Latest reviews: Jayson Gillham, Ensemble Q, Red Phoenix Theatre’s Festen

Read the latest reviews from The Advertiser’s arts critics, including Jayson Gillham, Ensemble Q, and Red Phoenix Theatre’s Festen

Arts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Arts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Jayson Gillham, piano

Elder Hall

May 30

Amid all the hype surrounding things new and exciting, there is something to be said for being old-fashioned.

Jayson Gillham’s piano recital was as old-fashioned as they get – it wouldn’t have been out of place a century ago or more.

Flying in the face of historical performance practice and its pursuit of authenticity, his first half consisted mostly of piano transcriptions of Bach by great names of the past like Busoni, Kempff and Petri.

Actually, this makes perfect historical sense, because these transcriptions are themselves part of the history of the reception of Bach and revealing of the time in which they were made.

Bach was represented in unadorned form by the Partita No. 1, played with clarity and precision. In Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring, a perennial favourite transcribed by Myra Hess, Gillham beautifully balanced the famous melody with the chorale theme.

A transcription by Busoni was taken at a blistering tempo, as fast as Busoni himself did, though perhaps faster than Bach imagined. But the first half was dominated by another Busoni transcription, the massive Chaconne in D minor, performed with tremendous energy and power.

The second half was a compilation of shorter works by Chopin, mostly familiar, like the Fantasie-Impromptu. But hidden amongst them was a relatively rarely heard Nocturne in E flat, an exquisite love-duet beautifully played.

Gillham ended with the Polonaise in A flat, an exhilarating performance that captured all the martial swagger and heroic tone of the music.

– Stephen Whittington

Ensemble Q

UKARIA Cultural Centre

May 29

In the visual arts, ahistorical curation – displaying works from different cultural eras aside one another – is used to draw out unexpected connections and deeper meanings within the artworks.

This term is rarely used in reference to music, but ahistorical curation is an excellent description for Ensemble Q’s Fantasias program.

The concert was a “conversation between centuries”. It wove together works from across the past 400 years; the audience was asked not to applaud until the very end to allow the diverse pieces to “mingle”.

Contrasts between movements for strings, chamber works for winds, and solo pieces also gave the program a fantastic range of colours and textures.

Ensemble Q was augmented by some exceptional young musicians from the Queensland Conservatorium. Shana Hosino’s warm tone and sensitive phrasing in the cor anglais solos for Byrd’s Ave Verum Corpus were particularly impressive.

I was sceptical about the predominance of Bruckner’s music. But Paul Dean’s excellent arrangements of Os Justi that bookended the concert gave it a cohesive narrative. The opening arrangement – for doubled bassoons, clarinets and horns, with double bass – revealed the subtlety and nuance of the movement.

The clarion counterpoint of Henry Purcell’s Fantasias for String Quartet and the ethereal sounds of Saariaho’s Dreaming Chaconne were a refreshing contrast to Bruckner’s rich harmonies.

Oboist Huw Jones gave a truly captivating performance of one of Britten’s Six Metamorphoses, while cellist Trish Dean and bassist Phoebe Russell captured the intensity of Schnittke’s Hymnus II.

Rounding out this very packed concert was Mozart’s Serenade for winds and a movement from a Kurtag string quartet.

– Melanie Walters

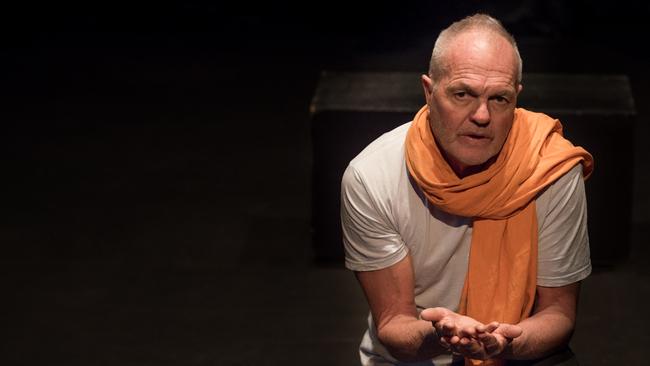

Festen

Holden Street Theatres

May 27 to June 4

Adelaide’s Red Phoenix Theatre began with a mission to present work that had not previously been performed in Adelaide. Of late, the company has refined this to focus firmly on pieces that speak to the moral and cultural climate of our time.

And so to Festen. A large and prosperous family has gathered, with a few friends, to celebrate the 60th birthday of the patriarch, Helge. The family is close-knit, for the most part, even if there are a few rough diamonds. Things seem to be going well, until an unexpected outburst from son Christian exposes a dark secret, and nothing, as they say, will ever be the same again.

To say more is to give the game away, but let it simply be said that this is an absolutely outstanding ensemble performance.

Led by a towering performance by Brant Eustice in the central role of Christian, it is a mark of the finesse of Nick Fagan’s direction that it is possible to recall something special about each and every member of the 15-strong cast.

Adrian Barnes is magnificent as Helge, smug and self-assured to the end. Lyn Wilson is coolly complicit as his dutiful wife, knowingly ignoring the reality of an unforgivable sin. Nigel Tripodi is sensational as the other son Michael, a coiled spring of anger. Claire Keene, as sister Helene, is a brittle mix of joy and sadness.

These, and others, are complemented by finely nuanced miniatures from some of Adelaide’s finest actors. Joh Hartog as the tousled, doddery grandfather, and Geoff Revel a study in drunken depression as family friend Poul — he also has one of the best lines in the piece — are joys to behold.

And there is also an unforgettable performance from Sienna Fagan, the director’s daughter, as the Little Girl. The presence of a child in this intensely charged piece adds measurably to the discomfort that everyone ought to feel.

Festen is a traumatic, high-stakes piece which, given the excellence of this production, cannot but engage. It’s a must-see.

– PETER BURDON

JOY

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Town Hall

Friday May 27 (and Saturday May 28)

Rachmaninov’s 2nd Symphony in E minor is one of the most sumptuously romantic scores to be found.

What’s more, the first question from many will likely relate to how the ASO managed the Adagio. That’s the third movement with its world-famous tune, utilized endlessly in popular music but never heard better than in its original symphonic form.

The answer is that it was magic. From principal clarinet Dean Newcomb’s transcendentally pure tones in the opening bars to the velvet richness of ASO’s lower strings and brass sections, listeners were given everything they could possibly have wanted from this core movement.

At the centre of things was conductor Dmitry Matvienko in his Australian debut. His stylish yet refined manner was perfect for this monumental score that can so easily get out of control. With one exception his depth of focus and logical interpretation prevented any excesses.

That one exception was the sheer shattering volume of such a large ensemble in a smallish Town Hall and he absolutely let rip. But on this occasion it worked, given Rachmaninov’s perfectly spaced high points.

Earlier, pianist Jayson Gillham wowed listeners in a different way during Mozart’s oh-so-clever and brilliant Piano Concerto in A, K.488. His tonal palette had rainbow breadth and there was an almost ideal meeting of mind and fingers in his lucid and sparkling performance. Furthermore, Mozart’s Adagio movement proved every bit as moving and emotionally engaging as Rachmaninov’s but with half the resources. What an enigma is music.

– RODNEY SMITH

SIX the Musical

Her Majesty’s Theatre

May 21 to June 12

“Divorced, beheaded, live!” cry the supremely talented cast of SIX, making its Adelaide premiere before a packed and wildly excited Her Majesty’s Theatre. The pop-rock musical about the wives of Henry VIII has a world-wide fan base, a lot of them in Adelaide, if the reaction of the audience was anything to go by.

Whoever would have thought that a light-n-easy student show (Toby Marlow and Lucy Moss, while swotting for their final exams at Cambridge!) put together in ten days for the Edinburgh Fringe in 2017 would since have taken the West End and Broadway by storm – and recently became the longest-running show in the history of the Sydney Opera House.

The premise is fair, if thin. Henry VIII’s six wives are arguing about who got the worst deal at the mercy of Bluff King Hal. They do so in song, and what song it is. They’re a girl band the likes of which come along once in a generation. Think Spice Girls with Beyoncé, Lily Allen, Sia, Rihanna, Britney Spears and Alicia Keys as members.

The six get their own moment in the spotlight in a non-stop 75 minutes of toe-tapping numbers that traverse rap, pop, techno, and a power ballad or two. Their distinct vocal styles blend superbly, and are brilliant underpinned by a tiny band of just four players, Ladies in Waiting, which delivers a stunning performance with a special shout-out for Kathryn Stammers on drums.

The attempts to give each of the queens a characterisation are occasionally forced and a little clichéd, especially for poor Anne of Cleves, whom history seems to regard less unattractive than her nickname of the Flanders Mare would have you believe. That said, she’s given a powerhouse performance by newcomer Kiana Daniele.

The remainder of the cast is uniformly terrific. Phoenix Jackson Mendoza (Catherine of Aragon), Kala Gare (Anne Boylen), Loren Hunter (Jane Seymour), Chelsea Dawson (Katherine Howard) and Vidya Makan (Catherine Parr) are all triple treats, singing, acting and dancing up a storm.

