‘Incoherent’: Fatal contradictions dragging down Donald Trump’s tariff strategy

Donald Trump keeps flip-flopping on his tariffs. But that is not the only problem that threatens to derail them permanently.

We have observed the unfolding of Donald Trump’s tariff strategy over almost three months now. Long enough, I think, to diagnose the glaring problems at its heart.

Let’s run through the first of these problems very quickly, which will give us all the more time to discuss the second.

The US President is implementing his tariffs in a manner that is chaotic, and unpredictable, and that in itself could be enough to cripple elements of his own country’s economy.

Multiple times now, he has imposed severe tariffs on other nations only to pause or rescind them within days, or even hours. He did it with Canada and Mexico back in February. He did it with the worldwide “reciprocal” tariffs this month. And now he’s gone and done it with a hefty chunk of the tariffs on China.

The uncertainty this sows is deeply damaging, particularly to business confidence and to investment, both of which underpin so much economic activity.

Businesses need to know the rules of the game will be stable. How are they meant to make any long-term decisions when their costs might abruptly spike, without notice, on the whim of one erratic man? How do they choose whether or not to hire new staff, when those new employees’ wages might suddenly stretch their budgets beyond breaking point?

The risk involved here creates a kind of stasis, where everyone is stuck, unable to make big moves until economic certainty returns.

And it affects the markets as well. Before Mr Trump announced a 90-day pause on the bulk of those worldwide tariffs last week, we saw a rare, ominous phenomenon: the stock market was diving, and simultaneously, investors were selling US Treasuries.

Usually a jitter in the stock market sends people rushing towards US Treasuries – buying American debt, essentially – because it is seen as the safest investment.

What we saw last week, then, was a new and troubling lack of confidence in the American government, which would be hard to reverse even if Mr Trump were, somehow, to now start behaving more stably.

So there’s that. Problem number two is a series of fundamental contradictions within the Trump administration’s tariff policies. The tariffs aren’t just potentially damaging, to America and to the rest of us, in a practical sense. They are also internally incoherent.

Contradiction one: What are the tariffs meant to achieve?

The first thing you do, or at least should do, when crafting a policy is to clearly identify the problem you are trying to solve. What is the end goal?

We have heard multiple, contradictory answers to that question from Trump administration officials, and indeed from the President himself.

Are you imposing tariffs to force a revival of American manufacturing? Is the goal here to stop bringing in cheap clothes from Bangladesh, or stop accepting cars from Europe, and to make all that stuff in the US instead?

Or are the tariffs supposed to generate a ton of new revenue for the American government, which can then be used to fund income tax cuts or, in the wilder dreams of Mr Trump and some of the other wealthy men in his orbit, eliminate income tax entirely?

Which is it? Because it cannot be both. The two goals are diametrically opposed; they actively work against each other.

If you end up raising a heap of revenue from the tariffs, someone must be paying them. Which means the imports from all those other countries haven’t stopped. So no resurgence of US manufacturing.

If the imports do stop, and the products end up being made in the US, then nobody is paying the tariffs. Which means no revenue.

No one in the Trump administration seems to have properly wrestled with this contradiction, judging by their public comments. Certainly not Mr Trump himself, who constantly promises the tariffs will deliver both outcomes at once.

Put aside the fact that goal number one would be better pursued by targeted, industry-specific tariffs, rather than the administration’s decision to, for the most part, chuck a uniform tariff on every import from every country.

Put aside the fact that Mr Trump’s claims regarding how much revenue tariffs could actually raise are preposterously overblown. (He often points to a period in the late 1800s as proof that tariffs can fund essentially the whole government. Needless to say, the American government was a heck of a lot smaller back then, and did a heck of a lot less.)

The real point is, we keep getting mixed messages about what the administration is even trying to achieve. Which makes the whole project nonsensical.

The escape hatch, at which a few officials have grasped since Mr Trump announced a 90-day pause in most of the more severe “reciprocal” tariffs last week, is the theory that this whole tariff gambit is just a negotiating tactic, designed to bully other countries into giving the President pretty much whatever he wants.

A form of brinkmanship, then. A bluff, with Mr Trump gambling the world will bow to him before the tariffs do too much damage.

The implication there is that he’s actually in favour of free trade, and is trying to get other countries to lower their trade barriers, and thus has been pretending to love tariffs for decades, including a great many years before he entered politics. I don’t find this plausible.

