John Hutchins suffers from the rare, cruel skin disease epidermolysis bullosa – and can’t be touched

The Pearl Jam frontman and his wife were stunned when a friend’s baby was born with a cruel, rare disease – and it spurred them into action. Now their fight has come to Adelaide.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Jill and Eddie Vedder first heard about Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB) when a close friend was born with the disease.

It was, they say, one of the most brutal conditions they had ever seen.

“Immediately after learning about EB my husband, Eddie, and I knew we could not turn away,” Jill Vedder says.

“We had to get involved and help in any way possible.

“Our family felt we could use our platform to raise awareness and funds and hopefully help find a cure.”

As lead singer of one of the biggest rock bands in the world, Pearl Jam, Eddie already had the profile and reach. Jill was also a well-known philanthropist and activist.

That was 2014 and together they co-founded the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Partnership

(EBRP), sparking a global movement to find a cure, which next Friday finds its way to Adelaide.

Jill Vedder says they are particularly impressed by the work being done at the University of South Australia’s Future Industries Institute, which is on the cusp of a world-first breakthrough that could transform the way EB is treated, having developed an antibody to attack the condition.

“The work being done at the University of South Australia has proven to be some of the most innovative research globally,” she says.

“Every year we vet each project we fund with our world renowned Scientific Advisory Board and the University of South Australia has repeatedly won grant awards and we are thrilled to know research is happening across the world and around the clock.

“We are honoured to have them as partners in the fight to treat and cure EB.”

EBRP has raised more than $50 million for EB research since being founded in 2014, and has helped fund more than 40 clinical trials. This year, it celebrated the first FDA approved treatment for EB in the US and also has an approved treatment in Europe.

The next step for the University of SA work is to progress it to human clinical trials.

Vedder says she is confident they can find a cure; the EBRP has a stated aim of finding one by 2030.

“We can cure EB,” she says simply.

“So, my family and the team at EB Research Partnership is dedicated, motivated, and committed to doing just that.

“Not necessarily because it’s easily achievable, but because these EB warriors deserve to have the world fighting for them.

“They deserve nothing less than a cure.”

Vedder said was inspired by the courage of those dealing with the condition every day.

“I’ve had the pleasure of meeting so many families over the years,” she said.

“Some of these families are currently battling EB every single day and some have lost loved ones.

“I am in complete awe of their bravery, strength and ability to stay positive.

“As a mother I can’t imagine the heartache these families go through.”

She finishes with a heartfelt message for those in Australia battling the disease.

“You are the most beautiful, strong, and inspiring people I have ever come across,” she says.

“Your bravery is what drives me and the team at EB Research Partnership.

“As long as you keep fighting, we’ll keep fighting.

“We won’t stop until there is a cure for every single person battling EB.”

The Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Partnership and Smart Cities Council are hosting The Future of Healthcare and Tech Summit on Friday at Lot Fourteen to raise awareness for EB. The following day, August 5, in conjunction with the Adelaide Football Club, they’re holding a Donation Game Day, where funds will be raised through a lunch and at the ground during the Crows v Suns game.

‘I’ve already skipped death twice’: The boy who can’t be hugged

Therese takes my hand and gently pinches a small piece of skin on the top of my wrist.

I barely feel it. She is a trained nurse, which can be seen by the deftness of her touch.

“If you did this to John, the skin would blister and fall off,” she says.

A moment later John enters the kitchen, where we are gathered around the big wooden table for lunch.

He is wearing short shorts and his legs and arms are wrapped in bandages. He says hello, grabs a plate, then quickly exits.

A group of shearers have gathered for the spread, stocking up for an afternoon of work on this sheep farm in Tarnma, a tick under half an hour north of Kapunda. They devour the feast of marinated chicken, potatoes and salad in minutes.

This sweeping rural property is home to Therese, Neville and John, and today is full of workers, not to mention their daughter Kendal and her two sprightly kids Lyla and Harriet.

Therese and Neville Busch have cared for John Hutchins since he was 17 months old.

He’s now 19 and they are his official guardians. He calls them mum and dad. His photo appears pride of place next to the couple’s six other kids on the wall of their living room.

John suffers from a cruel, painful and incredibly rare disease called epidermolysis bullosa (EB).

In basic terms, he’s been born without the glue that binds skin together. Any level of exertion can lead the skin to blister or break.

