Adelaide Festival 2022: Six shows you can’t afford to miss

Next year’s Adelaide Festival looms as a celebration of both milestones and the end (hopefully) of lockdowns. Here are six shows not to miss.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Halfway through Australia’s second year of pandemic lockdowns and border closures, Adelaide Festival artistic directors Neil Armfield and Rachel Healy have gone to extremes to maintain the event’s international flavour and standing in 2022.

“We have come back from Europe full of optimism having witnessed audiences return with gusto to theatres, fully masked, double vaxed and filling every seat,” they say in their introduction to next year’s program.

“But we’re all too aware that this sunny ideal has as its dark twin.

“In the face of all this, our commitment to deliver a festival that energises, comforts and reasserts the necessity of human creative imagination remains.”

The program’s 71 events range from UK theatre company Donmar Warehouse’s immersive binaural sound and lighting experience Blindness, through Barrie Kosky’s Aix-en-Provence opera production of The Golden Cockerel, to London’s Chineke! classical music ensemble and Sydney Theatre Company’s acclaimed re-imagining of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.

It is also a year of marking anniversaries for milestone events in the history of the Festival and Adelaide itself.

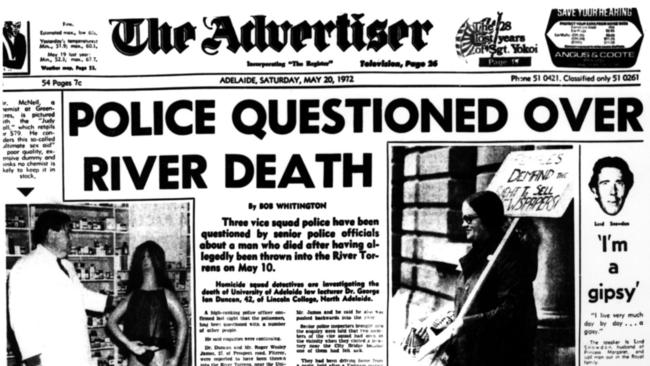

“We are celebrating the 30th anniversary of that brave, first Womadelaide … the 40th anniversary of seminal Aussie band Icehouse’s anthemic Great Southern Land and … a darker milestone: the 50th anniversary of the 1972 death of Dr George Ian Duncan.”

Here are six shows not to miss:

WATERSHED: THE DEATH OF DR DUNCAN

Fifty years ago next May, a body was removed from Adelaide’s River Torrens that would spark public outrage, a Scotland Yard investigation, a trial, and lead the way for international homosexual legal reform – but would never result in the conviction of those responsible.

Until that moment, few had heard of unassuming academic Dr George Ian Ogilvie Duncan, but his name would resonate around the country and down through the decades as a clarion call for change.

To mark the anniversary, Adelaide Festival artistic co-director Neil Armfield is creating Watershed: The Death of Dr Duncan, an oratorio which will bring together some of Australia’s leading queer artistic voices, span events in the lead-up to and wake of the drowning, and celebrate its profound and lasting impact.

“It looks backwards and forwards,” Armfield says of the choral work.

“There is a sense of trying to take in the shifts of popular opinion, and look at the courage of people who knew that this was a murder, who have tried to get to the truth of it.”

The idea came from a conversation between Armfield and Helen Sheldon, chief executive of queer festival Feast, who had heard a talk on Duncan’s death by her neighbour, Adelaide historian Tim Reeves.

Duncan was born in London in 1930, the only child of parents from New Zealand, and spent his education years – which were interrupted by tuberculosis – moving between Melbourne and the UK.

In March, 1972, Duncan returned to Australia to lecture in law at the University of Adelaide and moved into Lincoln College at North Adelaide. Six weeks later, on May 10, he was thrown from the southern bank of the River Torrens, near Kintore Ave, and drowned.

Duncan was one of three gay men that night who were thrown into the Torrens – a known “beat” where homosexual men met for sex – by a group of what witnesses would later identify as police officers.

“There was the extraordinary palaver with the three cops from the vice squad who were seen down at the river that night, who were allowed to resign from the force so that they were private citizens by the time they came to trial, so they were able not to give evidence on the grounds that it could incriminate them,” Armfield says.

“Then the extraordinary courageousness of Mick O’Shea, who was on the vice squad himself and blew the whistle in ’85. He acknowledged the practice that these vice squad officers had of what they called ‘teaching the poofters to swim’ – of going down to this beat at the Torrens and throwing the gays in.

