‘Does Australia eventually become a target?’: Alarming clue Donald Trump is coming for us

President Donald Trump’s brutal tariffs have sparked global panic – and there’s a terrifying sign that Australia could soon be in big trouble.

When the first shot was fired in what would become the American Revolutionary War at the Battle of Lexington and Concord in 1775, it came to be referred to as “the shot heard round the world”.

With the implementation of the Trump administration’s broadbased tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China, another shot has rung out from the United States that will once again echo across the globe.

And it didn’t take long for Australia to end up in the crosshairs of President Donald Trump’s tariffs, as the imposition of a 25 per cent blanket tariff on US imports of steel and aluminium was imposed.

Australia’s exposure

Despite Australia’s position in a generally quiet little corner of the Pacific and reputation as the lucky country from an aggregate economic perspective, in this instance, Australia is seemingly not immune.

To what degree Australia will be impacted directly or indirectly is unclear. The Albanese government has attempted to convince President Trump to carve out an exception to the tariffs for Australia’s exports of steel and aluminium to the United States.

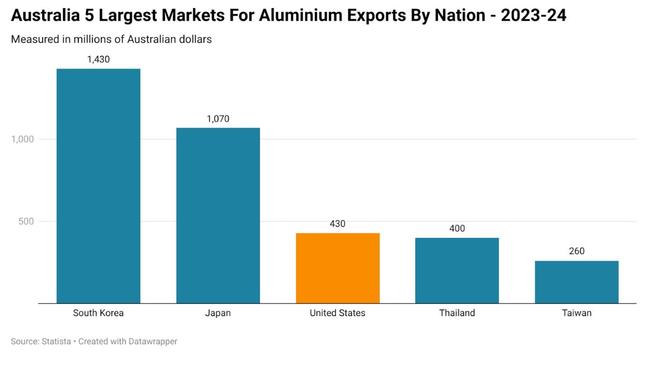

For 2023-24, Australia exported approximately $430 million worth of aluminium to the US. For the 2024 calendar year, Australia exported $639.5 million ($US400.3 million) worth of steel and iron to the US.

In a White House press conference, President Trump was quoted as saying: “It’s 25 per cent, no exemptions, no exceptions. All countries, no matter where it [the steel and aluminium] comes from”.

A few hours later, President Trump had a somewhat different perspective when asked about Australia potentially receiving an exemption. He stated that “great consideration” would be given to potentially providing Australia with immunity, noting that US surplus in trade with Australia was a factor in his decision.

The rollercoaster ride then undertook another twist later that day, with Mr Trump’s Senior Counsellor for Trade Peter Navarro telling reporters: “Australia is just killing our aluminium market” and that “What they (Australia) do is they just flood our (Aluminium) markets”.

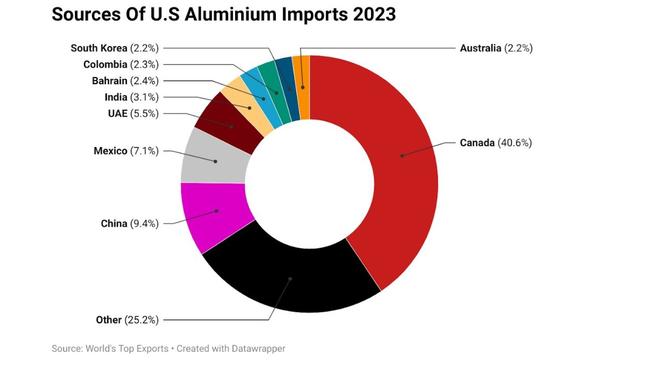

Australia is only the 10th largest import source for American aluminium imports, accounting for just 2.2 per cent of the total. Therefore, it is hard to see how that can be characterised as “flooding” American markets.

In terms of other exposure in the short term, Australia faces a potential hit to the value of our currency and our economy through our strong economic and financial market ties to China. The path of interest rates is also at risk of being altered as the shockwaves and uncertainty stemming from President Trump’s trade actions makes its way to our shores over time.

