The full-sized black mock-up of the spacecraft was unveiled for the media at a ceremony in Las Vegas in 1962.

Five astronauts flanked the ship, among them was William “Bill” Dana, who had flown the X-15 rocket-powered aircraft to heights that later were deemed to have technically qualified him as an astronaut.

Another was Albert Crews who had recently replaced a test pilot by the name of Neil Armstrong, who would later become the first man on the moon.

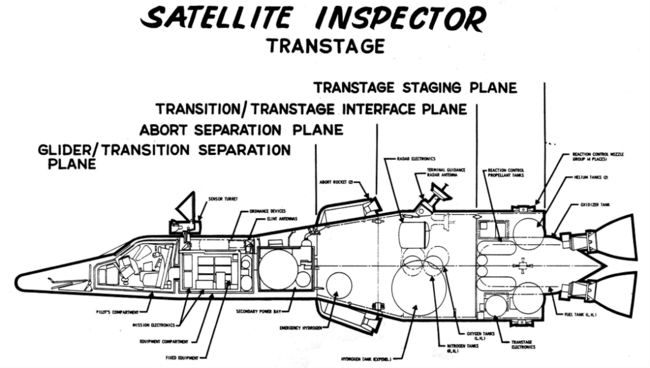

The X-20 was planned for use as a bomber, a reconnaissance aircraft, to deploy satellites or destroy enemy objects in space

The pilots hoped to make their name flying the X-20 Dyna-Soar, which was a Buck Rogers-style winged ship that could be launched from a rocket to fly into space and land like an aeroplane, rather than plummeting back to earth with a parachute.

But it was never meant to be. A year later the project was cancelled.

It seemed like a waste of six years of work and $660 million dollars, but the X-20 program, which started 60 years ago today, left a legacy that would lead to other advances in space technology.

The X-20 had its origins in the German rocket program of World War II, specifically a weapon called the Silbervogel, German for silver bird, designed by Austrian rocket engineer Eugen Sanger.

The Silbervogel was a winged bomber that was meant to be launched from a rocket sled, the fuselage and wings providing lift to carry a pilot and a payload of bombs to an altitude of about 145km, the edge of space.

The concept was that such altitudes would allow it to make fast suborbital hops across the planet so it could bomb targets on the other side of the world, specifically America.

The Silbervogel was never built. In 1944 the Nazis cancelled research on the project and instead went with more conventional long-range bombers.

At the end of the war the Allies captured documents from the Peenemunde rocket range, showing designs for the Silbervogel.

As part of their “Operation Paperclip”, smuggling out Nazi rocket scientists, the US tried to recruit Sanger to work on their rocket project, but he went to work for the French.

However, in May 1945 one of Sanger’s colleagues, Walter Dornberger, who was familiar with the Silbervogel, was one of a group of scientists (including Wernher von Braun) who surrendered to the US.

In America Dornberger worked on guided missiles and what would become the X-15 rocket plane.

But in 1957 he pitched to the US government the idea of developing a boost-glide (one that can be boosted into space and glide back to earth) space vehicle like the Silbervogel.

It could be used as a bomber, a reconnaissance aircraft, deploy satellites or destroy enemy objects in space.

In 1957 the space race was beginning to heat up, with Russia putting Sputnik into space on October 4, and the US fearing that they were lagging behind. Dornberger’s project got the green light.

Named the “Dyna-Soar”, short for dynamic soaring aircraft, it was approved on October 24, 1957.

Nine aerospace companies competed for the contract to build the craft. In 1959 Boeing’s proposal was the winner.

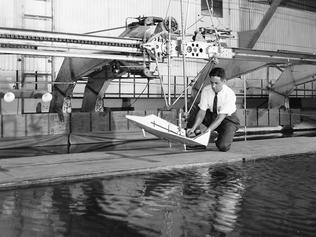

The design took a year of refining before it was finalised and the first mock-ups and models were created for testing in 1960.

It was to be a delta-winged craft, similar in some ways to the space shuttle but about a third the size.

Plans were to boost it into space as early as 1963 aboard a Titan rocket.

A group of elite test pilots were selected to be the first to fly the Dyna-Soar including Armstrong, Dana, Henry C. Gordon, Pete Knight, Russell L. Rogers, Milt Thompson and James W. Wood.

Armstrong made a major contribution to the program by showing that, in theory, the Dyna-Soar could be flown away from the rockets in the event of an explosion on the launch pad.

But both Dana and Armstrong dropped out of the program in mid 1962. Only one pilot, Crews, was recruited to replace them.

The Dyna-Soar was given a public launch at Las Vegas in September 1962.

The air force also made a short film to tell the public about their project “to put a manned, manoeuvrable glider out on the edge of space and fly it back to earth, at will”.

But the successes in the Mercury program, and the pressure to be the first to put a man on the moon, forced NASA and the government to pour resources into other forms of manned space flight.

Also the lack of a clear goal for the program, and the expense, resulted in the cancellation of Dyna-Soar by Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense, in December 1963.

But it was not a complete waste of money.

Dornberger’s ideas, the research conducted into Dyna-Soar’s design and the skills acquired by pilots training to fly the spaceship, helped with the development of the Space Shuttle.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer moves towards autumn what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer moves towards autumn what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.