Experts issue warning over ‘what I eat in a day’ videos on TikTok

A popular trend doing the rounds on TikTok has become cause for alarm for experts and young people.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A fascination with food has exploded on Gen Z TikTok — but while that may sound innocent enough, experts warn of dire consequences.

Thousands of “What I eat in a day” videos shared by fitness influencers decked out in expensive active wear have inundated feeds in recent years, in which content creators show followers exactly what they consume for each meal.

In many instances, a “calorie-deficit” diet means it’s not much at all, yet the clips amass millions of views.

Local woman Lily Tindall, 23, recognises the unwavering grip of such content all too well, saying toxic diet culture content on social media played a dangerous role in her battle against disordered eating as a teen.

“When I was 13 to 14, I noticed that I was built a bit differently than most girls (so) I started modelling the behaviours of eating disorders like anorexia,” Ms Tindall, who is studying to become a funeral director, said.

“I was in really negative spaces online. Even on Instagram, there were forums for girls with anorexia and other eating disorders with ‘fitspo’ photos, and ‘clean eating’ diets.”

One chilling post, she recalled, highlighted an image of three water bottles labelled “breakfast, lunch and dinner”.

Fast-forward to 2024, where much of the diet-related content on TikTok is shared under the guise of inspiring “healthy but realistic” eating habits.

It’s a trend which harks back to the frightening era of Ms Tindall’s youth — when “pro-ana” (short for pro-anorexia) and “thinspo” images dotted Instagram and Tumblr blogs.

On Tumblr, pro-eating disorder content was even banned in the site’s content policy in 2012.

But while the artsy black and white aesthetic of the once-wildly popular platform left the cultural Zeitgeist years ago, the harmful diet culture content at its core has crept its way back in.

Ms Tindall — who has recovered from her disordered eating by unfollowing and breaking down habits formed on Instagram — is concerned about the re-emergence.

“I have noticed talk about the ‘heroin skinny’ trend from the 90s coming back. I was shocked and disgusted when I saw that because I thought we had moved beyond that,” she said.

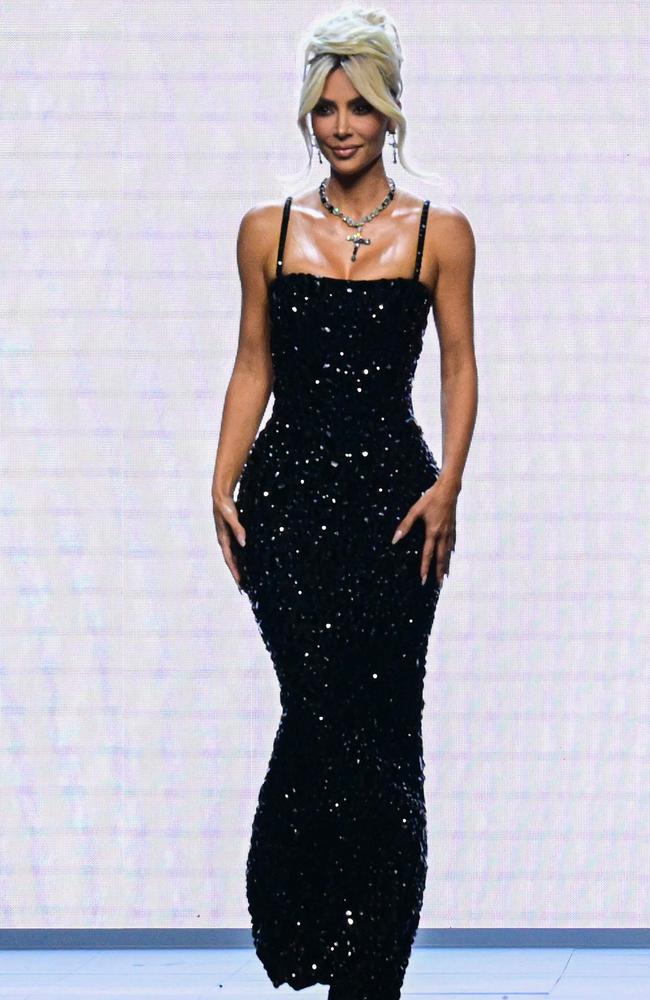

“Heroin chic” returning to the vernacular has prompted widespread panic in recent years, with Kim Kardashian’s drastic weight loss in 2022 — and a disturbing New York Post headline in response: “Bye-bye booty: Heroin chic is back” — marking the shift for many.

