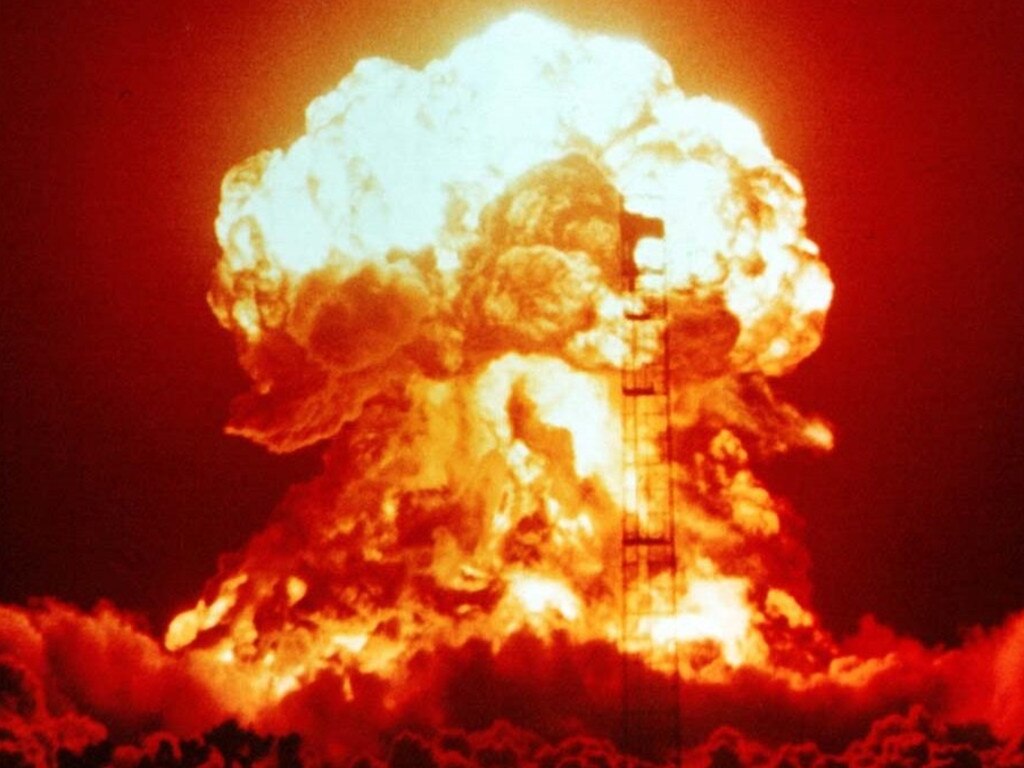

2024 threatens to take the world one step closer to hell

Two large-scale wars raged in 2023 but the threat in coming this year could be like nothing Australia has ever seen.

2023 was a terrible year on the world stage. But, after spy balloons and sonar assaults, terror attacks and forced migrations, 2024 threatens to take the world one step closer to hell.

“Can we stop things falling apart?” ask International Crisis Group think-tank executives in its yearly threat assessment.

“2024 begins with wars burning in Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine and peacemaking in crisis. Worldwide, diplomatic efforts to end fighting are failing. More leaders are pursuing their ends militarily. More believe they can get away with it.”

The threat list is exhaustive.

We know about Israel’s war on Gaza. And how this could easily extend to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, Yemen – and Iran.

Then there’s Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And the flow-on effect of this upon Georgia, Romania, Belarus and Poland.

And China has made no effort to hide its designs on India and the South and East China Seas over the past decade.

But the list of global hotspots goes much further.

Once considered secure, Sudan has fallen into civil war. Other African states seemed doomed to follow suit.

Russia has again arbitrarily extended its territorial claims over the rapidly thawing Arctic Ocean. And it is threatening to use its ice-optimised military to enforce this.

Serbia has revived its ambitions over Kosovo, threatening renewed conflict in Europe’s Balkans.

South America’s Venezuela has taken a page out of the playbook of China, Russia and Israel. It insists it has “historical rights” to almost two-thirds of neighbouring Guyana.

