Oh Boy: Did Culture Club really change Adelaide forever in 1984?

Few acts have entered the city’s folklore in quite the way this pop powerhouse did. But the myth may not match reality.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

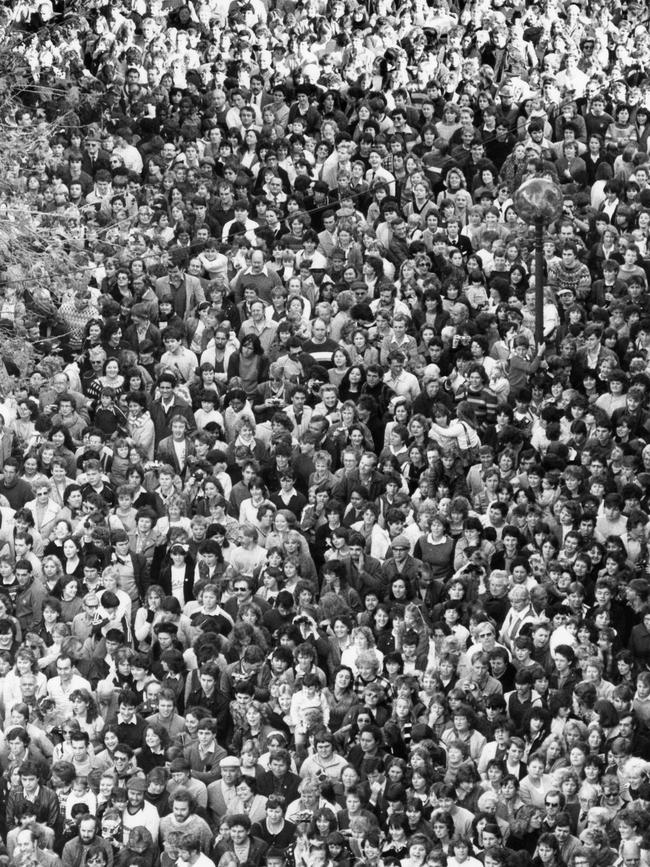

The streets of Adelaide are packed.

Packed with screaming teenagers and the odd bemused parent. They’re there to see a band, a band of four young English boys who are redefining pop music and setting the charts on fire.

No, it’s not 1964 and the band is not The Beatles. It’s 1984 and the band is Culture Club, a new-wave act blending reggae, Latin music, Motown and rock to create a unique sound.

And a unique aesthetic too, with an androgynous, gay, dress-wearing frontman in George “Boy George” O’Dowd, backed by a Jamaican-British bass player, an English guitarist and a Jewish drummer – a combination that delighted their young audience and drove conservatives a little crazy (early releases of single Do You Really Want to Hurt Me were reportedly wrapped in paper to shield US shoppers from O’Dowd’s gender-bending look).

In Australia, Culture Club were huge. Not Beatles huge, but perhaps bordering on Abba huge.

The band’s 1982 debut, Kissing To Be Clever, had piqued Australia’s interest with singles like I’ll Tumble 4 Ya and Do You Really Want To Hurt Me, but it was 1983’s Colour By Numbers with its huge hit Karma Chameleon, that took Culture Club to the next level.

And it was on the back of the worldwide adulation that Culture Club announced a world tour which included Australia.

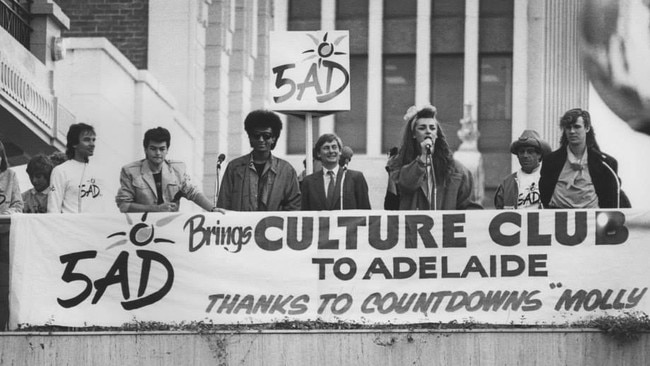

But it didn’t, much to the dismay of fans, include Adelaide. A petition, started by a disgruntled fan named Pennyanne Garner, was circulated, with 25,000 people signing it, and a radio campaign was launched on 5AD, backed by DJ Greg Clark.