But say that is the idea. If it is, plenty of people did not get the memo. Thus the spectacle of top Trump administration officials contradicting each other pretty much non-stop.

Here is Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick last week, shortly before Mr Trump announced the 90-day pause: “I don’t think there is any chance that President Trump’s going to back off his tariffs. This is a reordering of global trade.”

And here is Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent during the same period: “If (other countries) come to the table with solid proposals, I think we can end up with some good deals.”

Throw in White House trade adviser Peter Navarro: “This is not a negotiation.”

How can the three most senior economic officials in Mr Trump’s orbit have such obviously incompatible impressions of what the goal is, here? We’re talking about the administration’s central economic policy. These guys are meant to be working in tandem to craft it. It hardly screams competence when they pull in opposite directions.

Add in Mr Trump’s repeated backflips, sometimes altering his policies multiple times within the same 24-hour period, and no wonder everyone is confused.

The negotiation route does have at least one point in its favour: it gives the guy a chance to save face if he decides not to reimpose his higher tariffs at the end of the 90-day pause. He’s got the option to secure a few concessions, claim victory, and tell Americans the previously much-vaunted tariffs are no longer necessary.

Contradiction two: The ‘reciprocal’ tariffs are not reciprocal

In his joint address to Congress in early March, Mr Trump announced April 2 as the date on which “reciprocal” tariffs would go into effect worldwide.

“Other countries have used tariffs against us for decades,” Mr Trump said.

“On April 2, reciprocal tariffs kick in. And whatever they tariff us – other countries – we will tariff them. That’s reciprocal, back and forth. Whatever they tax us, we will tax them.”

OK, sure. That makes some sense. Figure out all the trade barriers other countries impose on the United States, and hit back with equivalent tariffs in the other direction. And if those other countries lower their barriers in response, the tariffs come down.

The problem is that when we reached April 2, and these tariffs were unveiled, they were not reciprocal at all.

The President stood in the Rose Garden with a chart behind him, a list of all the countries he was targeting. Next to each were two columns, with the headings “tariffs charged to the USA, including currency manipulation and trade barriers”, and “USA discounted reciprocal tariffs”.

The first column, it transpired, was a straight-up lie. The administration had not done a thorough audit of all the tariffs and trade barriers and currency manipulation in other countries before calculating its own tariffs in return.

It had, in fact, simply divided America’s trade deficit with each country by the value of its total imports from that country. Any nation that had a significant trade surplus with the US got whacked by extremely high tariffs, while those with trade deficits (like Australia) only copped the baseline 10 per cent.

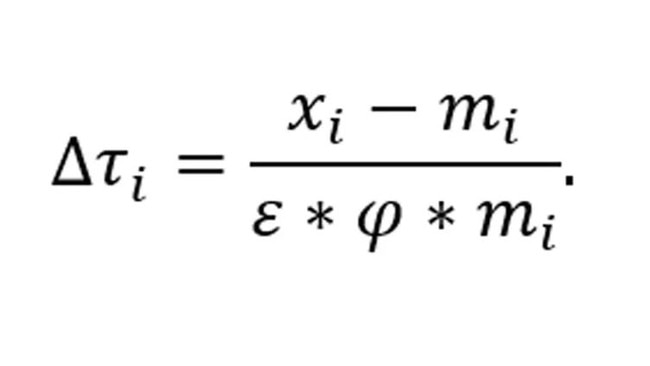

Quite hilariously, if you ask me, the White House released a fancy looking formula full of Greek letters in an apparent attempt to make its approach seem more sophisticated. A formula it had actually botched, it later transpired.

The phi figure below, which represents a measure of elasticity, was plugged in at a value of 0.25 when it should have been nearly 1. The result of which is that, according to Mr Trump’s own formula, the tariffs he announced are about four times too high.

No acknowledgment of that mistake from the White House, by the way.

I digress. The thrust here is not mathematical incompetence, it is logical incoherence. Mr Trump promised tariffs based on other countries’ trade barriers, and what we got instead was a tariff system based on America’s trade deficits. Which is a completely different thing. Except, perhaps, inside the President’s head.

Mr Trump has long believed that, if the US is running a trade deficit with another country, that means the other nation must be ripping America off. Cheating. Not playing fair. This is something he’s been saying for much of his life – it might genuinely be the one issue on which he’s been entirely consistent.

