Why Bob Hawke was reluctant to give up being Australia’s most popular political figure

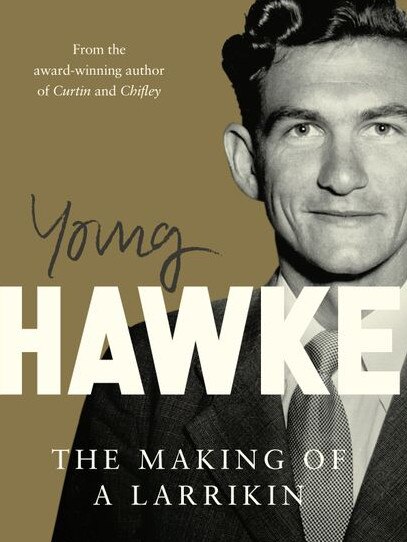

Bob Hawke was one of Australia’s most legendary prime ministers – but as David Day recounts in Young Hawke, wild living almost ended his political career before it began.

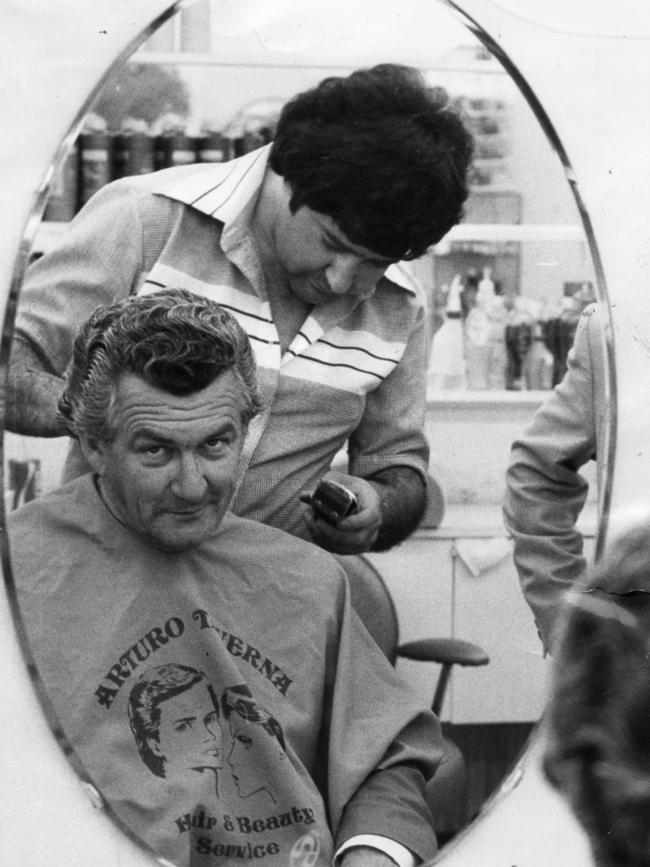

Standing naked in front of the mirror in his hotel suite, Bob Hawke had much to ponder as he lovingly combed his luxuriant mane of hair.

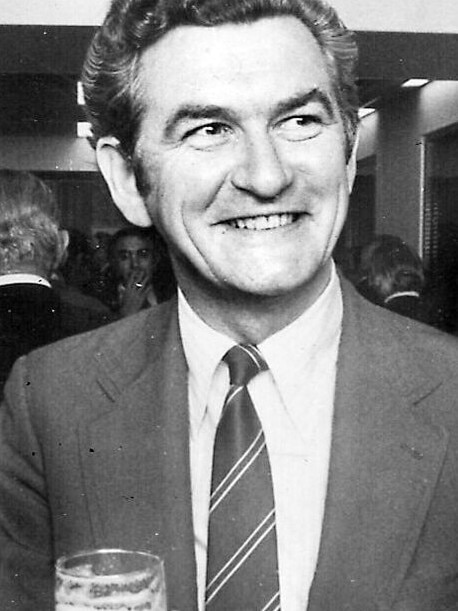

Described as ‘a real peacock’ by one of his lovers, the 48-year-old would comb his hair ‘for five minutes at a time’. He had also taken to dyeing it, and wouldn’t wash his hair in the presence of women for fear they would notice the bare patch that appeared when it was wet.

