Australian of the Year, body image ambassador Taryn Brumfitt, wants to change the way we talk about our bodies

She founded an international body-positive movement and was named Australian of the Year. Now Taryn Brumfitt concedes she may have asked too much.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Taryn Brumfitt had some words ready – all Australian of the Year finalists have to, just in case – but was still flooded with nerves as she walked to the podium to accept the award of a lifetime.

“Of course, there is this moment of shock when you’ve got to pull yourself together really quickly because you’ve got to make the most important speech you will ever deliver,” says Brumfitt. “It’s quite a moment.”

Brumfitt spoke from the heart about the scourge of body shaming with its associated problems of anxiety, depression, anorexia and suicide. For 70 per cent of Australia’s schoolchildren, how they look is all they care about.

Worrying about size and shape has been a vexed problem for as long as anyone can remember, but Brumfitt has, in a decade, forced the issue into the mainstream, emphasising the power of early intervention and corrective messaging.

She hit the ground running and last month took her case to Canberra for a series of 20 meetings over three days with more than 60 politicians, including the Prime Minister Anthony Albanese whose mobile number she now has. They all loved what she had to say about the devastating, destructive power of poor body image and the suffering it causes, particularly among girls who carry the battle for thinness into adulthood.

“Every single person we spoke to was supportive of our mission and knows how crucial it is for our young people,” Brumfitt says.

But what comes next? Healthy thinking about size and shape is not a science and the answers are not clear cut; it will take a lot to shift deeply ingrained cultural ideals about what looks good and what feels bad. She now has a platform for dealing with one of the most insidious problems our affluent society faces.

She knows what doesn’t work. Well-intentioned public health messaging has only complicated people’s feelings further. In essence, the Life. Be In It-style campaigns that began in the 1970s, and which fat-shamed poor Norm into getting off his couch, have only made things worse.

“The message we have been receiving about our bodies, pretty loudly, over the past 20 years has (tried to) make us feel bad about appearance in an attempt to motivate us to engage in healthy behaviour,” she says.

“Not only is that ineffective, it’s been really harmful and has led to body-image concerns and eating disorders.”

She wants to change completely the way public messaging is delivered. The main focus of her Canberra trip was to seek support for a national awareness campaign to create new body-image messaging that stresses how we feel, not how we look.

“Our plan is to build really impactful public health campaigns that focus on doing the things that keep their bodies healthy, because it feels really good to do them,” she says. “I want to change the way we talk about bodies, weight and appearance so we can reverse some of this damage.”

This won’t be just aimed at size and shape but will encompass physical activity, cosmetic surgery and body diversity in advertising.

And she wants to focus on everyone, not just young people.

“Yes, absolutely,” she says. “I want it aimed at everyone, because everyone plays their role. The number of times I hear about grandparents who have said things that are so well meaning but damaging, like ‘you’ve put on weight’, being focused on appearance. And not just grandparents but teachers, kids, childcare workers, sports coaches.

“Everyone can benefit from an education around what it means to have a good body image.”

Her work on interventionist practices like cosmetic surgery is still in its infancy, but she has real concerns about “cowboy practitioners” who take advantage of people’s insecurities about how they look.

“There is work that needs to be done on both the supply and the demand side of cosmetic surgery,” she says.

“There does need to be more regulation – but we can also do the work to ensure that young people understand that cosmetic surgery isn’t a quick fix for anything.”

Her personal crusade began with a life-changing Facebook moment a decade ago when Brumfitt, a professional photographer, posted before and after pictures of herself as a weightlifter in a shiny bikini, and later in the relaxed and tastefully nude body she had come to love.

The response to that – mainly positive and admiring of her bravery but also sniping and critical – put her on a path to helping all women and children to stop judging their bodies and start embracing what bodies can do.

She might be sick to death of that photo but the movement gained impetus because it was Brumfitt’s own story; a woman who whipped herself into muscled perfection then realised counting calories and punishing herself at the gym was making her miserable. She dropped back and came to love her softer, rounder self that had given her children and a happier life.

So how did she do it?

“Well, I didn’t focus on weight, I didn’t focus on appearance, I focused on how I felt in my body,” she says.

“Instead of calorie counting and shaming myself to look different, I found gratitude for all the things that my body could do.”