It also collapses under the slightest scrutiny.

We could pick dozens of case studies, but let’s go with the African country Madagascar, where the average daily income is something like six US dollars. That’s a little under $200 per month. Not much purchasing power.

Madagascar is easily the world’s biggest source of vanilla beans; it also exports a lot of cheap clothing. And a fair bit of it goes to the United States.

So naturally, it has a trade surplus with the US. Of course it does. Americans want vanilla, and they want cheap clothing, while those Madagascans living off $6 a day don’t have much use for expensive American products.

According to Mr Trump’s worldview, this means Madagascar is cheating on trade. He reckons those folks farming beans in the African sun are taking advantage of the US.

So Madagascar, this relatively poor country, ends up with a sky-high tariff rate of 47 per cent – or it will, once the so-called “reciprocal” tariffs are reimposed. While richer countries, who could perhaps afford to buy more stuff from America, get far lower tariffs.

What are the people of Madagascar supposed to think, let alone do, when they hear Mr Lutnick telling the rest of the world to “stop picking on us” and “stop treating us so poorly”? When they hear Trump officials’ advice that target nations should either buy more American products or straight up pay the US for the privilege of trading with it? A country with Madagascar’s resources can afford to oblige neither demand.

Then there is the treatment of countries like us here in Australia, which already do what Mr Trump ostensibly wants by running trade deficits with the US, but have been whacked with a 10 per cent tariff anyway.

Let’s get this straight: when another country has a trade surplus with the US, that is a sign of cheating, and of malicious intent. But when the US has a trade surplus with another country, that’s completely fine? If Mr Trump were to consistently apply his own rules, he would argue that Australia should impose tariffs on America, not the other way around.

Again, it is fundamentally incoherent.

Contradiction three: Why were the tariffs paused?

We have heard two different lines, from Mr Trump, explaining why he decided to pause the tariffs for three months a mere day after imposing them.

In the immediate aftermath he gave what appeared to be the honest answer: the stock market and, more importantly, the bond market were in trouble.

“I thought people were jumping a little bit out of line,” he told reporters.

“They were getting yippy, you know, they were getting a little bit yippy. A little bit afraid.

“People were getting a little bit queasy.”

During another brief discussion with reporters on Air Force One, he actually claimed credit for fixing the bond market.

“The bond market is going good. It had a little moment, but I solved that problem very quickly. I am very good at that stuff,” he said.

Mr Trump’s other version of events is that he paused the tariffs because so many countries were calling him, seeking to negotiate.

“Based on the fact that more than 75 Countries have called Representatives of the United States, including the Departments of Commerce, Treasury, and the USTR, to negotiate a solution to the subjects being discussed relative to Trade, Trade Barriers, Tariffs, Currency Manipulation, and Non Monetary Tariffs, and that these Countries have not, at my strong suggestion, retaliated in any way, shape, or form against the US, I have authorised a 90-day PAUSE, and a substantially lowered Reciprocal Tariff during this period of 10 per cent, also effective immediately. Thank you for your attention to this matter!” he wrote online.

That is the line other Trump administration officials have chosen to adopt since, recognising that it’s slightly less embarrassing than conceding he made the markets panic.

It reeks of a cover story. Most of those nations already reached out to the US administration to negotiate before the tariffs came into effect. Why bother imposing them for a few piddling hours, just to get something that was already on offer?

“Many of you in the media have clearly missed the art of the deal,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said during a press briefing afterwards, with what I’d argue we can by now call characteristic sarcasm.

Perhaps she’s right. Few journalists have negotiated trade deals.

An different reading: we just learned that Mr Trump will back down under pressure. We also learned exactly where that pressure should be applied.

He wore a few bad days in the stock market, but as soon as the bond market started to deteriorate as well, the backdown came. And this will be a problem for Mr Trump in future negotiations. Foreign countries are among the major holders of US Treasuries; if driven to seek a way to hurt him, they could theoretically incite another sell-off.

So ultimately, after all this tumult, we’re left with an American tariff policy conceived in pursuit of contradictory goals, which is underpinned by a nonsensical worldview. And it is being orchestrated by a President whose weak spot is now flashing red.

Twitter: @SamClench

Originally published as ‘Incoherent’: Fatal contradictions dragging down Donald Trump’s tariff strategy