The concert, of course, never happened because Adelaide simply didn’t have an indoor stadium capable of hosting an act of such magnitude at the time.

The city was, however, blessed with a whirlwind three-hour visit, which brings us back to those packed streets.

It was announced that Boy George and the band would make an appearance in Rundle Mall on July 5.

Organisers knew it would be popular, but nobody expected the numbers that turned out that day. Some news outlets reported 10,000. Others went as high as 25,000.

Whatever the real number, a quick look at the news clips which still exist on YouTube show a sea of humans, packed shoulder-to-shoulder on the Mall’s red bricks.

“Some people think there’s something wrong with you if you like dressing up and enjoying yourself,” Boy George told the assembled crowd.

“Well that’s bullshit, OK,” he added, before treating the throng to an a cappella version of Karma Chameleon, as close as Adelaideans would get to an actual concert.

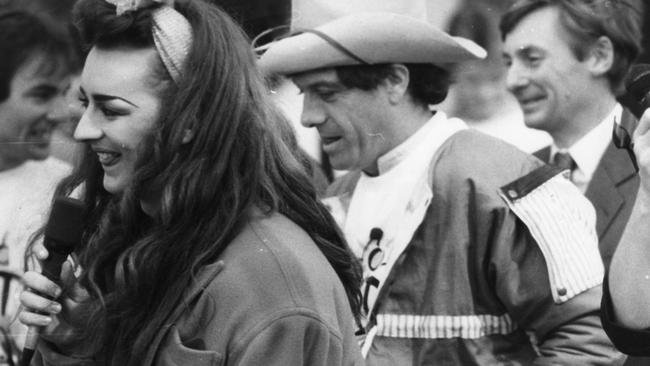

Speaking to News Corp in 2016, Molly Meldrum said he became involved in the campaign after sitting on a plane to Brisbane next to an Adelaide grandmother.

“She was telling me how her grandkids were so upset Culture Club weren’t going to Adelaide and how much they loved them and how popular they were in South Australia,” Meldrum said. “I mentioned it to their publicist for the tour, Patti Mostyn, and asked if she could talk them into going to Adelaide on their day off, just to make an appearance because people really wanted to see them. Then Patti called me and said, ‘They’re gonna go’ and I was in shock.”

Meldrum was there on the day, naturally, and so was then-premier John Bannon, who told the television news that the huge reaction to Culture Club was proof positive that Adelaide needed a purpose-built indoor stadium.

And in 1991 the Adelaide Entertainment Centre opened its doors.

What’s the truth about the Adelaide Entertainment Centre?

So was it Culture Club that was directly responsible for the Entertainment Centre, the very venue they’ll be playing in this month?

“Well I don’t know for sure, but I do like the story so let’s just say it’s true,” O’Dowd (Boy George) chuckles over the phone as he prepares to go on stage in the UK.

The 62-year-old sounds happy and healthy. His struggles over the years with addiction to heroin and other drugs – an addiction that led to an incident which led to serious assault charges and imprisonment in 2008, are well known.

O’Dowd, however, has been sober for the past 15 years, and he’s in – to use a hackneyed phrase – a very good place.

And he’s in a reflective mood, seemingly enjoying the chance to look back on those heady early days of Culture Club.

“Australia was one of the countries we were big in first,” O’Dowd says.

“I remember coming down there and stopping off in New Zealand and it felt like the longest journey I’ve ever been on.

