High hopes: Inside SA’s new (largely unknown) super industry

After decades of being black-listed by authorities, an ancient crop is being rediscovered, with positive results everywhere, from the farm, to the kitchen, to the building site – and beyond.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

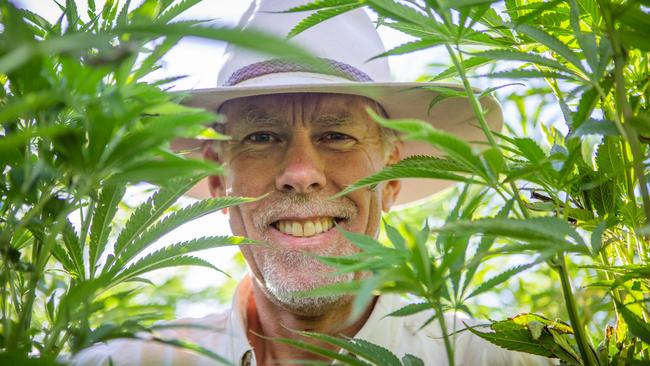

In the backblocks of the Coonawarra’s wine country, just beyond the regimented rows of vineyards, Steve Moulton stands admiring his new crop.

It’s a crop he and other farmers are convinced has vast untapped economic and environmental potential for the state – potential that has already been proven elsewhere in the world.

To the uninformed passer-by, however, seeing these tall, lush plants for the first time is likely to cause a different reaction.

Look at those serrated leaves! What is that smell? My goodness! Could it be ... a giant dope plantation?

And there lies the conundrum of industrial hemp, a commodity that by now could be/should be grown and used widely if it didn’t carry the stigma of other, more controversial, forms of cannabis.

For hemp’s growing band of advocates, it is a deeply frustrating story of long government intransigence in this country – and particularly this state – that has finally been addressed by a recent change to legislation.

They use terms such as “super crop” to describe a plant that is quick growing, not overly thirsty and, depending on the variety, can be used to produce everything from sustainable building materials to automotive parts, clothing, health food and medicines.

“It’s a pretty amazing crop when you think it can build your kitchen and fill your tummy as well,” says chef Karena Armstrong, who uses hemp seed and oil in her restaurant The Salopian Inn, as well as when feeding her family.

Armstrong is also the director of this year’s Tasting Australia festival, and will be part of a House of Hemp masterclass that is included in the program, and will include an express lunch of hemp-based food.

She is a serious advocate, describing the masterclass, designed by the University of Adelaide, as “something of a passion project”, and is keen to spread the gospel on what it means both in the kitchen and for the future of the state.

“Looking at new foods and new ways to eat and to cultivate, and to be producers, is key for South Australia as an economy being really successful,” Armstrong says.

“As climate changes and food needs change, we need to look at how we eat and use hemp.

“In South Australia there is this whole industry just waiting to happen.

“They’re growing it in areas that have perhaps seen a decline in other forms of traditional farming; some of it’s climate, some of it’s just the way the economy has gone.

“So there’s this real opportunity there, and that’s pretty cool.”

BREAKING DOWN THE STIGMA

The House of Hemp masterclass will also feature University of Adelaide plant scientist and hemp advocate Professor Rachel Burton, who points out the crop’s attributes are not a new discovery.

“We’ve grown hemp through history, for hundreds if not thousands of years,” she says. “It’s always been a useful plant.”

Burton lists examples including the decree from Henry VIII that farmers include hemp among their crops in the 1500s, and the historic hemp house in Nagano, Japan, still standing after 300-plus years.

Then, more recently, there is Henry Ford, who built an experimental car out of hemp fibre back in the 1930s.

But that is about the time this fledgling industry came to a grinding halt – in the US at least.

Strict new drug regulations prohibiting the cultivation of marijuana were deemed to apply to all forms of cannabis, whether they could get people high or not.

Other western countries followed this lead.

“There are lots of stories about why it was demonised to do with the competition it presented to other fibres, and that the alcohol officers (from the Prohibition era) ran out of things to do,” Burton says.

And while the laws around hemp have been changed in Europe and North America for a number of decades, things have progressed much more slowly in this part of the world.

Strangely, South Australia, for all its progressive reputation, was one of the last states to enact new legislation, in 2017.

To be fair, it’s easy to see why the prospect of widespread hemp growing might make an image-conscious government nervous.

“It looks exactly like a classic dope plant,” Burton says.

“You wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. If I put you into the middle of a field you couldn’t tell. They smell the same, they look the same.”

But appearances can be deceptive. Industrial hemp has been specially bred to contain minimal amounts (or none) of THC, the psychoactive compound that attracts users to marijuana. Smoke enough hemp and all it will do is make you feel ill.

Even with such reassurances, the rules around hemp are still far more onerous than other crops.

“You have to be fairly determined to grow this plant,” Burton says. “It’s not like growing wheat or barley. There are lots of bits of paper to fill out and push around.

