SAMUEL Williams has an ignominious role in a sordid chapter of colonial South Australia. At the age of 10, he was the first boy to be sentenced to spend six years aboard a rotting sailing ship moored off Largs Bay.

Formerly the Fitzjames — which carried hundreds of British migrants to Australia in the mid-1800s — the badly leaking hulk eventually would become a floating prison holding, at any one time, more than 60 boys like young Samuel.

He was detained in March, 1877, at a reformatory school at Magill after setting fire to a farmer’s property at Sea View Hill, then a landmark south of Adelaide. Other boys would join him, mainly for theft or because, in the eyes of the law, they were homeless vagrants unable to care themselves.

The youngest was seven-year-old Edward Cavanagh who, like many of his cohorts, was officially deemed to be “uncontrollable”. Like Samuel, Edward was put in a boat, rowed out to the Fitzjames and left there until he was 16.

HEAPS GOOD HISTORY: DOWNLOAD ON ITUNES

THE HULK

The Canadian-built Fitzjames started its maritime life in 1852 as a three-masted wooden sailing ship that made four voyages from England to Australia, carrying more than 1800 immigrants. In 1866 the White Star Line vessel started leaking badly off the coast of Portugal while carrying general cargo on its fifth and final journey.

Her captain put into Lisbon for temporary repairs before setting sail again for Melbourne. Upon arrival the Fitzjames was declared unseaworthy and condemned. Her masts were removed and she was towed up the Yarra River, where she was dragged up on to the bank and left to rot.

Back in South Australia, the State Government was looking for a quarantine ship. It bought the Fitzjames in 1876 and had it towed to the Port River, where it was plugged up and fitted with an iron roof covering most of its deck.

The hulk was towed to Largs Bay and moored offshore. But — despite the state being established by free settlers rather than convicts transported from rotting naval ships on the River Thames — the incessantly leaking Fitzjames was only used temporarily to house immigrants with infectious diseases.

Instead, just like the widely condemned British floating prisons, it would spend most of its time in South Australia holding young boys and teenagers confined to a life of misery and ill-treatment on what officially would be called the Reformatory Hulk.

THE ‘ARABS’

By the mid-1870s, South Australia’s Destitute Board was struggling to control large numbers of miscreant boys roaming Adelaide, known colloquially as “Arabs”. Ranging from petty thieves to rapists, the troublesome lads were not unlike the street vagrants famously depicted by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist.

In 1880, with increasing numbers being locked up by judges and special magistrates at the board’s Boys Reformatory School at Magill, it made the controversial decision to transfer the neglected and delinquent juveniles to the Fitzjames at its mooring near the Largs Bay jetty.

Among them was young Samuel Williams, with his details the first to be recorded in The Reformatory Hulk’s official register.

The register — held by State Records SA at Cavan — contains the names of hundreds of boys ranging in age from seven to 15 who were sent by the Destitute Board to the Fitzjames between 1880 and 1891. Two-thirds had been convicted of crimes while the remainder had been determined to be “uncontrollable”.

Their individual crimes included stealing two bundles of wood, one gold ring, a beehive, 10 pigeons, three footballs, one postage stamp, 13 eggs and a gallon of gooseberries. Two boys were dispatched offshore for sleeping on the floor of a brothel operated by their parents while another teenager, aged 15, was flogged before being sent to the hulk for raping a girl aged under 13.

The boys had nothing in common except that most were homeless, had committed crimes or were not wanted by their parents. The only thing they did share was that they had been ordered by law to stay on the Fitzjames until they turned 16.

LIFE ABOARD THE HULK

A typical day aboard the Fitzjames started at 6.30am. All the boys slept on bunks in an open space beneath its dilapidated deck.

They would air their bedding, wash the top deck and do the dishes from the previous night.

Morning prayers were followed by breakfast, typically a pint of tea, currant cake and treacle.

The younger boys would then go for rudimentary reading and writing lessons while anyone aged over 13 would spend their days making boots or clothing.

The boys were given 30 minutes of exercise a day where they would run on the spot or do star jumps. The rest of the time they spent in class or in the tailoring and shoemaking workshops.

Trips ashore were rare and, with no masts or rigging to climb, there were little options for physical activity or getting sunlight and fresh air.

The most exercise the boys got was pumping water out of the hulk. The Fitzjames constantly leaked, with pumps being manned for up to three hours every day to keep it afloat. During storms and rough seas the situation got even worse, and the boys’ bedding was often soaked.

Dinner of mutton stew, soup, tea and treacle was served at 6pm. The boys would be asleep by 8pm in their communal quarters, where they were left for some years under the supervision of a known paedophile or in the company of a 15-year-old child rapist.