The dance is top notch, a triumph from Carrie-Anne Ingrouille. Each of the solo spots have their distinctive moves, from jazz through house and hip-hop, and more than a bit of ‘strike a pose’ commercial dance, and all in high heels. The ensemble pieces are sensational.

The built-in standing ovation was almost unnecessary when you’ve got 1500 people singing every word and channelling every move, and sure enough, the house was on its feet, screaming and cheering, even before the cannons showered the stalls with glittering, gleaming streamers.

SIX may not be solid gold, but it’s 18 carat plate, and a bullet-proof success at that.

– PETER BURDON

Australian String Quartet with Genevieve Lacey

UKARIA Cultural Centre

May 22

Genevieve Lacey once again showed her versatility and virtuosity at UKARIA this weekend.

Joining forces with the Australian String Quartet, the recorder player gave the premiere performance of Australian composer Lachlan Skipworth’s Quintet for Bass Recorder and Strings. This was a beautifully atmospheric work that alternated between ethereal timbres and lilting tonal material. Lacey showed brilliant tonal control and range in this work,

Elena Kats Chernin’s Reinventions showed a more nimble side to the recorder. This set of pieces – the first three of the six were performed on this occasion – are reflections on the two-part inventions of J.S.Bach. The bubbly first movement was taken at a thrillingly quick pace, with nimble playing from all five musicians.

Lacey’s rich, warm sound demonstrated the expressive capabilities of the tenor recorder in the lyrical second movement.

Given how rich and extensive the string quartet repertoire is, it is surprising just how often Beethoven’s early string quartets appear in concert programs. Nevertheless, ASQ showed an affinity with the composer’s fifth string quartet. They brought a freshness to the work with lightness in the minuet and a robust approach to the more energetic variations in the third movement.

The final work on the program was Verdi’s String Quartet in E minor. The quartet leaned into the operatic quality of this work, capturing an exceptional range of emotions.

– MELANIE WALTERS

Forces of Nature: A French Encounter

Elder Hall

May 21

Forces of Nature combined stylish historically-informed performance with innovative programming.

On a stage adorned with a mass of native flora, the Adelaide Baroque Orchestra performed a program that explored the power of the natural world through music from 17th-18th Century France and 21st Century Australia.

Opening the concert was a suite taken from Marin Marais’ opera Alcyone. Adelaide Baroque’s attention to detail in phrasing, articulation and dynamics really brought to life the imagery in this charming set of pieces, which included movements depicting fauns, shepherds, sailors and a storm.

Jean-Féry Rebel’s Le Chaos is one of the most harmonically adventurous works to come out of the French Baroque Era. Adelaide Baroque again captured the imagery of the work, with vigorous, energetic playing and really satisfying intonation in the movement’s many dissonant moments.

The French Violin by Australian composer Padma Newsome was written in response to the firestorm on New Year’s Eve of 2019. Newsome is a resident of Mallacoota, and the title refers to a 1820 violin by Nicolas Didier, in the composer’s possession at the time, that survived the fires. This highly engaging work is in five movements. The second movement combined antiphonal string pizzicato with a lyrical solo violin melody, played with warmth and nuance by Ben Dollman, while the fourth movement featured a pathos-infused solo from cellist Thomas Marlin.

The second half of the concert was a pastiche of arias and dances drawn from Baroque operas, including music by Elisabeth Jacquet, Rameau, Leclair, and Lully. Soprano Kate MacFarlane, as always, gave a beautiful and emotive performance.

– MELANIE WALTERS

Affirmation: Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

May 13

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra’s Affirmation program was a masterclass in orchestral tone colours.

Opening the concert was Respighi’s Fountains of Rome, a piece renowned for its shimmery timbres and inventive pairing of different instrumental combinations. Respighi’s idiomatic woodwind writing was highlighted in this performance, with seamless blending and dovetailing from the ASO winds.

In Affirmation, the audience was treated to not just one, but two fantastic Australian works.

Joe Chindamo’s tour de force Ligeia Concerto was given its premiere by the ASO’s own Principal Trombone Colin Prichard.

It might seem obvious to draw a comparison to the music of trombone-playing Carl Nielsen, but Chindamo clearly shares the Danish composer’s skill in weaving together disparate musical ideas into a coherent whole.

As with Respighi, Chindamo paired seemingly mismatched instruments with the trombone to great effect, particularly the use of piccolo and percussion against the warmth of the solo instrument.

The rhythmic vitality of the first movement contrasted beautifully with the lush harmonies of the second movement, and the thrilling final movement really demonstrated soloist virtuosic technique. Prichard’s vibrant articulation, detailed phrasing and tonal clarity left this reviewer hoping that the orchestra includes more brass concertos in their future programming.

Even with all the textural and stylistic variety in the first half, Lisa Illean’s Land’s End brought us to yet another sonic landscape. This beautiful and unsettling work featured slowly-evolving textures built of sustained pitch bends and gradual layering of fragile timbral effects.

Conductor Brad Cohen’s fresh approach to Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony gave the orchestral standard added vitality.

– MELANIE WALTERS

Outside Within

Australian Dance Theatre

Odeon Theatre

May 10 to 13 (regional to June 4 )

The first performance from Australian Dance Theatre under the directorship of Daniel Riley is a triple bill entitled Outside Within.

First up is a welcome repeat performance of Immerse, created by Adrienne Semmens for ADT’s Convergence program in 2021. Semmens has a longstanding fascination with water — a recent exploration is beautifully seen in a short, Underfoot, viewable online. The dancers describe the many moods of water, from gentle pools to urgent, torrential flows, and the depiction of the songlines which often follow valleys where water may be found is particularly effective.

Riley’s short film mulumna (a Wiradjuri word meaning “inside, within”), created in partnership with the Melbourne Museum and Melbourne’s RISING festival in 2021, followed without pause. Featuring Riley and his son Archie, it is filmed both in the Museum’s stores (holding an important collection of First Nations objects) and in the open air. Father and son prepare for ceremony, yet the dance is almost entirely confined to the functional, indoor space, the huge storage shelves a stage in their own right.

Riley’s new piece, The Third, flowed out of the film, and shared several design elements with it, but there the similarity ends. The movement is riveting, a whole new language for ADT, and those not familiar with Riley’s style. An intense rhythmic awareness is coupled with a feel for shape, both individual and group, and line, whether straight or angled. It makes for exciting watching.

After a short season in Adelaide, the program hits the regions for a few weeks. It deserves to be widely seen.

– PETER BURDON

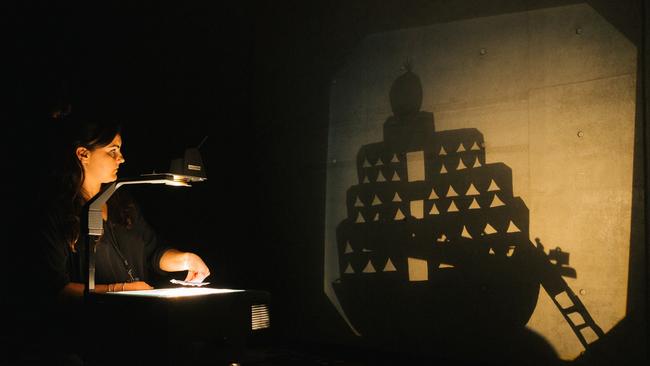

Cathedral

The Space Theatre

State Theatre Company

This is death in the cathedral. Deep in the waters of the Naracoorte caves a diver is dying.

His life flashes before his eyes and this gives Caleb Lewis, the playwright and Nathan O’Keefe, the actor the chance to create a complex and compelling tale. Breathless and breathtaking in its ambition, it is a superb achievement.

The diver’s name is Clay. His stillborn twin was Moss. Lewis calls the water amniotic. Already something mythical, biblical indeed, in unfolding. Clay’s mother’s disappearance, and his Pop taking over his upbringing, have shaped his life and led him to the extremely hazardous career as a deep sea diver in the North Sea.

We follow that journey with him, incident by incident, from Bali to Scotland and home again, as O’Keefe prepares to deliver the last twenty minutes or so as a radiant and poignant farewell.

Director Shannon Rush has helped O’Keefe to bring the tale with simplicity and attention to a rapt Space audience. While it’s a monologue, eight Adelaide voice actors can be heard commenting and conversing, an inspirational idea.

O’Keefe’s sturdy physicality, in the classic simplicity of a black diver’s wetsuit, is an ideal combination of strength and vulnerability, appearing and vanishing in Mark Oakley’s lighting. Warning are posted at the door about loud noises in Andrew Howard’s soundscape. Terrific thunder, and anti-aircraft fire boom through the Space. Set and costume are the work of Kathryn Sproul, giving the action a versatile and yet uncluttered platform.

– EWART SHAW

Friends! The Musical Parody

Dunstan Playhouse

May 8 (season to May 15)

It’s a mark of the enduring popularity of the US sitcom Friends that 18 years after it ended, it retains its legions of fans all over the world.

Including in Adelaide, if the crowd at Friends! The Musical Parody, finally making its pandemic-delayed Australian debut, is anything to go by.