“You have to get a licence and the sites are scrutinised. You can’t just bung it in any old place. They like it away from roads ... they don’t like people to be too close to it.”

And when the hemp crop is at its peak, just before harvest, it must be tested by agricultural officers. If the THC level breaches the magic 1 per cent mark and it is declared “hot”, it must be destroyed, and all the investment of time and money is wasted (though that is extremely rare and hasn’t happened in SA yet).

Armstrong says while there is naturally stigma associated with anything involving hemp, it is unfounded and needs to be challenged.

“It’s important that we think outside our normal thinking to navigate what’s happening in the world,” she says.

SOURCE OF GREAT FOOD

Despite these hurdles, a small-but-growing collection of farmers is taking on the challenge.

They can be split into two clusters.

One is based around the Riverland, where the stems of the hemp are processed for the building industry. The other is in the south east, where Mick Anderson and his company Good Country Hemp have developed a strong business using the seed to produce oil and other food and health lines.

Anderson says he first became interested in hemp 10 years ago, when he heard a radio story about the industry interstate.

“I thought it was unbelievable that hemp was still illegal to grow here when it has so many benefits and such a great future,” he says.

“That stuck in my head, and five years later the legislation changed.”

★★

Since then, it has been a steep learning curve for Anderson, who trained as an engineer. He travelled overseas to visit processing plants in France and Germany, and used this research to build his own facility in a shed in the industrial estate of Bordertown.

Then Anderson needed to find someone willing to take on the crop. “Farmers in general are pretty conservative,” he says.

“They want to look over the fence and see someone else growing something successfully before doing it themselves.

But we managed to find some farmers willing to stick their necks out.”

In the first year, results were disappointing and Anderson flew a consulting agronomist down from Queensland for advice.

While hemp is resilient once established, it does need to be treated well for a good yield. It also comes in hundreds of varieties that are suited to different regions and different temperatures, with the length of the day particularly critical.

“It is still a very wild and undomesticated plant,” Anderson says. “In a wheat and barley crop, every plant is identical ... but for hemp every plant is different.

“You get tall ones, short ones, skinny ones, fat ones.

“That presents a bit of a challenge ... but there is a lot of work going on with variety development.”

By the third harvest, in 2021, the initial return of 550kg of seed a hectare had more than doubled.

“Farmers began to see it could be quite profitable,” Anderson says.

“We were turning farmers away by year three.”

He started work on product development and marketing for Good Country, building an online presence and a network of retailers.

Anderson’s biggest seller is the oil extracted from the hemp seeds that, he says, have an ideal ratio of omega-3 and 6 fatty acids.

Working with a chef, he has released a range of salad dressings, as well as selling the hulled seeds, which have an appealing nutty taste and are good in baking and salads.

Chef Karena Armstrong was introduced to the Good Country seeds while judging the delicious. Produce Awards and started using them when baking bread and biscuits at home – even sprinkling them on her morning cereal.

“They’re like a cross between a nut and a sesame seed in terms of texture and I really like the flavour,” she says.

“Then I discovered the oil, and that was my undoing.”

Armstrong’s home kitchen experiments soon flowed over to the restaurant.

Salopian diners might be served sashimi sprinkled with the toasted seeds and finished with a hemp oil and citrus dressing.

For home cooks, she suggests drizzling a little of the oil over a roasted chicken.

On a personal level, Armstrong has seen first-hand the benefits.

“It has so much protein and we’re constantly looking at other ways of eating protein; they’re really easily digestible, the seeds are full of amino acids and they’re really quite delicious,” she says.

“The flavour is delicious. From a personal point of view, it has a real balancing effect on inflammation in the body.

“But, really, I just enjoy eating it. That’s one of the bigger things. Health foods are often thought of as a bit of a chore, that I might only eat it because it’s good for me, but that’s just not the case with hemp.

“The seeds are amazing; they walk the line of a nut and a seed.”

Armstrong says some of the Tasting Australia masterclass will feature “fancy chef cooking” but others will be extremely simple and functional, from carp and hemp tacos to ice cream.

“Some of the recipes in there are really simple,” she says.

“The crackers I make with linseed and hemp are so easy; they’re just beautiful gluten-free crackers that cost you nothing to buy. So there’s something for everyone in the recipes.

“I also like to ask questions. Why aren’t we using hemp? Why aren’t we using carp? I like to be a bit of a disrupter.”

A WORLD OF OPPORTUNITY

Steve Moulton was one of Good Country’s first hemp growers – or guinea pigs, as he describes it. He has trialled many different crops on his property at Maaoupe, just west of Coonawarra, but this one has him particularly excited.

Hemp grows over the summer, making it an ideal rotational crop to sow after harvesting winter grains such as wheat or barley.

“You need to get it established like any crop through summer time, with hot windy days and insects,” he says.

