Organ donation myths preventing lifesaving registrations in Australia

Flynn O’Malley, 23, is on his third set of lungs after a series of unlucky events. He and other recipients tell why they’re “forever grateful” in a push to get Aussies to register as donors.

An intensive care specialist is imploring Australians not to “rule themselves out” of being organ and tissue donors, after a national survey revealed misconceptions are preventing potentially lifesaving registrations.

Misinformed views like ‘I’m not healthy enough’, ‘I’m too old’ and ‘donation is against my religion’ remain rife among Australians, the YouGov and DonateLife poll shows, creating a chasm between support for donation and actual registrations.

Eighty per cent of the 1032 respondents were in favour of donation, with 58 per cent strongly in support.

But 58 per cent also believed some people were ineligible to become donors. This was not true, with anyone aged 16-plus able and encouraged to register, said Associate Professor Helen Opdam, the Organ and Tissue Authority’s national medical director and a senior intensive care specialist at Melbourne’s Austin Hospital.

“People shouldn’t rule themselves out – leave that to the medical experts,” A/Prof Opdam said.

“We don’t need our organs and tissue after we die, and they would be lifesaving or life-transforming for people on waiting lists and their families.

“We’re also all more likely to need a transplant in our lifetime than we are to die in circumstances where we can be a donor. People don’t say no to a transplant, so there’s a disconnect.”

The survey has been released amid DonateLife’s Great Registration Race, which aims to add 100,000 people to the Australian Organ Donor Register.

RELATED: DonateLife plea for 100,000 Aussies to register as organ donors

World-first kidney exchange program back saving lives after Covid hiatus

The results expose the following misconceptions:

People who have had cancer, are unhealthy, smoke or drink and think they are too old are the most likely to believe they cannot become donors after they die;

The groups Australians believe cannot become donors are men who have sex with men, people from the UK, religious people and people from overseas; and,

That registering to become a donor is too difficult and time consuming.

Anyone from these groups could register, in addition to those who have had Covid or have not had a Covid vaccination, drug users, people with other health conditions, and so on, A/Prof Opdam said.

“Registering only takes a minute,” she added, noting the simple process could be done via donatelife.gov.au, the Medicare app or the MyGov website.

The survey also found men were more likely than women to say something was preventing them from registering (54 per cent compared to 43 per cent), and were twice as likely as the opposite sex to name the liver as the organ they would least likely donate.

The top reason male respondents gave was they didn’t think their liver was healthy enough, causing A/Prof Opdam to suspect Australia’s drinking culture was fuelling this misconception.

Respondents said they were least likely to donate their eye tissue and heart after death, for reasons including it felt “too personal” or made them “feel squeamish”.

A/Prof Opdam urged people to reconsider these views, noting the 1472 Australians who became eye donors last year provided sight-restoring corneal transplants to 2413 recipients. And 36 fewer heart transplants occurred in 2021 than 2020.

She also encouraged the 56 per cent of Aussies who had not told their family they supported organ and tissue donation to do so, as their relatives would ultimately decide whether they became a donor after death.

“Only about 1200 people a year die in circumstances where their organs can be donated,” she said. “And the consent rate from that group is only 60 per cent – that’s not consistent with where we think Australians’ generosity and willingness to donate is.

“The big disconnect is people not making their wishes known to their families. It doesn’t have to be a sombre conversation – it can be over the dinner table, (or) a brief comment while watching TV.”

Australia’s first liver transplant child now at her ‘healthiest’

If Rhonda Natera was able to meet the organ donors who saved her life on two occasions, she imagines she would be “lost for words”.