Australia is not likely to feel any direct inflationary impact from the various trade wars in the immediate future.

But upward pressure on American bond yields as financial markets come to terms with the inflationary impact on the US economy, and by extension those in Australia and around the world, is a risk.

Trump’s motivations and shifting crosshairs

It’s very much an open question if and when Australia and other nations could eventually end up in President Trump’s crosshairs. When asked by a reporter at an Oval Office press conference whether he would impose tariffs on the European Union, Mr Trump responded: “Absolutely”.

With even the closest allies of the United States being targeted by the Trump administration’s trade actions, the question is, what is motivating President Trump to impose these trade actions? Is it purely about Treasury coffers and the US economy, or is there more to it?

Some geopolitics experts have suggested that part of President Trump’s motivation could be reducing Chinese influence within what the United States considers to be its sphere.

In the words of Chinese economy expert Christopher Balding: “I believe people are misreading the different tariff levels. Trump is likely looking to ‘flip’ Canada and Mexico to change their policies on China. That means you want to go big early. China [is] very unlikely to reach an agreement so you strengthen your hand by getting some to flip”.

If curtailing Chinese influence, perceived or otherwise, is one of the primary goals of Mr Trump’s trade actions, does Australia eventually become a target?

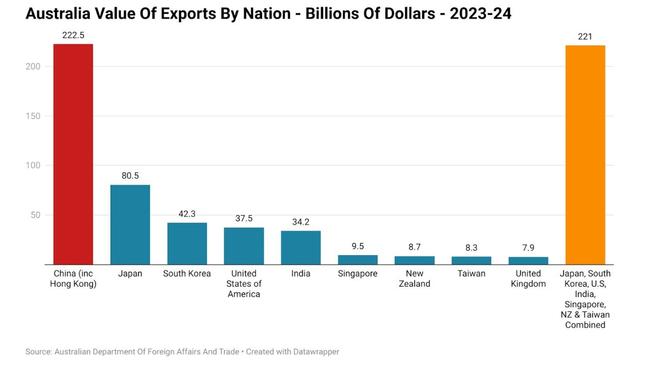

From an economic perspective, Australia is far more reliant on China than Mexico or Canada are, with exports to China (including Hong Kong) totalling $222.5 billion during 2023-24, more than its next seven largest trading partners put together.

Overall, a little over one-third of all Australian exports in 2023-24 flowed to China’s shores.

Australia has also drawn Washington’s frustration previously when dealing with the intersection of Australian and Chinese business interests.

When Australia leased the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company in 2015, then-US President Barack Obama remarked that it would “have been nice to get a heads up” before the deal, revealing that he found out about it from an article in the New York Times.

A silver lining – or a darker cloud?

Whether or not President Trump’s trade actions will be a negative for Australia if they are largely targeted at China over a protracted period is very much an open question.

Assuming all else remains equal, the hit to the Chinese economy and trade flows could see further downward pressure on the Australian dollar and demand for our exports of non-commodity based goods.

The big question is, by what means will Beijing support its economy during this period of challenging circumstances? If the focus is placed on supporting the manufacturing sector and other exporters, potentially at the expense of the traditional growth drivers of the economy such as the construction sector, then that could be a net negative for Australia.

If Chinese demand for steel making commodities such as iron ore and coking coal were to fall significantly, there arguably isn’t the demand from elsewhere to support those particular commodity markets at today’s prices.

But there is another scenario in which a China attempting to come to terms with a new status quo in global trade is beneficial to our nation’s interests.

If Beijing instead opts for the more traditional route it has historically taken to stimulate its economy – construction-based stimulus – then the Australian economy could see a net benefit from the ongoing trade conflicts.

It wouldn’t be the first time Australia was insulated from the impact of globally challenging economic conditions by Chinese demand for our nation’s commodity exports, as illustrated by the Global Financial Crisis and the pandemic.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as ‘Does Australia eventually become a target?’: Alarming clue Donald Trump is coming for us