EXPOSING THE HULK’S FAILINGS

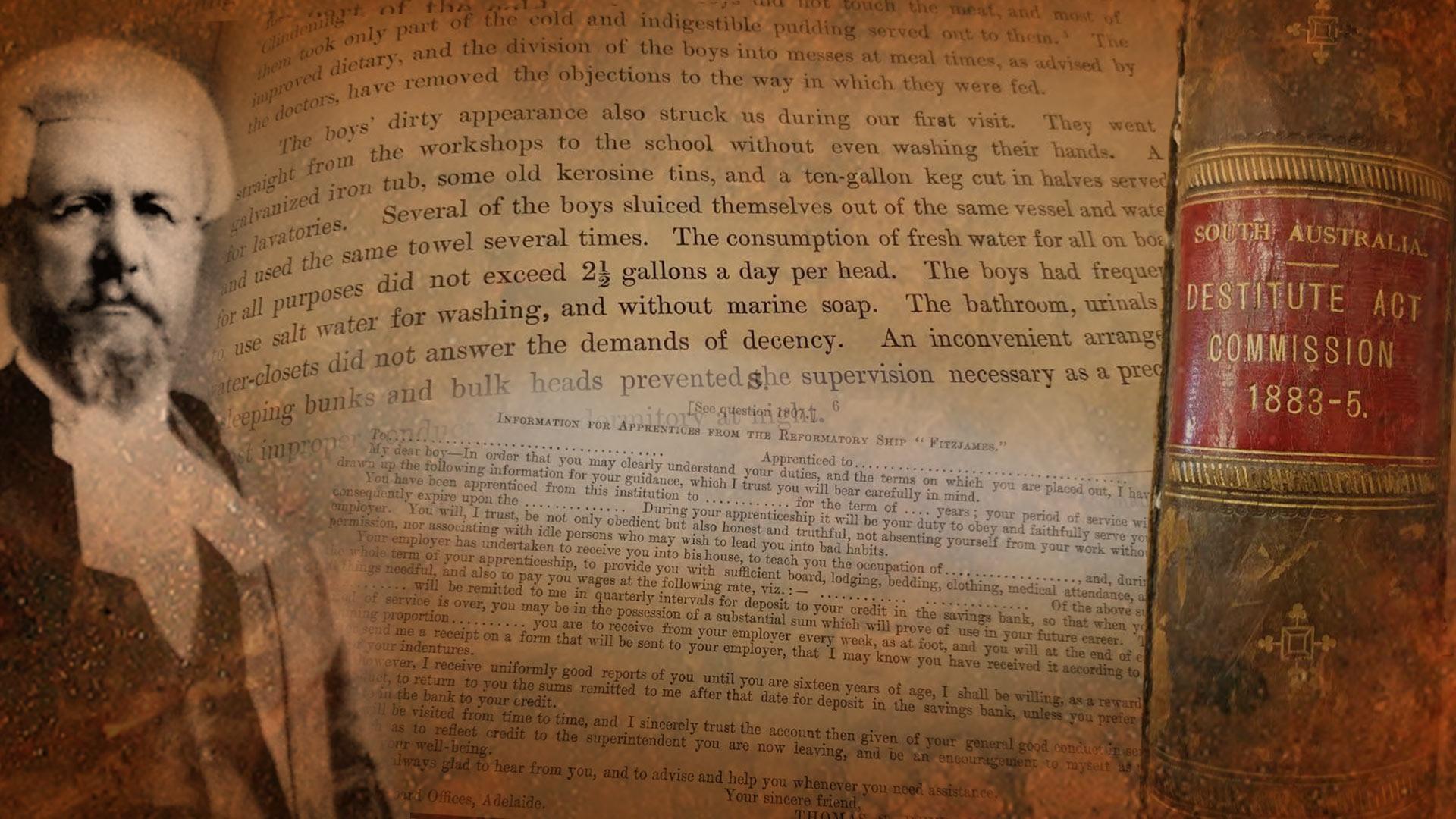

THE days of the Reformatory Hulk became numbered when a royal commission was ordered into the Destitute Board in 1883 amid concerns Roman Catholic children in state care were being neglected religiously by Protestants.

Chaired by the Chief Justice, Sir Samuel Way, the inquiry sent inspectors out to the Fitzjames to check on the welfare of the 62 boys aboard. The inspectors were struck by the “pallid and dull appearance” of the boys.

“This we attribute to the depressing conditions and wearisome monotony of the life on board, and largely to defects in the dietary and want of open-air exercise,” they wrote in their report.

“From January 1882 to the end of 1883, the boys going on shore seems to have stopped altogether, except at intervals of six or seven months.

“Since we have called attention to this matter, they have been sent on shore for cricket or football once a week.”

Education standards aboard the hulk were described as “deplorable”. When the inspectors visited they found the ship’s carpenter was taking the lessons. His predecessor had been a 14-year-old convicted of forgery.

The food also concerned the inspectors.