At this stage, there is no treatment or cure.

It affects about half a million people around the world and about 1000 in Australia, but the family don’t know of anyone else in South Australia with the condition, let alone anyone who suffers as badly as John.

He has the most severe kind, known as dystrophic, meaning he gets blisters and wounds all over his skin, but also on his internal organs, including the stomach, oesophagus, and bladder.

His particular condition is caused by an incredibly rare gene, the only one of its kind in the world.

The slightest bit of pressure means his skin will blister and fall off. Literally fall right off.

“I’ll show you what it means, this happened this morning. That’s my left knee,” he says, scrolling through pictures on his phone.

To the naked eye, they resemble third degree burns.

Neville chimes in that he can’t remember the last time John had skin on his back.

His fingers have joined together again through blisters, after surgery helped separate them. They resemble mitts. “These fingers used to be out, straight,” John says.

“He used to be able to do Lego,” Therese adds.

John continues: “But quite recently they’ve sealed over again. That’s mainly because I’ve been sick and in bed and haven’t been moving my hands much.”

That doesn’t, however, stop him being a whiz on the phone, as he scrolls freely and openly through photos which show images of what he has to deal with every day.

The phone, however, is important. It keeps him connected, and the phone, his loyal pooch Penny (a small, very friendly maltese shih tzu, who is light and he can handle with ease) and his tight-knit family are among the few things that make him feel like a normal 19-year-old.

It also helps keep him up and about despite the obvious physical challenges. He is super smart, quick-witted and cheeky.

Asked how he’s going he says dryly: “Getting there slowly.”

He’s also very bloody determined and, as Therese puts it, at times a little stubborn.

But the truth is the list of things he can’t do is long. He is unable to play any sport. He can’t be bumped. The condition has stopped him going through puberty. Swallowing is getting harder because his throat is ravaged with blisters. He can’t go out much. He can barely be touched (if he is, it has to be extremely gentle). He can’t be tickled. He can’t be hugged properly.

Professor Dedee Murrell, the director of dermatology at St George Hospital, Sydney, says in severe cases like John’s, this is caused by a missing membrane.

“And mummy gives you a hug and unfortunately just the hug wipes your skin off and causes the skin to shear underneath and produces fluid then, and a blister, and the fluid gets bigger and bigger, and then the blister ruptures and you have an ulcer left behind,” Murrell says.

This won’t stop John, though.

“Better if I do the hugging,” he says before leaning over the shoulders of Therese in a soft, warm embrace.

He’s been doing a lot more of that lately, she says a little later though tears, with a look that is both knowing and heartbreaking.

Therese and Neville are acutely aware that there are no easy answers, they just want people to understand what John is forced to confront and what they endure, every single day, as a family.

It’s not for sympathy. It’s not for a medal.

They’re a fair way beyond any of that. The more awareness that comes for a condition that baffles even the doctors at the RAH, the more funding that might follow. This might one day lead to an effective treatment or, dare they dream, a cure.

There might be other people out there they don’t know about with whom they can share their experience. Ultimately, they just want to get the message out. “We just want people to understand,” Neville says.

They’re not the only ones.

In the US, the condition has the backing of Pearl Jam frontman Eddie Vedder and his wife, Jill, who have co-founded the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Partnership (EBRP) and are running a global campaign to raise awareness and find a cure. Vedder refers to it as “the butterfly disease” because “their skin is said to be as fragile as a butterfly’s wings”.

In Australia, the EBRP has ambassadors such as Brisbane Lions champion Johnathan Brown, and is this week holding a conference in Adelaide, while the Crows are using the Round 21, August 5 game against the Suns to raise money for the condition.

This all helps to lift the spirits of John, Therese and Neville, but suffice to say, at this moment in time, they’re focused on just putting one foot in front of the other.

They are tired. They can’t remember the last time they had a break. They’d love to take John for a holiday, but would need to take a trailer full of bandages with them (they estimate they’ve gone through upwards of 60,000 of them so far).

Therese had to give up her job as a support office and library co-ordinator at a local primary school to care for him full-time. Neville battles a bad back from years working on the farm.

At some point, they could all use a bit of a break. At the moment, however, their cup is pretty much full.

John’s condition has deteriorated in recent months, which has resulted in severe seizures and more three-hour round trips to the RAH. At one point they had to call an ambulance.