The creators have cherrypicked some favourite themes and stories from the 10-year run. There’s Joey’s rocky acting career, Chandler’s rocky love-life, and Phoebe’s dreadful singing. Famous episodes, too, like Joey’s handbag, Monica and Tom Selleck, and the flashbacks to past Thanksgiving dinners.

All these are punctuated by the occasional appearance of the perpetually annoying Janice (in full drama-queen mode) and Joey’s chain-smoking agent Estelle.

A really likeable seven-strong ensemble brings these characters to life in an all-singing, all-moving, non-stop 90 minutes of fun.

Quite how it would work with the show’s creators firmly rebuffing any attempt to use the iconic original music was anyone’s guess.

Composer Assaf Gleinzer has ingeniously taken instantly recognisable snippets, both tunes and rhythms, in extracts just short enough to avoid breaching copyright.

That said, he’s at his best when he does things straight: the Central Perk Tango (a great take on Cell Block Tango from Chicago) is genius.

Some of the tropes are dated, a generation on – the lazy gay jokes, cultural stereotyping, and the fat-shaming of Monica’s heavier days – but Friends is of its era, and the parody is an American creation!

Like its celebrated namesake, Friends! The Musical Parody is wafer thin, fiction and fantasy, part of life’s “insubstantial pageant”, and it’s a resounding success.

– PETER BURDON

The Love Sermon

Clementine Ford and Libby O’Donovan

Woodville Town Hall

May 8

This performance, perfectly timed for Mother’s Day, was ecumenical in scope and secular in depth.

Writer, broadcaster feminist Clementine Ford delivered her thoughts to a receptive congregation who filled the Woodville Town Hall.

She’s an evangelist for that overlooked love, self love, the love you give yourself from which you can support and love others. She’s witty and perceptive.

For this event she decided to bring on some music, and who better than the wonderful Libby O’Donovan to provide that. Both of O’Donovan’s parents are Anglican priests.

Her songs were not out of the hymnbook, but more the Broadway songbook. They included Sondheim’s Children Will Listen and a touching song from Sarah Bareilles’ Waitress, She Used to Be Mine. They received a standing ovation.

The show is part of a new seasonal development at the Woodville Town Hall.

It was opened by Katrina Power with a highly charged welcome, loudly applauded.

– EWART SHAW

Soul Serenade – The Aretha Legacy

Charmaine Jones and the GOSPO Collective

Seasonal Sessions

Woodville Town Hall

May 7

Last month Adelaide’s Charmaine Jones was a backing vocalist for Robbie Williams at his Melbourne shows.

That’s brilliant, but Jones deserves the spotlight to herself. Why she isn’t already a major star on the national stage, I don’t know.

Perhaps it is because it isn’t all about her; sharing the limelight with the GOSPO Collective and her vocal students, here and interstate, is her passion.

Woodville Town Hall was the perfect setting for Soul Serenade – The Aretha Legacy.

Seated at tables in a cabaret-style setting, the audience felt intimately connected to Jones from the first note of her opening song, Amazing Grace, which began a cappella.

The repertoire included Son of a Preacher Man, Chain of Fools, I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You) and a mash-up – which Gospo does so well – of Think and Respect.

Jones isn’t trying to be a tribute act. Through songs and storytelling, she is paying tribute to the extraordinary life and legacy of Aretha Franklin. And she does it so beautifully, with warmth and sincerity.

She also shares chapters of her own story, as she explains what this music and the GOSPO Collective community mean to her.

Jones makes each song her own. Her vocals on the lesser known Day Dreaming are sublime and her take on Ain’t No Way sends shivers down the spine.

Backing vocalists, Joanna Arul Tropeano, Ellen Walsh and Angus Arthur, the GOSPO jazz band and choir, are all superb.

Other show highlights include I Say a Little Prayer and an audience singalong on Franklin’s 1987 hit duet with George Michael, I Knew You Were Waiting (for Me), along with what was to be the final number, the sensational, (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.

When the audience demanded an encore, Jones and co. returned to the stage – admitting they didn’t have anything prepared – and launched into an impromptu upbeat blues number.

Jones can scat with the best of them. Respect.

– ANNA VLACH

A Streetcar Named Desire

Bakehouse Theatre Company

Bakehouse Theatre

This wrenching production of the Tennessee Williams classic, rooted securely in Greek tragedy, is as mesmerising as a carcrash. We witness and can do nothing. Director Michael Baldwin knows when to let his actors have their heads. A door is leftajar. Brendan Fitzgerald’s playing can be heard. This is New Orleans, after all, home of music and natural disasters. StephenDean fills the space with evocative light and sound. The play’s the thing.

Blanche Dubois has lost her home, her husband and her mind. She embodies the virgin/whore dichotomy. Carried by desire shearrives at the Elysian Fields, home of heroes. Her sister Stella welcomes her but there’s a monster in those fields Stanley Kowalski, ex army, working class and a casual rapist. Melanie Munt goes beyond the cliches of the faded southern belle ina pitch perfect incarnation. Paul Westbrook, insolently muscular, stalks her like a beast. He sweats sexuality and can howl ‘Stella’ to wake the dead.

Around this couple, the others male and female accommodate themselves. Justina Ward is a sympathetic Stella, accepting herhusbands violent rages for the lovemaking that follows. Upstairs,

Susan Cilento as Eunice has a much better, though frequently volcanic, relation with Steve, Nathan Brown. Into this worldwanders a young man, Matthew Adams, totally bewildered as Blanche’s potential prey. Marc Clement is Mitch, tender, caring, who falls for Blanche and is the saddest victim of her delusions.

Magically the doctor and nurse who come to take Blanche into asylum are played by Peter Green and Pamela Munt. They have guardedthe Bakehouse for over twenty years. They lead the tragic heroine out of the building, as if leading the theatre of emotionand illusion to another home.

– EWART SHAW

Voss

State Opera of South Australia

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Festival Theatre

May 7

Such a joy, such a privilege to experience Voss again after so many years. It was immediate and visceral, outstanding in imagination and execution.

The semi staging meant the cast was not singing across the gulf of the pit. It meant that every note sounded clear, every word hit home and every evocative gesture of conductor Richard Mills could be seen. Every sure response from the Adelaide Symhony Orchestra could be witnessed.

Samuel Dundas was charismatic as the title character, heroic, stubborn and superbly sung. Laura Trevelyan as embodied by Emma Pearson sang with lustrous effect, as his spiritual partner and guide.

The expedition party is strongly cast. Joshua Rowe is artist Palfreyman, Michael Petrucelli is Lemesurier and Nicholas Jones is Harry Robarts, an orphan desperate to be needed.

As Voss assembles his team, Sydney society clusters about him. Lieutenant Tom Radclyffe, Mark Oates and Belle Bonner, Jessica Dean embody traditional romance, dancing lightly. Belle’s parents Pelham Andrews and Cherie Boogaart sponsor the expedition but Mrs Bonner can already see that Voss is totally adrift. He is lost, lost already. His eyes cannot find their way.

Andrews and Boogaart return in the second act as Judd and Mrs Judd. Judd and his two indigenous workers, Dugald, Trevor Jameson and Jacky, Elijah Valadian join the expedition. As everything falls apart Voss ‘ madness becomes unmistakeable. Judd leaves him. Michael Petrucelli’s mad scene and suicide, brilliantly done, is followed by sheer pathos as Harry Robarts dies in Voss’ arms. Nicholas Jones is heartbreaking. The two indigenous characters becomes the land’s revenge. Dugald destroys Voss’ letter to Laura and Jacky cuts his throat with the knife Voss gave him on first meeting. The first class calibre of the cast extends to Rachel McCall as the maid Rose, Jeremy Tatchell’s reporter and Jiacheng Ding as Mr Topp. Anthony Hunt’s chorus are strong and articulate.

Stuart Maunder, director of this and The Turn of the Screw is an immensely practical man of the theatre. The elegance of colonial Sydney and the desolation of the desert flowed backwards and forwards across the narrow platform. With the world class design team of Roger Kirk and Trudy Dalgleish augmented by Jamie Clennett’s video design, this production in no way short-changed, audience, cast, orchestra or opera.

Voss brought together Patrick White’s novel, David Malouf’s libretto and Richard Meale’s music. When it premiered it was touted as the great Australian opera. Well, let’s have more operas, Australian in story and in telling. Then let history judge.

– EWART SHAW

The Turn of the Screw

State Opera of South Australia

Festival Theatre

April 30 (also May 4 and 6)

State Opera’s new production of Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw is a flat-out triumph. The casting, the music, the design, the lighting, they all come seamlessly together in a memorable and deeply moving production.

Like much of Britten’s operatic work, the story is hardly promising. A young, inexperienced governess arrives at a country estate, only to find herself in a pitched battle to protect the children under her charge from corruption by malign forces. It’s a psychologically-charged battle between good and evil.

That said, a fine libretto from Myfanwy Piper and Britten’s astonishing music make for a firm foundation. But it all depends on the cast.

