‘On way xo’. It’s the same message I’d send my wife, Tania, every evening when I was leaving my work at The Advertiser.

I was standing at the lifts of level 3 of the office on Waymouth St in Adelaide after a long, honest day as deputy editor.

It was Labour Day in 2021, and with South Australia still in the grips of Covid restrictions, I’d stayed back late making some second edition changes to the next day’s paper relating to a Victoria-SA border breach in the state’s South East.

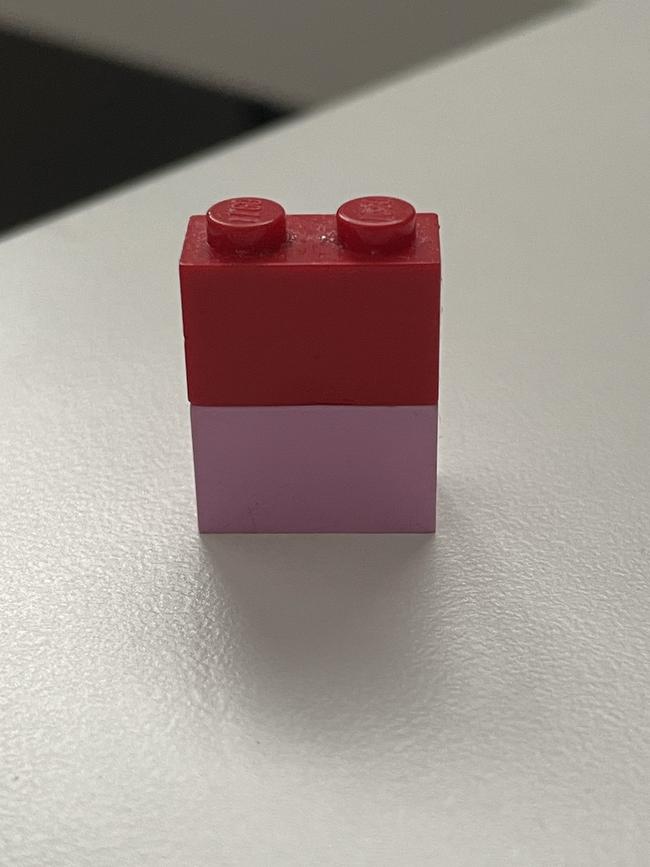

I packed up my desk and popped the little Lego creation from my eldest son Oliver, then aged five, in my pocket. Ollie’s creation was simple but sentimental – a four-block build of what he had dubbed a person to keep me safe and to remind me of him while I was at work.

I farewelled the few remaining colleagues left in the office about 10pm on a public holiday and was on my way.

Ordinarily, it would mean I’m about 10-15 minutes from returning home, walking through the front door to my loving family, giving Tania a hug and sneaking in to give Oliver and his younger brother Ari a goodnight kiss while they sleep.

Only this time, I never made it home. Not for a month at least. And sending that message is the last thing I’d remember doing for the best part of a week. That’s why I went back on a mission to find out exactly what happened, creating a documentary in the process.

Horror in the CBD

It is a blessing that I have zero recollection of what happened to me after leaving the office on October 4, 2021. But here is what we have learned over the past three years as fact.

After a troubled day, Luigi Gligora was signalled by police to pull over on West Tce, near the intersection with Currie St, on the outskirts of Adelaide’s CBD.

READ MORE:

* INCREDIBLE STORY OF SURVIVAL

With a very high concentration of prescription weight loss drug phentermine in his system, mimicking the effect of being under the influence of methamphetamine, a paranoid and suicidal Gligora refused to heed the direction of police to turn off and exit his Commodore ute.

A body-worn camera on one of the police officers who attempted to pull him over captured this exchange:

Police officer: Just stop the car. Stop.

Gligora: I can’t.

Police officer: You can. Stop the car and have a chat to me. Just stop the car, I’ll chat to you from here.

Gligora: Officer, I need an ambulance.

Police officer: I can get you an ambulance, just turn the car off.

But Gligora didn’t turn his car off. He planted his foot on the accelerator and floored it down West Tce. Investigations by SA Police Major Crash officers Jason Thiele and Alia Lyons found that the engine was working at 99 per cent of capacity as he made his way south along West Tce, hurtling through intersections towards hitting a terrifying speed of 170km/h.

As this was happening, I’d just so happened to turn on to West Tce from Grote St, as I did every evening on my journey home, totally oblivious to how my life was about to change forever.

I was driving our 1999 red Mitsubishi Lancer. It was originally Tania’s nana’s car and while not blessed with the greatest safety features, it was reliable as the day is long.