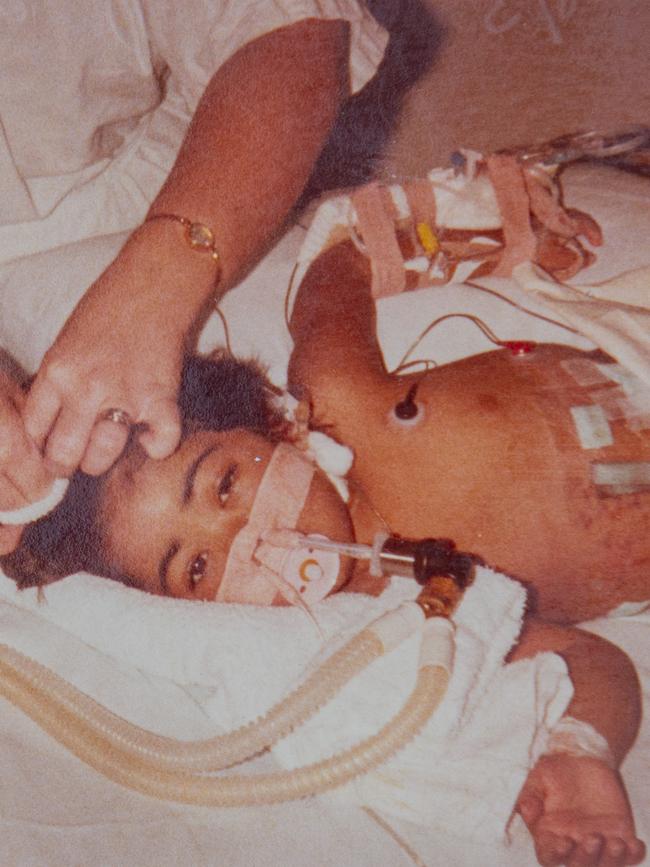

The 39-year-old Brisbane mum has the unenviable legacy of being the first child to get a liver transplant in Australia at age two in 1984.

By 2012, Ms Natera’s transplanted liver had to be replaced and she also needed a new kidney.

This led to a mammoth 26-hour surgery, which was followed by 11 further operations within a week and a half to deal with “a lot of complications”. She then had to learn how to walk and talk again after being bedridden in hospital for six months.

“It was hell,” she said of her second transplant.

“But I’m good now. I’m healthy, I’m doing everything normal people do – and a lot things I couldn’t do before, (like) signing up to a gym.”

Ms Natera was born in Papua New Guinea with biliary atresia, a condition in infants that scars and blocks the liver’s bile ducts.

Her parents, Edward and Brenda, flew her to Brisbane to see specialists who told them “there was nothing they could do, and that had I had two to three months to live, maybe six”.

“They weren’t doing transplants in Australia,” she said.

“I survived past what they said I would and about two years later, my parents got the call saying they were trialling transplants in Brisbane and I would be their guinea pig.”

The first transplant required a 12-hour surgery and left Ms Natera immunocompromised, but gave her a relatively normal childhood. Having recovered from her second, she is now “probably the healthiest I’ve ever been”.

She has spoken to her own children – Maleque, 21, Kyzark, 15, and Leyhina, 8 – about the importance of taking the 60 seconds required to register as an organ and tissue donor, and urges others to do the same.

“They wouldn’t have me if my donors’ families didn’t give me their organs,” she said.

Two-time lung transplant recipient ‘forever grateful’

Getting a new set of lungs at age 16 totally changed Flynn O’Malley’s life.

“It was like going from breathing through a straw to breathing through a very large pipe – it was quite amazing,” the now-23 year old said.

Unfortunately the Adelaide man’s transplanted lungs would only service him for about 4.5 years, before damage from a fire at a Northern Territory cattle station he was working at left him needing another set.

Being diagnosed at age eight with idiopathic pulmonary hypertension, a rare and life-threatening lung disorder, set Mr O’Malley on a path to requiring the first transplant. The need for the second came about after he inhaled damaging particles while trying to free horses from a shed that went up in flames.

“I spent a bit too long trying to put out the fire,” he said. “It caused rejection.”

He didn’t feel the effects immediately. But soon after, when walking up a hill to scope out watering points for cattle, Mr O’Malley’s colleague told him he sounded “asthmatic”.

“That was very alarming – I was the fittest I’d been in my life,” he said.