“On a comparison of the dietary with that of other reformatories we found that, though ample in quantity, it lacked variety and was not sufficiently nutritive. The food also was badly cooked and served.”

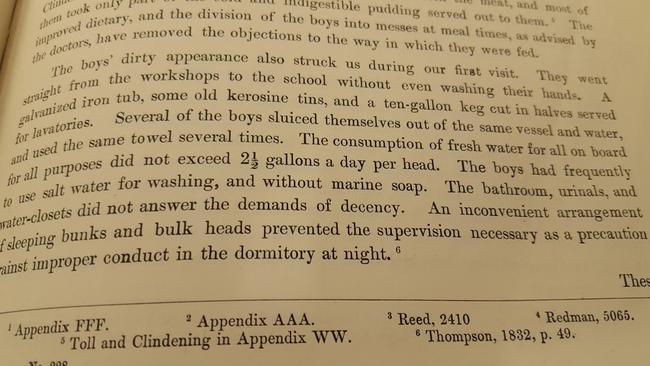

Hygiene on the ship was poor.

“A galvanised iron tub, some old kerosene tins, and a ten-gallon keg cut in halves served for lavatories. Several of the boys sluiced themselves out of the same vessel and water and used the same towel several times.”

The inspectors estimated the amount of freshwater available for each person aboard the Fitzjames was 2.5 gallons a day.

“The boys had frequently to use salt water for washing, and without marine soap. The bathrooms, urinals and water-closets did not answer the demands of decency.”

But of most concern to the inspectors was the communal quarters below decks.

“An inconvenient arrangement of sleeping bunks and bulkheads prevented the supervision necessary as a precaution against improper conduct in the dormitory at night.

“There is no separation of the more depraved boys from the others by day or night.

“They play and work together, and occupy one dormitory. There could be no effective supervision; and gross improprieties sometimes happened.

“The little runaway thief from the Industrial School, the hero of some criminal assault, the petty thief and the uncontrollable are turned, on their arrival on board, among all the other boys, without any previous isolation or study of their character, and children of eight or nine years old have their curiosity excited or gratified by the unrestrained talk of youths of fifteen or sixteen.”

Making the situation worse was the lack of supervision of the boys at night by respectable adults.

“The only night watch on board was kept by the old men from the Destitute Asylum, whose duty it was to be on deck in turn to attend to the ship’s light.

“One of the old men from the Asylum who left the Hulk in 1883 had been notorious at Port Adelaide for his immorality.

“In one case, at least, there has been the same want of care in the selection of a petty officer, as the carpenter who was dismissed in 1881 had been prosecuted for rape, and was living an openly immoral life.”

THE END OF THE HULK

THE Way Commission tabled its final report in State Parliament in 1885. The 100,000-word document was scathing in its findings about the Fitzjames, recommending its immediate closure and the transferral of the boys to a land-based facility.

“It has been costly, notwithstanding, as we have pointed out, that a mistaken economy has been practised in the items of food, teaching and superintendence,” it said.

“Although many of the boys have turned out better than might have been expected, a considerable number of them have reverted to criminal practices.

“The direct moral training, although not actually bad, has been poor and low in tone, and it has been neutralised by the indiscriminate mixing of vicious and other boys together.

“The inaccessibility of the Hulk has thrown obstacles in the way of religious teaching.

“The education of the boys has been shamefully neglected, and has been unworthy of a public institution.

“They have not been trained to suitable industrial pursuits, nor restored sufficiently early to ordinary life.

“In the one object only of providing a place of safe detention for the boys has the Fitzjames been a complete success: and this has been at the cost of immuring them in what one of the witnesses has not inappropriately designated ‘a mischievous floating prison of one cell’.”

Despite the Way Commission’s call for urgent action, it would take six more years before boys were removed from the Fitzjames. The hulk continued to leak, with the boys devoting more and more time to pumping out water. Eventually it became so unstable it was towed to False Arm on the Port River to stop it from sinking in open water.

The boys were finally removed in 1891 when they were taken to a new facility on Glen Stuart Rd, Magill — which eventually would become the site for the much-maligned Magill Youth Training Centre.

As for what was left of the ship, it was towed further along the Port River and beached near the end of Cable Company Wharf. No archaeological remains have ever been found. It is believed its rotten timber and steel sank into the mud, burying the last physical remains of a sordid — and little-known — chapter in South Australia’s history.

• The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the State Library of SA, State Records SA and SA Maritime Museum with the preparation of this article.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Lockdown Kids docu-series: Covid’s shocking legacy

Spiralling mental health, youth crime and school refusal – this must-see docu-series examines the long-term impacts of placing the nation’s children into Covid lockdowns.

While I Was Sleeping: I should be dead – these guardian angels saved me

I was hit by a car going 170km/h. I shouldn't be here. But after I was left unconscious, burning and trapped, something incredible happened, writes Advertiser journalist Ben Hyde.