What you need to know about Victoria’s avian influenza outbreak

Restrictions on bird owners have been eased following an avian influenza outbreak on six Victorian farms, while The Weekly Times can reveal the decision to not kill all emus on an infected property. Here’s what you need to know.

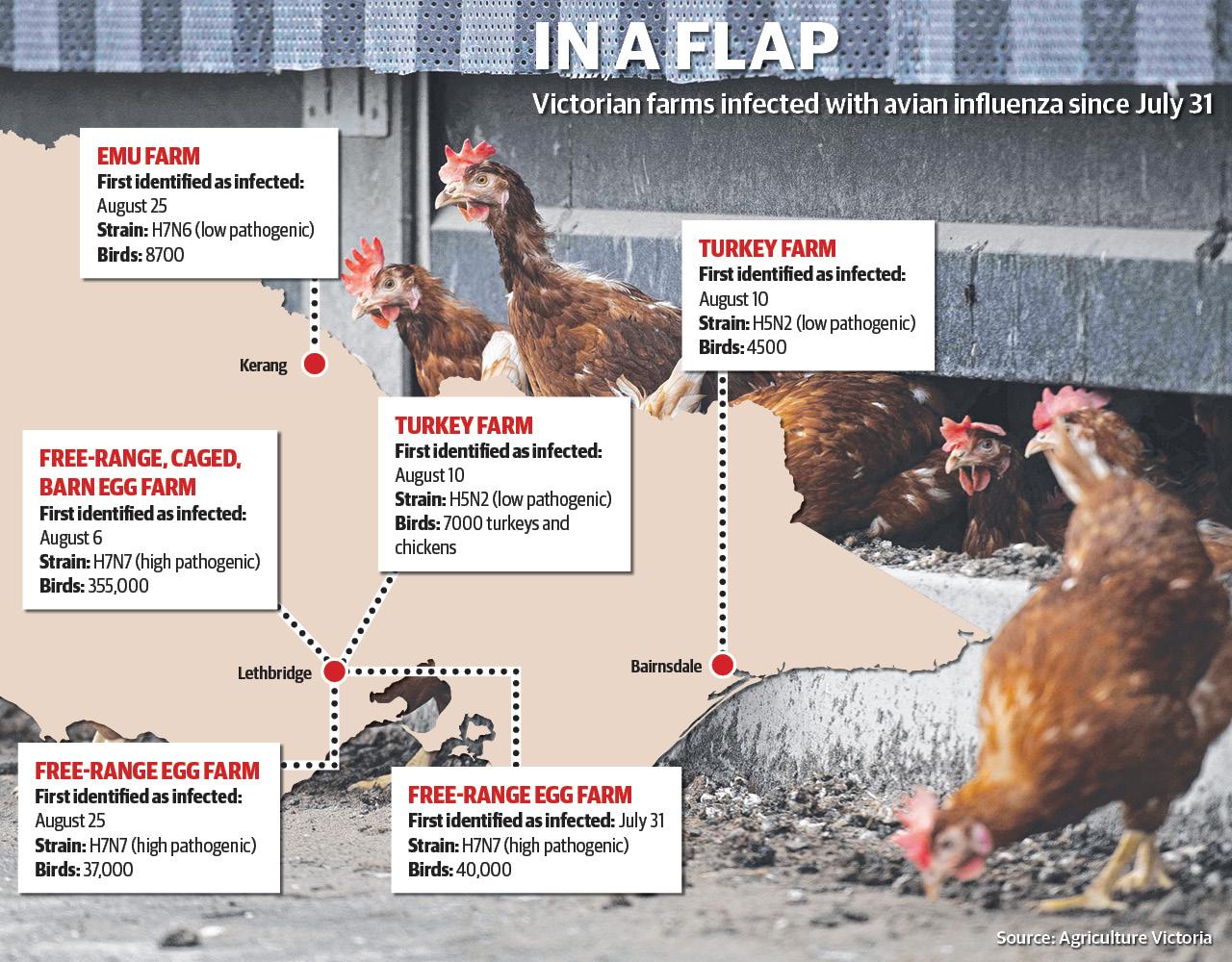

SIX Victorian farms have been infected with three different strains of avian influenza since July 31 and despite the unusual timing, there is no evidence of a link between any of the strains.

About 452,200 chickens and turkeys have been killed to stop the spread of the disease, while 2000 emu chicks and about 3500 one-year-old emus have also been killed. 2000 adult emus from the same property have been spared.

Different strains of avian influenza occur naturally in wild birds and can be carried without the wild birds showing any signs.

