Young SA women speak out about the ‘negative influence’ of Kayla Itsines’ original Bikini Body Guide

Kayla Itsines’ rise from Adelaide personal trainer to global fitness mogul has been meteoric. But some young women say her initial Bikini Body Guide took a heavy toll.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

From backyard personal trainer to one of the world’s most popular fitness influencers, Kayla Itsines has enjoyed a meteoric rise to global fame.

But for some young women who were there from the start, Itsines’ successful ‘Bikini Body Guide’ came with a physical – and mental – cost.

Several young South Australian women say the Bikini Body Guide that made Itsines a social media sensation around a decade ago sparked a vicious cycle of dieting, bingeing and body obsession.

Government nutrition calculators estimate the guide’s recommended daily meal plan had an approximate kilojoule intake of 5800 – or about half the daily recommended intake for active young women aged 16-20.

Itsines has since changed her approach – her more recent platform, Sweat, steered away from weight loss-centric ideology to a more holistic view of health and fitness.

In 2021, she also renamed the Bikini Body Guide to ‘High Intensity with Kayla’, saying she regretted the phrase Bikini Body and it “represented an outdated view of health and fitness”.

“It has been almost 10 years since I created BBG with the positive intent that every body is a bikini body,” Itsines said last year.

“I’m proud that, as a company, we can look at something and think ‘that’s not good enough’ or ‘that’s not right anymore’ and make the relevant changes.”

But some women say the lessons they took from Bikini Body Guide affect them to this day.

“I would absolutely say that Kayla’s guide was the beginning of my negative relationship with my body,” 28-year-old Lily Robinson told The Advertiser.

“I think a lot of women have a very similar story of going through cycles of restriction and dieting – using the guide, then feeling like they’d burn out from doing that unachievable load.”

For Bianca Hackman, Georgie Owen and Lucy Preiss, the story is much the same.

“I remember looking at the guide and looking in the mirror and staring at all the parts of my body I didn’t like,” Hackman said.

“You were drawn to anything that will make you feel better or theoretically look better.”

According to the Butterfly Foundation, adolescent women are at the highest risk when it comes to developing eating disorders.

The Butterfly Foundation’s Danni Rowlands, who previously worked in the fitness industry, told The Advertiser that programs like the Bikini Body Guide could be dangerous to impressionable young women.

“These platforms introduce the notion and messaging about body size being right and wrong, and that does increase vulnerability in anyone exposed to these things,” Rowlands said.

Kayla Itsines did not respond to several requests for comment from The Advertiser.

HOW KAYLA GOT HER START

The 30-year-old powerhouse recently sold Sweat, the workout platform she started with former fiance Tobi Pearce, for a reported $400m. It has been downloaded more than 30 million times.

Itsines began posting clients’ progress shots to Instagram in 2009 – with popular iterations of the infamous ‘before and after’ images.

She soon cultivated a dedicated group of followers, known as ‘Kayla’s Army’, who shared their own epic “transformations” under the #BBG hashtag, providing visual inspiration for the effectiveness of her workout plans.

The posts soon grew into the thousands, then tens of thousands, and the ‘after’ images – which Itsines would then repost to her own profile – increasingly became synonymous with the “ideal” woman’s body.

That success paved the way for the eBooks that shot her to stardom – the Bikini Body Guide, or ‘BBG’ as it was known among her legions of fitness fans, and H.E.L.P, the ‘healthy eating & lifestyle plan’. These could be purchased together for $119.97.

The concept of the Bikini Body Guide was simple. A 12-week program involving three, 28-minute high-intensity workout sessions per week accompanied by regular movement. It was easy, accessible and promised to transform your body in just a matter of weeks.

The H.E.L.P plan outlined a week’s worth of meal ideas, often measured down to the gram, which could be mixed and matched for the duration of the program. A disclaimer on its second page assured readers it was written “with the assistance of two Accredited Practising Dietitians”.

Itsines has always maintained that her passion for fitness came from wanting to help women feel confident in their own skin. Her guide emphasised “feeling good about yourself” as a priority, rather than being “a certain body weight, size or look”.

The only calorie figure referenced in the H.E.L.P plan is 1600 as the typical requirement for “moderately active women” – which equates to 6900 kilojoules. When the H.E.L.P plan’s daily meal plan was put into the UK National Health Service’s calorie calculator, the approximate kilojoule intake sat between 5600 and 5800 per day.

According to the National Health and Medical Research Council, active girls between the ages of 16 and 20 require between 10,000 and 13,000 kilojoules per day.

The plan did allow for a cheat meal – which, according to Itsines, should only be consumed during a 30-45 minute window once per week.

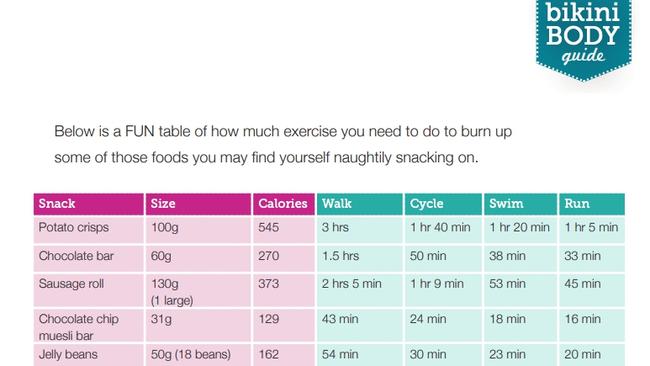

It also included a comparison chart, which told followers how much exercise they would need to do to burn off foods they were “naughtily snacking on”.

Rowlands said this transactional approach to diet could be problematic.

“Our body is functioning all the time and requires fuel every part of the day, but (comparison charts are) suggesting that by having certain things that there needs to be a compensatory act in order to make it okay,” Rowlands said.