“To arrive in Australia and have that crazy Beatlemania-type thing happen was just insane, and it got bigger and bigger everywhere we went. It was very exciting at the time. It was an adventure.”

Not that O’Dowd remembers all of it, describing the times as a whirlwind of flights and cars and screaming fans with very little downtime for reflection.

“I look at the levels of my consciousness now and what I see, and I see so much more than I used to,” he admits. “I used to be in these insane situations and I wasn’t really there; in these amazing adventures and I look at them now as though it’s a myth.”

Former premier Mike Rann, who was working for Bannon at the time, says while it certainly didn’t hurt the cause, the Mall appearance was perhaps not quite the overwhelming catalyst for change that many have since portrayed it to be.

There may be an element of truth to the myth, which has grown over the years, but there were certainly other factors at play.

“That (the push for the AEC) came quite a bit later during John’s second term when we started getting feedback from young people, campaigns by radio stations and lobbying by promoters that SA was missing out on big acts because the Apollo Stadium and Thebarton Theatre had insufficient capacity to make it commercially attractive for the big bands to come to SA,” Rann says from his second home in Italy.

“Adelaide Oval had been used sometimes in summer – for instance for Simon and Garfunkel in the early ’80s, and then the tennis stadium at Memorial Drive for the Rolling Stones in the early ’70s. But the problem was acts touring in the winter months. We needed an all weather stadium otherwise it was too great a risk for them to come to Adelaide.”

Rann does, however, recall Culture Club working its charm on the late premier.

“John Bannon liked and got on really well with Boy George,” he says.

“There was a massive reaction in Rundle Mall from the fans. John got a real buzz from it.”

O’Dowd also remembers that famous day in Rundle Mall. Well … kind of.

“I remember it from the pictures, and I’ve seen clips of it, so my recollection is vague,” he says.

“But I do remember at the time being amazed by how many people were there. There were escalators that went down into the mall and you could just see on both sides so many people.

“There were a lot of crazy things that happened on that trip to Australia. I was given the keys to Tasmania! I have no idea what that actually means, but it’s great.

“It was kind of hilarious to be so far away from home and getting this incredible reaction from the kids.”

That reaction was, to some extent at least, a reaction to the band’s image. It was hard to shock parents who’d grown up in the ’60s, they’d seen it all, but Culture Club were just outrageous enough to cause a ripple.

O’Dowd, particularly, with his feminine hairstyles, full makeup and long, flowing outfits upset the establishment, including clergyman and politician Reverend Fred Nile who warned that the youth of Australia would be corrupted by the very presence of the likes of Boy George.

The secret to Culture Club’s success

But image is nothing if it’s not backed up by the music, and Culture Club more than delivered on that front. The band’s first two records set the charts alight, yielding a brace of hits that became a soundtrack to the 1980s.

The music was catchy, well-crafted and empowering; mashing together the sounds that permeated the streets of London at the time.

O’Dowd says he often reflects on those early records, but is still no closer to really nailing exactly where they came from. Like many works of creative excellence, they seemed to emerge from the ether.

“I’ve looked at a lot of the early things that we did and thought ‘Where was my head at then?’,” he says. “What was my motivation? I don’t think you can ever know that fully. But yeah, I do look back. And I look forward. And I live in the present. I just get inspired by everything. Culture Club’s sound was so many different things thrown together in our unique London way. All that music we grew up listening to – punk rock, glam rock, soul music, reggae music … all of it went in there.”

The reggae roots run deep with Culture Club, with the Caribbean sounds from London’s huge West Indian diaspora having a massive influence on the band and O’Dowd personally.

“I remember hearing the reggae artist Johnny Nash on the radio in 1971, 1972,” he says.

“My older brother had Dandy Livingston, Liquidator, some of that early ska stuff. I’d hear that coming out of his bedroom.