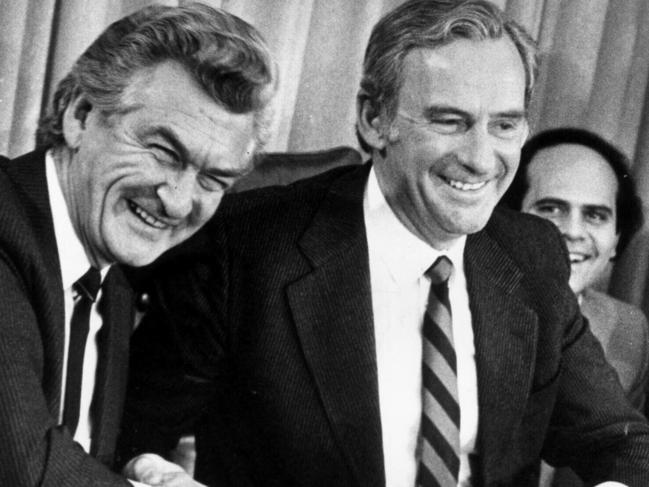

On this occasion on the night of the December 1977 general election, Hawke – then president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions and Federal Labor Party – was at the Canberra Rex with his wife Hazel, the pair having gone there from the tally room with a distraught Labor National Secretary David Combe and journalist Kate Baillieu after the party’s devastating defeat.

Malcolm Fraser remained firmly in charge, holding a massive majority of forty-eight seats. Gough Whitlam had no option but to resign as Labor leader and pass the baton to Bill Hayden. As he contemplated the implications, Hawke wouldn’t have been downcast, since he couldn’t envisage Hayden achieving the massive swing required for Labor to win government at the next election. Nor could he envisage the caucus keeping Hayden as leader once the more popular Hawke had secured a seat in parliament.

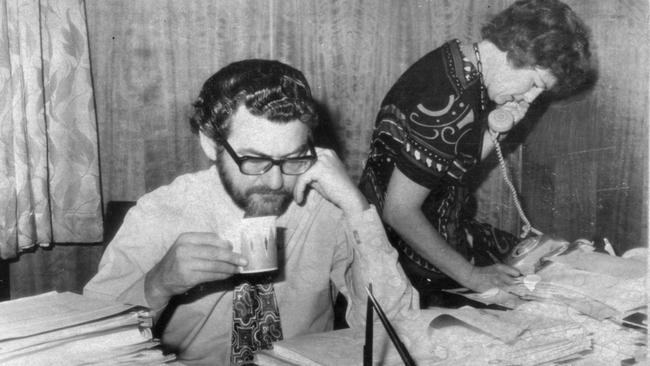

By calling an early election, Fraser had stopped Hawke from mounting a bid for the Labor leadership. It meant more years for Hawke at the ACTU, where his presidency had provided him with unparalleled power, acclaim and celebrity. Although many of his bold initiatives had failed to bear the fruit that he’d promised, his eight years at the top had allowed the ACTU to enjoy a prominence and importance that far exceeded anything that it had had before.

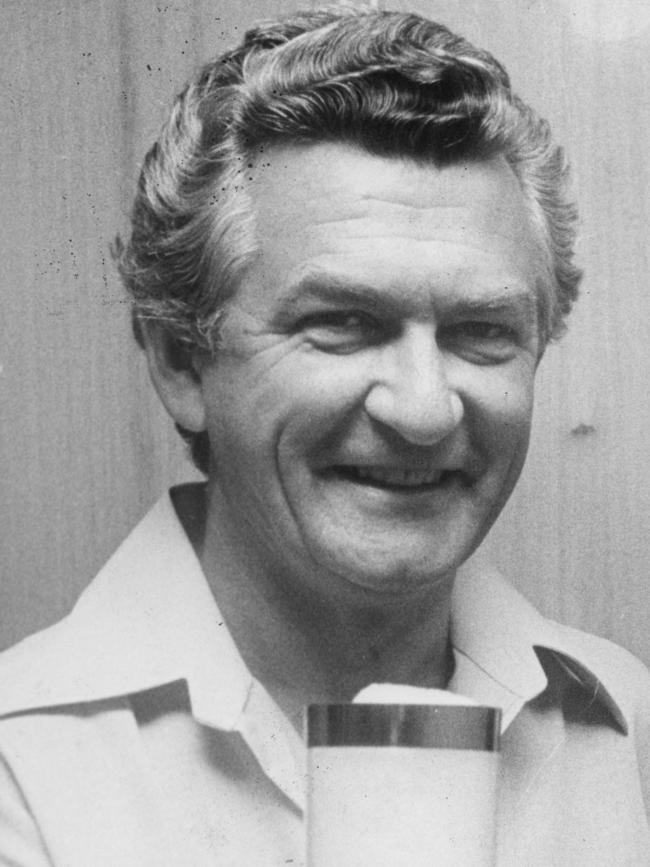

By 1977, a Melbourne University politics course titled ‘Who rules Australia?’ concluded that trade unions had the most power in the country. And such was Hawke’s prominence in the media that some people believed that he, rather than Malcolm Fraser, was the prime minister. Opinion polls tended to bear out that belief. They usually showed Hawke as Australia’s most popular political figure, while focus groups regarded him ‘as the only national leader who is consistently respected and thought likely to handle the job of Prime Minister’.