“That really harms and disrupts a person’s relationship with eating or training.”

For the young women we profile below, the original Bikini Body craze was far from a quick-fix to a fitter, better them. Instead, it quickly spiralled into obsession.

LILY’S STORY

Before the BBG empire exploded, Lily Robinson, 28, was one of Itsines’ original backyard group training clients.

“I actually started doing group training with Kayla at her house when I was about 14 or 15,” Robinson told The Advertiser.

“A lot of Kayla’s program really talked about toning up and changing your body, so it seemed like this thing we should all be doing, we all needed to change our body and better our body.

“You’ve got the face of this Bikini Body Guide, which is Kayla, (who sold) these guides with the assumption that you’ll look like her and that is the thin ideal that you should be aiming for.”

The Bikini Body Guide had a disclaimer on its second page which reiterated that its contents were “subject to professional differences of opinion, human error in preparing this information and unique differences in individuals’ situations”.

It also reminded followers that calorie intake requirements and rate of weight loss would vary among individuals.

But for Robinson, chasing the “thin ideal” turned into a constant cycle of dieting and restriction that would last for years.

“It really started to frame food as just something associated with weight loss, instead of all the other parts of eating like that social (aspect), for feeling good or even for self-soothing,” she said.

“No one really talked about the impact of dieting and how it leads to binge eating and a negative relationship with food.”

LUCY’S STORY

For Lucy Preiss, 27, who struggled with her body image during high school, the lure of an Insta-perfect ‘bikini body’ was too strong to ignore.

“At the time all the cool girls had (the BBG),” she said.

“It got sold as such an easy thing. It wasn’t about developing a better body image or developing a healthy body or a stronger body … it was formulaic. ‘If you do X, Y and Z, in eight weeks or 12 weeks you’ll have a bikini body!’.”

Preiss also found herself following the H.E.L.P plan, which she says fed into eating-related issues that emerged in high school.

“You kind of go ‘oh well, this is what adult women do, this is how they eat, this is how they exercise’,” she said.

“But I think it gave validity to that kind of (harmful) behaviour which enabled it and encouraged it more, rather than it being a silly thing that teen girls did,” Preiss said.

BIANCA’S STORY

Bianca Hackman, 27, recalled the groundswell of bikini body obsession after graduating high school, with her group of friends desperately trying to look like the images plastered across their social media feeds.

“There was an admiration (of Kayla) at a time when your body image and the way you saw yourself was very vulnerable,” Hackman said.

Hackman said Itsines’ ‘before and after’ posts held a particular stranglehold over her body image.

“They are, to date, one of the most harmful and destructive images that feed (disordered) eating and exercise behaviours (for me),” Hackman said.

Hackman said her teenage self never questioned what she now knows was an unhealthy obsession with the Bikini Body Guide and diet plan.

“When you have a guide telling you what to do, mixed with a combination of before and after photos where everyone is smiling, they look happy and they look thin as hell, you’re going to take it as gospel and go, ‘This is what I need to do to be happy’,” Hackman said.

“I didn’t have the capacity at that point in time to go, ‘Hey, is this actually representative of what I want to achieve?’.”

GEORGIE’S STORY

Georgie Owen, 26, said the Bikini Body Guide shaped her perception of an “ideal body”.

“I remember doing the workouts and afterwards being like, ‘I’m going to have a smaller meal’, or remember going, ‘I’m not going to have a big lunch’,” she said.

“Because the messaging made it about how I looked, not about how I felt, my whole experience with that guide emphasised look, not feel.”

Owen, who now uses her own social media platform to advocate for body neutrality and acceptance, believes Itsines’ guides reinforced ‘fat-phobia’ – social stigma around larger bodies – among young women.

“If you’re constantly glorifying and idolising the smallness and thinness of bodies, that’s going to be absorbed,” she said.

“I can think of people now who are 28, 29, 30, who still have these values so deeply entrenched and are finding it so difficult to unlearn.”

While Owen herself did not follow the nutrition guide, she said she felt its “restriction” ideology ripple into the way she viewed food and nutrition.

“I had friends who were on it … when the people around you are developing a certain relationship with food, that is very contagious,” Owen said.

“It was less about tangibly following it and more about how that mindset permeates through groups of women who are already subjected to very challenging beauty and body standards.”

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

The Butterfly Foundation’s Danni Rowlands said the explosion of social media “transformation” posts and hashtag-based fitness trends was a breeding ground for body issues.

“There’s a real community around these things, particularly online, and that’s a danger,” Rowlands said.

“Celebration around (weight) loss and body shape reduction is so entrenched that the competitive dieting aspect is naturally a part of these platforms, which makes it really dangerous.”

Rowlands said before and after images were often unrealistic, or could be manipulated.

“(They) give someone a very strong visual of what could be achieved by engaging in a certain program and drive this notion that in order to be valuable, successful, attractive and loveable … we have to reduce our body size,” she said.

“It creates this suggestion that to be anything other is absolutely not OK and further reaffirms weight stigma, weight bias and entrenches that fat-phobia in so many people.”

Rowlands said the lack of regulation in the fitness industry, combined with the rise of social media ‘influencers’, was a catastrophic combination for those most vulnerable.

“People who are now in an influencing role … need to be made accountable for the messaging and information that they share,” Rowlands said.

“(Influencers and fitness professionals) need to be responsible for the fact that programs such as this can do harm.”

More than 10 years on, the young women who sought their own ‘Bikini Bodies’ have finally realised their most successful transformation. Finding joy in movement, food and their own bodies.

“I wish I could reach out to (my younger self) to tell her she doesn’t need a guide to make her worthy,” Robinson said.

“I don’t need to look like anyone else, I am me and I am enough.”