“It was indeed the finding of the second Scotland Yard inquest that (then premier) Don Dunstan called – after the first inquest released an open verdict – that the vice squad cops did it.”

After three years of attempts, on August 27, 1975, the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Bill was finally passed, making South Australia the first state in the English-speaking world to fully decriminalise homosexuality.

“No one has ever been brought to justice for that murder of Duncan. But what has happened is that South Australia by 1975 led the world in terms of civic reform,” Armfield says. “It’s an incredibly important moment, not only in Adelaide’s history, but in Australia’s history.”

To write the Watershed libretto, Armfield teamed playwright Alana Valentine (Barbara and the Camp Dogs) and author Christos Tsiolkas (The Slap), who had never worked together before.

“I loved the idea of a queer team putting this particular story together,” Armfield says.

“Alana, with her extensive experience in writing verbatim works for theatre and a really strong interest in social justice and social movement, and Christos … I thought it would be great to have an understanding of the kind of atmosphere of sexual tension and darkness and fear, and internalised homophobia that exists on gay beats.

“It’s an area that Christos, in his novels, has delved into.”

Tsiolkas, whose novel The Slap was made into two TV series in Australia and the US, and whose earlier work Loaded was adapted as the controversial 1998 film Head On, says it was important to give the Watershed project an authentic voice.

“In a way, there’s a sense of requiem, because it was such an ugly event. Part of this work is to honour someone who was just so mercilessly killed, but there is also a celebration about it,” he says.

Even though he was only 10 when SA decriminalised homosexuality, Melbourne-based Tsiolkas remembers being “quietly thrilled about it”.

“Even back then, I had a sense that it meant … something for the world, but something for me, too, just that knowledge of one’s self that you didn’t even dare talk about at that time. I didn’t even know if I had the words to consciously express it. So it feels terrific to be part of this project.”

Sydney-based Valentine, who wrote the libretto for acclaimed song cycle Flight Memory and has featured songs in many of her plays including The Sugar House, Head Full of Love and Ladies Day, says the choice of musical form is also provocative.

“Oratorios are for sacred heroes. One of the things that making this an oratorio about a gay man who was murdered is say this is one of our sacred heroes, and we are going to treat him in the most musically eloquent way. It’s beautiful – when you sing about the tragedy of somebody’s death, it really transforms the cognitive, rational approach to that thing, by making it pure emotional sensation. You do that for revered figures: the classic oratorio is the Messiah (by Handel),” she explains.

“It claims a religious space in a way that gay and lesbian people crave.”

Queensland composer Joseph Twist – whose work spans from arrangements for pop artists like Kate Miller-Heidke, to songs for children’s TV acts The Wiggles and Bluey, to film soundtracks, and chamber choirs – was commissioned to do the score.

“It’s like taking Handel to Mardi Gras,” Valentine says, prompting an outburst of laughter from Tsiolkas.

“I think that there will be a contemporary music breakout,” she continues.

“Most of it will sit in the oratorios – this is a sad story, a serious subject – but of course there is joy in there and celebration. It’s a gay piece, hey … it’s not going to be too dour.”

Twist previously composed a Mass for Christ Church St Lawrence in Sydney, where Armfield had attended and sung in its choir as a teenager.

“It was the church of actors and a slightly queer elite in Sydney,” Armfield says.

“It always had a very strong social function – it’s down near Central Station and had an outreach to the homeless, a really interesting place for a 16-year-old like me.”

Armfield and Tsiolkas say the fear and threat of physical assault were common experiences on gay beats around the Australia at the time of Duncan’s drowning, and for many years after.

“It became worse in the ’80s, once AIDS hit the country. In Sydney there were a string of murders and bashings, some of which are just being solved now. At the time, the police had no interest at all,” Armfield recalls.

“I was bashed in ’86, and was basically told it was my fault, for being in a park.”

Tsiolkas says Watershed goes beyond Duncan’s murder to explore its effect on the wider community.

“It’s not only this man – there was a whole wave of violence that has a long, awful history and is, in many ways, still continuing,” he says.

The creative team also includes SA choreographer Lewis Major, who presented two works in the 2021 Festival, although Armfield says they are still determining how movement will fit into the work.

“I went to a creative development … and Lewis was playing with ideas of the isolation of a figure above water. It just seemed like, in some ways, he had answered ideas or images we had actually been talking about in the room the week before,” Armfield says. “I think it needs some real theatrical imagination in finding the physical shape of it.”