Myanmar’s long-running civil war is heating up even as it accelerates its campaign to evict its Rohingya ethnic minority. But fighting has flared on its border with China – potentially offering expansionist Beijing an excuse to step in.

While tensions between India and Pakistan have stabilised in recent years, Afghanistan’s religious-extremist Taliban movement has begun actively destabilising Islamabad’s control.

And subsea sabotage of internet cables and gas pipelines has escalated dramatically over the past year. While circumstantial evidence points towards the involvement of Russia and China, the remoteness of such incidents offers offenders the shield of “plausible deniability”.

“So, what is going wrong?” ask Crisis Group’s CEO Comfort Ero and Vice President Richard Atwood. “The problem is not primarily about the practice of mediation or the diplomats involved. Rather, it lies in global politics. In a moment of flux, constraints on the use of force – even for conquest and ethnic cleansing – are crumbling.”

A world of pain

“Looking ahead to 2024, there are plenty of things in the world to keep national security wonks up at night,” Foreign Policy analysts warn in their “peering into the crystal ball” report.

And there are simply too many international flashpoints to examine here.

But Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review emphasised the nation’s exposure to conflict within the Indo-Pacific region, which extends from the embattled “Gate of Tears” in the Middle East’s Gulf of Aden to the polarised political turmoil of Washington DC.

Here, “the flow of events and developments is relentless”, summarises The Council for Security Cooperation In the Asia Pacific (CSCAP).

Its new Regional Security Outlook 2024 report warns “it is clear that our region is confronted with a truly formidable policy challenge, a challenge that will demand the best of all of us”.

And this, it adds, is threatening the so-called rules-based order established after World War II to “deter and defuse the propensity for the anarchical character of the international system to descend into open war between major powers.”

China

“In the case of China, concerns extend to its international law-defying territorial ambition,” former Labor Foreign Minister Garth Evans highlights in his contribution to the CSCAP outlook.

This, he says, includes its “militarisation of the South China Sea, with its ‘9-dash line’ this year expanded to 10; its repeatedly stated determination to unify Taiwan with the mainland, not excluding the use of force, in a context where its repressive actions in Hong Kong have made reunification on a ‘one country, two systems’ basis a nonstarter.”

Evans highlights Beijing’s “continued assertiveness on other territorial fronts”, including Japan and India, and “its efforts to increase its presence and influence in smaller but strategically significant regional players, including the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea and Timor Leste”.

“Above all, there is anxiety – compounded by Beijing’s manifest determination to challenge the nature and extent of the US security presence in the region – about the very significant expansion and modernisation of its military, including nuclear, capability,” he adds.

The International Crisis Group points to recent meetings between Beijing and Washington = including Chairman Xi Jinping and President Joe Biden – as a sign both sides are aware of the immense cost of open conflict.

“But their core interests still collide in the Asia Pacific region – and Taiwanese elections and South China Sea tensions could test the thaw,” the think-tank concludes. “For now, probably the biggest danger is that Chinese and US planes or ships collide.”

China-Taiwan

Tensions surrounding Taiwan were more relaxed in 2023 than when US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited in 2022.

But Beijing’s temper has flared as Taiwan’s January 2024 presidential election race speeds up. Once again, Chairman Xi has threatened invasion if Taiwan even dares to broach the subject of formal independence.

Taiwan has never been part of Communist China. The island democracy of 23/5 million evolved out of the last bastion of resistance against Chairman Mao Zedong’s revolution by the authoritarian Republic of China.

“China’s long-term ambition to regain Taiwan is clear, but the downside risks of taking precipitate and unprovoked strike action – for both its internal prosperity and stability and its wider international reputation – would seem to outweigh any possible rewards,” states Evans. “That said, the prospect of an invasion – however remote – will continue to divide Australian opinion.”

Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (ASPI) director Gregory Poling agrees.

“Reams of ink have been spilled over the rising tension across the Taiwan Strait and hypothetical timelines for a future Chinese invasion. But US-China conflict over Taiwan does not seem imminent, and any escalation would almost certainly be intentional,” he writes in his CSCAP outlook.

