Omicron: How the latest Covid variant is affecting rural healthcare

Rural and regional health care workers are facing staff, equipment and vaccine shortages. Here are the areas most affected.

This coronavirus article is unlocked and free to read in the interest of community health and safety. Click here to see the latest great value offer for full digital access to trusted news from The Weekly Times.

Health care worker shortages are reaching critical levels in NSW and Victoria amid rising coronavirus case numbers, with regional services particularly vulnerable, health care workers say.

NSW Nurses Union general secretary Brett Holmes said NSW hospitals were in “dire straits”, with hospitals already short-staffed. Remaining staff were suffering “exhaustion” and were being asked to cancel holiday leave and work overtime, he said.

“Nurses and midwives are frustrated with the government’s official messaging to the community that everything is OK,” he said.

“Everything is not OK inside our hospital system.”

With Covid cases in both NSW and Victoria increasingly spreading into rural areas, doctors say hospitals may not be able to keep up with the rising number of people needing hospital care.

In NSW, 11,414 new cases were recorded in regional areas in the seven days to Monday – a figure almost double that of the previous week.

In Victoria, 5427 new cases were recorded in regional areas in the seven days to Monday – a figure almost three times that of the previous week.

As of Tuesday there were 1110 people hospitalised due to the coronavirus in NSW, a number that has increased by an average of just under 100 patients per day in the seven days to Monday, while 105 people in the state were in intensive care.

In Victoria, the number of people in hospital due to Covid has increased by an average of 18 patients per day in the week to Monday, with 435 people in hospital as of Tuesday, including 56 in intensive care.

Mr Holmes said, from a staffing perspective, NSW hospitals were already “beyond capacity”.

“When we have the nursing and midwifery ratios that are being reported to me now, we are in dire straits,” he said.

Albury-based cancer specialist Dr Craig Underhill said at the current rate hospitalisation, there was a risk regional patients would not receive the care they needed.

“Regional and remote service are totally reliant on being able to send patients to bigger regional centres or to metro for complex care,” he said.

“The risk is with such a rapid and big surge in cases in the city, that they won’t have the ability to accept patients that we need to transfer, and the transport systems are going to be under pressure as well.”

Southern NSW Local Health District chief executive Margaret Bennett said the region had “everything in place to surge services as and when we need to”.

But Dr Underhill said surge workforces were often a case of “robbing Peter to pay Paul”.

“A surge workforce sometimes means that other services get closed. You might have to close a community-based service to put (staff) into an acute service,” he said

“It is a short term solution, but if you are doing it for months on end, it doesn’t work.”

The Hunter New England region in NSW, which includes an area from Newcastle to Tenterfield and Moree, showed the biggest increase in new cases out of any rural area in the state, with 11,414 (update this – Jan 3 not listed) new cases recorded in the seven days to Monday, up from 6920 new cases the previous week.

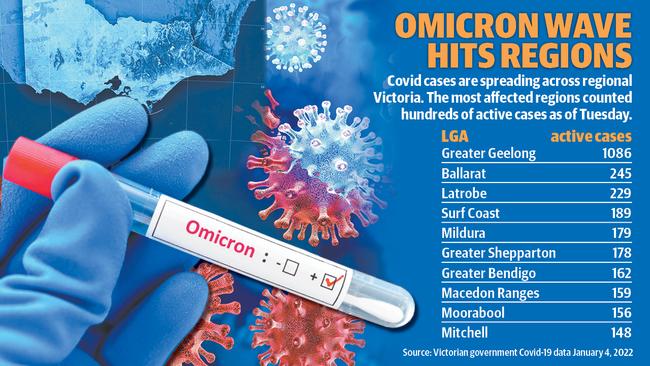

In Victoria, Greater Geelong tops the chart for the highest number of active cases outside a metropolitan area, followed by Ballarat, Latrobe and the Surf Coast.

Nurses

NSW Nurses Union general secretary Brett Holmes said staffing ratios in NSW hospitals during the Omicron Covid wave were some of the worst he had seen.

“We’ve had examples of three midwives for 14 labouring women. We’ve had three registered nurses for 18 coronary care patients,” he said.

“It’s extraordinary. For (maternity) the ratio should be one-to-one. for coronary care, the ratio should be one-to-four or one-to-two, depending on the level of acuity.”

A spokesperson for the NSW Department of Health said the government was investing in an additional 8300 frontline staff, including 5000 nurses and midwives over four years under a $2.8 billion funding boost, with 45 per cent going to the regions.

Doctors

Rural Doctors Association president Dr Megan Belot said rural doctors were juggling a spike in coronavirus testing and trying to manage vaccine delivery alongside already full schedules.

She said question marks were hanging over the provision of rapid antigen tests for rural areas.

“(The government) has said RAT testing will come through the state hubs. We’re very keen to hear how that will be rolled out for rural, small towns where there isn’t state hubs,” she said.

And although an additional four million Australians would be eligible to receive booster shots from Tuesday, Dr Belot said rural doctors had still not received a date for when their booster vaccine supplies would arrive, and could not offer appointments until they had a date.

Albury’s Dr Craig Underhill said one big concern was that, from the first of January, Australians could no longer receive important services via telehealth, just as health systems were coming under increasing pressure to see patients face-to-face.

“Basically, you can’t do a telehealth consultation via phone now. It has to be with video,” he said.

“Sometimes our older population, they struggle with the video. It’s just one more thing that they can’t do because they don’t have (the right technology) or it’s too complicated.”

The department of health was contacted for comment but did not respond by deadline.

Ambulance workers

Victorian Ambulance Union general secretary Danny Hill said fatigued paramedics were facing a “tsunami” of new cases brought on by the Omicron wave, and there simply weren’t enough staff to keep up.

“If you don’t have enough staff in hospitals, and you don’t have enough beds available, there’s nowhere for ambulance crews to offload their patients, so they wait at the hospital in the hospital queue,” he said.

“If you take somewhere like Bendigo, rather than offloading and going straight back to their town, paramedics have to wait at the hospital for sometimes hours at a time before they can get back to their towns.”

“It means when someone calls for an ambulance, the nearest crew may not be available.”

An Ambulance Victoria spokesperson said the agency had recruited 700 paramedics in the last year, which was the agency’s “single largest recruitment in a year ever”.

Mr Hill said the new staff was a positive step, but “it’s still not enough”.

Ambulance Victoria has employed “hundreds” of people in a surge workforce to work alongside paramedics, including volunteers from the State Emergency Services, St John Ambulance, Life Saving Victoria, Chevra Hatzolah, CFA and the Red Cross, the Ambulance Victoria spokesperson said.

Mr Hill said working alongside volunteers could be stressful for paramedics.

“It’s incredibly stressful for the single qualified paramedic because effectively they’re providing all the clinical oversight in some very complex situations,” he said.