The co-production with Feast and State Opera will feature soloists, a 12-instrument ensemble and the Adelaide Chamber Singers, conducted by Christie Anderson.

Recent changes in legalisation for gay marriage, representation and broader recognition of gender diversity have also made it timely to revisit Duncan’s case.

One of the aspects Valentine and Tsiolkas discussed was the difference between what happens legislatively and what happens in the community.

“The community sense and feeling has to be the motivator and the thing that pushes that legislative change. We saw the most amazing young people get behind the idea of marriage equality and change – not just gay and lesbian people, this was a widespread thing,” Valentine says.

At the time of Duncan’s drowning, Armfield was completing his High School Certificate and had directed his first play. He recalls news reports of Duncan’s death, but says its significance only sank in later.

“I suppose I had an eye for stories of gay interest … it was also, I guess, the year I came out, to my parents anyway,” he says.

“Once I was living in Adelaide in ’82, I became profoundly aware of the legacy, and also that weird dichotomy in Adelaide of leading the world in so many social reforms – but there being a dark side … these weird ironies and tragic crossovers.”

One of those strange connections was that the person who came to the rescue of Roger James – another gay man thrown into the Torrens that night – was Bevan Spencer von Einem, who was later convicted of the 1983 murder of 15-year-old Richard Kelvin, one of the so-called Family killings of young Adelaide men.

“There are these weird ironies and tragic crossovers. Someone got into the zoo and killed all those animals … there’s a strange, dark underbelly down around the Torrens and that valley that runs through the city. I was always very interested in that sense of a double life in Adelaide – a city that was formed from the highest principles and was not tainted by the stain of a convict past, and so beautifully laid out on Kaurna land. But underneath that civic order was a very unsettled sexual underbelly.”

The fact the case has never been successfully prosecuted, and remains legally unsolved, makes it rich dramatic material.

“With police now marching in Mardi Gras and having gay and lesbian liaison officers, there has been a huge change, and we acknowledge that … but there’s no shying away from the fact that there are still questions to be asked,” Valentine says.

“There are many who feel that justice hasn’t been satisfied.”

Watershed: The Death of Dr Duncan, Dunstan Playhouse, March 2-8.

CHINEKE! CHAMBER ENSEMBLE,

As an acclaimed double bass player and Royal Academy of Music professor, Chi-chi Nwanoku has fearlessly and fiercely blazed a trail for black and ethnically diverse classical musicians – and composers of colour – to be seen and heard on the international concert stage.

When she brings her groundbreaking Chineke! Chamber Ensemble to Australia for the first time as part of next year’s Adelaide Festival, joining a list of personal accomplishments which already includes an MBE and OBE for services to music, British-born Nwanoku will add the voice of Aboriginal composers to its ever-expanding repertoire.

But none of that might ever have happened if she hadn’t been persuaded to take part in a women’s soccer match 48 years ago.

Until that fateful day, then 17-year-old Chi-Chi was set to become an Olympic sprinter and had never contemplated music as a career.

“I was in my final year at school and I was preparing for Montreal actually – the 1976 Olympics. I’d just missed qualifying for Munich when I was 16,” says Nwanoku, who had been spotted by a sprint coach at the age of eight.

“I received a phone call from a women’s football team in the town we lived in. I didn’t know that women had started playing football officially … I used to play great football with my brothers.

“This women’s team called me and said ‘Chi-chi, we’ve lost our main striker to injury and wonder whether you could step in and help us for a game or two?’ I just said sure … I’d played county hockey, I’d played county netball, and I was a sprinter. I’d never had an injury in my life.”

All of that was about to change.

“Honestly, it was the most awful experience. Every single time I ran with the ball … apart from the goalie, I’d have 10 people trying to kick me to pieces,” Nwanoku says from her London home.

“Finally, one person connected with my right leg as it was travelling through the air, kicked it brutally from the side, dislocated my knee very badly – and that was my career over in a split second.

“It was devastating. I was taken off in a stretcher to accident and emergency, and they said you’ll be operated on but you won’t sprint at national level again.

“In those days, the repair work was not as it is today.”

If there was anything that Nwanoku had inherited from her Nigerian father and Irish mother, it was a sense of determination in the face of adversity – along with knowing the importance of an education.

“In this couple of weeks that I had to wait before my surgery, I just did extra piano practice. I played the piano and the recorder as a passionate hobby, and I was reading A-Level music in my final year at school,” she says.