Instead, Poling fears “an increasing trend of dangerous interactions” between Chinese and other national militaries “over international waters in the East and South China Seas” could trigger a crisis. “PLA aircraft are intentionally creating risks of midair collision about every 2.5 days. At that rate, an eventual accident is a mathematical certainty.”

China-Philippines

Beijing’s insistence that it owns the entirety of the South China Sea has been a source of steadily intensifying dispute for decades. But it began arbitrarily asserting control after a 2016 UN Permanent Court of Arbitration judgement rejected its claim as unfounded.

“Chinese ships are using more aggressive tactics, including water cannons and acoustic devices,” the Crisis Group states. “They shadow Philippine vessels in ways that court incident, prompting boats from the two countries to collide in October and December.”

“Given this game of chicken, it was surprising that it took until October to have the first collisions,” ASPI’s Poling adds. “And if it keeps up, there will eventually be an even more violent and potentially deadly incident.”

After spending a decade building up its own network of artificial island fortresses in the area, Beijing last month warned Manila it would ‘respond resolutely’ if it attempted to construct a structure on Second Thomas Shoal.

But Manila, for its part, has secured support from Australia, Japan, South Korea and the United States in patrolling and policing its UN-recognised maritime borders.

“In the end, while SCS maritime issues are a primary concern, the Philippines is also beset with other challenges within the security-development nexus: internal peace and order, terrorism, criminality, natural disasters, food, and energy insecurity, among others,” University of the Philippines-Diliman professor of political science Aries Arugay writes for CSCAP.

China-Japan

Beijing has cemented its territorial claims to the South China Sea through heavily armed artificial island fortresses. But it’s moving to secure its claim over Japan’s Senkaku Islands by establishing a permanent presence of coast guard and naval vessels in their vicinity.

It was this assertiveness that resulted in three divers from Australia’s HMAS Toowoomba being assaulted with sonar by a Chinese warship while attempting to free their frigate’s propellers from a tangled net. This happened in UN-defined international waters – regardless of whether it was in an economic zone belonging to China or Japan.

Along with Chinese naval posturing off the Okinawa Islands, such incidents have prompted Japan to increase its spending on defence dramatically.

Beijing is outraged, insisting Tokyo’s new defence posture “grossly interferes in China’s internal affairs and provokes regional tensions.”

But Doshisha University Professor Kanehara Nobukatsu argues that it is Japan feeling threatened.

“Potential adversaries like China, North Korea, and Russia have large numbers of ballistic and cruise missiles that can reach Japan,” he writes for CSCAP. “China is currently capable of landing 2000 missiles on Japan. South Korea and Taiwan also have missiles of the same kind.”

Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has committed to acquiring 400 US-made Tomahawk cruise missiles. But this is just the first step towards securing broader counterstroke capabilities.

“It means that Japan will be able to say ‘We will shoot back,’ when missiles are about to be fired toward Japanese soil from North Korea, China, or Russia,” argues Kanehara.

China-India

Hopes that New Delhi would strengthen its strategic alignment with the West grew after it lost control over some 1000 square kilometres of its Ladakh Himalayan border with China in 2020.

However, recent moves by Prime Minister Narendra Modi have revived doubts over its ability to become a reliable partner in a revived Quad partnership with the US, Japan, and Australia.

New Delhi has abstained from votes condemning Russia over the invasion of Ukraine. And it has moved to strengthen economic ties with Moscow as other nations seek to impose punitive sanctions.

“Reluctant acquiescence … was obtained from Washington on the implicit premise that New Delhi’s anti-China posture in the Indo-Pacific region would be preserved,” says Institute for China-America Studies senior fellow Sourabh Gupta.

But the Modi government is showing authoritarian tendencies of its own.

It’s been accused of planting spyware on journalists’ phones. It’s been silencing political opponents. Its agents have been linked to the assassination of a Sikh activist in Canada and a failed plot for a similar attempt within the United States.

“And … the Modi government trashed a Permanent Court of Arbitration order on a preliminary award pertaining to the Pakistan v. India Indus Water Treaty proceedings in language eerily similar to that reserved for the Philippines v. China South China Sea tribunal by Beijing,” Gupta adds in his CSCAP assessment.