“Occasionally the disease spills over into the domestic poultry populations,” Victorian chief veterinary officer Dr Graeme Cooke said.

“We are continuing to investigate the causes of the outbreak in the domestic populations.”

But The Weekly Times can reveal there is no evidence of a link between any of the three strains.

Here’s what you need to know about the current avian influenza outbreak in Victoria.

WHERE IT STARTED

The first free-range egg farm tested positive to the highly pathogenic H7N7 strain on July 31 near Lethbridge. About 40,000 hens were killed to stop the spread of the highly contagious disease.

Since then, two more egg farms in the area have tested positive to the same strain – both farms are operated by ASX-listed Farm Pride Foods.

The first farm tested positive on August 6, which was expected to cost the company up to $23 million in lost revenue. About 355,000 birds were killed, including free-range, caged and barn hens.

Another free-range egg farm, leased and operated by Farm Pride, then tested positive on August 25. At least 37,000 birds have been killed at that site.

A housing order for Golden Plains Shire, where Lethbridge is located, which requires all birds to be kept in an enclosure, was expected to expire on September 6 (originally in place for 30 days) but was extended multiple times. The housing order ended at 11:59pm on Monday 19 October.

“While this is another step in the right direction I strongly encourage bird owners in the Golden Plains Shire to continue to practise good biosecurity and take steps to stop their poultry mixing with wild birds,” Dr Cooke said.

“Our surveillance operations, including swabbing and testing birds, will also continue to monitor the viral load of avian influenza in the area.”

When the original housing order was announced, Australia’s Competition and Consumer Commission gave free-range producers that were forced to house their birds indoors an exemption to continue labelling their eggs free-range for the 30 days.

This exemption was then continued for the extra 21 days.

“We encourage producers to make contingency arrangements for alternative labelling in the event of a further extension of the housing order after 26 September,” an ACCC spokesman said.

TURKEY FARMS

Two turkey farms, one at Lethbridge and one at Bairnsdale, tested positive to the low pathogenic H5N2 strain on August 10.

The Weekly Times understands the Bairnsdale farm had received turkeys from the Lethbridge farm.

About 7000 turkeys and spent hens were killed on the Lethbridge farm and 4500 turkeys killed on the Bairnsdale farm.

EMU FARM

A large commercial free-range emu farm at Kerang was confirmed to be infected with the disease on August 25, but a low pathogenic H7N6 strain. The source is unknown.

On August 28, about 2000 emu chicks from the affected mob were killed and on September 8, 3500 non-breeding one-year-old birds were killed.

The Weekly Times can confirm the current decision by authorities is not to kill all emus on the Kerang farm, meaning there is about 2000 remaining adult birds. Although, there is ongoing surveillance and testing with the decision under constant review.

National policies make allowances for rare and genetically valuable animals.

THE COST OF THE OUTBREAK

Avian influenza response costs in Australia are shared between federal and state governments and industry.

For highly pathogenic avian influenza, government pays 80 per cent and industry 20 per cent, while for low pathogenic avian influenza, the costs are split evenly.

There has been a recent change within the industry, with chicken meat and caged-hen egg producers no longer willing to share the cost of compensating farmers whose free-range flocks have been destroyed.

Agriculture Victoria could not tell The Weekly Times how much the current AI response was expected to cost.

The last reported high pathogenic avian influenza outbreak in Australia was in 2013, in Young, NSW. About 490,000 birds were culled, including caged and free-range birds. The cost of eradication was $3.57 million.

HISTORY OF BIRD FLU IN AUSTRALIA

The last time avian influenza was detected in domestic birds in Victoria was a low pathogenic strain in 2012.

There have been eight high pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks on poultry farms in Australia since 1976, when reports were made available.

These previous outbreaks occurred in commercial poultry farms in NSW (2012), Victoria (1976, 1985 and 1992) and Queensland (1994).

Avian influenza outbreaks have devastated poultry and egg industries overseas.

In 2003, the Netherlands culled more than 30 million birds in order to eradicate the disease.

Eradication cost more than €150 million, which is about $250 million.

SYMPTOMS

Any cases of unexplained bird deaths in Victoria should be reported to the 24-hour Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline on 1800 675 888.

Signs of the disease:

SUDDEN death;

BIRDS with difficulty breathing, such as coughing, sneezing, or rasping;

SWELLING and purple discolouration of the head, comb, wattles and neck;

RAPID drop in eating, drinking and egg production;

RUFFLED feathers, dopiness, closed eyes; and

DIARRHOEA