Alex Blackwell on fighting homophobic and sexist attitudes in cricket

Former Australian cricket captain Alex Blackwell has long battled for equality in sport and will never give up fighting to change the game she loves for the better.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dressed in a tailored suit and wearing pearls, Alex Blackwell took her place at the table alongside some of the most powerful administrators in cricket for lunch during the 2019 Sheffield Shield final.

Eddie McGuire, the then president of the Melbourne Stars Big Bash club, sat across from her and she enjoyed listening to what he had to say about the state of play in women’s football and cricket competitions.

However, Blackwell’s ears pricked up when comments around lesbians and “predatory behaviour” entered the conversation.

Blackwell was disappointed but certainly not shocked.

The former Australian captain had heard too many times before from too many men that lesbians were problematic for women’s sport.

She believed sports administrators were often disproportionately interested in what negative effect lesbians might be having on the game, compared with the focus they gave to issues such as sexual assault allegations in male competitions.

“They accept those things, because that’s what they think men do, it’s part of being a football player,” Blackwell laments.

“But the way women tackle, walk, the muscular nature of their bodies, the tattoos, the perceived gruff-looking face or the sharp haircut, that’s what’s not right to the gaze of many men. They can’t compute it.”

Blackwell was all too familiar with judgment and perceptions about lesbians – they affected her feelings about her own self-worth for much of her cricket career.

By 2019 though, at this luncheon with Australia’s sporting elite, she had learnt how best to handle it.

Recalling the conversation in her upcoming autobiography Fair Game, Blackwell said she knew that to Eddie McGuire, she probably didn’t look the way many imagined a lesbian would look.

She calmly asked him to expand on his comments.

“I deliberately used the language he had used when I asked ‘could you tell me more about this predatory behaviour’. I told Eddie, ‘I’m a lesbian,’ and I explained what he was talking about was really important,” she recalls.

“Instead of using language that profiles a group of people in a potentially discriminatory way I chose to shift the language of the conversation.

“I said to him ‘Eddie, the topic you are speaking of is really workplace behaviour, and it’s an important topic, however the language we use around this topic is crucial to get right’.

“With that small adjustment, I had moved the conversation from a potential argument about whether lesbians are good or bad for women’s football, to a broader and more effective topic of conversation for sports administrators to be having,” she explains.

“I didn’t tear him to pieces, but I did get my point across and he respected that.

“I noticed that no one else at the table spoke up when the topic of ‘predatory behaviour’ was raised, perhaps they found the topic too awkward. But I actually found the discussion quite invigorating and I was pleased with how I had performed.

“As someone who is well known for standing up for LGBTQI inclusion in sport, I could not let those comments from Eddie go by without being addressed.

“I also see that it’s up to people like me, who have taken notice over many years of the way LGBTQI people are welcomed or not in sports, to participate calmly in conversations like this in order to effect change.”

For Blackwell, who captained the Australian women’s cricket team through World Cup and Ashes victories, this was a proud moment.

She had reached the point in her life and career where no one could hurt her anymore.

“I knew I was fine. I know I am a worthwhile human just as I am,” she says.

“And I no longer allow comments like Eddie’s to affect me personally.

“It’s unlikely that I was able to change Eddie’s views about lesbians who play sport in that one discussion. But the conversation we had just might simmer in his mind, like it has done in mine.”

The Blackwell of 2019 was very comfortable in her own skin but that wasn’t always the case.

COMPETITIVE CRICKET AND SEXUALITY

Blackwell, 38, knew from a very early age she loved cricket and grabbed every sporting opportunity with both hands.

Her attraction to women was something she suppressed for many years – the fear of being rejected by those in the sport she loved was too big a risk to take.

“I spent so many years feeling like being gay was less desirable and not the image that people wanted to see in our sport, that it has affected me very deeply,” she says.

Blackwell and her sister Kate were the first identical twins to play cricket for Australia.

Around that time she started being asked “by older men at functions” about how many members of the Australian team were gay.

They tended to be people who didn’t know too much about women’s cricket and for some reason that question was high on the agenda.

“I would think to myself, ‘So how many would you consider acceptable? One? None?’

“Being so young, I didn’t realise that I didn’t have to answer those kinds of questions but those men were important guests who were much more influential than I was, so I fell into the trap of answering them.

“I could tell from their tone that they didn’t think having a lot of gay women in the team was a good thing; that this stereotype of cricket being full of lesbians was a negative one in

their eyes.”

Blackwell regrets trying to come up with the “right” answer.

“As a young person trying to come to terms with my own sexuality, it was difficult to have to field those questions and receive yet more confirmation that my sport and my society didn’t want me to be who I truly was,” she says.

