‘Our identity is on the line’: South Korean adoptees in Australia call for federal inquiry

Shaylee Zerna’s biological mum surrendered her just a day after giving birth. She later learned a horrifying secret – one that’s sparked a call for justice for thousands of Aussies.

For years, Shaylee Zerna struggled looking past her “feelings of abandonment and rejection” when faced with the fact her biological mum had surrendered her only a day after giving birth.

And a deeper dig revealed something further – her history and identity had been deliberately stolen.

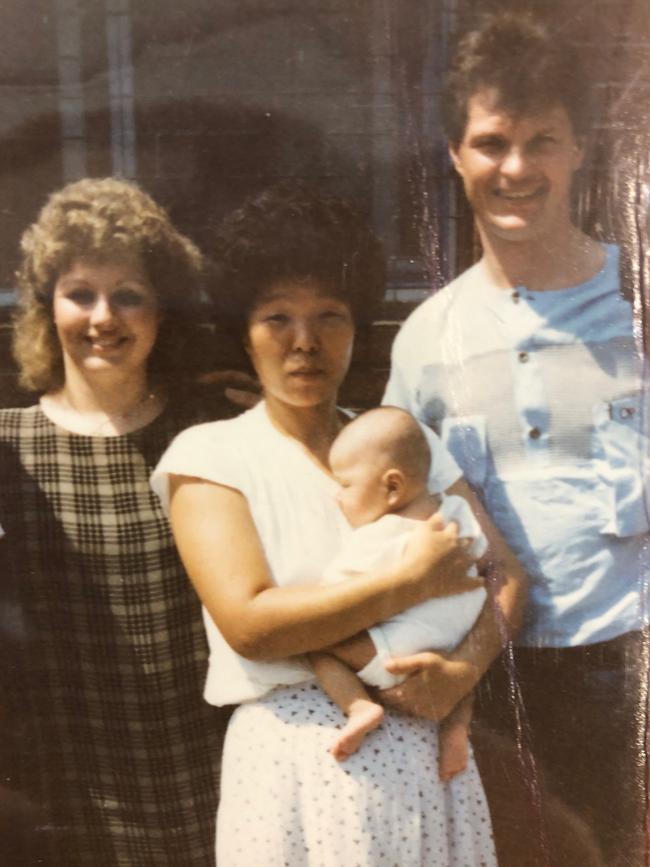

In 1985, Ms Zerna was four months old when she was adopted from a South Korean orphanage by an Australian couple and brought to her new home in Adelaide.

Her new, loving parents never made secret she was adopted and dutifully satisfied her curious questions about her biological parents, her paperwork, and adoption.

For a while, Ms Zerna, now 40, said she accepted her lot in life until curiosity to hear her mum’s side of the story overtook her.

“As a child, it’s hard to understand how a mother can give up her baby but … eventually I looked past my own feelings of abandonment and rejection and I just really wanted to hear my mum’s side of the story,” she said.

However, when Ms Zerna embarked on tracking down her biological parents 15 years ago, she realised that not everything was as it seemed.