To be clear, she is not asking people to stop caring how they look. As Australian of the Year, she invests in presenting well and takes care with hair and make-up like anyone else. It’s about finding balance.

“I’m not asking people not to get their hair done but it’s about making how I feel first, not how I look,” she says.

“I think as a society we have switched these two around and that’s why so many of us are not feeling good about who we are.”

After her Facebook post sparked international interest, including a Russian camera crew on her doorstep and talk show invitations in the US, she founded the Body Image Movement.

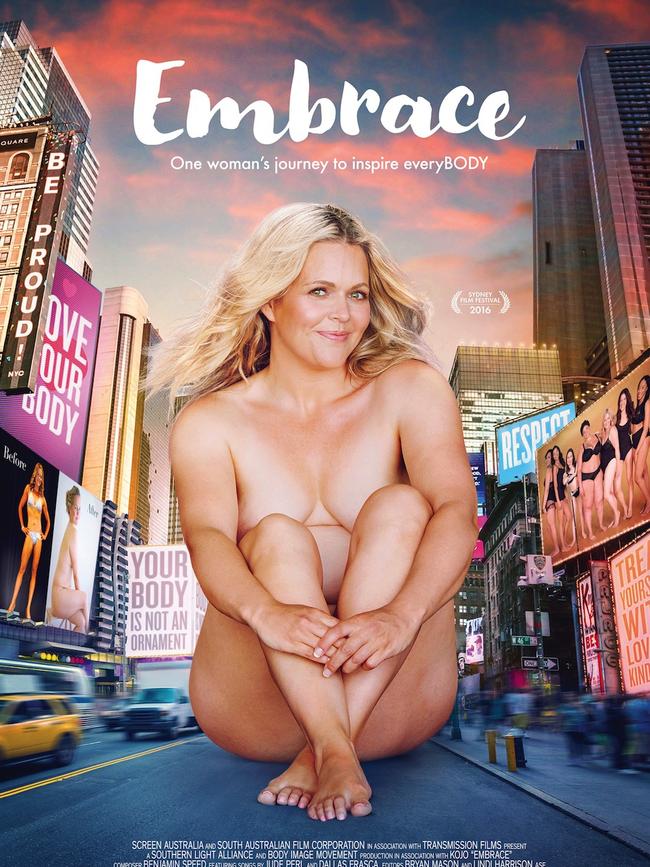

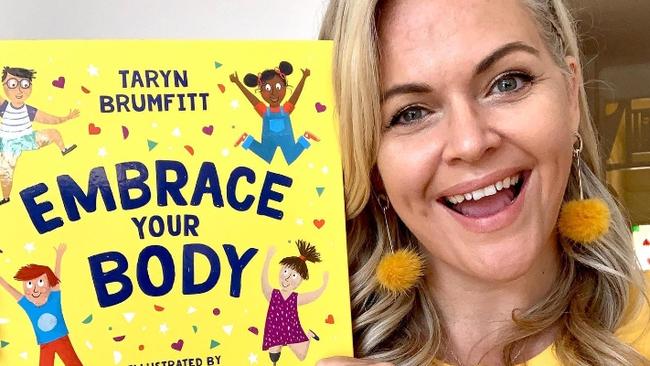

For a decade she has poured her energy into creating a series of tools to get that message across, with four books – Embrace, Embrace Yourself, Embrace Your Body and Embrace Kids, and two documentaries: Embrace the Documentary, and last year, Embrace Kids.

She has a studio and offices at Adelaide’s Glenside Studios and last year formed the Embrace Collective with Dr Zali Yager, an honorary associate professor and body image activist, to help guide the movement into the next decade. In the midst of the flurry of interviews, appearances and planning meetings, Brumfitt found time to get married.

In early March, in an intimate ceremony in the Adelaide Hills, Brumfitt, 45, married the love of her life, Tim Pearson, whom she met after her marriage to Matthew Brumfitt collapsed in 2020.

Wearing a handpainted silk dress, she and Pearson were married at the Bridgewater Mill, surrounded by family, friends and their four children.

“What’s not to love about Tim?” Brumfitt says. “Not only is he the kindest person I’ve ever met, he is by far the funniest. I have never laughed so much.”

This is her moment and her chance to make change.

She might still be on the same pathway but winning federal backing for community awareness campaigns would make permanent and accelerate the spread of the message she wants people to hear.

