Victoria’s wheatbelt families fight to stop critical sands mines

More than half of Victoria is covered by mining exploration licenses, while the state’s wheatbelt farming families are fighting to stop projects going ahead.

Victoria’s wheatbelt farming families feel they have been left in the dust as emerging mining projects seed their place across the Wimmera-Mallee.

The region is ripe for the picking for mineral sands and rare earths mining companies, as more than half of Victoria is under exploration licenses.

A national prospectus claims benefits included “excellent” environmental, social and governance practices, a skilled workforce, transparent regulations, and a secure and sustainable critical minerals supply chain.

But farmers say it’s unsustainable and will fail to provide sufficient community benefits, cause severe impacts on mental and physical health, damage prime farmland and injure the region’s grain industry and agricultural production.

The region’s farmers, including St Helens Plains farmer Keith Fischer, are calling for immediate protection across the state’s wheatbelt.

“Landholders should have the same safeguards for land as what we do for water,” he said.

A Resources Victoria spokesperson said Victoria’s projects were in their infancy, but the state had “stringent safeguards” in place.

Mineral Sands, Rare Earths

The federal government listed 55 “investment-ready” critical minerals projects across Australia, while the Victorian government approved 50 new minerals exploration licenses in the past financial year.

Thirty key minerals have been identified for mining, with “economic interest” minerals in Victoria including zircon, rutile, leucoxene, ilmenite, monazite and xenotime.

Mineral sands are typically used in household items, wristwatches, vehicles, solar cells, pigments for paints or plastic, sunscreen or in surgical implants like pacemakers,

Rare earth elements can be used to develop wind turbines and electric vehicles.

Mining Councils Australia Victoria executive director James Sorahan said three projects were awaiting government permits.

“The reason the mines see a future in mining these products in Victoria is in large part due to the renewable energy market,” he said.

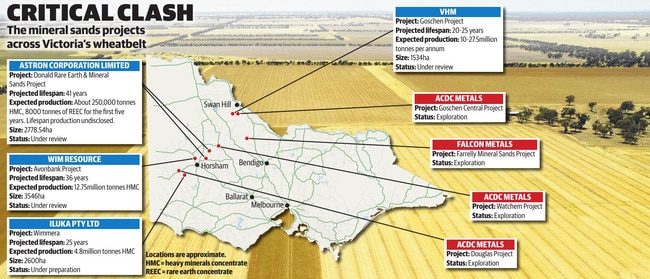

SEE THE FULL SIZED GRAPHIC HERE

Victoria’s Major Projects

The Weekly Times contacted six companies with retention licenses in Victoria to ask about consultation with affected farmers, labour sourcing, and environmental effects statements.

VHM and WIM Resource declined to respond, citing proposals currently under review.

Iluka Resources’ Wimmera Mineral Sands project, which is also under review, earmarked a 2600ha mine for a projected 25 years.

Iluka’s head of rare earths Dan McGrath said the company has mined and processed critical sands for 20 years.

“If executed, the (Wimmera) project will unlock a multi-decade source of light and heavy rare earths as feed for Iluka’s rare earths refinery in Western Australia – ensuring value addition of Victorian rare earth minerals takes place domestically,” he said.

WIM Resource’s Avonbank 3600ha project has a 36-year lifespan, with operations for 24-hours a day, 365 days a year, and identified 16 affected families.

Astron Corporation’s Donald Rare Earth and Mineral Sands project has an estimated 41-year lifespan with 2784ha.

Astron managing director Tiger Brown said it would roughly equate to three farms being displaced in different periods throughout the mine’s life.

“We recognise our project exists within a proud 150-year-old agricultural community that has developed Victoria’s wheat belt, and we take our engagement responsibilities seriously,” he said.

VHM has 1479ha and a 20-year lifespan for its Goschen Project in the Loddon Mallee, and seven dwellings within a two-kilometre radius.

Meanwhile, Falcon Metals Limited is currently exploring a potential Farrelly Mineral Sands Project near Boort.

Falcon Metals Limited managing director Tim Markwell said they were unsure of the deposit’s extent, but currently trying to engage about five farmers.

ACDC Metals is also in its early-stage exploration with three deposits at Watchem, Goschen and Douglas.

Farmers Rally

Several farmer-led groups have formed to address activity in the region, including Mine Free Mallee Farms, Mine Free Wimmera Farms, and Dumunkle Land Protection.

Craige Kennedy’s property is within three kilometres of the Goschen Project, and he is part of MFMF, which is opposed to VHM’s proposal.

The group sought expert and legal advice, with up to $350,000 to engage in the state government EES process.

“We believe this region should be producing food, and the people doing that shouldn’t be negatively impacted by these mines,” he said.

At St Helens Plains, Mr Fischer previously opposed a mining company’s plans to develop a 12,850ha deposit. Its process was put on hold 13 years ago to further assess environmental effects.

He believed farmers should be reimbursed for legal expenses.

“We had 11 landholders who had to pay $3300 each for legal advice. The project didn’t get through … But if it did the expenses would skyrocket,” he said.

Minyip farmer Ryan Milgate’s 150-year-old 3500ha cropping operation neighbours the Astron Corporation’s project, and his concerns centred around rehabilitation success, community health, and accuracy of information.

He believed net community benefit would be “next to nothing”.

“You can’t house 150 people in Minyip or Donald, we’re having trouble housing farm workers as it is. They’ll be drive-in, drive-out,” he said.

Chris Johns’ family were original settlers at Dooen, within WIM Resource’s proposed project. Mr Johns said they would need to leave their family home for the mine’s 36-year life, being 900 metres from the proposed processing plant.

The company’s EES said some dwellings would be displaced over the project course, and financial compensation may not address several landholders’ “strong emotional ties” to their properties.

“We were told we couldn’t live in the house because of the toxic dust, the light, the vibrations and the noise. But if you go to the other side, there’s the Longerenong Agricultural College,” Mr Johns said.

Surrounding the proposed project is wildlife reserve Darlot swamp, Longerenong College, an agricultural hub with grain and hay export companies, and the Johns family property.

They spent $84,000 on solicitors between four families to prepare a submission.

Grain Producers Australia director Andrew Weidemann’s Rupanyup farm is also under a retention license.

“The bigger impacts are around the potential for contamination from dust exposure, the landholders around it, and the community around it,” he said.

Land rehabilitation

Mr Sorahan said mining was the only industry in Australia required to rehabilitate land “back to what it was before it was mined”.

The state government considers mineral sands development to have a “relatively low environmental impact” – when compared with other mining operations and rehabilitation.

VHM’s EES for Goschen said mined land would be unavailable for farming for about five years and would be returned to pre-mining production levels.

But it also said stripping and stockpiling activities could impact soil, and “ultimately impact the agricultural productivity of the land post rehabilitation”.

Mr Brown from Astron, said they removed topsoil and subsoil separately, using GPS-guided machinery and measurements. Post-mining they cap tailings, a by-product of mining, with overburden before returning the soil layers. They expected it to be productive agricultural land 1-5 years after topsoil placement.

Mr McGrath from Iluka said the company had rehabilitated more than 18,000 hectares of land on former mine sites, with 14,000ha of agricultural land. He said three of their four Victorian mining operations were more than 95 per cent complete.

But Mr Milgate said the region’s farmers’ best practice for their land meant “touch it as little as possible”.

“When you’re talking thousands of hectares being mined to a depth of 40-odd metres, how are they going to rehabilitate that? What if they can’t get it right?,” he said.