“But, after that, you are laughing. It doesn’t need chemicals or herbicides. You just treat it with love, water and sunlight.”

Moulton has now shifted from raising hemp for its seeds to varieties more suited to producing the fibrous stems that are used to make building products. These plants can grow at an extraordinary rate – up to 4m tall in just four months.

So confident is he in the future of this crop that he has teamed with his brother Mick and a pair of other partners to form the company South Fibre, with plans to build their own processing facility in the area.

“It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario,” Moulton says of the fledgling industry.

“Is industry going to come to growers, or growers come to industry?”

By running their own plant, these farmers can remove the uncertainty.

To see how this might operate, the Moultons need look no further than the industrial zone of Monarto near Murray Bridge, where the state’s first hemp fibre plant is up and running.

The owner Vircura is a plant technology company with ties to the University of Adelaide and its research projects (Professor Rachel Burton is a consultant).

After being established in 2022, Vircura explored a range of options before deciding to focus on industrial hemp and going in search of growers.

The first harvest in 2023 came from properties in the south east but this year, in a bid to reduce the financial and environmental impact of long-distance transport, the crop is coming from a farm in the Murraylands and another near Renmark.

Vircura’s general manager of operations, Adam Djekic, explains that the hemp stem is separated into two parts.

The outer sheath is converted into a fluffy fibre used for insulation, mulch and weed matting, as well as two sawdust-like substances. (The longer fibres used for fabric come from a different plant variety).

The real value, however, lies in the inner core, or hurd, which is processed into something that looks like a balsa wood chip.

Light and strong, this is the key to building products such as hempcrete, created by mixing hurd with a lime-based binder and water to form a slurry that can be turned into pre-made panels or poured on site.

Djekic says Vircura has been inundated with orders and inquiries from across SA and the eastern states, including large government and commercial projects.

“Hemp meets a lot of the new six and seven-star environmental standards of new buildings,” he says.

“When it is grown, it sequesters a lot of carbon, locks it into the product and keeps it there, and even draws carbon from the atmosphere as it cures.”

Djekic says that, while Vircura has expanded from two employees to 10, it is still in a pilot stage and, as the industry develops, the company will require more investment.

The small enclave of seven homes that makes up Miller’s Corner eco village at Mount Barker is living proof of the way hemp buildings can look and perform.

The homes were built from hempcrete between 2019 and 2021 by a small band led by Graeme Parsons, with help from a few friends and other supporters. While they did have carpenters and other professional builders involved at various stage, Parsons says they were all learning on the run.

“Having said that, they have turned out magnificently, and people living there are very happy with them,” Parsons says. “Anyone who walks into these homes, falls in love with them straight away.”

The air trapped within the hurd helps the walls provide excellent insulation and the finished product also “breathes”, allowing the air within a room to be slowly refreshed.

And hempcrete doesn’t burn, making the properties fire resistant – critical for living in the Hills.

Citing the example of the historic Japanese home and others in Europe that are up to 50 years old, Parsons is confident in the future of the Miller’s Corner properties.

“There is no reason these buildings won’t be here in 100 years,” he says.

Parsons believes a greater uptake of hemp in domestic and commercial construction will require more skilled tradespeople who understand that it isn’t too different to using other materials, and enlightened councils who can make the approval process easier.

Moulton is certainly bullish.

Looking at the hemp experience overseas and even interstate, he can see the momentum for change.

“If you had asked me 10 years ago, I would have said society wasn’t quite ready for it,” he says.

“Now, the timing is right. Economically it will work well for us, and environmentally it works as well. It’s just a super crop. Industrial hemp is king, really.”

BIG BUSINESS IN FEEL-GOOD FABRICS

Luci Keats remembers the early days of her Port Adelaide business, True Hemp Culture, when misunderstandings about products in the shop were more common.

“People used to say ‘Can you smoke that?’ when they came in,” she laughs. “I suggested that they start with a pair of socks.”

Keats’ interest in all things hemp was sparked when, seeking alternatives to the steroid creams used to treat her young son’s eczema, she was advised by a naturopath to try hemp seed oil. When that worked, she began changing his clothing to natural hemp fabric.

“That is where our passion for hemp came from,” Keats says.

“We thought, let’s grab this little market and see if people like it, and they most certainly do.”

True Hemp Culture now sells clothing as well as food, health and skincare products, pet treats and homewares.

It’s an industry that Chris Martin, from Adelaide-based Hemp Clothing Australia, knows well. After deciding to switch his fashion and uniform business to natural fibre in 2015, he has faced huge demand from individual customers, businesses and schools in particular.

“It’s not rocket science,” he says of synthetic fabrics.

“If you put your kid in a plastic bag and send them to school, they are going to be hot, sweaty, uncomfortable, their learning is going to suffer.”

Martin’s company now sends clothing across Australia and New Zealand. “Hemp has been looked at as some hippie thing for so many years, and it takes people some time to realise that what we offer is a very professional service,” he says.