And what a cast it is. State Opera Artistic Director Stuart Maunder has amassed a top shelf ensemble. Rachelle Durkin is commanding as the Governess, strong and clear and intensely emotional, running the gamut from joy in meeting her charges, Flora and Miles, mounting concern for their welfare, fear as things spiral out of control, to determination to save the children, come what may.

The bedrock of the house in which the opera is set is the housekeeper, Mrs Grose, and Elizabeth Campbell completely inhabits the role. From the moment she comes on stage, she commands respect and attention, her voice a magnificent instrument, filling the vast space with ease. She also gives the character a particular gentleness and love for the children.

The children – ah, what troublesome roles. Many is the director who’s cursed Britten for writing such wonderful, but fiendishly difficult, parts for children. Both Eliza Brill Reed (Flora) and Max Junge (Miles) give performances of great musical accomplishment, and like dramatic impact. Their interactions with the ghosts of the past governess, Miss Jessel, and the master’s valet, Peter Quint, are both effective and chilling.

Speaking of ghosts, it is one of the many strokes of genius in this opera that Miss Jessel and Peter Quint are not only visible, but audible. Their very presence, whether faintly in the background or looming large, charges the atmosphere, and both are quite superbly executed by Kanen Breen and Fiona McArdle.

Breen has a voice tailor-made for Britten, supple and incisive, while McArdle is every bit the match for a hugely experienced cast.

Roger Kirk’s set is a masterpiece, towering walls that are a dramatic element in themselves, and costuming in black, white and grey that accentuates the bleakness of the tale. Trudy Dalgleish’s lighting, too, is well judged.

And so to the music. State Opera Head of Music Anthony Hunt had the cream of the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra for the 14-strong band ready to roll until yet another of those pesky pandemic-related issues threw a spanner in the works. Fortunately – very fortunately indeed – renowned Britten specialist Paul Kildea, half a world away, jumped on a plane, and not too many days later conducts an inspired performance of one of Britten’s most extraordinary scores, full of exotic and atmospheric sounds.

Britten’s music is not easy. And The Turn of the Screw is a disturbing tale, particularly the enigmas that swirl around the relationships between the children and the ghosts, especially Miles and Quint. But my goodness, it’s worth the effort. This is as good a piece as State Opera has done for years.

-PETER BURDON

Van Diemen’s Band

Musica Viva

Town Hall

April 28

Described by their director, Baroque violinist Julia Fredersdorff, as “a little Tassie band”, Van Diemen’s Band is much more than that.

Its six players, five string performers plus harpsichordist, provided a really engaging program that pushed the boundaries normally encountered with Baroque specialist instrumentalists.

In particular, their harpsichordist Donald Nicolson’s newly minted composition Spirals, especially written for the group and in one of its world premiere performances, essentially used their Baroque instruments, plus remnants of Baroque forms in a completely new way involving 21st century musical language. The result was absolutely entrancing, as the groups soundscape – inevitably gentle and dialled-down in comparison with modern norms – flitted, floated and flirted with astringent harmonies, angular melodic constructs, and rhythmic irregularities. The effect was like meeting familiar friends in strange surroundings.

The same happened with Maria Huld Markan Sigfusdotir’s Clockworking (2013) that pitted Baroque instruments against a gentle backing track producing a very persuasive sonic melange, familiar yet original.

All this beautifully illustrated the program’s theme of Borders, its plangent congruence with current developments in Europe adding to its original more Covid-driven focus.

You could have heard a pin drop during 2nd violin Simone Slattery’ evocative recorder solos at the end of Spiral, with their deliberate references to Ukrainian music.

Top of the group’s other items was an anonymous 17th century work, Sonata Jucunda, that contained passages worthy of Bartok. This was an extraordinary piece, redefining borders in the artistic sense.

– RODNEY SMITH

Seagull – Independent Theatre

Little Theatre

April 22–30

Independent Theatre launches its 2022 season with a production of Chekhov’s Seagull in a striking new translation that breathes new life into the 1895 classic.

Seagull is about love, particularly the unrequited type, but also false or feigned love, and misguided or misplaced love as well.

The central character is a young writer, Konstantin, torn between the irresistible urge to write and to create, and his desperate desire for affection from his vain and overbearing mother, Arkadina, and a shy young actress, Nina.

As Konstantin, Independent regular Eddie Sims gives a really good performance. He is completely invested in the character, anxious and emotionally vulnerable, yet utterly convinced of his vocation as an artist.

His mother, Arkadina, is given a searing performance by Rebecca Kemp, lavishing scorn and contempt upon her son, extending arms of affection only when it suits, or serves her purposes.

The young Nina is well done by Eloise Quinn-Valentine, eager yet uncertain at first, then growing apace in maturity and wisdom.

There is also a fine performance as the family friend and doctor Dorn from Adam Goodburn, usually associated with local operatic pursuits, and very good in his first straight theatre role.

Elsewhere, the performances are impressive, but uneven. As the manipulative farm manager Shamraev, Leighton Vogt is far too dominant, while Kate van der Horst overplays his depressed, self-loathing daughter Masha (herself in love with Konstantin) as a brittle drunk rather than a tragic character. Patrick Marlin underplays the cool detachment of the novelist Trigorin.

A few of the really key symbols in the play go for little. The lake on the country estate where the action all takes place, for instance. And especially the dead seagull, once joyous and free yet able to be destroyed, a portent of Konstantin’s own death and Trigorin’s destruction of Nina’s career.

That said, it’s a solid production, well worth the effort.

– PETER BURDON

Vincent in Brixton

St Jude’s Players

St Jude’s, Brighton

April 21-30

We know that the celebrated Vincent van Gogh spent a few years in London in his early 20s. Quite what he got up to is anyone’s guess, and Nicholas Wright’s Vincent in Brixton takes a dark if speculative stab at what might have been.

A young and painfully naive Vincent happens upon a south London house, attracted first by the pretty daughter of the house but in time — gasp — with her widowed mother. In Geoff Brittain’s production, it is this older character, still bowed down with grief many years after the death of her husband, who is the star of the show.

As the sorrowing Ursula, Nicole Rutty gives a standout performance, brim-full of emotional tension. When her sorrow turns to joy, and she casts off the widow’s weeds for a dress of spring flowers, she is transformed, yet when the flighty Vincent runs away, her regression is truly tragic.

But it would not be possible without Vincent, and Alexander Whitrow is highly impressive in his stage debut in a leading role. Naive, yes, but not without guile, and we’re left in little doubt that the mental illness that wracked this great artist’s life was ever-present on his journey.

The minor characters are nicely done, though Vincent’s sister Anna (an intense account by Gabrielle Douglas) is played too spitefully — surely not intended in a person whose motives were driven by personal piety. This was cruelty, with no intent of kindness.

The ever-estimable St Jude’s players is off to a decent start in 2022 with this solid production.

– PETER BURDON

Classics Unwrapped 1: Unreel

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

April 20

The Adelaide Symphony Orchestra’s popular Classics Unwrapped concerts are a firm favourite across the breadth of the orchestra’s fans, from old to young. The clever themes devised in partnership with regular conductor Guy Noble are key to their success.

Music for the big screen is an obvious enough choice, and the choice of composers was judicious indeed. The classics were uniformly well-worn – one Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra and another Strauss’s Blue Danube (2001: A Space Odyssey), Barber’s Adagio for Strings (Platoon); and a couple of Morricone pieces (kudos to oboist Renae Stavely in ‘Gabriel’s Oboe’ from The Mission).

Australian composers were happily represented, beginning with Jamie Goldsmith’s atmospheric Pudnanthi Padninthi II for the Welcome to Country. Nigel Butterly’s Concert Suite (Babe) is a gem, the theme from Saint-Saëns ‘Organ’ symphony ringing around the Town Hall (and hummed enthusiastically). A surprise was a short piece from Sydney composer Jessica Wells, drawn from her score for a 2004 short film, Butterfly Man. A delightful piece, it’ll see plenty of traffic on Vimeo as people look it up!

A soloist is a rarity in these concerts, and who better than Adelaide’s own Konstantin Shamray, who gave a sublime performance of the slow movement of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto, and a flashy account of Richard Addinsell’s brash Warsaw Concerto from the 1941 film Dangerous Moonlight. The theme of this neglected piece (“a cheaper version of Rachmaninov,” to quote the conductor) is terrifically hummable: no surprise, considering it sold 3 million copies in its day.

Rarer still is a guest conductor whose job is not conducting. It was the experience of a lifetime for loyal patron Sally Gordon, whose vanquished all bidders at a fundraiser for a chance to conduct her beloved ASO. Prospective benefactors please note.

The concert marked the retirement after 32 years of Principal 1st Violin – and Acting Associate Concertmaster of late – Shirin Lim. A generous tribute from Noble, and hearty applause from the audience, was capped by a standing ovation from the entire orchestra as she left the stage for the last time. Very touching it was.

– PETER BURDON

Jubilation: Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

April 8

The renewal of interest in Clara Schumann’s music in recent years is well overdue.

Schumann, described as a renaissance woman in the New York Times, was well-known for her virtuosic pianism. As a composer, her oeuvre consists mostly of piano miniatures; her Piano Concerto in A minor is, unfortunately, the only completed large-scale work in her catalogue.