“I’d heard about this school annual music competition, which I had never entered. I thought, how weird to go into a competition where you’ve got the piano against the bassoon, against the flute … it must be like running the 100m against a pole vaulter.”

Nonetheless, Nwanoku entered the competition to help pass the time, “played some Chopin” – and won.

On returning to school after two weeks in hospital, Nwanoku was informed by her music teacher John Dussek that the prize she had won was for free music tuition. While Dussek and the headmistress didn’t feel Nwanoku could ever be a concert pianist, he said they believed she could still have a career in music “if you took up a very unpopular orchestral instrument”.

“He took me to this room that I’d never been in before, and in that room stood two double basses,” Nwanoku recalls.

“I looked at him and said: ‘But I’m the smallest girl in 6th form, I’m five-foot-nothing, and that’s got to be the biggest instrument in the orchestra’. A week later, I was having my first bass lesson and the rest, as they say, is history.”

Does she now look back on that injury as the best thing that ever happened to her?

“Absolutely,” Nwanoku, now 65, laughs. “People tease me, they say: ‘Chi-chi, you’ve swapped your legs for your arms’.”

During her career Nwanoku has been principal double bass of ensembles including Endymion, the London Mozart Players and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, and been active as a broadcaster – in particular presenting radio programs on black classical composers and performers.

In 1986 she became a founder member of the period instrument group Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, of which she remained part for the next 30 years.

However, in 2015 Nwanoku decided to start her Chineke! Foundation and its accompanying orchestra with the express purpose of providing “career opportunities to young Black and Minority Ethnic classical musicians in the UK and Europe”.

Nwanoku’s full first name is Chinyere, which comes from her father’s Igbo language.

“My name means the same as Dorothy, actually – a gift from God,” she says.

“It’s the god that they believe is your guardian. Every single individual has their own chi that guides you from your cradle to your coffin.

“The Igbo language has travelled across the globe … if you think of ‘chi’ in China, it’s basically your life force.”

Her orchestra’s name combines the Igbo words chi (god) and neke (create): “I interpret it as the spirit of all good creation.”

Chineke! made its first commercial recording the following year, and in 2019 became the first recipient of the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Gamechanger Award for transformative work in classical music. In August, the orchestra – which has also included white musicians – gave its fourth BBC Proms performance in just six years.

“It screams from the rooftops that this is what people want to see … orchestras and this section of the creative industry looking and sounding more inclusive.

“Right from the start I was absolutely clear that I was not interested in creating this organisation and just sprinkling a few black, brown, beige faces across the stage, and then calling it diverse and inclusive.

“Repertoire is also key – we include at least one piece of music in every concert that is by a composer of relative ethnicity, that can share the stage with Beethoven. We’ve found the most glorious repertoire that has always been there, that has always stood alongside the popular composers from the great canon – but they’ve simply been excluded.”

Nwanoku is also at pains to avoid stereotypes when describing how the orchestra’s ethnic makeup affects its playing.

“We’ve got to be very careful about saying black people are good at rhythm, and white people are good at melody and harmony, because that is an overused and quite offensive statement.

“It’s just a myth, really. No two people have the same ethnic makeup, usually, in the Chineke! Orchestra, which adds to such an incredibly exciting mix. Each person has been classically trained … but of course each person has their own cultural mix inside them. I think it’s very subtle, but each person brings a little bit of their own self, a little bit of their own background and culture.”

In Adelaide, each of the programs performed by the 10-player Chineke! Chamber Ensemble will include one of two newly commissioned works by First Nations composers, didgeridoo player William Barton and soprano singer Deborah Cheetham.

Nwanoku says that the UK’s black composers have not been commissioned or performed as often as their white contemporaries. Chineke! has commissioned an average of two new works a year from composers of different ethnicity who now live in England.

Changing the racial makeup of an orchestra and its repertoire immediately affected who constituted its audiences.

“We’ve attracted a broader type of people,” Nwanoku says. “Metaphorically, that door has been cracked open – but it has also literally opened, because the audience now very much more reflects the community that we live in.

“I’d been on the international concert platform for 35 years, and I was usually the only black person – not just on the stage, but in the entire building: in the audience, the stage, the repertoire, backstage.”

The subject of doors being opened is one which, again, has very deep personal significance for Nwanoku.

Her Nigerian father, Michael, studied at the Open University to be a psychiatrist, while her mother Margaret was an Irish nurse whose own parents disowned her for having an interracial relationship.

“Both my parents, when they came to England, came from countries that had been colonised by Britain.