It seems this was just the start.

Binge dietitian and intuitive eating counsellor Erin Murnane said weight loss advice on social media had increased given the rise in conversation around Ozempic — the harmful get-skinny-quick diabetes medication beloved by celebrities.

She said meal-sharing clips were a gateway to this culture. Unfortunately, it’s a popular genre.

“Even if an influencer knows the harm of ‘What I Eat In A Day (WIEIAD)’ content, there’s no disincentive for them not to create it because it generates followers and helps them make money,” Ms Murnane explained to The Advertiser.

So how can watching random strangers on TikTok eat nothing but a green smoothie for breakfast damage your own relationship with food?

Ms Murnane said it’s down to the “comparative” nature of viral content.

“These videos perpetuate restrictive dieting, over-reliance on calorie counting, and food mortality. For example, if I eat ‘healthy’ foods, I’m good, whereas if I eat unhealthy foods, I’m bad.

“While I believe the intention of many influencers is not to cause harm, the comparative nature of social media makes it difficult for viewers to listen to their own bodies’ needs and instead follow another person’s rigid and restrictive diet.”

The Aussie dietitian said impressionable young women were particularly at risk of falling victim to such content.

“At some stage in most of these videos, influencers will also show their slim and/or toned body, sending a message that if the viewer eats what they eat, they’ll also look like them.

“This is particularly harmful for young women whose bodies are changing naturally due to puberty.

“They can develop an unrealistic idea that the food is leading them to gain weight, which is likely to lead to further food restrictions to lose or maintain their weight.”

Adelaide clinical psychologist Dr Alissa Knight said the danger lay in how quickly a scroll on TikTok can send a young person down an endless stream of ‘What I Eat in a Day’ videos, drawing them into a “psychological trance” and leading to mirrored behaviours.

“The trend really aligns with two key theories in psychology,” Dr Knight explained.

“Social cognitive theory; which emphasises the notion that people learn by observing and modelling others, and gain confidence and reassurance from it.

“And the mirror neuron system theory; which suggests people have neurons in their brain that fire more intensely when viewing another person doing a behaviour or action, and then replicating that same behaviour themself.”

Dr Knight said she was “alarmed” by the prospect of vulnerable young women or those already living with mental illness being exposed to such content.

“The TikTok algorithm has proven to be a target for those already with eating disorders, and promoting disordered eating in certain vulnerable populations to body dissatisfaction, such as teen girls and young women.

“If we think about the potential mindset of any impressionable individual watching these Tik Tok videos, especially younger females, you would expect some level of negative cognitive discourse going on: ‘Oh my gosh, I eat way too much. I am a loser. No wonder I am so fat. I am eating double what she is, and she is beautiful and everything I want to be, so I am doing it all wrong. Right, tomorrow I am on it. New diet, follow what she does exactly and it is all uphill for me’.”

Amid the avalanche of toxic diet culture content, many creators are fighting to cut through the noise, including body positivity queen Jameela Jamil who abhorred the return of heroin chic on TikTok back in 2022.

“Our bodies are not trends. F*** off,” she declared.

Earlier this year, Aussie fitness influencer Laura Henshaw, 31, weighed in, telling followers she would not be partaking in the ‘What I eat in a day’ trend.

“It is harmful. I struggled with disordered eating for two years, and I fell into the trap of consuming this type of content,” she said, pointing out that even if we all ate the same thing, our bodies would not look the same.

She said despite what these influencers told you, the content was less about food inspiration and more about “body aspiration”.

The Butterfly Foundation’s Body Kind Youth Survey found 62 per cent of young people said social media made them feel dissatisfied with their bodies — a 12 per cent jump from 2022.

Alarmingly, nearly half said body dissatisfaction had stopped them from attending school.

Body dissatisfaction is a leading risk factor in the development of an eating disorder, with Butterfly’s recent Paying the Price report revealing an 86 per cent rise in eating disorders among young people aged 10 to 19 years since 2012.

Helen Bird, Education Services Manager at Butterfly Foundation, said these

results had never been more critical.

“This is yet more evidence that young people’s body image is having a profound impact on every aspect of their lives and prevention and early intervention is critical to improve outcomes,” she said.

If you’re impacted by an eating disorder or body image concern, or know someone who is, contact Butterfly’s National Helpline on 1800 ED HOPE (1800 33 4673) via webchat or email support@butterfly.org.au Counsellors are available 7 days a week, 8am-midnight (AEDT)