A dangerous but popular swimming hole on the Central Coast is gaining attention with a former caretaker of the site and police speaking about how 18 people have died there since 2010, earning it a grim reputation as a ‘death cave’. Read the tragic story and see historical pictures of the “vortex of misfortune”:

JESSE HOWES MISSING

As the search for 22-year-old rock fisherman Jesse Howes entered its second day in February 2015, Glenn Gifford had a hunch.

After more than 40 years as a National Parks and Wildlife Services (NPWS) ranger, most of which at Munmorah State Conservation Area, it was more than a hunch.

Mr Gifford could sense it and wanted to share his local knowledge with the police officer co-ordinating the massive search as rescue helicopters circled above and dozens of water craft scoured the sea in an ever expanding grid pattern.

He’d offered his assistance the day before to another Chief Inspector but the officer politely declined, deciding it was more prudent in that critical early stage to follow protocol.

But with the hours ticking by Mr Gifford approached Chief Inspector Col Lott who was happy to listen to his plan of putting a GoPro on the end of some conduit and lowering it into a large fissure which runs the length of Snapper Point’s rock shelf.

By that afternoon the search was called off. After all, what’s the point of looking for someone when you know where they are.

It would be another few days before the 4m swell died down enough for a police diver to perform the grim task of recovering the young father’s body.

The story of Australia’s most notorious headland does not start with Mr Howes’ tragic death on February 1, 2015. And sadly it won’t end there either.

Instead it began some 25 million years ago when the area between Caves Beach and Norah Head was the mouth of a massive prehistoric river.

The gravel settled at different rates and factoring in global events such as ice ages, earthquakes and meteor strikes, over millions of years of lithification the rock formed in three distinct layers being the Teralba conglomerate, a coal seam and the Munmorah conglomerate on top.

The layers are clearly visible from the Snapper Point car park.

“It’s still highly erodable,” Mr Gifford said.

“A bit fell off during the Newcastle earthquake.”

Snapper Point cave used to be a blowhole before the landbridge collapsed into the sea hundreds, if not thousands of years ago.

With Australia’s resources sector in its infancy and demand for building products soaring after World War II it was the Teralba conglomerate — the perfectly smooth gravel at the bottom of the cave — that Hayden Frisby and his sons saw an opportunity.

In the late 1950s they erected a large gantry at the top of the cliff and ran steel cables to a hook at the back of the cave.

Using a large flatbed truck with a diesel engine on the back to operate a pulley system, the enterprising miners would lower a Bobcat into the cave and extract the gravel in buckets.

Pebblecrete was the architectural fashion of the day and the small, ocean-smoothed gravel quickly became in high demand.

The problem for Frisby and his sons was they could only operate a few days of the year during extremely low tides and calm seas so despite pulling out 20 tonnes per truck, the gravel saw limited use.

Most notably it was used in the construction of the Bankstown Civic Centre, the fascia of the old Wynyard Train Station and as far afield as Broken Hill.

The Frisby’s permissive occupancy was revoked when the area was earmarked as a State Conservation Area in 1977.

The Munmorah State Conservation Area was gazetted the following year and while the Trust — formed to manage the park — tried to maintain the gantry for its historical significance it was removed for safety reasons in the early 1990s.

SQUATTERS, BEERS AND A GOVERNMENT PARDON

In the 1930s when the Great Depression saw massive unemployment and homelessness, squatters moved into coastal areas and survived largely off the land and sea.

Frazer Beach adjacent to Snapper Point had a natural spring so it became home to dozens of squatters living in tents and later shacks.

Towards the end of the depression Newcastle Council, which then owned the land, wasn’t happy about all the squatters living rate-free in shanty towns so it issued eviction notices.

The story goes the residents of Frazer Beach were all summonsed to Swansea Court to answer charges of trespass and unlawful occupancy.

The only way to Swansea in those days was to walk to Catherine Hill Bay and catch a bus.

Two brothers, Dave and Tom Campbell, were pretty thirsty after the long walk so they stopped in for a few beers at the Catherine Hill Hotel and missed the bus.

The other squatters attended court, were issued eviction notices and went on their way.

By the time Dave and Tom eventually arrived, the court was shut so they went back home and never heard from authorities again.

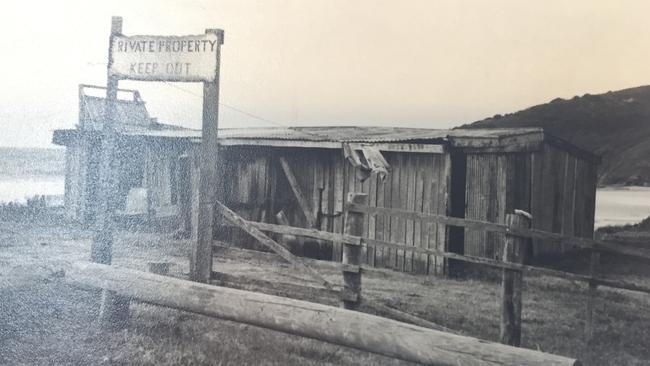

Dave worked for the army during World War II building airfields at Stockton and Tuggerah and managed to save enough money to buy a second-hand shack from Hunter Water which he had transported to Frazer Beach.

Dave and Tom lived in the shack and survived by catching lobsters and fish and hauling them up to the highway for sale. They also did odd jobs until Tom married and moved to Chain Valley Bay.

After the war Frazer Beach was becoming popular for campers so Dave worked for Wyong Shire Council, which had acquired the area in a boundary reshuffle, collecting camp fees and cleaning public toilets council had built there.