I was about 200m down the road after turning on to West Tce, outside CMI Toyota’s used car yard and travelling in the middle of the five lanes, when Gligora’s wilfully negligent behaviour culminated with him crashing into the rear of my Lancer at sickening speed.

CCTV cameras on West Tce captured the harrowing lead up, showing his ute bearing down on my car like a predator at a speed up to 110km/h faster than I was travelling.

CCTV and dashcam from the car of witness Emily Bessen, who was waiting at the West Tce/Sturt St intersection and who phoned triple-0, show an explosive fireball on impact before my crumpled car spins multiple times, crosses the median strip and comes to a rest on the other side of West Tce, on fire.

District Court Judge Nick Alexandrides summed it up when sentencing Gligora in April to four years in jail with a two-year non-parole period.

“The engine of your car was at 99 per cent of full throttle for the five seconds before the crash and your speed was 170km/h, which is simply mind-boggling,” he said.

“This is an extremely serious act of driving … there could be more serious examples, but it is difficult to imagine.”

Luckiest unlucky man ever

The ridiculously severe impact of the crash left me unconscious, trapped and helpless inside the horribly mangled and twisted metal wreck.

I was at the mercy of flames that were starting to burn my clothes and melt my skin, and smoke that was filling my airway and lungs. It may sound strange, but it was also about this time that my luck was about to change.

I had been the definition of being in the wrong place at the wrong time to be the victim of Gligora’s wanton behaviour.

But as my life closed in on me, a literal army of people swarmed towards the danger to pull my lifeless body from the burning wreck and set about reviving me.

Within no more than a minute of my car coming to rest, and with the smell of petrol prominent and risk of further explosions high, the team of guardian angels got to work.

The triple-0 call from Bessen and body-worn camera vision from an on-duty police officer at the scene is as graphic and harrowing as it is reassuring in the extreme heroism and humanity on display that night.

Bessen’s emergency phone call was made about 10.12pm, seconds after she witnessed the crash unfold in front of her, and lasted for three minutes and 45 seconds.

During the call, she effectively provides a running commentary that highlights just how fortunate I was to escape with the injuries I did. “There’s petrol, fire … under the car at the moment,” Bessen told the triple-0 call taker.

“One person trapped in the car, there’s a fire underneath it … Police have just put a fire extinguisher on it.”

Moments later, I was being pulled from the smouldering chassis.

“The police are there dragging a person out. We’ve got police cars here now and army,” Bessen recounts.

“The one that was on fire. They’ve just dragged him out. He’s unconscious. Police have got him, they’ve just got him on the road and the ambulance has arrived.”

All of that unfolded within four minutes of the crash happening. Four minutes.

The vision from the body-worn police camera is even more stark.

A handful of good Samaritans, including army personnel and off-duty police officers who just happened to be there, are literally ripping into my burning car to rescue me.

One off-duty officer who was on his way to the Hindley St police station to start his shift smashed his way through the driver’s side window and used his hands to put out flames on my chest before they reached my neck and face.

Also among the group was then-Australian Army corporal Sean Davies. He and two other army personnel were on their way to Tom’s Court Hotel in the city for their shift supervising the Covid medi-hotel. In the absence of a global pandemic, they wouldn’t have been there.

As a police officer unloads a fire extinguisher inside and underneath the car to quell the flames – while I was still trapped inside – Davies and two others pull my limp body through the driver’s side window that they smashed and bent their way through.

Davies put his army trained medical skills to work to clear my airway and start my revival by performing CPR.

SA Ambulance records, obtained through Freedom of Information, show that the ambulance with paramedic Emily George on board was on the scene by 10.17pm.

By 10.29pm, about 17 minutes after the crash, I was at the Royal Adelaide Hospital Emergency Department.

Repairing a broken body

Multiple sites of bleeding on the brain. Burns to my torso, arm and windpipe. A ruptured bladder, splenic aneurysm and damaged bowel. Fractured vertebrae, pelvis and ankle. And countless other cuts and bruises. As they’d say, injuries resembling a car crash.

The task of putting me back together again was one for the expert team at the RAH.

After a period in the ER and resuscitation, full body trauma scans and numerous tests, I was intubated, placed in a coma and taken to the Intensive Care Unit. Early the next morning I went in for surgery to repair my internal injuries and have skin grafts on my burns.

I was cut open, had my bladder sewn back together, and was stapled up again. Layers of skin from my right thigh were literally peeled from me and grafted to my right arm and right side of my torso. And I was undergoing CAT scans multiple times a day to monitor the bleeds on my brain. Thankfully, they did not require surgical intervention to relieve the pressure.

The road trauma ripple

While I was oblivious in my coma, it was my nearest and dearest closest to me who were being put through the trauma wringer that follows all the carnage on our roads.