“Stigma and body dissatisfaction never helped anyone make good choices,” she says. “We need to dispel the myth around what it means to have a good relationship with your body.”

One of her goals as Australian of the Year will be to teach a million children to embrace their bodies. To do this, she is making the Embrace Kids classroom program available, free, to every school in Australia, broken into five different lesson plans so teachers can press play and know the subjects will be responsibly covered.

“It’s not about training the teacher, they’re too busy and often they don’t know what to say, so they say nothing,” she says.

She is also encouraging children to get involved and help spread the word. It might mean speaking up if something makes them uncomfortable, like a sports uniform that might feel inappropriate. If that happens, talk to your principal or write to your MP, she says.

“It’s about empowering them to go back out into their communities, regional, rural, with a change-maker project,” she says. “The only way we are going to reach a million is if everyone plays their part.”

Subliminal messaging about bodies comes from everywhere, from aunts and uncles to swimming coaches and dance teachers and Brumfitt wants to reach them all.

“I want online education for sporting coaches and community organisations to learn about how we talk about our bodies,” she says.

“We’ve had some pretty frightening feedback from parents about things that coaches have perhaps said to kids.”

Few things emphasised this more than the 2022 internal review of Swim Australia’s coaching practices which recommended dropping the so-called skinfold – fat pinch – test. Brumfitt says coaching should never be about weight and size but functionality. In a perfect world, shape wouldn’t come up in sport.

Overshadowing all this, including family, friends, school and sport, is the dead hand of social media which promulgates shifting norms of what makes men and women attractive, from swollen lips to tiny waists and Kardashian mega butts. Yes, but only if you invite the images in, Brumfitt says.

Rather than telling kids to get off social media, which would make them want it even more, she asks parents to show children how to fill their social media with other fun things. For once, cat videos are the answer.

“Demonising social media isn’t the key to solving this,” she says. “We have to empower our kids to understand that if you see images of bodies, it can lead you to compare and make you feel bad. Is that what you want? No, then fill it with non-appearance-based images.”

If not cats, then try following un-photoshopped comedians like Celeste Barber who made her name parodying the self-worshipping posts of some of the world’s biggest celebrities, including Beyonce and Bella Hadid. Brumfitt is all for using laughter to dismantle the threat and follows Barber with her kids.

Barber, currently starring in Wellmania on Netflix, based on a book about the wellness and weight loss industry, has this year been accused on social media of selling out because her body shape has changed. Brumfitt won’t have a bar of it.

“Her magic, her charter, her speciality, her super power is making people laugh and whether she is a size 12 or a size 16 doesn’t change that for me and nor should it for anyone else,” she says.

“We shouldn’t be critiquing anyone for changes to their weight, whether it’s weight loss or weight gain. That’s what we are saying!”

Her message of embrace has won her fans internationally. Hollywood star Ashton Kutcher – married to actor Mila Kunis – was an early supporter, as was US talk show host Ricki Lake, who wrote a foreword to Brumfitt’s first book, Embrace.

Earlier this month she was on stage in Melbourne at an ACMI event with two-time Academy Award-winning actor Geena Davis, star of Thelma and Louise, and the head of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media.

ACMI appointed Davis a goddess ambassador and brought her to Melbourne to lead a day dedicated to gender representation and diversity on screen and Brumfitt was part of panel discussions, along with Adelaide’s Sophie Hyde, whose recent film Good Luck To You, Leo Grande, was a masterful and entertaining exploration of a middle-aged woman trapped by her body image.

Brumfitt’s initial aim of getting people to love their bodies has softened since the movement began. The idea of being body positive and loving your body was too much to ask of women after a lifetime of shame. She worried the message would lose its power when it was equated with #loveyourbody, putting it beyond the reach of many.

“It’s a really big ask to expect people to be happy about their body when they loathe their body,” she says. “They are two ends of the spectrum and what we are saying is, you can head for the middle and be neutral about your body. You don’t have to love it; you can just be OK with it because you’re focusing on what the body does and not how it looks.”

She believes change is possible and says she would not be devoting her energy to it otherwise. Looking back over the past 10 years, she can see improvements, but things are worse too.

“I certainly hear a lot of good stories and I see a lot more brands doing the right thing, using more inclusive models,” she says. “But the statistics around eating disorders, anxiety, steroid use just in the last couple of years with the pandemic have been pretty alarming.”