Such polls helped to keep his political hopes alive and supported the widespread assumption among the public that one day he would be prime minister.

It added to the heavy burden of expectation that his mother Ellie had placed on his shoulders, which was made all the heavier by Hawke repeatedly declaring that his ultimate ambition was the prime ministership, only for him to baulk at repeated opportunities since 1963 to take the leap into politics.

After nearly a decade at the ACTU, Hawke had come to realise the limits to what he could achieve there, and what more might be possible if he became prime minister. But there remained considerable barriers to that achievement: some political and some personal.

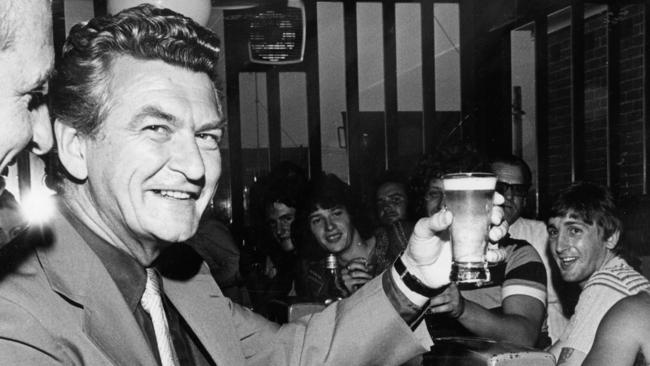

Not least of his problems was his abuse of alcohol. It had almost caused his expulsion from both Oxford and Australian National universities; it had resulted in his admission to hospital for alcohol poisoning; it had produced behaviour that might have been considered criminal; and it had brought regular humiliation upon himself, his family and friends. For years, he’d mostly got away with it in the hard-drinking culture of the trade unions and the Labor Party, and while hobnobbing with some equally hard-drinking journalists. He was open about his drinking problem and promised to give up alcohol if he ever became prime minister. The admission might have been expected to harm his popularity but had the opposite effect. Many voters admired him more for his drinking than for his education or his achievements. ‘Let’s face it, Hawke is a pisspot like us,’ was a response of focus groups, with his drinking being ‘symptomatic of an essential ordinariness … which has strong appeal’. But the bouts of excessive drinking, and the bad behaviour that accompanied it, raised questions about his fitness for high office, not only in the minds of some supporters and journalists but also in his own.