More medication has resulted in more frequent mood swings, with anxiety causing his skin to break down.

“We are struggling. It’s getting worse,” Therese says simply, through tears.

Without a cure, John’s condition is terminal, but it’s not something they discuss too much.

“We just don’t know, it’s all very uncertain. That is hard,” Therese says.

Neville adds: “I guess it’s the old saying, every day is a good day when you’re above ground.”

What they do know is that they aren’t getting any younger. Neville is 66, and Therese 58, so they have had to call in help. Nurses now come three days a week to help with the bandaging and treatment.

Their day goes something like this. They start about 7am with a lot of medication ("about 20 tablets” by John’s estimation), then a bath with salt and QV lotion, then they start lancing and cutting the blisters with a needle. Then the bandaging starts. It can be a long day. Blisters can emerge all day. Some are as big as a tennis ball. A few nights earlier they’d been up at 2.30am applying more bandages.

Maybe it’s the country upbringing, or the years working on the farm, or something ingrained in their DNA, but this family is by no means throwing in the towel. Get up, roll up your sleeves, start again.

“You just do it. It’s bloody hard, but you’ve just got to get on with it,” Therese says.

John agrees.

“I’ve already skipped death twice in my life,” he says, referring to a number of earlier incidents, including a problem with his kidneys, and plans to do so again.

“Plus, what keeps me going is annoying my sister,” he says, pointing to Kendal across the room.

“You’re strong, you’re a gem,” Therese adds with a smile.

From here, they’re looking at a potential new powder treatment, which hasn’t been properly tested and is very expensive.

Ultimately, they’d just like a bit of hope.

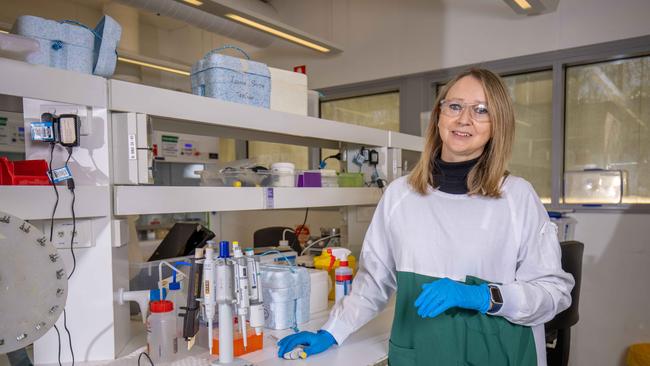

A bit over an hour down the highway towards Adelaide, Professor Allison Cowin is working out of her offices at the University of South Australia’s Mawson Lakes campus.

She tells the story of being at a conference about 15 years ago where a dermatologist was talking about a rare and particularly cruel disease. He was showing pictures of a baby’s bottom after the infant had its nappy removed. All the skin had been taken off its backside.

Her jaw dropped.

“I know as a young mum at the time, I thought that was just horrendous,” Cowin says now.

“And I just thought that there had to be something that I could do for those children.”

Cowin already had a strong background in the wound healing space (she is internationally renowned for her work on wound and tissue repair), but this was her first real exposure to EB.

And it triggered something deep inside.

She began to contact dermatologists in the field and started building up a research program. Her efforts kicked off slowly, picked up speed, and then began to snowball.

Now, more than 15 years later, Cowin, in her role as the acting director of the university’s Future Industries Institute, and her team of researchers and students are on the cusp of a world-first breakthrough that would transform the way EB is treated.

“Once I started I couldn’t stop. Now I just need to see it through,” she says.

They’ve identified a protein that’s present in wounds and blisters. It’s a protein that impairs healing. The more you have, the harder it is to heal.

And EB patients have a lot of it.

So her team has developed antibodies that come in and bind to the protein and stop it doing what it wants.

“And so by treating wounds with our antibody, it was able to eliminate that protein’s activity and then allow the wounds to heal better,” Cowin says.

They are now looking at the best ways to deliver the treatment for EB sufferers, with one option being a simple cream for surface issues.

For sufferers like John, where EB has taken hold internally, they are looking at injections which can treat multiple wounds at the same time.

“A child often has blisters all over the surface of their skin, so coming in with a dressing or some sort of treatment that just sort of sits on the top isn’t necessarily the most effective way to treat them,” she says.

“We thought if we could get the antibody into the circulation it would go to all of these different parts of the body and be able to start to heal that process; from the inside out is how we kind of coined it.