University was the most complicated time in Blackwell’s life. She pushed herself to the limits physically as an Australian cricketer and intellectually as a medical student at UNSW. And these two pursuits did not leave space for her to properly understand her identity.

“I never let myself go and enjoy the experiences that were on offer. On top of those stressors, I was becoming increasingly aware of the discomfort I was feeling about my sexuality,” she says.

“I never let myself be free to meet someone and form a relationship because I didn’t want to have those feelings for women.

“It just felt like being gay was less desirable for a female cricketer. I didn’t want to be like that.”

Her attitude probably helped her be a high achiever. Without the distraction of relationships, she could throw herself into cricket and study.

This gave her an escape from the “deep shame” she was feeling about who she was turning out to be.

Blackwell made cricket her focus and in 2006 was excited to be a member of the Australian team invited to the Allan Border Medal award ceremony for the first time.

“While the male players were able to bring their partners and bask in the attention of the media on the red carpet, the women received invitations just for themselves,” she says. “Looking back, I can’t help but feel that it was potentially deliberate, to make sure none of us brought along a female partner.

“Even when we were eventually allowed to bring partners, it was some time before most people felt comfortable bringing female partners. Players would often bring their father, brother or sister along instead.

“But in those early days we had no choice to bring anyone.”

That night in 2006 was “quite ridiculous”.

“The women’s team were all seated together at one table, right at the back of the room, and our presence was barely acknowledged,” she says.

“We had just won the World Cup, but that wasn’t spoken about at all.

“The only time we were mentioned was in relation to the men’s team losing the infamous 2005 Ashes series in England, when the MC reminded the room that the women’s team had also lost the Ashes that year.

“Even worse than that was a total lack of celebration or even acknowledgment of Belinda Clark’s retirement.

“Belinda was arguably our greatest ever captain and the most significant player of our generation, someone who threw her heart and soul into cricket for many years for no money and barely any media attention.

“And the moment was just allowed to pass by.”

Blackwell says she couldn’t imagine the same thing happening if the men’s captain at the time, Ricky Ponting, had announced his retirement.

She felt more uncomfortable the more she played the night over in her mind.

She wrote a letter to Cricket Australia’s chief executive, James Sutherland, to express her concerns.

It was a gutsy move for a 22-year-old who hadn’t long been in the Australian line-up.

“I can’t imagine what James thought on receiving the letter; possibly he thought I was too forceful in the way I worded it – I was very direct.”

Blackwell was never shy to lock horns and stand up for what she thought was fair, though she gradually learned that head-to-head confrontation wasn’t always the best strategy.

She developed her own way of calling out inequality – a more calm, controlled approach, one you would come to expect from a national captain accustomed to handling high pressure situations.

She began to use the blows she copped – such as being made to feel she wasn’t straight enough, wasn’t blonde enough to warrant a marketing contract – to fuel her fire and work towards making the game she loved more inclusive.

“There’s something magical about cricket and I think everyone should feel like they can be a part of it if they want,” she says.

“It’s the ceremony of cricket, the choosing of a new cricket bat, the knocking it in with some linseed oil, the sound and sensation of hitting a ball right out of the middle of the bat, there’s nothing like it.

“I want everyone to have the chance to experience it.”

FIGHTING STEREOTYPES IN WOMEN’S CRICKET

Blackwell was just five when she first pickedup a bat on her grandparents’ farm near Griffith, NSW, and her first teammate, and opponent, was her twin sister Kate.

In their early days of competition across the southwest of NSW, boys didn’t take too kindly to being beaten by girls, but the talented Blackwell sisters soon earned respect.

The pair grew up in Yenda, a small town just east of Griffith, and later boarded at Barker College, on Sydney’s North Shore.

They rose through the ranks of representative cricket for their clubs and state, and eventually became the first identical twins to play for Australia.

Blackwell represented Australia 251 times across Tests, one day internationals and T20 internationals, with the team winning the World Cup in 2010 and the 2011 Ashes under her captaincy.

She was the first woman to play more than 200 matches for the Australian cricket team.

“If I was a male cricketer, I may have already released a couple of Ashes diaries and a biography by now, with mixed success, and so I thought why not write my story,” she says.

“To read a book by Australian cricket captain Belinda Clark or world-beating pole vaulter Emma George would have been a dream to me as an emerging female athlete. Sadly, in reality there are few books out there about female athletes.”

Blackwell sees the progress female athletes are making and is passionate about being at the forefront of a more inclusive sporting world and society as a whole.

She sums up her career as a good cricket career, not a great cricket career, “but my time in the game has absolutely changed my life for the better”.