As the Embrace movement moves into its second decade, her target has broadened. From her initial concerns about women and weight she now includes body image in different forms.

Her Embrace Kids documentary featured a non-binary teenager, an autistic girl, and launched into prominence the amazing Enzo Cornejo, an 11-year-old Adelaide boy living with progeria, the disease of premature ageing. Loved and supported by his family, friends and school, Enzo in the documentary projects confidence and happiness and just wants to get on with life.

“It felt obvious to include the voices of everyone’s lived experience,” Brumfitt says. “I think perhaps we need to remember that body image is not just size and weight, it’s appearance; it’s about how you feel about all of you.”

It is hard after meeting Enzo not to be swept away by his rock-solid self-belief, and his positivity inspires his teachers at school, his classmates – and Brumfitt. On the top of her Australian of the Year draft speech wrote the words: What would Enzo do?

“I read that before I did the speech because Enzo just shows up in the world as he is, unapologetic, confident, with pure joy, and he’s a truth teller, he speaks the truth,” she says. “I feel very grateful for having met everyone who made that Embrace Kids film but particularly Enzo. I know you shouldn’t have favourites but I do!”

Her announcement as Australian of the Year was praised by many and criticised by a few. Among her critics was Sydney author and former broadcaster Mike Carlton AM who tweeted that he would have preferred a frontline health worker doing real, compassionate work, “NOT someone who makes a buck out of saying it’s OK to be a bit fat”.

Brumfitt rolls her eyes and says she hears that at just about every talk she does. She cannot stress enough that body shame and weight stigma are serious issues that cause physical and psychological harm.

She also knows there could be people reading this who feel trapped in obesity and who, after a lifetime of struggle, might find it hard to hear that a change of mindset is all that it takes.

“What might be a good place for that person to start is to watch the Embrace film, which is on Netflix. We know that by watching that film people have a higher appreciation of their body image – and we know that storytelling is a great conversation starter, or heart opener, if you will,” she says. “It’s a good place to start.”

Obesity is at the pointy end of body image and nobody, including Brumfitt, is oblivious to the stampede of women trying to get their hands on a new weight-loss wonder drug, (Brumfitt asks us not to name the drug and says media guidelines about that will be coming out for that later in the year).

Designed to treat diabetes, the drug controls appetite and promotes weight loss. It is also expensive, stops working when the drug stops, has unknown side effects, and is potentially dangerous when sourced from an unreliable supplier online, of which there are many.

Brumfitt says it is not her place to oppose the use of a medical drug for a pharmaceutical purpose, that’s between a patient and their doctor. But the frenzy around the drug subliminally reinforces the narrow paradigm of beauty she is fighting so hard to break down, and which is only now starting to be challenged.

Anything promoting the idea of a silver bullet for weight loss undermines everything Brumfitt has to say.

“The media storm around these weight-loss drugs and the message that is being sent to our kids – who we work so hard to protect – is coming back to ‘you must be smaller and thinner at all costs, even when you don’t know the long-term side effects of something … all of that doesn’t matter because you will be thin’,” she says. “It’s not that the drug exists, it’s about the harmful messaging that sits around it.”

These are not trivial matters even though body image is often trivialised, and her elevation to Australian of the Year gives new authority to the body image message.

Brumfitt is the first South Australian to receive the award since 2019 when anaesthetist, adventurer and all-round hero Richard Harris (Harry) was jointly celebrated for his role in successfully extracting 12 boys and their soccer coach from a flooded Thai cave.

“I know Harry quite well and I feel humbled,” Brumfitt says.

She also, laughingly, says that she was first nominated in 2018 alongside Harris, which was the year when everyone but him knew they didn’t stand a chance. In January this year, a week before she was named Australian of the Year, she ran into Harry and his wife at Officeworks and stood there, armed with a year’s supply of stationery, for a 20-minute chat.

“He was one of the first people to congratulate me,” she says.

Recognition is hugely validating after a 10-year journey based on a struggle with her own body, and the freedom it gave her to get on with her life.

“The reason I have done all this is because I know that it’s possible for most people,” she says. “It comes back to my own personal values, that if you know something that can help others, you help them. I just didn’t understand it would be leading to this today.”