Glenelg Beach transformed to stage Baleen Moondjan opening the Adelaide Festival

The Adelaide Festival will launch outside the CBD for the first time in history next week, with a highly anticipated show to transform one of Adelaide’s most popular spots.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For the first time, Adelaide Festival will launch outside the city.

The venue is Glenelg Beach (Pathawilyangga) and the production is the ambitious Baleen Moondjan.

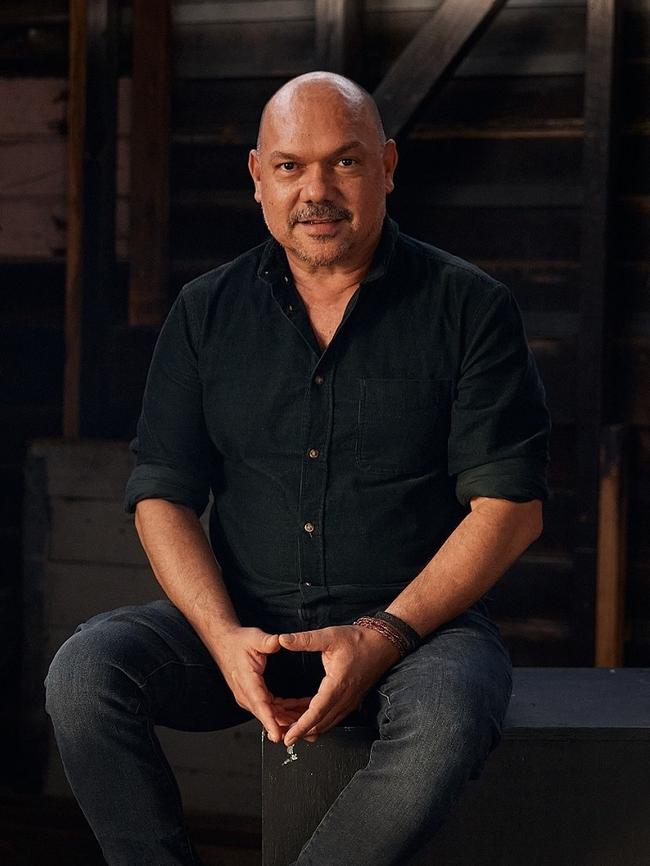

It is the vision of Stephen Page in his first major commission since leaving the world renowned Bangarra Dance Theatre.

It tells the story of a proud elder, a curious grandaughter and the day a baleen whale comes close to shore.

It will be told among giant whale bones on the sands of Glenelg.

In this in depth interview with SA Weekend, Page tells how he is attempting to build a bridge between old and new Australia.

Page is planning to have a word with the spirit tide. Just to make sure the ending to his new show has the perfect finale.

Page’s Baleen Moondjan is opening the festival and the setting is Glenelg Beach.

But the beach being the beach, there are all sorts of elements that could come into play, including weather and tide; not the sort of factors with which your normal dance production has to cope.

So Page is hoping for a little spiritual help to bring together all those dynamic elements and look after Baleen Moondjan and its audience.

“I haven’t talked to the spirit tide to say ‘hey, in the last 10 minutes, just come under everyone’s little legs. We’ll just push the tide up’.’’ Page says before laughing. “I wonder if I control wind and tide?’’

Baleen Moondjan is Page’s first major work since retiring from the legendary Bangarra Dance Theatre in 2022, which he directed for more than three decades.

Page says leaving behind Bangarra involved grieving but also promoted a new artistic freedom.

It’s also a response in some ways to last year’s referendum, when Australia rejected the chance to acknowledge Indigenous people in the Constitution and establish a Voice to parliament.

The pain of the rejection is clear in Page’s voice. He says the “massacre mentality’’ still exists in Australia. The emotion is raw. He worries about its impact on Indigenous elders. He rages against a process that saw Aboriginal people pitted against each other.

“They (the media) love watching that blackfellas throw spears at each other. And that, to me, is the sadness,’’ he says.

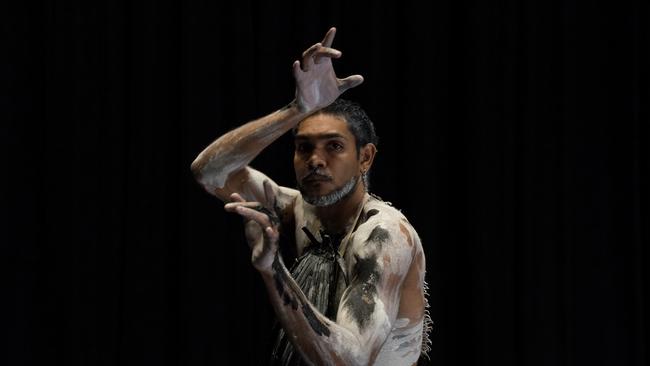

Page describes Baleen Moondjan as a “contemporary creation ceremony’’.