A check up at the Royal Adelaide Hospital then confirmed the rejection. The hospital’s lung specialists, Professors Mark Holmes and Chien-Li Holmes-Liew, ultimately determined Mr O’Malley needed another transplant, which he received in early 2020.

“The risk (of not getting it) would have been death,” he said. “I would have been lucky to make it past Christmas.”

Prof Holmes-Liew said Mr O’Malley was “one of the few people in South Australia who has had two lung transplants”.

“The outcomes from redo transplants are, in general, not as good as first transplants, so we have to be really careful selecting patients,” she said.

This typically meant young, physically and mentally fit people with plenty of support. This described Mr O’Malley, but he still felt “a large mental toll”.

“Losing that feeling that I had a life (has been hard),” he said. “I’m certainly not miserable though – I’m living, I’ve got a great support network.

“It’s hard to think about how the donor families might be feeling. But I’m forever grateful for both transplants.”

Donor front of mind for World Transplant Games athlete

For heart transplant recipient Josh Lindenthaler, competing in next year’s World Transplant Games will be a way to “honour” the donor who changed his life.

“Yes, it’s something I’ve wanted to do, but I also want to honour them for this gift and make the most of it,” the 39-year-old physiotherapist said.

Just nine months after receiving his new heart in Sydney, Mr Lindenthaler is training to compete in multiple cycling events at the Games, which will be held in Perth in April. Entry is open to all transplant recipients, and donor families and living donors can take part in select events.

The Canberran also plans to complete the sprint triathlon – a 500m swim, a 20km bike ride and a 5km run. But before all that, a half-Ironman event and the Australian Transplant Games are on his radar.

He said none of this would have been possible without his transplant.

An implanted defibrillator and pacemaker had helped Mr Lindenthaler manage his heart muscle disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, for years after his 2008 diagnosis.

But by 2021, his pacemaker could not prevent him from suffering “severe heart rhythms” and joining the transplant waitlist became his only option.

He was placed on the list in July and in September, his mum found him “passed out on the floor” of their home.

“She did CPR for about 16 minutes, as far as I’m aware, until the ambos came,” he said.

Mr Lindenthaler then remained in hospital until he was transplanted in October.

Following a difficult recovery – compounded by the fact his family could not visit and post-transplant rehab was limited due to Covid restrictions – Mr Lindenthaler is now “doing really good”.

He urges Australians to take the minute required to register as organ and tissue donors – “even if they think they’re not eligible”.

“The doctors are there (to determine that),” he said. “One person can save up to seven lives.”

From heartbreak to a ‘miraculous’ diabetes-ridding transplant

A “life-changing” transplant has effectively rid Emily Harvey of the debilitating type 1 diabetes that forced her to abandon a promising ballet career.

The Albert Park mum had two surgeries in 2015 that “popped islet cells from inside a pancreas into my liver”. Those cells then began to produce insulin.

“It was miraculous,” the 51-year-old said.

“I’m still legally classed as a type 1 diabetic. But every aspect of your life is affected by type 1 diabetes, and every aspect has now changed for the better.

“I’m healthier, I can be spontaneous because I don’t have to worry about having enough food or medicine on me everywhere I go.

“It has given me a better quality of life.’

Ms Harvey received the transplant as part of a pioneering research program at St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, in collaboration with St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research.

The program determined pancreas islet cell transplantation could lower or remove the need for insulin injections and stop hypoglycaemic episodes among those with unstable type 1 diabetes.

Even with medication, insulin injections and an insulin pump, Ms Harvey’s diabetes had been “very difficult to manage”. Her diagnosis at age 15 had dashed her hopes of attending London’s prestigious Royal Ballet School, where she had just been accepted, leaving her “heartbroken” and unable to go to the ballet for years.

The impact of her transplant will only be temporary – “they have a shelf life, although nobody knows how long that is,” she says.

“But if my experience helps kids and adults down the track, everything that has gone on has been worth it,” she said. “I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity to have the transplant.”

Ms Harvey urged Australians to speak to their families about taking the 60 seconds required to register as organ and tissue donors.

“Think of how many people, from my one donor, have had their lives totally changed,” she said.