“When my parents met and they wanted to be together and they tried to find a room to rent … there would be that sign: No blacks, no dogs, no Irish. But they had an incredible sense of humour.

“They would look at each other and say, ‘Well, we haven’t got a dog, so that’s only two out of three – let’s knock on the door’.”

Chineke! Chamber Ensemble, Adelaide Town Hall, March 16-17.adelaidefestival.com.au

JULIET & ROMEO

Alternate realities might sound like something from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but Scottish dance theatre company Lost Dog has created its own multiverse by asking the question: What if Shakespeare got it wrong?

Juliet & Romeo is based on the premise that the Bard changed the ending of the star-crossed lovers’ real-life story to make it a tragedy, and that the couple has in fact been living ever after – if not always happily.

Lost Dog was started 10 years ago by artistic director Ben Duke and associate artist Raquel Meseguer Zafe. They were joined in 2012 by dancer Soléne Weinachter, who will play Juliet to fellow performer Kip Johnson’s Romeo at this year’s Adelaide Festival.

“Ben had the idea of looking at a realistic perspective on love and relationships in our culture,” Weinachter says from Cornwall in the UK, where the company has been on tour.

“Romeo and Juliet being one of the foundation myths on how love functions, he wanted to unpick that.

“We explored all kinds of scenarios, all kinds of stories, all kinds of different things that may have happened to Juliet and Romeo, before finding the show we have today.”

In this version, the couple are now in their 40s and have their own family.

At least one of them is going through a midlife crisis, and they feel continually mocked by their idealised teenage selves.

The structure of the work, which combines dialogue and physical theatre, allows the characters to look back at key passages from Shakespeare’s play, as if they were memories.

“When we meet the characters, they are in a crisis – they have been struggling for a while,” Weinachter says.

“They’ve tried a lot of things to help their relationship – they’ve tried couples’ therapy, they’ve tried (psychoactive brew) Ayahuasca, they’ve tried couples’ massage … and none of it has worked.

“So they have decided to try one more thing, to put on this experiment with the audience – which just has to listen, almost like when you go to the therapist.

“In those memories, we have taken key moments of the (Shakespeare) play – if you know the play well, you will know what we are referring to. If you don’t know the play, it will still make sense – although most people know the play.

“We go on and make more memories … like their first child.”

French-born Weinachter says Dundee in Scotland is now becoming her home.

“For a long time, I didn’t have a home. Until coronavirus, for almost two and a half years, I lived in my suitcase – because of all the shows, I didn’t need a place.”

Although many may consider Paris to be the home of dance, Weinachter chose to study at London Contemporary Dance School, also known as The Place.

She landed her first job in Scotland, where she was then invited to join its national Scottish Dance Theatre company in 2007. There she met freelance choreographer Duke and worked with him to create a piece called The Life and Times of Girl A.

Juliet & Romeo is the most recent and most in-demand of the three works Weinachter has made with Duke. As well as combining dance and theatre, the work fuses drama with comedy.

“We are playing with the Shakespearean form … within the tragedy there is definitely comedy.

“I would say this one is more funny than tragic, but there’s a big chunk of sadness in there as well,” Weinachter says. “There were some scenes that were easy – for example, the ball of the Capulets, where we had to make our own dance.”

So, do things pan out better for Juliet and Romeo this time around?

“Hmmm – I think that’s for you to decide,” Weinachter says.

“People have had different interpretations of it – we’ve gone for something that doesn’t really make it easy for the viewer.”

Juliet & Romeo, Scott Theatre, March 5-12. adelaidefestival.com.au

AFTER KREUTZER

First came Beethoven’s 1803 sonata for piano and violin, commonly known as the Kreutzer Sonata. Then, ignited by the music’s sweeping passion and fury, came Russian author Leo Tolstoy’s controversial 1889 novella of the same title.

Now, Adelaide author and pianist Anna Goldsworthy is bringing both words and music together in After Kreutzer, which also takes inspiration from the more recently uncovered response to Tolstoy’s work by his wife, Sophia Tolstaya.

Goldsworthy developed the work during her time as artist-in-residence at the Melbourne Recital Centre, where a pilot performance was held at the Primrose Potter Salon earlier this year, ahead of its inclusion in the 2022 Adelaide Festival.

“The project emerged from a sense that had been growing in me for years, which was about how much art is based on the death or the debasement of a woman,” Goldsworthy says.

“In fact, Edgar Allen Poe said the most poetical of all subjects is the death of a beautiful woman.