When the area became a State Conservation Area, the Department of Lands wanted him evicted but the Trust was adamant it was the only home the now ageing Dave had known.

The land around his shack was surveyed and the Minister for Lands granted him a lease to stay until his death, when the trust would reclaim the site.

Mr Gifford knew Dave from his early days with the Department of Lands in the 1970s and said he and his brother — who was known for his powerful home brew — were real characters.

He said if the campers were making too much of a drunken fuss Dave was known to open a wooden shutter, fire a shotgun in the air and there would be “no more noise”.

“Dave and Tom were instrumental in saving many people who got into difficulty in the surf or washed from rocks or got themselves lost in the bush in those early years,” Mr Gifford said.

In fact, one of the first things the Trust did was run an emergency phone line from his shack to what was then the “Big T Roadhouse Cafe” before it became the Big Prawn.

“It was a PMG line, the previous name of Telstra before the name Telecom, and the phone was a wind up magneto hand set to make the phone ring at the other end,” Mr Gifford said.

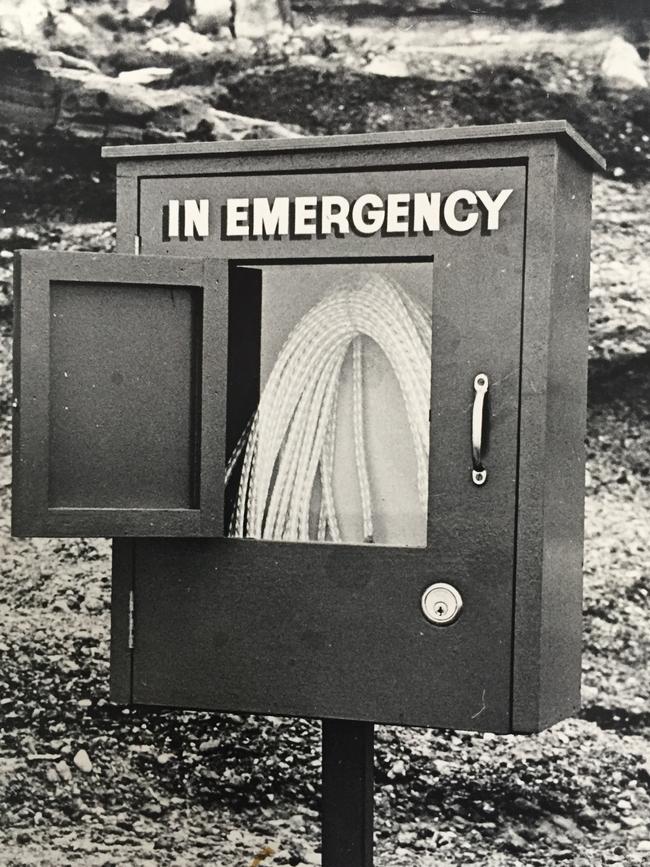

Ironically Surf Life Saving Central Coast is currently considering installing a similar fixed line emergency contact at Snapper Point and has already installed a repeater station at the top of the hill to improve its radio communications.

Old Dave Campbell was diagnosed with cancer and died in 1984. He was in his 70s.

His shack was knocked down not long after and the site is now a picnic area adjacent to the lower beach car park.

In recognition of his services the trust named the main road through the park “Campbell Drive”.

A ‘VORTEX OF MISFORTUNE’

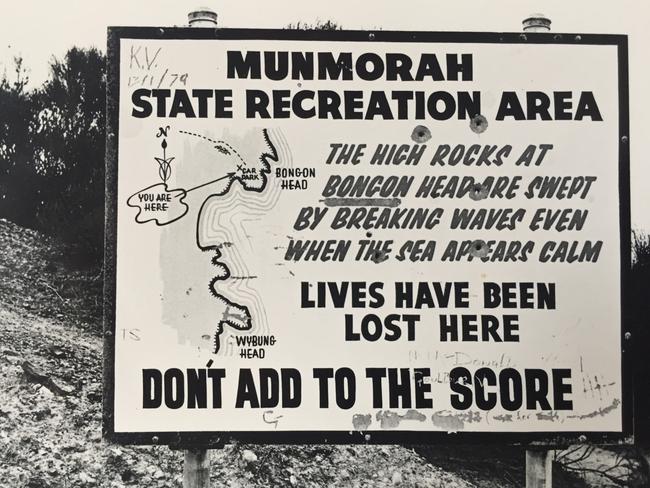

From the early phone line to Dave Campbell’s shack to various signage throughout the years, authorities have tried in vain to prevent needless deaths at Snapper Point and surrounding areas.

One of the Trust’s early members and former president Barry Collier said the Toukley Rotary Club suggested putting up a warning sign in the early 1980s.

However he said one of the club’s members was a lawyer who advised if they put up a warning sign they could make themselves liable by acknowledging the risk.

“So they decided to erect a memorial listing all the names of the people who had died there instead, hoping the penny would drop,” he said.

“In the 10 years of the memorial being up they didn’t have one death,” he said.

Sadly in the years that have followed many more names, like Jesse Howes, have been added to the memorial.

Eighteen people have died in the 3km stretch from Wybung Head to Flat Rock since 2010 — an average of three fatalities a year.

Long serving Police Chief Inspector Rod Peet said the area had a “disproportionate” number of incidents and while some could be explained by weather conditions or poor choices, other fatalities were never understood.

“It’s a vortex of misfortune,” he said.

“What happens to these people and what causes them to have tragedy beset them is actually a mystery.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer moves towards autumn what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer moves towards autumn what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.