Mother says daughter developed obsessive-compulsive disorder after using Kayla Itsines’ Bikini Body Guide

Following bombshell claims over the Bikini Body Guide that shot Kayla Itsines to fame, an Adelaide mother says she wrote to Itsines after her daughter’s fitness obsession turned compulsive.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

An Adelaide mother has come forward with fresh claims over Kayla Itsines’ Bikini Body Guide, saying she sent the fitness mogul a letter last year, pleading for accountability after her daughter’s obsession turned “life-threatening”

Last month, a number of young South Australian women told how the original Bikini Body Guide sparked a vicious cycle of dieting, bingeing and body obsession.

A number of other women came forward anonymously following the article’s publication, including Linda* – who says her daughter developed severe mental health issues after following the guide.

Linda contacted Itsines in 2021 over concerns with her program and the impact she believed it had on her daughter.

A response from Sweat, the parent company of the Bikini Body Guide of which Itsines is still involved, said that while they empathised with her daughter’s plight, the app “(promoted) the benefits of fitness and leading a healthy, balanced lifestyle”.

Linda told The Advertiser, for her daughter Eleanor*, the Bikini Body Guide turned into a life-changing obsession that forced her to change schools, isolated her socially and led to her seeking professional help.

Aspiring netballer Eleanor downloaded the program as a young teenager, looking for an additional fitness regime to supplement her training sessions.

“She wanted to be the best that she could be on the court and she thought this would be a good way to do it,” Linda said.

“It was purely around fitness at that point … so away she went on her quest.”

But Linda said her daughter’s relationship with the guide quickly devolved into an insatiable need to exercise.

“It became this obsessive-compulsive thing that she had to do … it got to the point where the family would go out and she wouldn’t come because she hadn’t done her exercises,” she said.

“(She perceived it as) calories-in, based on exercise out … so she felt she had to do a certain amount every day – and once she’d done that she was a different person.

“She would have breakdowns or meltdowns if it was raining because she couldn’t do her training on the courts … I would receive calls from people driving past because she was in tears.”

Linda said her daughter was forced to change schools because she “couldn’t sit down” for fear of not meeting daily exercise targets and soon became socially isolated.

“It affected everything. It affected her learning, it affected her friendship group – she couldn’t sit down at recess time, she always had to stand up. She couldn’t eat what they were all eating,” she said.

Terrified for her daughter’s safety, Linda took her to her GP, who then referred to an eating disorder specialist.

Eleanor has now been seeking treatment for two years for obsessive-compulsive disorder related to her fitness.

In March 2021, Linda sent a letter to Kayla Itsines outlining her daughter’s plight.

Linda felt the response from Sweat, seen by The Advertiser, did not acknowledge what she believed was the potential for harm.

“Members are recommended to seek advice from a relevant healthcare professional before making any changes to their diet or lifestyle,” the letter read.

“While the benefits of exercise are well-recognised, we acknowledge and continue to educate our community on the importance of a balanced lifestyle that is sustainable for the long-term.”

Kayla Itsines did not respond to The Advertiser’s request for comment.

Linda said she was just seeking “accountability” for her daughter’s experience.

“Certainly, this particular program was the main driver for this behaviour that turned into something extremely serious and possibly life-threatening,” she said.

“Whether you like it or not, these kids are going to get exposure to these kinds of apps one way or another.”

“I don’t know if (Eleanor is) ever going to be fully recovered … (I just want) some kind of acknowledgment or responsibility.”

The dark side of the Bikini Body Guide

Two weeks ago, The Advertiser revealed how a number of young women who followed Itsines’ successful ‘Bikini Body Guide’ believed it came with a physical – and mental – cost.

Itsines began posting clients’ progress shots to Instagram in 2009 – with popular iterations of the infamous ‘before and after’ images.

She soon cultivated a dedicated group of followers, known as ‘Kayla’s Army’, who shared their own epic “transformations” under the #BBG hashtag, providing visual inspiration for the effectiveness of her workout plans.

The posts soon grew into the thousands, then tens of thousands, and the ‘after’ images – which Itsines would then repost to her own profile – increasingly became synonymous with the “ideal” woman’s body.

That success paved the way for the eBooks that shot her to stardom – the Bikini Body Guide, or ‘BBG’ as it was known among her legions of fitness fans, and H.E.L.P, the ‘healthy eating & lifestyle plan’. These could be purchased together for $119.97.

The concept of the Bikini Body Guide was simple. A 12-week program involving three, 28-minute high-intensity workout sessions per week accompanied by regular movement. It was easy, accessible and promised to transform your body in just a matter of weeks.

The H.E.L.P plan outlined a week’s worth of meal ideas, often measured down to the gram, which could be mixed and matched for the duration of the program. A disclaimer on its second page assured readers it was written “with the assistance of two Accredited Practising Dietitians”.

Itsines has always maintained that her passion for fitness came from wanting to help women feel confident in their own skin. Her guide emphasised “feeling good about yourself” as a priority, rather than being “a certain body weight, size or look”.

The only calorie figure referenced in the H.E.L.P plan is 1600 as the typical requirement for “moderately active women” – which equates to 6900 kilojoules. When the H.E.L.P plan’s daily meal plan was put into the UK National Health Service’s calorie calculator, the approximate kilojoule intake sat between 5600 and 5800 per day.

According to the National Health and Medical Research Council, active girls between the ages of 16 and 20 require between 10,000 and 13,000 kilojoules per day.

The plan did allow for a cheat meal – which, according to Itsines, should only be consumed during a 30-45 minute window once per week.

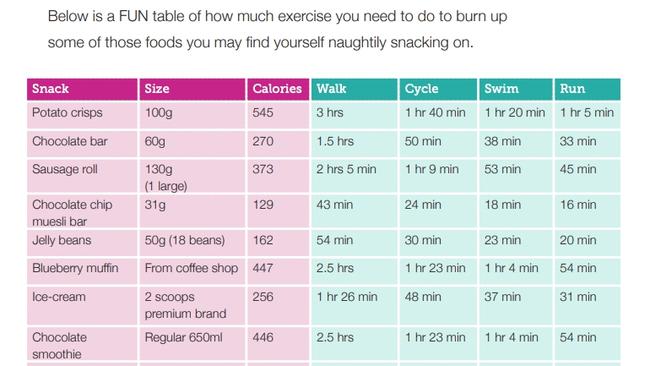

It also included a comparison chart, which told followers how much exercise they would need to do to burn off foods they were “naughtily snacking on”.

According to the Butterfly Foundation, adolescent women are at the highest risk when it comes to developing eating disorders.

The Butterfly Foundation’s Danni Rowlands, who previously worked in the fitness industry, told The Advertiser that programs like the Bikini Body Guide could be dangerous to impressionable young women.

“These platforms introduce the notion and messaging about body size being right and wrong, and that does increase vulnerability in anyone exposed to these things,” Rowlands said.

* Names have been changed by request