“And the other really remarkable thing that the antibody does is it also helps to improve blisters that occur inside.

“These children often have blisters in the intestinal tract, so they get a lot of IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) and it’s hard for them to swallow and this causes them to have nutritional impacts.

“So they often don’t eat very well and then they fail to thrive and then they get more prone to infection.

“So what we found was that the antibody was able to also treat those internal wounds as well.

“So it’s internal and external treatment simultaneously and that has never been done before.”

Cowin is quick to point out this would not represent a “cure” for EB.

It would, however, be a major global breakthrough in the way it is treated, would dramatically improve the quality of life of sufferers, and increase the lifespan of people with the most severe forms.

Preclinical trials are very promising and the team is hoping to move towards human trials in the not too distant future.

The biggest issue for sufferers right now is time.

Best case scenario would see the treatment hit the shelves in five years, but for this they will need funding. Lots of it. Likely upwards of $10m to see it through.

They obviously have the backing of the EBRP, but will need pharmaceutical companies to come on board.

“Pharmaceutical companies want to make sure that it’s going to work before they invest a significant amount of money,” she says.

“That’s where we’re currently at; we’re talking to people to show them what we’ve done.”

The other challenge is that EB is so rare that it impacts a relatively small group of people in Australia.

However, Cowin says the beauty of this antibody therapy is that it could be used to combat any number of diseases, from people with diabetes who suffer foot ulcers, to elderly people who suffer venous leg ulcers and burns.

She just wants to get the word out, to get people interested and to get them on board.

John sits on his quad bikefor the photographer, a smile from ear to ear, the helmet resting on his lap, his bandaged hands on the handlebars.

This is his pride and joy, which he has lovingly helped restore over the past few years, with help from Nev and Ivor at Riverton High School.

He has asked we all give it a clean before the photos start, just to make sure the bright blue finish comes through properly and any dust is consigned to the floor of the work shed.

On good days, he can take it around the farm for a whirl.

It’s been a little while, so John is a touch disappointed when he can’t turn it over today to show us how it rolls.

Funny, sharp, determined as hell, and dry, John ultimately wants what any other 19 year old wants.

He wants to be able to ride his bike. He wants to be able to hang out with his school mates. He wants to be able to have a drink at the pub.

“I had a cruiser on my 18th, it went down OK,” he says, before showing a picture of a bright orange cocktail he had at another party. “That one was really nice.”

He wants to see his beloved Port Adelaide win another flag. Neville says it would mean the world to him if he could just drive a car.

He’d love to be able to use his obvious smarts and to hold down a job.

He wants to be around for his nieces.

“You need to say that I love them more than anything in the world,” he says.

For now, though, John, Therese and Neville aren’t thinking too far ahead.

They’ll wake up early tomorrow, bathe, lance the blisters, bandage the wounds, and get ready for another day. Whatever that might bring.

It’s a rare genetic disease that results in extremely fragile skin that can be damaged at the slightest touch. Because the skin is so delicate, painful blisters and wounds frequently form and those suffering from dystrophic EB – the most severe kind – experience blistering inside and out, in places such as the mouth, stomach, oesophagus, and bladder. There is no treatment or cure for the condition yet, with daily wound care, pain management and protective bandaging being the only options available to improve the quality of sufferers’ often short lives.

WHAT IS EBRP?

EB Research Partnership is dedicated to finding a cure for EB, and finding it quickly. Their bold plan is to find a cure for EB by 2030, a big part of which is their venture philanthropy model. In 2022, they funded projects in Australia, the US, France, Germany, India and the UK for every EB subtype. They include a diverse portfolio of approaches including curative therapies, gene therapies, spray-on skin, ocular treatments, stem cell therapies – the list goes on. They fund a mix of academic medical centres and universities (including University of South Australia), start-ups, and biotech and pharma companies. EBRP prioritises funding for projects that are either already in clinical trials or have a strong strategy to be in the hands of patients in the next one to three years.

WHAT’S IT LIKE FOR JOHN?

In a video produced for EBRP, Dermatology Professor Dedee Murrell says even hugs can hurt. “The hug wipes your skin off and causes the skin to shear underneath and produces fluid then, and a blister, and the fluid gets bigger and bigger, and then the blister ruptures and you have an ulcer left behind,” she says.