He also sees it as part of the healing process – Page believes art and the creative process are a medicine. It’s why he stayed with Bangarra after the deaths of his brothers Russell and David, who were also big parts of the dance company.

“The beautiful thing about telling stories like this, yes, it’s a creation story,” he says.

“Yes. It’s a totemic story. Yes, it’s generational about respect for knowledge of the past and for the future.”

In one sense, Page says Baleen Moondjan is a simple story.

But he hopes it can have a broader impact by bringing First Nations’ stories to a bigger audience, by building a stronger connection between the ancient culture of this continent and modern Australia.

“Seeing that, feeling that, connecting to that can just shift or implode your consciousness about First Nations existence, and who we are as just the humane aspect and the spirit aspect,’’ he says.

Baleen Moondjan will be performed among giant whale bones on a set designed by Page’s long-time collaborator Jacob Nash.

Inspired by a story from Page’s grandmother, who is from the Ngugi/Nunukul/Moondjan people of Minjerribah (Stradbroke Island in Queensland), it tells the tale of an elder, a granddaughter and the day a baleen whale came close to shore.

The whale, the older woman’s totem, is there to catch the grandmother’s spirit and take it out to sea.

“I want to celebrate the strength and simplicity of caring for knowledge that is passed down from generation to generation,’’ Page says.

In Page fashion, the story will be told through a mixture of traditional and contemporary dance, live vocals, prerecorded vocals, soundscape installations and instrumentation.

“And it’s over in an hour,’’ he says.

Page was approached by Adelaide Festival director Ruth Mackenzie, who asked if he would like to open the program.

Page has long had an association with the festival and was creative director in 2004.

“I just love Adelaide and I just love its landscape and the Kaurna caring of that,” he says.

“Country, north, south, east, west. There’s beautiful story-gathering grounds around Adelaide, and so the festival always, I think, charismatically really works for Adelaide as a storytelling place compared to Sydney and other sort of structurally based cities.

“It’s really the No. 1 festival in Australia, and to be able to tell this creation story on Kaurna country, on the Kaurna waters, is extraordinary.’’

Page says it took him about eight months to recover from leaving Bangarra.

There was a grieving process as well as a practical one. He found he needed a new email address, for one thing.

But the ideas and stories that had helped drive Bangarra since 1989 were always with him.

“My head and dreaming and imagination is always alive. I could have created this in insomnia; I’m always dreaming with my eyes open and thinking about stories,’’ he says.

Bangarra became one of Australia’s most successful artistic companies and cultural exports, starting from what Page describes as a blank canvas in 1989.

Born in Brisbane, he had performed with the Sydney Dance Theatre before starting Bangarra, which he says is the only “full-time, First Nations performing arts company in the world’’.

When the federal government wanted to highlight the force of Indigenous culture overseas, Bangarra was the name at the top of the speed dial.

“When the Department of Foreign Affairs wanted to have a mascot to celebrate the country, who did they call? Not, Ghostbusters: Bangarra,’’ he says.

It was Page who directed the Indigenous elements of the opening and closing ceremonies for the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games.

Page says he has a foot in both worlds “of First Nations and mainstream, working with contemporary and traditional art forms’’.

But always there was the importance of upholding the trust placed in him by other First Nations’ people to tell their stories.

“I put it (Bangarra) on that pedestal because it carries 65,000 years of inspired traditions,” he says.

“It carries this contemporary response through a black lens.’’

And Bangarra is uniquely Indigenous. And uniquely Australian.

As Page points out, all the other art forms in Australia are imported. Ballet, opera, classical music all arrived here.

And even if they are given an Australian twist or interpretation, their antecedents come from elsewhere.

Conversely, Bangarra and Page, now in his new incarnation, are tapping into tens of thousands of years of culture and storytelling formed on the Australian continent.

“(We were) working with First Nations communities all over the country who had trusted you as the sort of conduit between caring for stories and then presenting it in the mainstream,’’ he says.

“So you had all these cultural protocol responsibilities that were sort of part and parcel of just how you cared for stories.’’

But it was also an exhausting gig. Page describes leaving Bangarra as “coming off the Aboriginal sushi train’’. It was a leadership job, after all.