Tania was front and centre and to this day carries mental scars as a result.

Her frantic attempts to call me when I didn’t return home that night eventually led to a police officer answering my phone, telling her I’d been in a car crash and that she had to get to the RAH as soon as possible. He could not tell her if I was alive. She left our boys asleep at home with a friend from the next street and rushed to the hospital in a wave of panic, anxiety and uncertainty.

At the hospital, she was able to see me very briefly before she was taken away and left with what felt like an eternity before knowing if I would survive. It’s not hard to see why she carries post-traumatic responses.

Oliver has battled anxiety and went through a long period of waking at night and coming to find me to ensure I was okay.

My mum temporarily relocated her life to Adelaide from Avoca Dell out of Murray Bridge. My dad was in the APY Lands for work at the time and faced a logistical nightmare to get to Adelaide. My parents-in-law raced back from the Fleurieu Peninsula after receiving Tania’s call and stayed at our place for the next month in order for everyone to get through.

That’s before you even consider the impact and toll on my brother, extended family, friends and colleagues. All this from one person’s moment of madness on our roads.

Why not me?

I spent much of my time as a young journalist –before I started my journey down the management path – as a police reporter.

I’d witnessed the scene of several fatal crashes. I’d been invited into the homes of grieving families to tell their stories about loved ones lost to the carnage on our roads.

And while I never expected to be the story, I believe that background helped to prepare me for the grim reality I was now confronted with.

I was brought out of my coma about three days later, on the Thursday, but have little to no memory of things until the weekend.

After coming out of the coma, upon the advice of hospital staff, one of the first things I had to do was come up with a pseudonym. Staff advised it was appropriate given Gligora was also in the RAH and because the crash was attracting media attention. With the help of my brother Jono, we came up with Lenny Ling.

I can only presume we had channelled the close-run second choice name for Ari and my love of the Geelong Cats and admiration for premiership captain Cameron Ling.

Some of my mates still call me Lenny today.

I apparently also had conversations regarding whether I was at fault for the crash after being told what had happened.

And also whether I was going to be okay to take some sick leave from work.

But one conversation I have no memory of in the early days after coming out of the coma was with Tania and my mother-in-law Pia.

They were in my room, after I’d been transferred out of the ICU and to a trauma ward, and discussing the sheer unluckiness of it all and why we of all people had been drawn into such a traumatic time.

While I can’t back this up given my state at the time, I’m told my response to it all were words to the effect of “why not me?”.

There’s a possibility it was the fentanyl I was on for pain relief that compelled that mindset, however I like to think it’s an attitude I’ve had towards my recovery to avoid falling into the “why me?” or “woe is me” frame of mind that could so easily have consumed me.

Living with an invisible injury

I’ve lost track of the amount of people these days who, if I knew them before the injury, say I largely come across as normal, old Ben.

Or, if I’ve met them for the first time post injury, they say they wouldn’t know.

It’s been equally one of the most reassuring and frustrating parts of my recovery.

The reality is my moderate traumatic brain injury has changed me and life forever.

Things in life that used to be done on autopilot now take far more time and effort, leaving me cognitively fatigued.

I can’t multi-task and grapple competing demands. It takes me longer to process and work through things.

I’m far more susceptible to stress and anxiety and I have a shorter fuse. I’ve had to wave goodbye to my promising professional trajectory and accept that there are things I can simply no longer do like I used to. But, as one of my dear rehab providers told me early on in my recovery, comparison is the thief of joy.

It was in the process of my resuscitation at the RAH that my burnt and tattered clothes were cut from me.

But one important possession from that night had survived the carnage: a part of the Lego man that Oliver had made for me.

Tania recalls that upon entering the ICU it was clinical, sterile and starkly white – aside from two Lego bricks from Oliver’s creation that had stayed with me. It is hard to fathom how those bricks survived the crash and the aftermath. But there we both were, a little bit broken from that night but far from beaten.

I may have been left with lifelong changes and complexities to navigate. But it’s a helluva lot better than what so easily could, or should, have been the alternative: not being here at all.

And for that, I’ll always be grateful.

Video produced by Cheng Liang and Neely Karimi

Animation and artwork by Steve Grice

Follow Ben on Instagram @bennyhyde31

ben.hyde@news.com.au

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Shock reason parents are no longer sharing pics of their kids

Parents are thinking twice before sharing photos of their children online - but what about the pictures of yesteryears? Elspeth Hussey dives in.

How old is Canadian singer Justin Bieber?

What is the atomic number of gold? What are the five main human senses? Take our weekly Brainwaves quiz – 50 mind-bending general knowledge questions.