It was premiered with the composer as soloist when she was only sixteen, but there is nothing juvenile about the concerto’s musical language. It combines the expressivity of early Romanticism with the sparkling energy of late Classicism.

Andrea Lam, the soloist joining the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra for this performance, was exceptionally engaging, Her playing demonstrated a deep understanding of Schumann’s music, and her eloquent phrasing was particularly effective in the mostly-unaccompanied Romanze movement

Schumann’s Romance in A minor was an excellently chosen encore, with its melancholy lyricism showing a more subtle side to Schumann’s later music. Lam drew out the piece’s pathos with sensitive phrasing.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 is renowned for its massive soundscape, but it was the softer moments that stole the show in this performance. Under the direction of conductor Eivind Aadland, the Adagietto began with exquisitely ethereal timbre from the strings.

Trumpeter David Khafagi really captured the tension of the opening funeral march, while Adrian Uren played the horn solos in the third movement with excellent control and a powerful tone.

Also included in the program was Mozart’s Overture from The Marriage of Figaro. While the orchestra performed it well, it was perhaps an unnecessary inclusion in an already-expansive concert program.

–MELANIE WALTERS

Exposed

Space Theatre

April 6 to 9

Much great art emerges from adversity. For Restless Dance Theatre artistic director Michelle Ryan, whose active embrace of her own disability has driven her to create truly inspirational work, a chance reminder of her own vulnerability was the impetus for “Exposed”.

A gleaming silver curtain hangs before the audience. Obviously it’s going to rise, or fall, but no, as the house lights dim, it becomes magically transparent. Behind this gossamer film we see the dancers – near naked, literally exposed – slowly dressing themselves, a metaphor for protection, or possibly defence.

And so begins a journey that explores the desire – the right – to be independent and the plain fact of life that at some time, everyone needs the support of another.

There are some electrifying moments. At the very beginning, there are silent cries of anguish, writhing in pain, and especially a scene when the petite Darcy Carpenter finds herself surrounded by strong men, all a good foot taller than her. This is vulnerability writ large.

At other times there are splendid revels, with Charlie Wilkins in particular exuding joy.

Underpinned by an exquisite score from Hilary Kleinig and Emily Tulloch, and a design from Geoff Cobham that is extraordinary even by his high standards, Ryan has crafted a really fine piece.

It’s been widely observed that in the last couple of years, Restless has embraced a fully professional model of training and rehearsal, and the benefits are there for all to see. The transitions from ensemble to solo and small group are seamless, while the movement of the individual dancers, especially laterally, off-centre and – always a risk -off balance, is exemplary.

Restless is fast forging an international reputation as a leading creator of dance by and for performers with and without disability. Works like their new “Exposed” demonstrate why this is the case.

– PETER BURDON

Last Night of the Proms

Festival Theatre

April 1 and 2

There won’t be many people in Commonwealth who haven’t at least heard of the Last Night of the Proms, the classical knees-up that concludes the BBC’s summer music season.

Orchestras throughout the empire program their own version of this patriotic love-fest.

The Adelaide Symphony Orchestra is no exception, invariably under the baton of Guy Noble.

There are a whole lot of traditions, and traditional music, associated with the Last Night, not the least of which is a vocal soloist, there to give of their best. Soprano Desiree Frahn gave Czárdás from Die Fledermaus (where the singer pretends to be a Hungarian countess!) and the ravishing O mio babbino caro from Gianni Schicchi.

The selection of such contrasting pieces made for a great showcase of one of our best operatic voices.

The Last Night invariably features an unusual bit of programming, and there were a couple of welcome guests in the form of the last movement of Peggy Glanville-Hicks’s Sinfonia da Pacifica and the overture from Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers.

The former is a fascinating piece, influenced not so much by the pacific but the subcontinent, with pulsing drums and hints of the exotic east.

The overture is a striking work, multi-layered and textured, and redolent of the wind-swept Cornish coast.

The second half often includes Wood’s Fantasia on British Sea Songs, with the Hornpipe punctuated by hooters, whistles and notably poor rhythm. The Adelaide audience lived down to expectations.

Likewise, Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 is to include humming and the singing of Land of Hope and Glory. Unfortunately the locals didn’t get the memo about the humming, but there you go.

Jerusalem gets its annual outing. At least they gave Rule, Britannia a miss.

These concerts are a bit of fun, and the ASO and guest organist Peter Kelsall played wonderfully, even with the last minute Covid-related loss of the entire chorus and the harpist – the latter artfully substituted by pianist Michael Ierace.

That said, they’re fast getting towards their use-by date. A few flaccid Union Jacks and a few streamers don’t cut the mustard.

– PETER BURDON

Constellations

Bakehouse Theatre

Until April 9

Constellations, a cerebral romance from British playwright Nick Payne, receiving its SA premiere in a snappy production from STARC Theatre.

Roland (Marc Clement) and Marianne (Stefanie Rossi) meet, fall in love, live their lives, with ups and downs, an, inevitably, death.

It’s a slight and well-worn premise, but Payne’s brilliant writing makes it sparkle.

The endless possibilities of their lives and relationship are given full flight in a rapid-fire sequence of 50 or so short scenes, where the same or similar words return again and again with constantly shifting emotional pitch and yaw.

On the surface, the characters could hardly be less alike. Roland is a beekeeper, Marianne a quantum physicist. He seems to have lapsed into his career, her’s has been a calculated, straight line. (That said, Aristotle wrote about both beekeeping and physics as models of interactivity, so perhaps not.)

As Roland, Clement is a charmer and a conciliator. As for Marianne, when her cool equilibrium is upset by something inherently unstable – the sudden onset of terminal illness – her desperation is barely controlled.

Rossi gives an explosive performance in this often searing role.

The to-and-fro of the play is given ample assistance by the clever set design, a ping-pong court and table affair where force and effect are brought into sharp relief as one version of the same words impacts on the interaction between the two.

Tony Knight directs the action with his customary light hand.

Constellations is a reminder that relationships are an infinity of component parts, that can go in any direction, sometimes unpredictably. Until death.

– PETER BURDON

Guess How Much I Love You

Dunstan Playhouse

Until December 21

Playwright Richard Tulloch’s adaptations of children’s books are things of beauty, perhaps none more so than his version of Sam McBratney’s enormously popular Guess How Much I Love You books.

There aren’t many parents of children under 5 who don’t know the story of a couple of brown hares, parent and child, whose affectionate banter about just how much it’s possible to love has made the books compulsory bed-time reading for a generation now, and more.

The success of any venture of this kind is to be found in the audience. Tots from just 3 or 4 years of age were along, many in a theatre for the first time, and the noise was deafening. But as the house lights went down, and Isla Shaw’s design was revealed in all its watercolour beauty, and the house fell silent.

“I love you THIS much!” cries Little Nut Brown Hare (Catherine McNamara), stretching her little paws wide. “And I love you THIS much!” says Big Nut Brown Hare (Drew Wilson) in reply, holding grown-up hands much further apart. Little Nut Brown Hare’s determination to be just as big is an important part of the story.

There’s a gentle sub-plot about nature and the changing seasons, but what matters is that Guess How Much I Love You is long on wonder. It kept the ankle biters engaged for a full 50 minutes, and that’s worth the price of any ticket!

— PETER BURDON

Andrew Blanch and Emily Granger

Ukaria Cultural Centre

December 12

There’s very little written for acoustic guitar and concert harp to play together so perhaps composers have considered it an unpromising mix.

But harpist Emily Granger’s effervescence and guitarist Andrew Blanch’s dry wit would have proved enough to win any audience over, even if their ensemble had sounded dodgy.

But it sounded convincing. The sonics were gentle yet sharply focussed with a real rhythmic drive that gave their program lightness and objectivity.

Then there’s the natural affinity of plucked strings of course. Furthermore, these two performers both have an enviable technical command that ensured there was fine precision and balance throughout.

For some the surprise might have been how powerful Granger’s Lyon and Healy harp could sound with only a guitar for company. But Blanch is a strong player and Granger constantly tempered her concert harp as both instruments intertwined and coalesced.

The players have had to be busy re-writing works for their ensemble and with the redoubtable Richard Charlton’s arrangements on hand as well, they gave enticing performances of Ravel’s evergreen Pavane pour une infante défunte and three of Granados’ Danzas Españolas.

There’s something about plucked strings that gave the Ravel a much stronger and very welcome dance feel than usually encountered.

Miniatures by Kats-Chernin and Ross Edwards were charming but Pujol’s Suite Magica and Pereira’s Fantasie Concertante were altogether bigger works actually written for guitar and harp and both performers made a strong musical impact with them.

– RODNEY SMITH

The 13 Storey Treehouse

Dunstan Playhouse

December 14 – 16

When Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton created The 13 Storey Treehouse back in 2011, it was an instant success.

The fantastic tales of best friends Andy and Terry — one wonders about the creators’ childhoods! — in their amazing treehouse (with bowling alley and see-through swimming pool) took the nation by storm.

The 2014 play by Richard Tulloch, making a return visit to Adelaide, is as fresh as a daisy. Back then, the book was still relatively new.