“From travelling to parts of the world I could not have dreamed of like Mongolia and Japan, to representing my country alongside my twin sister, to meeting the woman I have chosen to spend the rest of my life with, this sport has given me so much joy.”

However, becoming an advocate for increasing diversity and equity in sport has given Blackwell the greatest amount of pride.

Her courage to tackle difficult conversations head-on and lead by example – such as the time she wore her baggy green cap on a Sydney Mardi Gras float – has helped bring about change.

“It was the difficult experiences I had off the field, as a gay woman in the male-dominated and homophobic world of sport, and as someone willing to speak up for what I believed in, that has been the real making of me,” she says.

“While I wish the hurtful experiences of homophobic and sexist attitudes in sport were not a part of my story, I wouldn’t trade them now.

“These experiences have been gifts which have helped me realise that, despite the negative messages I received, I like the person I am, including the gay part.”

Since her retirement in late 2019, Blackwell has continued to be involved in the game as a board member, commentator on Fox Cricket and ABC Grandstand, and media spokesperson.

While great progress has been made, she feels there is more work to do.

“The way we talk about the women’s game versus the men’s game – it’s still shown in a slightly less valuable light, just in subtle ways,” she says.

“Ticket sales for the women’s game compared to the men’s game? Like how many people are we trying to get through the gates for the women versus the men?

“Subtle things can make such a difference, like the way they talk about female athletes and male athletes at the awards night, and you can tell when it’s genuine, you can tell when there’s a genuine view that these women are crucial to our business.

“What order do we celebrate the men’s and women’s awards in?

“You’ve got the female player of the year and then you’ve got the male player. It’s always in that order. Why don’t we alternate this?

“Why is men’s first grade premier cricket played on Saturdays while the women have to play on Sundays?”

Blackwell is proud she’s not afraid to talk about things that are unpopular and not always easy.

“While I’m shining a light on some not so great experiences I had in cricket, I also want to show how much I loved playing the game. And we need to make it even better by being welcoming of all types of people just as they are.

“I’d like that to be the reality for all our diverse young people in this country, that they can see that cricket has a spot for them.”

Blackwell has been looking forward to the women’s Ashes series, underway now, but has a busy year ahead.

On Christmas Eve she began maternity leave from her job as a genetic counsellor and

is expecting her first child in February with her wife, former English cricketer Lynsey Askew, 35.

“I’ll cover some of the women’s Ashes with the Fox cricket commentary team. I’ll be pretty big,” she jokes.

“Maybe it’ll be a good thing to see a pregnant woman on the cricket commentary team, normalise it a bit.”

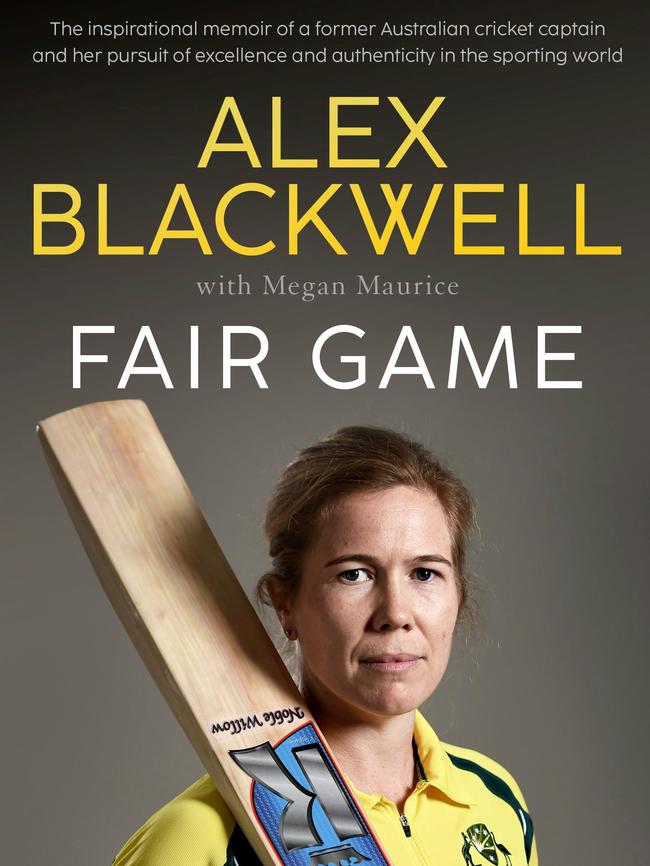

Fair Game by Alex Blackwell, Hachette Australia, $33, out Wednesday

More Coverage

Originally published as Alex Blackwell on fighting homophobic and sexist attitudes in cricket