“I was taking a tour group around the opera festivals in Salzburg and Munich and elsewhere in Europe a couple of years ago. I’ve always loved opera, and I’ve always been mindful of the fact that opera has this slightly problematic subtext, a narrative drive which is often about extinguishing the female.

“I was kind of overwhelmed on that occasion, because I went to eight (operas) in a row. It made me look around more broadly at the art that I love, and perhaps at my complicity in the art that I love, in which the woman has to die. That includes murder ballads and all sorts of things.”

Goldsworthy says that, in literature, these experiences are often presented from the view of a male protagonist, “and less from the perspective of the woman who is cursed to die”.

“The ultimate example of this, in a way, is the brilliant but really conflicted and troubling novella by Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata.

“Coincidentally, Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata for piano and violin is one of my favourite pieces to play: so visceral, so exciting, so charged with this sort of muscularity. I’ve often imagined, quite separately, what it would be like to be a woman in a drawing room, playing this piece in the 19th century?

“In a way, the emotional contour of the piece transcends what would normally be permissible for a woman in polite society. It’s a piece that rages and triumphs and celebrates and dances – it’s full of the most unbridled passion.

“It’s a piece that obviously affected Tolstoy … he’d heard a performance at his home, and thought that might make a good centrepiece for this novella.”

In Tolstoy’s story, his protagonist Pozdnyshev recounts alternate periods of passionate love and vicious fights with his wife. She takes a liking to a violinist and they perform Beethoven’s title work. Pozdnyshev hides his raging jealousy but, when he returns early to find them together, kills his wife with a dagger.

Seen as an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence, it was originally banned by Russian censors.

Goldsworthy wanted to find a way to bring Tolstoy’s and Beethoven’s elements together, in a performance which will also feature Sydney Symphony Orchestra concertmaster Andrew Haveron.

“Re-reading this novella, it is so compelling. Even the way Tolstoy describes the murder of the wife – it is very modern, the way he lingers over the moment and he can feel the resistance of her corset on the dagger, the physicality of the actual murder. It’s so immediate … and so fully realised, that I thought it would be interesting to try and imagine what it was like to be the woman.”

At that time, Goldsworthy says there was also a “charge of female rage” surrounding the #MeToo movement, rape allegations and the treatment of women in federal politics.

“I was able to access that in the writing of this piece. It speaks to the absolute blight on our society that is the ongoing problem of domestic violence.”

Sophia Tolstaya documented life with her husband in a series of diaries which were finally translated to English for publication in the 1980s. Her counter-novella Whose Fault? was described by The New Yorker as “a systematic rebuttal” of her husband’s work.

“I happened to have this book that I’d ordered some years ago,” Goldsworthy says. “It’s a really fascinating assortment, published by Yale University Press … of writings from the rest of the Tolstoy family, about and around The Kreutzer Sonata.”

When Goldsworthy dug into that book properly, she found out more about Sophia’s work.

“The fascinating thing about her counter-novella is that it is very much designed, I think, as a kind of repudiation.

“She had a very ambivalent relationship to Tolstoy’s text – she advocated on its behalf to the Tsar and asked that it not be censored – but I think that was a case of protesting too much. She was very fearful that people would conflate the woman in it with her, and the dysfunctional marriage in it with their marriage.

“They were not unfounded fears, because there were quite a few resemblances between what Tolstoy actually believed about marriage and sexuality, and what his deranged protagonist expresses in The Kreutzer Sonata.” Sophia Tolstaya decided to turn the tables.

“The work that she wrote, Whose Fault, is a novella about a pretty innocent young woman who marries a man who turns out to be a scoundrel.

“What’s fascinating is that, in the margin, she actually quotes from The Kreutzer Sonata in various places.

“So there are certain passages that are directly composed in retaliation to things that Tolstoy wrote.

“There’s a few elements of that which I draw on in this monologue. It’s a work of fiction and imagination, but steeped in these two texts.”

Ironically, Beethoven had originally named his sonata after a different violinist – his friend George Bridgetower, a British musician of mixed African descent – but changed it after they fell out over the treatment of a woman.

“So he scribbled his name off, and renamed it – somewhat politically – after French violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer, who never played it.”

After Kreutzer, Ayers House, March 8-11.adelaidefestival.com.au

THE RITE OF SPRING/COMMON GROUND[S]

International dance will return with The Rite of Spring/common ground[s], a collaboration

With Germany’s Pina Bausch Foundation, Senegal’s Ecole des Sables and Sadler’s Wells in the UK, featuring dancers from 14 African countries.