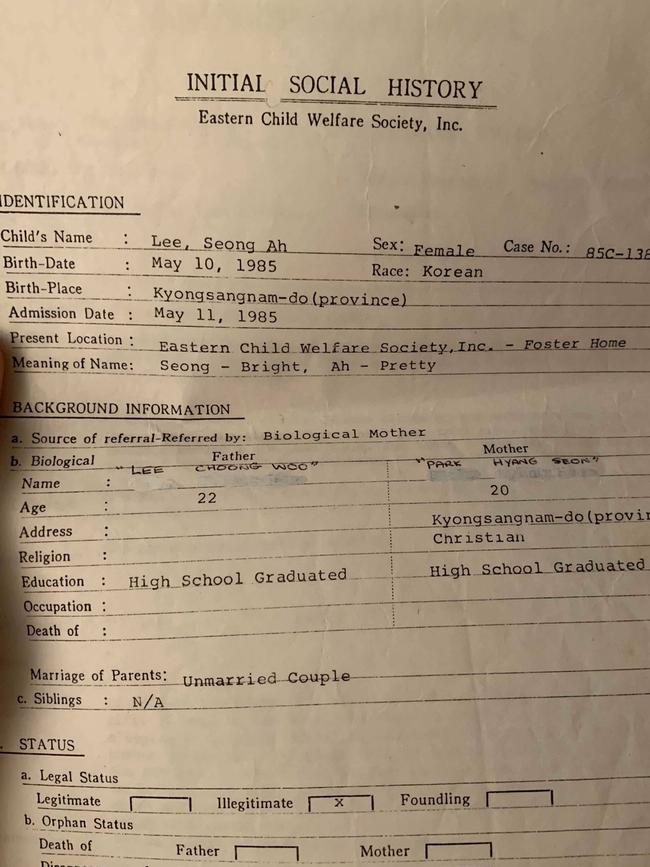

In her adoption documents – provided by the South Korean intercountry adoption agency – her biological parents’ names were “whited out”. Further investigation revealed their Residential Registration Numbers were never in the national database.

There was “no record” of her parents ever existing, she said.

Thousands of Australian-South Korean adoptees are discovering similar gaps, discrepancies or inconsistencies in the paperwork handed out by the intercountry adoption agency Eastern Social Welfare Society (ESWS).

Their concerns were substantiated in a landmark inquiry in March of this year.

The inquiry made clear that Australians who adopted Korean children had no idea of the unethical practices of ESWS.

The South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission report confirmed ESWS practices were rife with abuse, such as forced surrendering, as well as systematic fraud and malpractices, which included falsification of documents.

The inquiry particularly noted that children were falsely documented as orphans when they had known parents. In many cases authorities failed to secure proper consent from biological parents.

Since Ms Zerna learnt of the findings, she has become more determined to uncover the truth and find her biological parents

While in Ms Zerna’s adoption documents her parents’ names were whited out, she was able to decipher the letters by shining a light behind the sheet.

She said this has led to a “heartbreaking” need to scour the internet for people who share her parents’ names and messaging them, in the slim hopes they respond.

“Over the years, I’ve gone and messaged as many people who have my parents’ names,” she said. “But I can’t help feeling a little helpless every time I’m told I got the wrong person or there’s just no reply.”

She’s also done a DNA test, which hasn’t brought her any closer to the truth.

To gain some clarity, she has applied to ESWS to access further documents, but they “wouldn’t engage or give any personal information”.

Now Ms Zerna, who grew up in SA before moving to NSW, has flown to Seoul to hunt for her parents herself.

She left on May 3 to do her own investigations including leaving a sample of DNA with police in the hope authorities can help her trace her biological history.

Although some adoptees have been more fortuitous in finding their biological parents but it has highlighted the contradictory or unethical practices at ESWS.

Kirrily Cogdell-Baird, 42, who was raised in the Riverland and now lives in Queensland, was able to track down her biological mum in a matter of months and met her face-to-face seven years ago.

However, the meeting left her with more questions than answers.

Her mother’s recount differs from the paperwork she has sighted, which had the wrong date of birth, incorrectly recorded her birth place, and wrongly labelled her as an orphan and an illegitimate child.

It also claimed she was an only child – but she met her older sister during the trip.

“What I also found bizarre when I reconnected with my mum was the story of why she surrendered me,” Ms Cogdell-Baird said. “Basically, my mum escaped an abusive relationship with my dad by fleeing the village.

“My mum then found a home by working as a housekeeper for an old lady and the lady’s son.

“Over time, the lady of the house started encouraging my mum to give me up and eventually she agreed … but the catch is that the lady took me to Eastern Social – not mum.

“Of late, I often question this lady, if she was connected to the orphanage, if there was a financial gain to bring me there or how I was accepted without proper signatures.”

The newly formed KADS Connect organisation, representing South Korean adoptees, is calling for Australia to review its role in the scandal.

It wants a national inquiry into Australia’s role into the adoption practices, as well as to recognise the rights of adoptees to access their identity, history and family connections.

For Shaylee, an Australian inquiry would mean “the world”.

“We want Australia to take responsibility for the active role they played in perpetuating the illegal adoption practices or not taking due care of the thousands of babies coming into the country with suspiciously contradicting paperwork,” she said.

“And more than that, this is our identity on the line and our perception of our family and history.”

Australia’s Department of Social Services did not answer The Advertiser’s questions.

ESWS was also contacted for comment.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘Our identity is on the line’: South Korean adoptees in Australia call for federal inquiry