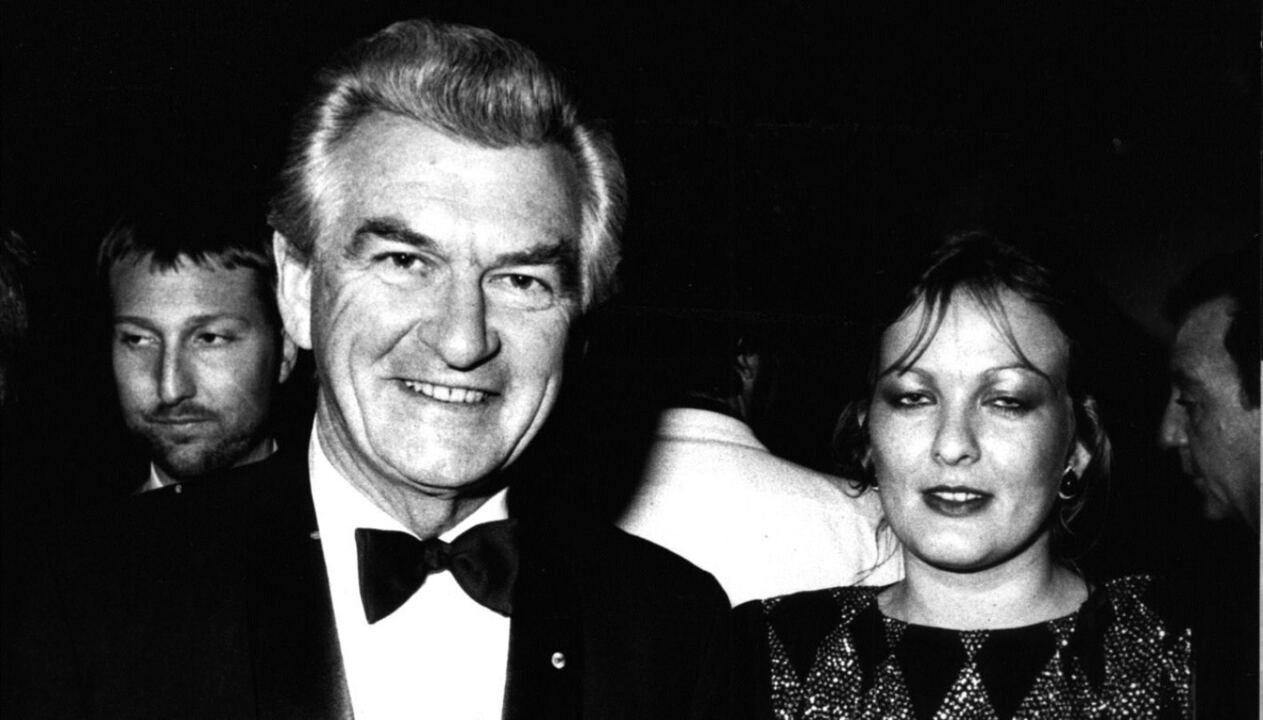

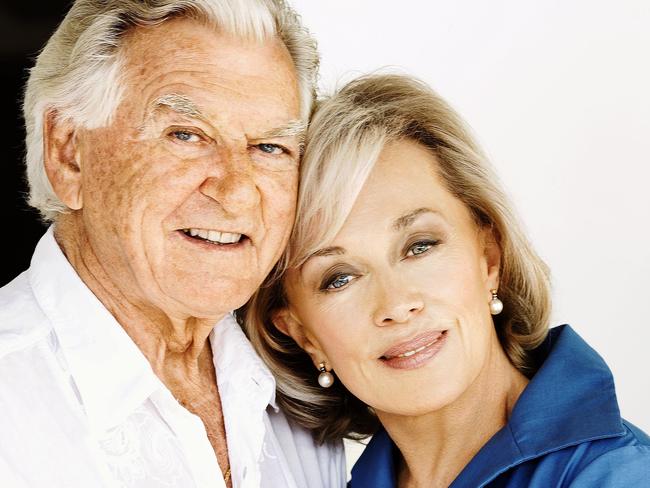

Hawke’s lover and future wife Blanche d’Alpuget was in a good position to see that Hawke was ‘out of control’ by the late 1970s, which she blamed on the booze. His marriage with Hazel seemed irretrievably broken. D’Alpuget claimed that since November 1978, the Hawkes ‘were under the intolerable emotional pressure of having decided to divorce while continuing to live together in the same house, both of them unable to make the final break of physically separating, both of them wracked [sic] by guilt and depression’. Fearing that Hawke was going to divorce her, Hazel consulted a lawyer. But she wouldn’t initiate the divorce. When Hawke suggested in the late 1970s that she move out of the house, she called his bluff and refused. He didn’t have it in him to force the issue. It was a stand-off.

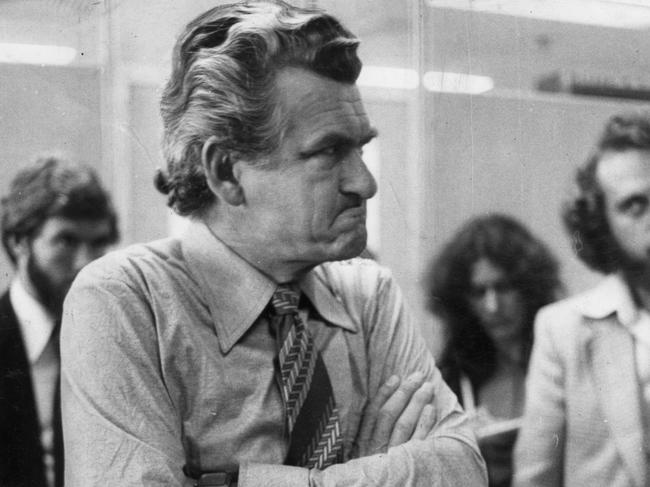

The marital impasse was just one part of a dark time in Hawke’s life. Uncertainty about the trajectory of his relationships was matched by uncertainty about his political future. It was one of several periods in his life when he sank into a deep depressive state, which was made worse by the deteriorating health of his mother, who suffered a second and more severe stroke in May 1978, which put her into a coma. Not expecting her to survive, Hawke made several flying visits to Perth, where Ellie was now confined to a nursing home. The pressure he felt to enter politics became more intense, although it was now unlikely that Ellie would live to see him become prime minister.