Now, a half-generation of kids have read each and every word not only of the original, but of all the rest in the series up to the 143 stories published earlier this year!

So putting it on stage, when your audience has every tall tale committed to heart, is no easy thing.

The premise, if one is necessary, is that Andy and Terry have arrived at the theatre to rehearse a play about their treehouse, but unfortunately they’re a week late, and they’ve forgotten all the props.

With the assistance of Stage Manager Val and her 2D-3D Converter, they do the best they can. The result is hilarious.

Use your imagination, the audience is encouraged, and with no set to speak of, just a steel frame, they use the simplest of props to create an imaginary world that seems perfectly reasonable even when it is off the rails. Why not try to hypnotise a giant banana?

A talented trio of Matthew Lee (Andy), Teale Howie (Terry) and Rebecca Rolle (Val) have a field day in this delightful holiday romp.

Nativity

Adelaide Town Hall

December 9 and 10

Richard Mills’ Nativity is a tour de force.

The composer’s new Christmas oratorio combined the forces of Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, Young Adelaide Voices, Adelaide Chamber Singers, Graduate Singers, and the SA Youth Handbell Ensemble.

Mills’ masterful orchestration brought out a spectacular range of colours and textures throughout the work. Part I contrasted cacophonous, dense passages dominated by pipe organs and brass with exquisitely delicate sections featuring the upper winds.

There was effective use of percussion in several movements. Mills’ use of bells and chimes – tubular bells, handbells, and tuned percussion -provided a sense of enchantment without falling into the usual Christmas music cliches.

– PETER BURDON

Nativity wove together settings of the Gospels with poetry from a range of sources spanning 7 centuries. Maureen Jipiyiliya Nampijinpa O’Keefe was especially affecting. Narrator Durkhanai Ayubi and soprano Desiree Frahn captured the melancholy of O’Keefe’s poetry over Mills’ atmospheric tone painting.

Several traditional Christmas carols were incorporated through the oratorio, including Silent Night, O Come O Come Emmanuel and The Coventry Carol. Mills’ setting of these well-known songs were inventive, particularly his use of cross-rhythms in Once in Royal David’s City, and the pensive quality of the older songs work well in amongst the Middle Eastern poetry in the second part of the oratorio. Stille Nacht, however, felt a little superfluous at the end, which could have finished with Mills’ beautiful setting of Lux fulgébit.

Despite the magnitude of the ensemble, this was a very tight premiere performance, with virtuosic playing and singing from all involved.

– MELANIE WALTERS

The Ajoona Guest House

Bakehouse Theatre

Until December 11

Over 20 or more years, Adelaide-born, award-winning playwright Stephen House has forged a career that now sees him widely performed in Australia and overseas. His monologues, in particular, have won wide acclaim.

House offers a unique journey into worlds and ways that are not often written a bout, and much of this is informed by his life as a “queer-nomad”, moving from place to place interstate and overseas, often unfamiliar, away from lovers and family and friends. This has sharpened the way in which he looks at others and observes their lives.

The Ajoona Guest House, the fruit of an Asialink India literature residency, adds to previous pieces that reflected on time spent in Paris and Dublin. Set in the grimy back-blocks of Delhi, the Ajoona is the home-away-from-home for a colourful array of misfits.

It’s often been said that House’s characters are always looking for something better in their lives. Their glass is always half-full. So it is with the Ajoona, even though the travelling companions are all-too-often poverty, addiction and misery. If aspirations haven’t failed, they’ve been sorely tested. The recurring mantra ‘Om Shri Ganeshaya Namah’ seems to often fall on deaf ears.

House weaves in and out of his character’s lives with consummate skill. And the writing is really fine. Lines like the “steady stream of a messy memory” and “dangerously brittle wandering emotions” reflect his growing stature as a poet.

House has always been generous in sharing his work with others, and engaging Rosalba Clemente as director ensures that dramatically, and dramaturgically, the hour-long piece utterly engages.

It might be a dump, but The Ajoona Guest House gets five stars.

– PETER BURDON

Symphony of Angels, Festival Of Orchestra

The Angels and Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Showgrounds

December 3

Surrounded by classical music while growing up, it seemed inevitable that one day the Brewster brothers John and Rick would join an orchestra.

But when their late grandfather Hooper founded the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra in the 1930s, I’m sure not even he could imagine the triumph of bringing South Australia’s most prestigious classical ensemble together with our most celebrated pub rock band.

After playing several seasons around Australia, Symphony Of Angels made a thrilling return to the band’s home city at the ASO’s final weekend of the Festival Of Orchestra drawing a mixed crowd of die-hard Angels fans of young and old alongside a healthy serving of Adelaide’s chardonnay set.

All united under the spell of Rick and John Brewster on guitars, Nick Norton, drums, and Sam Brewster on bass alongside lead vocalist Dave Gleeson who, it has to be said, really is the ultimate showman.

The 20-song set rocked off to a great start with “After The Rain” and ripped through classics like “No Secrets” and “Face The Day”.

Concertmaster Rob John’s arrangements shine in this production.

So many times when a classical orchestra attempts rock or pop, it can fall into the trap of just plonking the strings on top of an existing piece of music like some sort of orchestral karaoke. In Symphony of Angels the orchestra and the band are married beautifully. Moments of counterpoint between Rick Brewster’s guitar solos and the orchestra are a perfect demonstration of this.

There were also beautiful instances of tenderness found in a tribute to original front man Doc Neeson, a touching version of the ballad “Love Takes Care”, as well as the follow up “Be With You”.

Of course it’s those rip-roaring rock hits that really got the crowd going with “Mr Damage” turning the ASO up to turbo and could there ever be a better encore in music than the iconic “Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again?” I think the audience answered that best. “No way. Get F … ed. F … Off!”

MATT GLBERTSON

UKARIA 24 – Virtual Travels

UKARIA

November 28

Genevieve Lacey did a lot of tweeting onstage at this concert.

Not with her smartphone, in case you were wondering, but with various small recorders with which she trilled and chirped. It started with a concerto by Sammartini with enough coloratura to impress a nightingale. Later, in a New Age-ish arrangement by Erkki Veltheim of one of Hildegard of Bingen’s melodies, she tweeted like a bird on the smallest recorder you are ever likely to see.

Accompanying her throughout were Kristian Winther and Andrew Haveron (violins), Tobias Breider (viola) and Umberto Clerici (cello). These four players got together for Peter Sculthorpe’s String Quartet No. 8, a work that includes a number of the composer’s favourite sound effects (but no seagulls) scattered amongst melodies of a predominantly sombre character. That description probably doesn’t do it justice – it’s a taut and rather compelling piece, played here with suitable intensity. The biggest surprise came at the end with a string quintet version – possibly by the composer – of Beethoven’s famous, or infamous, Kreutzer Sonata, originally for violin and piano, in which the string players were joined by an additional cellist in the form of ASO principal Simon Cobcroft. This arrangement is a fresh take on a familiar work, extremely difficult, and brilliantly played, sometimes at precipitous speed.

Stephen Whittington

A Night on Broadway

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra Festival Of Orchestra

Adelaide Showgrounds, 1 December

The Adelaide Symphony Orchestra’s Festival of Orchestra has already proved a wild success, with orchestral favourites, a choral spectacular and an unforgettable night with Ministry of Sound. Now it’s on to Broadway.

Amy Lehpamer and Simon Gleeson joined the ASO under the baton of the effervescent Guy Noble for a tour that took in well-trodden paths and some of the by-ways of musical theatre.

The program predictably showcased the soloists’ skills and popular performances. Lehpamer’s pieces from The Sound of Music and Gleeson’s Bring Him Home from Les Misérables were worth the price of a ticket.

But there were also songs they’d always wanted to sing, and anyone considering a revival of Chicago any time soon could do worse than to cast Lehpamer, whose All That Jazz took the place by storm. She gave Maybe This Time from Cabaret a red hot go as well.

The ASO was in predictably fine form. They adore Noble — in spite of his legendarily dreadful puns — and rose to the occasion in some really difficult pieces, like the overtures to Gypsy and Candide, and the brilliant Carousel Waltz.

Just a few days after the death of Stephen Sondheim, it was a bittersweet occasion for music theatre fans, so the last-minute inclusion of the lovely duet Not While I’m Around from Sweeney Todd, with Noble at the piano, was a precious moment.

The entire audience was up for Do-Re-Mi by way of encore. When you’ve got an oval full of people singing, you must be right.

– PETER BURDON

Carmina Burana

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Showgrounds

Blessed by Venus, high in the western sky, the ASO continued its orchestra festival. You could not have guessed the outstanding Luke Dollman was a late substitute for Benjamin Northey.

He was so at home with the music. The orchestra responded to him joyfully but the evening belonged to the four Adelaide choirs open hearted open throated totally committed singing.

It was, as they say in the sports pages, very much a game of two halves.

Peter Sculthorpe’s Earth Cry is the European Australian response to the landscape, a work of imposing sonorities, with references of indigenous Australia. That identity was front and centre in Bulu Yabra Banam written by Jason Rotumah and Leigh Harrald featuring Robert Taylor on yidaki.