“Adelaide Festival is known for its relationship with Pina Bausch,” Healy says of the late German choreographer.

“We were the first Australian festival to present her in the 1980s, one of the first festivals in the world to present her as not just a new major voice in contemporary dance, but a generational game-changer.

“Salomon Bausch, her son, started a conversation with Germaine Acogny, who is known as the high priestess of contemporary dance in Africa. Both women, Pina and Germaine, had really admired each other but they hadn’t worked together.

“Contemporary African dance comes from different technical traditions to those in Germany and Europe. He wanted to explore the idea that Pina’s The Rite of Spring could be reimagined on an African body, with African dance traditions, which are as much based in spiritual connection to land and ritual as it is in the physical vocabulary.”

Similar themes of First Nations connections to Country will be explored in another Festival show, Bangarra Dance Theatre’s new work Wudjang: Not the Past.

Australian born dancer Jo Ann Endicott has been with Bausch’s company since “the very beginning” in 1973, and says this version of The Rite of Spring “is a daring project, because it’s a new adventure”.

Known in French as Le Sacre du Printemps, and set to Russian composer Igor Stravinsky’s classical ballet score, Bausch’s interpretation has been adapted to the African dancers’ distinctive senses of physicality and spirituality.

“A lot of them are hip-hoppers or street dancers or from African dance – there’s very little training like we know for ballet,” Endicott, now 72, says.

Few of the African dancers have the stretched feet that come from classical dance training.

“What is more important – to have the stretched feet, or to have this amazing want and desire to show this piece with every pore in your body? Physically and emotionally, this is the real Sacre – it’s true, it’s touching, it’s incredible,” Endicott says.

“Their background is full of tradition and ancestors … they believe also in themselves, which is perhaps their greatest attribute.”

This version of The Rite of Spring is performed in a circle of earth on the stage.

“They are so connected to the earth, to sacrifice, to rituals … it’s like reinventing Sacre, almost. These dancers are so full of passion, and with the rehearsals they ignited the piece with a new kind of energy. It’s something that you haven’t seen on stage for many, many years.”

Preparing the earth on stage is a precise process in its own right, and takes about 25 minutes.

“If the earth has the wrong consistency – which it did have just before the premiere – then it gets very dusty and you can breathe,” Endicott says.

“If it’s too wet, it’s also no good, because you slip.”

The Rite of Spring is part of a double-bill with common ground[s] – a duet by Germaine Acogny and Malou Airaudo, another founding member Bausch’s company.

It explores “how they come together as older women with different traditions, both being artists, both being the leaders of dance schools, both being very strong women with strong personalities”.

Endicott is speaking from Ludwigsburg in Germany, where she has just remounted Bausch’s work Kontakthof – the same show she performed in at the 1982 Adelaide Festival, alongside a young Meryl Tankard.

“This piece has been with me ever since it was born in 1978 – I’ve done many versions of it,” she says.

A former Australian Ballet dancer, Endicott left that company in controversial circumstances and moved to London.

“I would have given up dance completely had I not met Pina Bausch,” she says.

“In those days, the mid-1960s in the Australian Ballet company, you were kind of forced to be like the other dancers – all skinny, all looking the same.

“I was so fed up of being told that I was two or three kilos too heavy to be a dancer. But I was being told on the other side, from the wonderful choreographers and famous dancers like (Rudolf) Nureyev who came to Australia in those days, that I was very, very talented and that I was in the wrong place … that I should maybe go overseas and try my luck in Stuttgart Ballet with John Cranko. So I left.”

Diverse ages and body types were among the hallmarks of Bausch’s company, Endicott says.

“Pina’s works are so human … this inner beauty that can be connected to a dancer’s life.”

The Rite of Spring/common ground[s] is at Her Majesty’s Theatre, March 4-6.

WUDJANG: NOT THE PAST

Destruction of 46,000-year-old Aboriginal caves in the Pilbara by mining giant Rio Tinto last year provoked Bangarra Dance Theatre artistic director Stephen Page to create a work which explores what traditional links to the land mean for contemporary First Nations people.

In Wudjang: Not the Past, choreographer and co-writer Page explores the belief that culture and history are things that remain very much alive, and influence the present.

The Juukan Gorge caves in Western Australia was a heritage site where many prehistoric artefacts had been found, including a 4000-year-old belt made from human hair, which showed a direct link with the region’s Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples.