“And it was a sound you heard everywhere around London, which has a big Jamaican population. I’ve always said that reggae doesn’t need me, but I need reggae.”

O’Dowd says the early days of Culture Club seemed like the perfect way to carry on the bohemian lifestyle he was carving out for himself in the clubs of early ’80s London, clubs where the rules of fashion and music were being rewritten.

“It all came out of punk rock, and punk rock was anti-establishment,” he says. “None of us were thinking about having careers, that seemed far too grown up. My friends were going off to college and art school, and I was the last little ragamuffin left of the heap. So I decided I would start a band.”

O’Dowd had what he describes as a “brief flirtation” with Bow Wow Wow, the band founded by Sex Pistols creator Malcolm McLaren in 1980, best known in Australia for the hit I Want Candy. “They brought me in for a while, then fired me without actually telling me,” he laughs.

“And Mikey (Craig, Culture Club bassist) saw my picture in the Melody Maker (magazine) and thought, ‘he looks interesting, I’m going to go and find him’.”

Finding O’Dowd wasn’t that easy though. The search was probably going to have to take place late at night in clubs guarded by big bouncers with strict “no squares” policies.

“Mikey found someone who could get him into this club called Planet where I was DJing,” O’Dowd says. “It was a really snotty club where you couldn’t get in unless you had, like, a lampshade on your head. Basically the opposite of the real world.”

Contracts were signed – after some initial hesitance from record labels worried that the flamboyant O’Dowd might be difficult to market – and the rest is pop history. “I was a hungry kid,” O’Dowd says. “I wanted to live in the bohemian world that Bowie lived in. That was what I was drawn to, and rock ’n’ roll music is a great gateway into that bohemian world.”

Did being gay matter at the time?

Having an openly queer frontman in a band at the top of the charts was revolutionary in a time when most gay singers chose to keep their sexuality a secret, often at the insistence of labels and management. O’Dowd acknowledges that his visibility was empowering for many young LGBTQI+ kids, but insists that setting an example wasn’t his main motivation.

“I think that at the time I was just doing what I wanted to do,” he says. “There wasn’t any sort of agenda. I wasn’t trying to effect change, except in my own life. I was trying to effect change in the areas of how my family dealt with who I was, how the world dealt with me, how fame dealt with me as a gay man.

“And all of that stuff was important, but not important enough for me to make a big deal out of it. I’m actually quite secretive; I don’t want everything out there. I like the sense of a rumour.”

Culture Club back in Adelaide

O’Dowd says he’s excited to be bringing the Culture Club tour back to Australia, a country he says feels like a second home for him.

The singer spent four years in Sydney as a judge on reality talent show The Voice, working alongside Delta Goodrem, Seal, Kelly Rowland, Joe Jonas and Guy Sebastian.

“What you remember about any place is the people – how you were treated, the sense of humour, the food,” O’Dowd says about Sydney.

“I painted a lot there, I did a lot of art that I went on to sell for huge sums, so thank you Australia.”

He says the band is sounding incredible, having recruited a bunch of new singers and musicians for the live shows including The Voice UK find Vangelis Polydorou who turned O’Dowd’s judge’s chair with a rendition of Culture Club’s Do You Really Want To Hurt Me. “We actually do a song together, and I tell the crowd about how he had the audacity to sing a Culture Club song,” O’Dowd laughs.

As for the possibility of a new record, the singer says the band has “a bunch of stuff we’ve written over the last few years” which may well find a home on an album in the near future. “There’s a chunk of really beautiful stuff, some dance stuff, a nice collection of things,” he says.

For now, though, Culture Club’s focus is firmly on delivering the best live show they can.

“Every night when you step on stage you learn something new about performing,” O’Dowd says. “You can always learn. And you gotta make them laugh as early as you can in a show. I’ve been doing this thing where I come out and say, ‘Hi, remember when I was the only freak in the world? Now they’re everywhere!’

“The crowd pisses themselves. I love it.”