Created as a part of the Floods of fire community composition project it was a striking work, though the pentatonic theme made it sound like a Chinese marching band at times, it certainly deserves more hearings.

Julian Ferraretto and the students of Carlton School Port Augusta made The 2016 Floods, its light textures enriched by the voices of the Adelaide Connection, the Elder Conservatorium Jazz choir. Both these works will heard again next year.

‘O Fortuna’, the most popular choral and orchestral couple of minutes of the last century or so. Carl Orff’s calling card. Totally recognizable, but only the introduction to a splendid oratorio, based on medieval texts from the monastery at Benediktbeuern in Bavaria.

To hear it or to sing it is a joyful experience, full of energy, vocal and instrumental colour.

The three soloists were splendid. Samuel Dundas was commanding as frustrated lover and drunken abbott.

Andrew Goodwin was luxury casting in his brief solo as the roasted swan but Jessica Dean crowned the night. Her Dulcissime was a sensual surrender to the joys of love.

The sound mix could have brought the excellent choir of almost two hundred voices to more prominence but the audience was delighted. The evening was chilly but that music warmed your bones.

The affable compere, Guy Noble, made much of the raunchy nature of the work. Check out Catulli Carmina, Orff’s sequel. It’s pure 1st century Roman filth. Translated surtitles could get you arrested. It’s a great sing.

– EWART SHAW

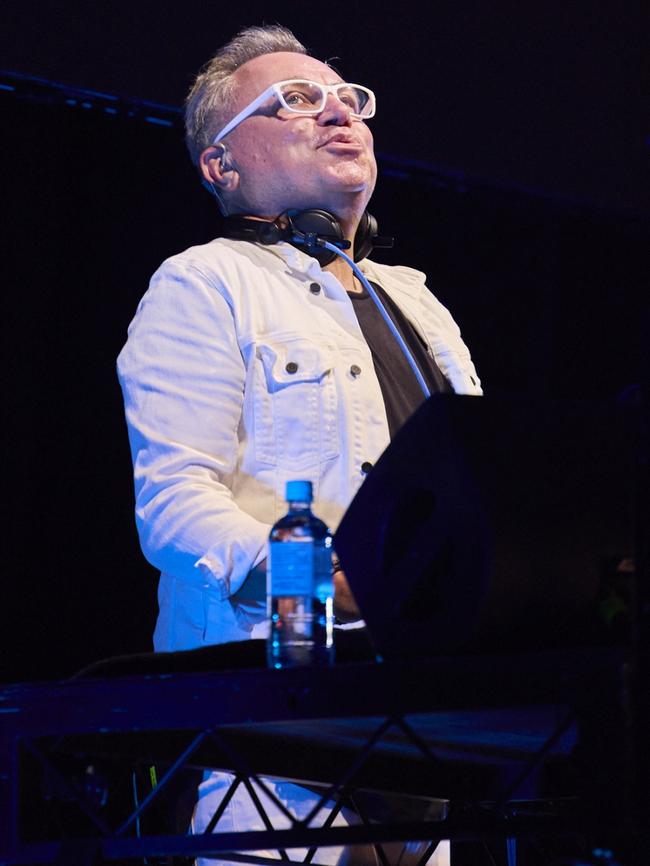

Ministry of Sound: Classical

Featuring Groove Terminator, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, Gospo Collective

Festival of Orchestra, Adelaide Showground

November 26

Veteran Adelaide house DJ and producer Simon “Groove Terminator” Lewicki was up against it on Friday night.

Not only was dancing restricted to an area directly in front of your chair but an unusually bitter November southerly buster was doing its best to kill the mood. Ibiza this was not.

But GT overcame these odds and delivered a finely crafted mix of high and low art as part of the six-night Festival of Orchestra – or FOFO if you’re so inclined – with a bang.

Of course, house music has long sampled the strings and horns of classical music, so the combination of DJ and symphony orchestra is not the stretch it might seem at first.

What Else Is There by Royksopp allows Gospo Collective’s vocals to shine, and a remixed version of Eurythmics’ Sweet Dreams gets a rousing cheer.

The first half closes with a couple of bangers – Fisher’s Losing It merging seamlessly into Darude’s classic Sandstorm – before part two lifts things up a notch.

Nineties chill-trance hit Children works perfectly with the orchestra, and Underworld’s Born Slippy and Fatboy Slim’s Right Here, Right Now have everyone out of their seats and dancing … in a responsible manner.

It all wraps with a Mr Brightside singalong and, for a brief moment, the world feels a little normal again. It’s much needed.

– NATHAN DAVIES

G – Australian Dance Theatre

Her Majesty’s Theatre

November 25-29

A revival of Garry Stewart’s G is a fitting capstone to his extraordinary 22 years at the helm of Australian Dance Theatre.

Having followed his deconstruction of Giselle from its first moments in development through seasons in Adelaide and interstate – and the company has taken it overseas as well – the feeling, seeing it again, is that it is a nationally and internationally significant piece, deserving of a permanent and prominent place in the history of Australian dance.

All the hallmarks of Stewart’s work are there: intense physicality, coupled with respect for classical forms.

The opening sequence gives it all away. The noble overture with its poised, elegant movement gives way to Luke Smiles’ brooding, then pulsing, then driving score, and in short order the dancers fly across the stage, hurling themselves fearlessly into leaps and rolls.

Allusions to the original, like the crossed hands of the ghostly wilis, royal crowns, and the sword by which G dies, pepper the piece. But there it ends, for this is not about love and betrayal, but of far more elemental, primitive forces.

This performance reinforces G’s place in Stewart’s generational journey, with the brute force of his 2006 Devolution reflected in some of the angrier movement, and (by dint of Stewart’s research into female hysteria in Victorian psychology) prefiguring the cerebral Be Your Self in 2010.

G is not only Stewart’s farewell, it also marks the retirement of long-serving ADT dancer Kimball Wong, whose debut with the company was in G back in 2008. Wong fittingly dances one of the few solos in the work, and marvellous it was.

Reviewed glowingly in 2009, I wrote that G was “most thrilling Australian dance work you could hope to see”. Nothing has changed.

Thank you, Garry Stewart, for everything.

– PETER BURDON

Classical Spectacular

Festival of Orchestra, Adelaide Showground

November 24

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra made a brilliant start with the first of its festival of outdoor concerts.

Entitled Classical Spectacular, that’s exactly what thousands of fans in Adelaide Showground’s arena experienced in no uncertain terms. Fireworks, army artillery and a program of classical hits from Tchaikovsky to Bernstein disarmed any critics with the event’s sheer joie de vivre.

Everything went right on this oh-so-important evening for our ASO as it made its mark again on our collective consciousness after SA has just opened up. At the last moment the weather changed from dire to near perfect, sound systems and pyrotechnics were on cue and above all the ASO, with conductor and irrepressible compere Guy Noble, performed a bevy of popular classics very well indeed.

After dark and with only the illuminated stage and screens to occupy our attention, the experience became quite cinematic with one all-important exception. This was in real time, and there was a feeling of spontaneity generated by the enormous audience and a live orchestra onstage. There is nothing like live music making.

Although the classical music was undoubtedly larger than life there were subtleties too. Ravel’s Boléro contained beautifully contoured solos from ASO principals and Constantine Shamray’s virtuoso pianism shimmered and simmered in Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Nevertheless, spine tingling theatrical outbursts were the order of the day with Graeme Koehne’s pulsating Elevator Music and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture in the lead. Wayville Showground was perfect for such a musical roller coaster.

– RODNEY SMITH

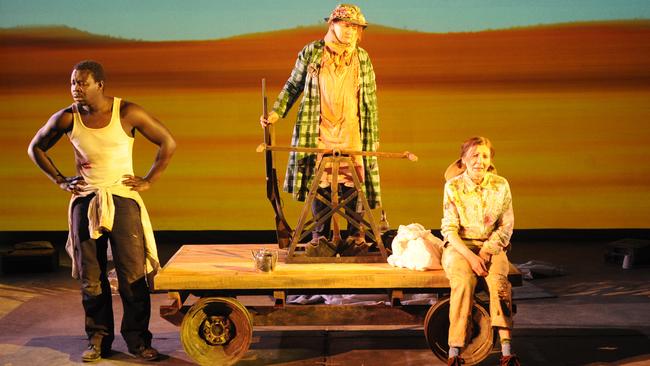

Dry

Hart’s Mill

November 17-20

Local independent producer Far & Away Productions has teamed with Country Arts SA to present Dry, a new piece by popular local creative Catherine Fitzgerald.

A few weeks in the regions ends with a short run at the atmospheric Hart’s Mill in Port Adelaide.

The location was very apt, a mid 19th century shell, abandoned and derelict for 30 years or more.

Dry concerns two sisters, Patience (Eileen Darley) and Ellen (Caroline Mignone), who’ve steadfastly held out against the attempts of Government – described only as “the Capital” – to displace the population of a tiny outback town on the shores of an inland sea.

When a stranger, an escapee from a remote internment camp (Stephen Tongun) crashes into their lives, a desperate duo become a troubled threesome.

