March 13 and 14

A vast throng of eager fans headed towards St Peter’s Cathedral, where the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra was presenting Sacred and Profane, a concert featuring orchestral and organ music.

Unfortunately most them went straight past and into Adelaide Oval for the footy. Given that sport is our national religion, maybe these two events were not as dissimilar as it might appear. Those who did go into the cathedral were treated to an interesting and unusual program.

Under the direction of Anthony Hunt, the strings of the orchestra made very lovely sounds in Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis.

The placement of the instrumental groups might not have been ideal, but the enveloping texture of the music still created an effect that in today’s language would be called “immersive”.

Three Canzone by Gabrieli shone a light on the orchestra’s excellent brass section, but the opportunity to complement the spatialised instrumentation of Vaughan Williams with Gabrieli’s own spatialised Canzone was passed up.

Organist Joseph Nolan began Bach’s mighty Fantasia and Fugue in G minor in thunderous fashion.

The drama of the Fantasia and the irresistible momentum of the fugue created a monumental effect. It also made a nice segue to Poulenc’s Organ Concerto, the opening of which strongly recalls – or to put it less politely, is stolen from – the Bach.

This was a particularly entertaining performance of this riotous work which spans devotional music, via neo-Baroque, to tunes that would not be out of place in a cabaret.

Joseph Nolan was superb as the soloist, ably supported by the orchestra and in particular Sami Butler on timpani, whose role is almost that of a second soloist.

Stephen Whittington

Come From Away

Her Majesty’s Theatre

March 29 to April 29

The terrorist attacks on 9/11 are etched in history. All airspace in the US and Canada was closed, with planes ordered to land at the nearest possible airport. And so it came to pass that 38 planes, carrying 6579 people, found themselves in Gander, Newfoundland (population 9651) for goodness knows how long.

The Gander community met the challenge. In the course of a few days, lifelong friendships were formed.

The musical Come From Away, from Canadian duo Irene Sankoff and David Hein, is an affectionate tribute to this remarkable story.

And there’s much to like. The music and lyrics are beautifully crafted. The orchestration is ingenious, with exotica like the bodhran, bouzouki, Irish flute and even uillean pipes making for great atmosphere.

A crack band under the excellent Michael Tyack is on top form.

The dozen-strong cast is uniformly excellent, vocally and dramatically, each with a lead role, and plenty of others besides. The sheer number of characters, and the need for each of them to turn on a dime, means that timing is everything.

No-one missed a beat, for the entire 100 minutes of near non-stop action.

The production, directed by Christopher Ashley (who did the Broadway run), is tight as a drum. The set, from Beowulf Boritt, repays close inspection – it’s a fine work indeed, with a cleverly-used revolve – while the lighting design (Howell Binkley) is masterful.

Standout vocal numbers include the passionate I Am Here (Sarah Nairne) and Me And The Sky (Zoe Gertz as Beverley, representing Beverley Bass, the first woman captain for American Airlines, whose flight was among those diverted to Gander).

Come From Away is a heartwarming piece about a remote speck of light that came to shine brightly on America’s darkest day. A generation later, when nuclear-armed nations rise against others, and the signs of the times seem to be more about war than peace, it’s a tonic.

Peter Burdon

The Tempest

University of Adelaide Theatre Guild

Little Theatre

March 24 to April 1

The Tempest, the great play that many believe was Shakespeare’s swan song, is a balancing act par excellence. Part comedy, part tragedy, oppressive yet liberating, resentful yet forgiving.

It’s not the Bard’s easiest piece but the Theatre Guild’s production, directed by Bronwyn Palmer, has some fine moments.

By far the leader of the 15-strong pack is Jack Robins, whose towering performance as Prospero is a sheer delight.

Other standouts included Theodoros Papazis (Ferdinand) and a sensitive double act from Bronwyn Ruciak (Alonso) and Ann Portus (Gonzalo), and a wistful Ariel brought to life by Finty McBain (wearing a good allusion to the design theme, a glittering robe that turns out to be plastic).

There’s a lot of gender swapping, which works well enough, but requires keen revision, and more than a few slips got through, “The king my mother” being perhaps the most amusing.

There are some missteps, however, including a Miranda who’s more irritant than innocent, a vulgar, boganesque Trinculo and Stephano, and an overstated Caliban in the “crawling-around-making-grotesque-noises” mode.

It’s also far too long, and scenes like the Act IV masque could easily see the blue pencil.

Design-wise, torn fishing nets replete with plastic washed up on the shores of the Mediterranean island on which the play is set are a reminder of the fragility of what might otherwise pass for Paradise.

But it’s all worth it to hear Prospero’s great Act IV speech “The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, the solemn temples, the great globe itself – Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve …” They may dissolve, but the plastic won’t.

Peter Burdon

Australian Chamber Orchestra

with Joseph and James Tawadros

Adelaide Town Hall

March 21

East may be east, and west may be west, but the twain met more than 400 years ago in Venice.

That was the premise of this exhilarating concert by the Australian Chamber Orchestra and the Tawadros brothers.

Venice, in its heyday the greatest trading port in the Mediterranean, was the economic link between Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire and points further east.

Presenting Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, interspersed with music featuring the oud – or Arabic lute – and percussion, most of it by Joseph Tawadros, brought a new and fascinating perspective to one of the most familiar works in the classical repertoire.

James Tawadros, on a variety of hand percussion instruments, added another earthy rhythmic dimension to the dance-based movements.

This was like WOMADelaide with comfy seats, only better. It’s rare for collaborations between an orchestra and musicians from a different tradition to work as well as this.

The ACO is perhaps the most remarkable group of its kind in the world – it’s good to be reminded of how good they are – and possibly the only one that could pull this off.

They seem to be capable of anything, even keeping up with the extreme tempos of Joseph Tawadros, who sometimes takes off like a bat out of hell.

Joseph Tawadros and lead violin Richard Tognetti appeared to be dueting or duelling with one another at times.

The brilliance of the ACO and the brilliance of the Tawadros brothers make a dazzling combination. The result was a performance that was absolutely electrifying.

Stephen Whittington