“You’re making decisions, you’re making sure they’re the right decisions, you’re doing business, you’re creating, you’re wearing many hats,’’ he says.

It was also a place where he worked with his brothers. Russell was a dancer with Bangarra and died in 2002. David, a composer, songwriter and conductor passed away in 2016.

The work helped Page cope with the tragedies.

“What was I supposed to do? Walk away from everything? I think everyone deals (differently) with grief and life and death, and especially First Nations people,” he says.

“I thought, ‘Why can’t I be here?’. ‘Why can’t I be healed by the beautiful?’. We get to work in the world of art and medicine and storytelling. We get to work in rekindling cultural stories, cultural practices, through dance theatre.’’

Which brings Page back to the story he wants to tell through Baleen Moondjan.

Page says, as he has become older – he is now 59 – and has become a grandfather, he thinks more about his own parents and what they endured.

Page was the ninth of 12 children to Roy and Doreen and grew up in Brisbane. Dad was a concreter and landscaper and mum worked in a cannery.

His parents were both from the Stolen Generation, and Page says they were forced to suppress their culture for much of their life.

But Roy would take the kids out to Beaudesert in the Gold Coast hinterland to pass on stories.

“I look at my parents, I look at the generations before me, my First Nations’ clans, and look at all the things that they could not celebrate in their cultural landscape – all the things they were displaced from,’’ Page says.

“From all the things that they were forbidden from, all that rich language of communicating which is the blood inside them, that is what it’s drained from them.

“That’s been one of the beautiful things about Baleen Moondjan: stepping into my own back yard and my mother and father’s country to inspire me for stories,’’ he says.

Page says it is a way of reconnecting with previous generations. It’s also a way of talking about death.

“I want to celebrate the totemic system, I want to celebrate death. I want to celebrate the death life cycle, so I want to celebrate what that means to us,’’ he says.

Page has created Baleen Moondjan with other long-time collaborators, co-writer Alana Valentine, composer Steve Francis, costume designer Jennifer Irwin and lighting designer Damien Cooper.

Among the 12 performers in the production are Elaine Crombie, playing the grandmother, and Zipporah Corser Anu as the granddaughter.

Page had to find six dancers, but couldn’t go back to Bangarra looking for talent.

Instead he recruited six former Bangarra dancers who were all out working in their communities.

But he said it didn’t take long for people to start asking questions about what his next project was going to be.

Page’s phone started to buzz. “They were like, ‘What are you doing on Glenelg Beach?. ‘What are you doing on that Kaurna country?’. They were all so inquisitive,’’ he recalls.

The audience will be seated on the beach. They can bring their own rugs or low-lying seats.

They will face north, the ocean on their left. As ever with a Page production, it’s an invitation to learn, a chance to more fully appreciate Australia’s timeless First Nations’ history.

Page uses phrases such as “conversations about sharing’’ and “re-educating this country’’.

Page veers between the highly optimistic and the righteously angry. His work is always optimistic; he believes it can shift the kind of national dialogue we have about healing and guilt.

It’s not even that hard to detect a note of positivity in his long-term dreams for Australia.

It’s just the here and now that brings the dark cloud. The Voice referendum was something of a tipping point.

“It was just awful; it was the worst thing I’ve ever felt,’’ he says. “It just shows you globally in the world, we are very immature.’’

Page calls it a “character reference of a country’’, and worries about the impact the rejection will have on elders.

“All those old people – all I was worried about was ‘How are we going to cleanse them?’. ‘How are we going to heal them mentally after this?’.’’

He says the debate generated unnecessary division within First Nations communities.

“And then once again, draining the spirit out of them. It’s another way of genocide. It’s just the psychological way of genocide. That’s what the referendum was,’’ he says.

Tongue in cheek, but mainly frustrated, Page says he “wants to go in and kidnap all my First Nations brothers and sisters’’ who are in parliament.

“All those great intelligent, cultural, intellectuals who know how to live with a foot in each world of politics and just look and grab the moment say, ‘Come on, let’s go and start our leadership foundation that’s going to create a plan for the future’.”

Page doesn’t believe there will be a proper resolution until Australia accepts responsibility and acknowledges its guilt for colonialism’s devastation of the continent’s original inhabitants.

He points to the maturity of a country such as Germany, which established the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in the middle of Berlin.

But he says accepting that guilt is the first step in a true process of reconciliation.

“As soon as they get over guilt, you would not believe how much pressure will ease,’’ Page says.

In the meantime, there is the refuge of art and culture. That is Page’s way of healing. That is what he wants for Baleen Moondjan. And he’ll make sure the tide spirit cooperates.