The sisters are at perpetual odds. Both are intensely invested in their family home, though not for the same reasons. Ellen might leave if only her absent husband would return, but Patience (a gun-toting, foul-mouthed, and the very antithesis of her name) would rather starve. The unnamed stranger reinforces the message about the evils of Government which seeks to control through manipulation and fear.

Dry is beautifully written, showing the benefits of Fitzgerald’s long career in the theatre. There are hints of Orwell, and also of Beckett, but it’s unmistakably an Australian story. Fitzgerald directs her own work with predictable skill, while the influence of playwright Patricia Cornelius – an uncompromising voice, if ever there was – makes for something really special.

The epic Australian outback – photography by Alex Frayne projected with stunning clarity by lighting and AV designer Nic Mollison – is breathtaking, while the hole is underpinned by a subtle score from Catherine Oates.

Dry is a candid warning about the peril society faces if it continues to maltreat the environment. And that Government complicity is a worse thing still.

– PETER BURDON

Seraphim Trio

Adelaide Town Hall

November 18

Beethoven in titanic mood is not to be trifled with. But he can be approached in many different ways and Seraphim Trio’s intimate portrait of the composer as a man for all seasons in their warmly personal performance of the Archduke Piano Trio in Bb major Op. 97 drew in listeners through pianissimos rather than fortissimos.

The noble main tune of its first movement Allegro moderato, almost Schubertian in its expanse and lyricism, was as supple and persuasive as you could wish for and the more rhythmical second theme danced deliciously. Indeed, the general mood appeared almost genially reminiscent at times. This was definitely not big hair Beethoven.

The Scherzo was light, agile and beautifully polished with none of the rumbustious qualities one sometimes hears. And the Trio’s reading of the work’s centre of gravity, an enormous Andante cantabile, eschewed intensity and declamation in favour of welcoming warmth and inner musings of a man you might really want to know.

Even the normally unbridled high spirits and humour of the final Allegro moderato were tempered with better manners than sometimes encountered.

In all this guest cellist Simon Cobcroft blended seamlessly with Seraphim’s regular players violinist Helen Ayres and pianist Anna Goldsworthy as if he had been part of this long-established group since day one.

Haydn’s cheeky Trio No 43 in C major opened the program very much as a teammate rather than a mere warm-up. And so it deserved to be.

– RODNEY SMITH

Wyrd Sisters

Unseen Theatre – The Bakehouse

Season to November 27

Unless you know and love Terry Pratchett, nothing of what follows will make sense, but then Unseen Theatre, now 21 years old, has been delighting his fans with an unmistakeable house style, thanks to founder Pamela Munt.

Stripped of Pratchett’s lapidary prose, the play is a paean to the power of words and theatre to create change and real enchantment.

For this Discworld version of Macbeth, the three witches are the goodies, saving the infant heir to Lancre after the murder of his father by his uncle and aunt.

They then use wibbley wobbly timey wimey stuff to make all well.

Munt takes on her signature role as Granny Weatherwax, handing direction over to alumni David Dyte and Hugh O’Connor. Her sister witches are Granny Ogg, Natalie Haigh, and Magrat Garlick. Alycia Rabig.

The truly venerable Philip Lineton kicks off the story with Shakespearean fire and it’s on for fun and all.

There’s fine work from Tony Cockington as usurping Duke Felmet and Aimee Ford as his murderous duchess, with Paul Messenger as the ghost of King Verence.

Danny Sag, in an amazing costume, plays the Fool, and Chris Irving is Tomjon, thespian and true king.

Around them flow seven players of multiple parts, it’s best not to try and keep track.

As Duke Theseus says in a greater play about magic and love, the best of this kind are but shadows and the worst are no worse if imagination mend them.

With the Bakehouse slated for demolition, Unseen will be looking for a new home.

Granny Weatherwax ends the play ‘Let’s just leave the whole question open, shall we?’

– EWART SHAW

Teddy Tahu Rhodes and Guy Noble – State Opera of South Australia

Her Majesty’s Theatre

November 19

Teddy Tahu Rhodes is where we like to find him, front and centre on the operatic stage.

True, he not actually in this Barber but he sings both Rossini and Mozart’s Figaro in this rewarding recital of some of his favourite things.

The familiar voice is strong and compelling, a little too strong for the German lieder and Handel’s Ombra Mai Fu, originally written for the castrato Caffarelli.

On familiar ground he’s unbeatable. His O What a Beautiful Morning, It Might as Well be Spring and especially his Some Enchanted Evening were crowd pleasers.

Guy Noble, best known as a conductor, is a willing accomplice, with a wicked sense of humour. His G and S parody skewered Barnaby Joyce and took a hard jab at anti-vaxxers. The audience roared with laughter.

In the second half Rhodes included the dramatic Ella Giammai M’amo from Verdi’s grand opera Don Carlos. It’s on his wishlist to be in that opera, but I don’t think Stuart Maunder and State Opera have it on their schedule any time soon.

The Australiana bracket included songs by Jack O’Hagan including On the Road to Gundagai made famous by that earlier popular baritone Peter Dawson.

Indeed there was a beautiful sense that these two mates had just stopped by to put on a concert for the locals in a pub or church hall.

Rhodes finished the evening with a gentle Maori song, because while we claim him as Australian, he’s actually trans-Tasman in origin.

These two are always welcome and if they are ever short of songs to sing, may I recommend Flanders and Swann or Flotsam and Jetsam?

– EWART SHAW

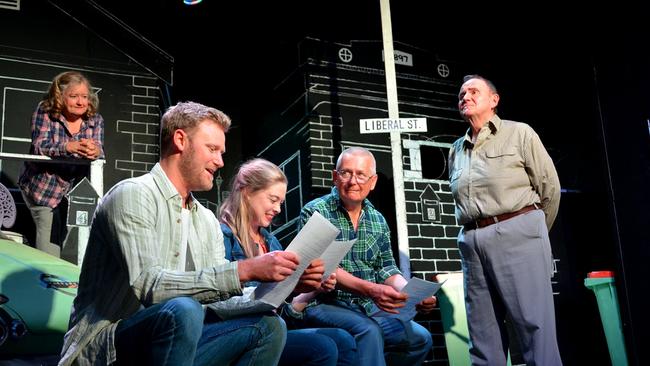

Eureka Day

State Theatre South Australia – Dunstan Playhouse

Season to November 27

Back in late 2019, State Theatre Artistic Director Mitchell Butel came across a play by a little-known US playwright that had received rave reviews during an off-Broadway run in a 70 seat house.

Something about a very progressive school, Eureka Day, whose egalitarian ethos is mightily

challenged by the issue of – wait for it – mandatory vaccination.

The disease in this case is mumps, an outbreak of which has given rise to a State-mandated

vaccination drive.

But the school’s consensus-obsessed Executive Committee suddenly finds itself riven by disagreement so profound as to surely be irreconcilable. But seek approchement they do, and in this quest are laughter and tears in equal measure.

The committee is the cast, and they are uniformly outstanding. Glynn Nicholas is exquisite as the hippyish principal Don, reading from Sufi poetry, while Caroline Craig is on fire as the overweening, tragicomic Suzanne, whose drive for inclusivity knows no bounds – at first.

Eli (Matt Hyde) is a wealthy stay-at-home dad, unfazed by the conventions of matrimony and having a fling with the shy Meiko (Juanita Navas-Nguyen).

Into this transcendental love-in bounds newcomer Carina (Sara Zwangobani), who is black, gay, and has a child with special needs. You’d think that would be par for the course at Eureka Day. Think again.

When the Executive cannot agree on a vaccination requirement, a “Community Activated

Conversation” is convened.

The Executive meets online to present the matter to the wider school community, who contribute with comments on a live-feed, projected on screen.

This feed is an unsubtle – and wildly funny, you’ll laugh your head off – act of genius, brutally exposing anti-vax claims and conspiracy theories for the arrant nonsense they are, while not allowing the do-gooding pro-vax team to dodge the bullet of being inexorably middle class, and not above selling their own souls for safety and security.

Rosalba Clemente directs with consummate skill. The set by Meg Wilson is a delight, a clever skeletal construction, but with many fine details, like the alphabet on the walls – “a is for activist” – and posters of notable historical figures on the wall. Joan Baez and Frida Kahlo, for example.

Given COVID-19 was hardly a ripple in the international pond when Mitchell Butel programmed Jonathan Spector’s play, one can but marvel at his prophetic powers.

Eureka Day is a must-see.

– PETER BURDON

How Not to Make it in America

Theatre Republic – Space Theatre

Season to November 20

Local independent Theatre Republic has done some mighty impressive work in its first four years, and its premiere production of Emily Steel’s new play How Not To Make It In America, directed by Corey McMahon, is no exception.

Matt is an aspiring actor who’s followed his friend Michelle to New York, there to try his hand in the big league.

Needless to say, it’s a brutal reality check, and when he chooses to overstay his visa, he finds himself couch surfing and increasingly desperate.

The consistently excellent James Smith gives yet another superb performance in a role that could easily be mundane, given it treads very well-worn paths.