Grampians fire: soil moisture slumps to levels not seen since 2006 inferno

Low rainfall and high evaporation have driven western Victoria’s soil moisture levels to dangerously low levels, exacerbating the risk of fires.

Soil moisture levels have plummeted across western and southern Victoria, drying out grassland and forests, exacerbating the risk of major bushfires.

The Keetch-Byram Drought Index, which was developed by the US Forestry Service and used by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology to assess the risk of fire, has soared to 103 around Stawell and 133 in Horsham.

Retired Monash University bushfire scientist David Packham said “things get serious once the index gets above 100”.

The drought index is based on how much rain is needed to saturate the soil at each location, to bring it back to field capacity, factoring in both past local rainfall and evaporation.

CFA volunteers fighting the Grampians inferno have already reported conditions are so dry that fire is racing across paddocks where there is hardly any fuel.

Stawell farmer and CFA captain Malcolm Nicholson said fire just whipped across paddocks that crews thought were defendable, given the lack of fuel, leaving just smoking cow pats behind.

“We’ve had just 130mm for the growing season (April-October),” Mr Nicholson said. “Normally we get 250mm to 300mm.”

He said the probe on his property, which measures moisture levels 20cm under the pasture, had been sitting “in the red” since winter.

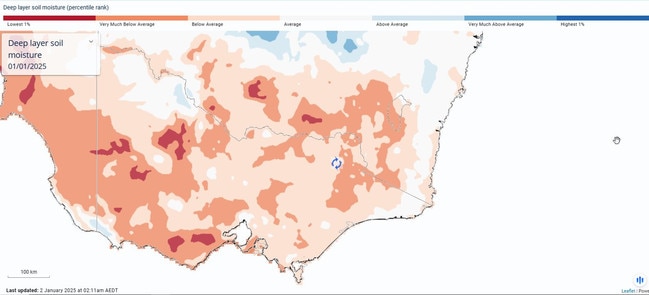

The impact of the long dry is most clearly seen in the BoM’s latest deep-layer soil moisture map, showing levels are “very much below average” in the layer 1m to 6m below the surface and in some areas are at levels only seen once in 100 years.

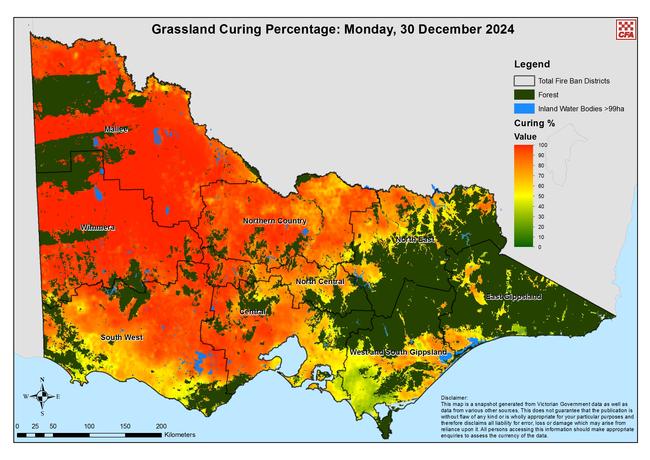

The CFA’s latest curing map also shows most of the state paddocks are completely dried off, due to dry soils and rising summer temperatures.

Dunkeld agricultural scientist Peter Flinn said the district faced its driest year since 2006, when the Mount Lubra fire burnt out 127,000ha of the Grampians, equal to 47 per cent of the national park, with the loss of three lives, 41 houses, 65,598 livestock, plus fencing and 231 farm sheds and other out buildings.

Mr Flinn said history was repeating itself, because not enough was being done to reduce fuel loads: “It’s very frustrating”.

As president of the Howitt Society, Mr Flinn said the group has “pushed as hard as hell to get more fuel reduction burns done”, but “we’re up against the green lobbyists in Melbourne”.

Early last year the Save Our Strathbogie Forest Group took legal action to try and halt fuel reduction burns, arguing Forest Fire Management Victoria should have to gain federal approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act before it lit up any bushland.

At the time SOSF president Bertram Lobert argued prescribed burns should be stopped because they destroyed tree hollows that were home to the Strathbogie Forests’ Southern Greater Glider population.