North Korea

The “fire and fury” rhetoric of past years may have simmered down. But Pyongyang, in 2023, test-fired more than 70 homegrown missiles and successfully placed one of its own satellites in orbit.

Both capabilities are something Australia has yet to achieve.

Now Foreign Policy’s 2024 “crystal ball” foresees Chairman Kim Jung-un turning up the diplomatic heat once again.

“North Korea conducted six explosive nuclear tests between 2006 and 2017, and we predict that 2024 is the year that it notches a seventh,” the analysts write. This will “constitute another major diplomatic crisis on the Korean Peninsula and a reminder that decades of US pressure to get Pyongyang to abandon its quest for the bomb have all failed.”

Dr Jaewoo Jun of the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses points to Chairman Kim’s rhetoric – including the political theatrics of locking the use of nuclear weapons into North Korea’s constitution – as forcing South Korea to consider similar moves.

In 2023, Seol inked a “Nuclear Consultative Group” with Washington to incorporate the threat of nuclear weapons into its own defence strategy. “In fact, of course, the Washington Declaration was intended to help defuse the significant domestic support that had arisen for an indigenous South Korean nuclear weapons program,” Jun writes for CSCAP.

Amid it all, North Korea’s ties with Russia have been strengthening. And precisely what President Kim has secured from President Putin in exchange for hundreds of thousands of artillery rounds for use against Ukraine is yet to be seen.

The United States

“The alarming vagaries of its domestic politics have created concerns across the board about its will and capacity to stay the course in its long self-appointed role as regional security stabiliser and balancer,” states Evans.

This isn’t just a matter of regional military presence, he adds. It’s “also about its retreat from the open trading policies that have contributed so much to the region’s economic prosperity,

and consequent stability”.

The International Crisis Group, however, argues “US power is not in free fall. The problem is more the United States’ political dysfunction and seesawing, which brings volatility to its global role.”

This year’s presidential election is the source of great global anxiety, the think-tank adds. “A potentially divisive 2024 vote and the possible return of former US President Donald Trump – whose fondness for strongmen and disdain for traditional allies already rattle much of Europe and Asia – make for an especially uneasy year ahead.”

But Foreign Policy’s analysts buck this trend. Despite Biden being more unpopular than any of the past four single-term US Presidents, “we predict that after a gruelling and exhausting Biden-Trump rematch, Biden will narrowly eke out a win for a second term, in yet another election cycle marred by disinformation that will muddy the waters on what’s fact and what’s not”.

Harsh reality, or self-fulfilling prophecy?

Much of the world reacted with surprise at President Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. But he’d been proclaiming his intention to do so for years.

Are China’s Chairman Xi Jinping or North Korea’s Kim Jong-un counting on the same hopeful optimism?

The observable reality is in the efforts of Russia, China, and North Korea to expand their military reach and influence. And the nervous response of neighbouring nations attempting to counteract these.

The rest is about words. And how much faith one puts in them.

“China’s revisionist interpretations of international law – including both its efforts to claim historic rights across the South China Sea and to restrict foreign military activity in the international waters and airspace of the Taiwan Strait, East China Sea, and South China Sea – is not going to change any time soon,” argues Poling. “And Southeast Asian claimants seem equally unlikely to abandon their lawful rights in the face of Chinese coercion.

“The disputes are, therefore, something to be managed rather than solved for the foreseeable future.”

Should Southeast Asia – including Australia – be alert? Or alarmed?

“The unhappy reality – and this perception is, again, shared across most of the Australian policy community, as around the region – is that nations can sleepwalk into war, even when rational, objective self-interest on all sides cries out against it,” warns Evans.

And “loose talk of war in Beijing, Moscow and Washington risks normalising the almost incalculable cost of a clash,” warns the International Crisis Group.

“It seems unlikely that world leaders, given their divisions, will recognise how perilous things have become … Probably the best we can hope for this year is muddling through.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

Originally published as 2024 threatens to take the world one step closer to hell