“The first thing I thought was, that poor mob sitting on Country,” Page says.

“They got sick, you know. I found out that, because of their spiritual psychology and their connection, they got punished – not the white people. They were punished by their spirit and their land, which were saying ‘You never looked after us’.

“That is the core of this story – it’s about caring for Country, the importance of that, and passing on that knowledge to the next generation.”

It was the latest in a long series of historical and sacred sites to be destroyed or desecrated by Australia’s ever-expanding resource and construction industries.

“I spent a lot of time in the Kimberley, I’ve spent a lot of time watching destruction of lands from Yolngu in northeast Arnhem Land … to Rio Tinto, BHP, I’ve seen it all. Over my 31 years (with Bangarra) and 35 works, there are at least 10 works which are dealing with the rape of the land, the destruction of land, the significance of land. How do we heal that?”

In Wudjang, Page has used his late father’s Mibinyah language for the first time.

He also returned to his Yugambeh people’s lands in southeast Queensland, home to the Hinze Dam which was built in 1976, raised 15m in 1989 and upgraded in 2011.

“I got to go back on Country with my sisters, and we got to reflect, and we’re using their language as an art form in this storytelling. One of the stories that inspired the work was when they were trying to excavate and dam in those areas, it became traumatic for the community. They were all displaced and forbidden to talk language, forbidden to carry knowledge,” 56-year-old Page says.

“Excavating has happened at a lot of different landmarks around the country – you look at mining, you look at damming, whatever the resource destruction process is.”

Wudjang is a major festivals commission for Sydney, Perth and Adelaide, co-produced with Sydney Theatre Company.

In the work, the bones of an ancestor called Wudjang are unearthed during construction of a new dam, and she longs to be reburied in the proper way. Before that can happen, she must lead a Yugambeh workman and his niece on a spiritual quest to a place of hidden significance and power.

Through this journey, Wudjang teaches a new generation how to listen, learn and carry their ancestral energy into the future.

“I was trying to find the best way to connect to a story that feels current today – that is purely about land, people, connections, the value of our kinship, and what that really means to us in this current climate,” Page says.

“This is the 21st century … over the last 20 years I’ve been observing and watching urban reconnection.

“Look at Tasmania – it took the biggest brunt, the biggest massacre ever – and look at those Palawa people, how they’ve carried that trauma in their DNA generations later, and how that shaped them as Palawa people today.

“Who are we now? What does it mean to be connected to Country? What does Welcome to Country mean? What is the significance of the spirit of the land?”

One of 12 children in the Page family, Stephen was raised in the Brisbane suburb of Mt Gravatt.

“When my dad died in 2010, he was able to talk language that I’d never heard … he was able to feel safe to pass that on to his son. David (Page’s older songman brother) took that language, and it was the first time that we were able to use our own language in composition and sonic scoring.”

Before his own death in 2016, David Page created a short work based on that language.

“That four-minute piece has always stuck with me, in that sense of David and that relationship with dad, and reconnecting. It became the seed and premise for going back on Country, looking at the language, and wanting it to be an inspiration for this production.”

Page also has fond memories of his own time as artistic director of the 2004 Adelaide Festival, which was a period of consolidation for the event after the chaotic departure of his predecessor, American theatre and opera director Peter Sellars, before the 2002 event.

“My brother (Bangarra dancer Russell) passed away in 2002 – it was during that time that I had to pick myself up and charge forward,” he says.

“Coming after Peter Sellars, he left that wonderful confusion and lots of displacement in terms of the philosophy of the Festival. It was turned on its head, and even that was a bit of an art expression.

“The one thing he did do, that I thought was really interesting, was his passion for bringing grassroots and community and Aboriginal stories to its foreground. I worked in a grassroots community – I had barely started my career – and we had to push this company into the mainstream.

“So by the time I got the offer to do Adelaide in 2004 … we knew we had to rebuild the spirit and the trust with the community, and the corporate community.”

Wudjang has been co-written with Sydney playwright Alana Valentine (who is also collaborating on the Adelaide Festival’s oratorio Watershed), and will feature text in English as well as 19 Mibinyah language poems and songs.

“It’s not a traditional script – it’s predominantly got a lot Bangarra’s choreographic form of dance, it has five singer-actors, it has four live musicians,” Page says.

“We’re calling it contemporary ceremony.”

Wudjang: Not the Past, Festival Theatre, March 15-18.adelaidefestival.com.au