Three dead in 1884 Little River train smash: How teenage girl caused mayhem

A teenager who caused one of early Victoria’s deadliest rail accidents could not explain how or why. What went wrong?

The reasons behind a fatal train collision on the Geelong line on a rainy night in 1884 came down to two factors – an inexplicable mistake by a teenage girl forced by her father’s dereliction of duty.

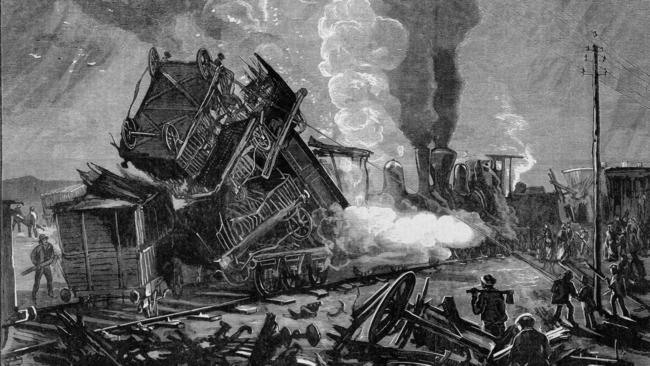

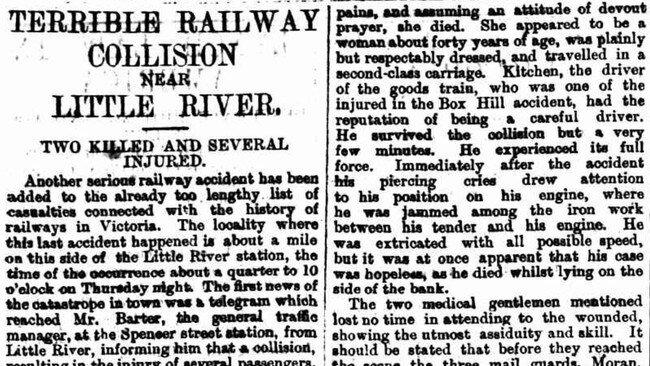

Three people died after a Melbourne-bound passenger train and a Geelong-bound goods service crashed head-near Little River on a dark, rainy night of April 2, 1884.

The passenger service, the evening mail train from Ballarat via Geelong, had just pulled away from the grim bluestone railway station at Little River when the Geelong-bound train ploughed into it head-on.

In those days, only a single track connected Little River and Werribee.

The mail train would normally wait at a siding for the goods train to pass, but was allowed to leave Little River for Melbourne without sighting the goods service that night.

The two trains collided horribly about 800m on the Melbourne side of Little River.

Blinding rain and the rudimentary oil lamps of the day meant the two locomotive drivers did not see each other until far too late.

The line worked on a staff system – a metal rod handed to a driver at a station that signified that the single line ahead was clear. The holder of the staff had the right of way.

Thomas Kitchen, piloting the Geelong-bound train, collected the staff from the porter at Werribee, which let him know that the line was clear up to the siding at Little River.

So why didn’t the mail train wait?

Thomas Biddle, the stationmaster at Werribee, had a decade of exemplary service with Victorian Railways before April 2, 1884.

Biddle worked long hours. Many stationmasters did, and technically none was allowed to leave his post.

But railway chiefs, knowing the enormous hours their people put in, turned a blind eye and allowed others to stand in for them at times.

On the night of the crash, Thomas Biddle slipped away early to attend church choir practice, leaving his 17-year-old daughter Annie in charge.

Annie knew the movements of the trains and was a skilled telegraph operator – the station doubled as a public telegraph office.

The station’s new porter had been there only six days and had only six months’ experience, so Biddle trusted Annie to manage things.

While Kitchen headed down to Geelong with the staff, the Little River stationmaster received a telegraph from Annie that sent both trains to their doom.

She made the horrible mistake of telegraphing ahead to Little River to state that the line was clear.

At the time, a telegraph message could trump a staff.

The telegraph she sent to Little River read: “Please send on 7.10 train. I have staff and will keep line clear, until its. Arrival”.

It’s not known what she was thinking when she did it.

She admitted at a later inquiry that she knew the line was not clear but despite answering 174 questions had no explanation for her error.

Whatever the reason, the two trains hit head-on about 10.30pm.

The two drivers, Kitchen on the Geelong train and Jim Craik aboard the mail train, were killed along with passenger Ellen Johnson. Mrs Johnson, of South Melbourne, was pulled from the wreckage but died beside the line.

Reports from the day vary, but it’s believed at least 20 people were injured, at least a dozen seriously.

Kitchen, who was killed instantly when he was crushed trying to slow his machine, was dreadfully unlucky.

Exactly 16 months earlier, on the evening of December 2, 1882, his locomotive and a another collided head-on at Picnic, a former small railway station between East Richmond and Hawthorn.

Both drivers held their posts until jumping clear metres before impact. Both locos were smashed in up to the funnels and two carriages telescoped together, killing one passenger and injuring 178.

But there was no escape for Kitchen or Craik at Little River.

Their firemen, named McMurtie and Walker, were among those badly injured that night.

One the factors that prevented greater loss of life was the positioning of the guard’s van immediately behind the loco of the mail train, which happened when the train and carriages were reversed in to connect with the locomotive.

It took time before anyone realised Annie’s blunder.

Soon after the Geelong train left, Thomas Biddle returned to the station.

A telegraph from Spencer St soon after asked him to report if he’d seen the mail train. He replied in the negative. He then messaged Little River to see if the mail train had passed.

“The mail train left here a quarter of an hour ago when you gave me the clear-line, signal,” the Little River stationmaster replied.

Annie was dumbfounded.

A relief train with a team of doctors and labourers was summoned from Spencer St.

Conditions were dreadful because of the appalling weather. Despite the rain, the rescue team worked by the light of bonfires.

The workers prized apart the twisted wreckage as the doctors tended to the injured, who were ferried to hospital in Melbourne via the rescue train, which got back to Spencer St about 4am.

An Argus reporter rode down to the scene on the relief train.

On April 5, 1884, he reported: “A little further on a huge black jagged mass stood up against the leaden sky, vividly outlined by the ruddy flames of the huge bonfires which were burning. We were now on the scene of the accident, which was appalling in its extent and horror.

“The time had come for action. ‘Get your lights and litters ready, boys’, was the order, and as the special came to a standstill the willing helpers dropped knee deep into the slush, and advanced at the double along the line of goods trucks, stumbling in the dark over broken timber, wheels, axles, and ironwork of every kind, splintered, twisted, and shivered into atoms on every side.”

Biddle was dismissed from the Victorian Railways and, a few days later, was charged with manslaughter.

He pleaded not guilty at trial and was later acquitted.

The accident led to an urgent tightening of procedures to ensure that telegraphed authorisations for train to proceed on single tracks were no longer used.

In a sad epilogue to the disaster, just a few hours after the sickening crash at Little River, the boiler of a Bendigo-bound goods service exploded just beyond Sunbury station.

The train had just filled with water at Sunbury and was working up a head of steam for the long climb up the Jacksons Creek viaduct, a steep grade between Sunbury and Clarkefield, when the boiler blew.

The fireman was killed instantly, blown from the locomotive and smashed against the supports of the Jacksons Creek bridge. The driver succumbed days later.

Both tragedies threw into stark relief the safety of the Victorian Railways and turned it into a major political issue.

Originally published as Three dead in 1884 Little River train smash: How teenage girl caused mayhem