Back in Melbourne, he reduced his drinking for several months, only to relapse once again. Friend Col Cunningham recalled the struggles he had trying to convince Hawke to stop his heavy drinking. ‘He would never call it a day,’ said Cunningham, who added that Hawke treated each day as if it was ‘his last day’. After watching the cricket at the MCG, Cunningham found himself taking Hawke off for yet more drinking before finally getting him home late at night. He was ‘looking old, and in a drunken stupor’, recalled Cunningham, who warned Hawke that his drinking would kill him. Hawke was unmoved: ‘I’m a mere nothing – just a spot. What difference if I die?’ His depression was so deep that he welcomed the prospect of death and was relieved when he experienced the symptoms of what he believed to be a brain tumour, which he thought would end his worries, only to have it diagnosed as the effects of flying with a bad cold.

***

Hawke had been stoking the stories about his parliamentary ambitions for nearly two decades. ‘As a true ham,’ wrote journalist Peter Blazey, ‘he fully savours tantalising his audience.’ Holding back from taking the leap suggested that he lacked the courage required

of a great politician, suggested Blazey. There was also a psychological need that was being satisfied. After all, Hawke was already ‘the most popular politician in the country without really being one. He loves the applause too much to give it up now.’

While that was true, the matter was more complicated than that.

Hawke loved the power and the applause that came with being president of the ACTU, but he also loved the bonhomie it brought, whether in the back bar at the John Curtin or addressing workers on a picket line. He much preferred that to living among politicians, whom he considered ‘a much more bitchy, jealous lot’. He liked the financial security that came with being president, on top of which he had stipends from other positions and backhanders from wealthy friends. There was also the freedom he enjoyed as president, with little check on his movements, which would not occur to the same extent if he was an opposition MP.

Then there was his complicated private life: his lover and muse in Switzerland, Helga Cammell, whom he nicknamed ‘Paradiso’ and whose relationship with Hawke was sustained by his frequent visits to the International Labour Organisation; the women in several Australian cities who counted themselves as his lovers, and the many one-nighters during his months away from home each year. His marriage to Hazel might be over, but there was also Blanche d’Alpuget, to whom he had recently suggested marriage. In November 1978, he had told d’Alpuget during a drunken binge of his intention to divorce Hazel and marry her. He’d been tossing up between d’Alpuget and Cammell, when he had a dream during which the women were on a roulette wheel that stopped at d’Alpuget. He interpreted the dream as a sign that he was meant to marry d’Alpuget. She wasn’t sure, though, that she wanted to marry him.

As she later reflected, he was so self-obsessed that he knew little about her and couldn’t even pronounce her surname. Moreover, he was subject to drunken rages that terrified her. This part of his life, which had long fulfilled a deep, narcissistic need to enjoy a succession of conquests and be smothered in love, however fleeting, might change irrevocably if he went to Canberra and became subject to the close media scrutiny that a parliamentary career entailed. Divorce might also cruel his chances of becoming prime minister. For much of 1979, he would wrestle with the decision about standing for parliament and the likely ramifications it could have for his life.

Apart from the implications of divorcing Hazel, his heavy drinking could also destroy his political ambitions, since there would be less tolerance for his wild behaviour in public as a politician in Canberra.

***

As Hawke prepared to make a call on entering politics, at the Labor Party conference in 1979 he was sidelined and outmanoeuvred by the man who most feared him as a rival – party leader Bill Hayden.

At a bar later that day, the exhaustion and the alcohol and his innate anger combined to get the better of Hawke. Surrounded by journalists who kept plying him with drink, Hawke declared that Hayden was ‘a lying c**t with a limited future’ and their relationship was ‘finished’. Hawke was notably absent the following morning when Hayden presented a triumphant leader’s speech that was met with a prolonged standing ovation. Then, when an exhausted Hawke was trying to make an interstate phone call in the conference press office, he was suddenly surrounded by television cameras and radio microphones, which recorded him rounding on the journalists, shouting at them, ‘Fuck off!’

His outburst was played on the evening news. Hawke’s behaviour was regarded by most commentators as having extinguished his chances of a parliamentary career. The headline across the front page of The National Times summed up the general view: ‘Hawke: The end of the road?’ And it might have been the end, had Hawke not been buoyed by his strong self-belief and the messages from concerned wellwishers, including a late-night call from daughter Ros, who told a strung-out Hawke that she loved him, causing him to burst into tears.

The next year, he would become a member of parliament.

This is an edited extract from Young Hawke by David Day: available now, published by HarperCollins.

More Coverage

Originally published as Why Bob Hawke was reluctant to give up being Australia’s most popular political figure