Olympian Emma McKeon teaches children how to swim who live in the slums of Bangladesh

She’s our greatest Olympian and an eight-time world record holder, but Aussie swimming star Emma McKeon may be in for her biggest challenge yet. See the video.

EXCLUSIVE: In a brown, muddy pond in a rural village in Bangladesh, Olympian Emma McKeon watches on the sidelines as kids with big smiles proudly show off their new swimming skills.

Most village families have an open pond in their back yard, used to bathe, wash clothes and, in some cases, fish.

In this one, near Gazipur, north of Dhaka, a bamboo structure has been installed so children can learn to swim safely.

It may look primitive, but UNICEF projects like these are desperately needed. In Bangladesh, of which 10,000sq km is water, 40 children drown every day. It’s the leading cause of death among young kids.

McKeon, 30, is an ambassador for UNICEF Australia, and is visiting Bangladesh to see the work of the children’s charity, in particular its SwimSafe program.

It’s a world away from Wollongong, the NSW south coast city where she grew up and learned to swim, and the pristine Olympic pools where she competed for Australia, winning the most medals for her country – 14, including six gold.

Although she has been briefed on what to expect, it is confronting.

“Seeing it in real life and seeing the kids get in there … yeah, it is a shock,” McKeon says.

“In Australia we are so lucky. Everyone has the opportunity to learn how to swim. Here they learn in ponds, that is nothing like the pools we swim in.”

McKeon’s parents, who have a swim school, started teaching her how to be safe in the water from the age of one. She could keep herself afloat by the age of two.

She says her childhood was wonderful, and she loved growing up by the ocean, in a place which had a country town feel, where “everyone knows each other to some degree”.

Her talent for swimming started to become apparent at 15, and while she swam a lot, it was only after she finished school that she pursued it seriously.

She moved to the Gold Coast – where she still lives – to train, which included nine two-hour sessions in the pool a week, more hours in the gym, plus pilates, yoga, physio and massage.

It’s from sport that she learned valuable goal setting skills, which kept her driving forward. One of her projects, following her recent retirement from competitive swimming, is to create a goals program she hopes will be taught in schools to help Australian children achieve their dreams too.

Meanwhile, her work with UNICEF is also keeping her busy. The aim of this trip is to inspire kids, especially girls, who are living very different lives from children back home.

In the village she meets two grieving parents whose two-year-old boy, Abu Sufiyan, drowned in the family pond, a few steps from his back door, four years ago.

Mum Sufiya, 24, is emotional as she tells McKeon how they discovered their son floating in the water.

Clutching her daughter Adiba, three, she says: “It happened in just a moment. I lost a child and I don’t want any other mother to lose a child.”

Her husband Anis, 28, wants all ponds fenced.

McKeon says their story is heartbreaking and so is the horror statistic of 40 child drownings a day.

“I’m not sure exactly what the stat is in Australia, but one is too many and that’s what my parents have always said because, you know, they have built their lives around water safety and learning to swim and things.”

Later she visits a second program helping girls to swim and surf in the ocean.

It’s not just about water safety skills, it is about challenging societal expectations about girls and women; showing men and boys that females are physically capable too.

“Such a simple thing to us – going down the beach and surfing – is a challenge for these girls,” McKeon says.

REFUGEE CAMP

Tucked away along a narrow, winding path that cuts through the world’s largest refugee camp, past a makeshift soccer pitch where boys play in a cloud of dust, is a surprising find: a beautifully decorated classroom full of giggling girls.

Within the last 20 days, many of these enthusiastic young students, aged 11 and 12, have hit puberty and are now required to wear a headscarf and a niqab, as is the custom in the conservative Muslim Rohingya community that lives in the settlement in Cox’s Bazar, southern Bangladesh.

That these girls are even sitting at desks is a big achievement in itself as deep-seated gender norms, plus a rise in armed gang activity, kidnappings and ransoms in the camp, mean that after their periods start, many are forced to stay at home for their “own safety”.

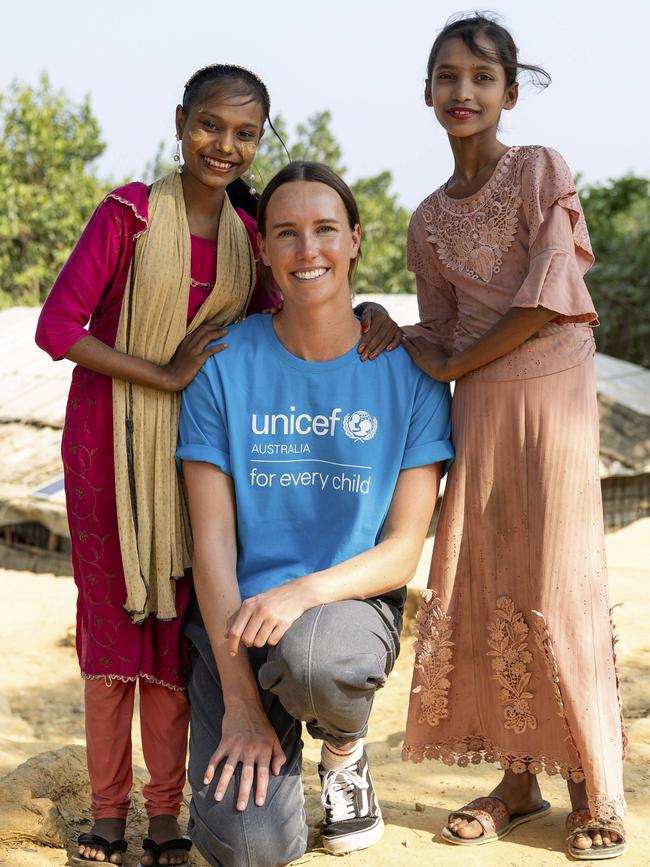

While their faces are hidden, their eyes are sparkling with excitement today, because McKeon has arrived.

This classroom in camp 4 of 33, is supported by UNICEF, one of 3600 across the settlement, providing an education for 300,000 kids. The children take turns to share these spaces.

McKeon is a curiosity to these girls; a strong, female role model who has dominated in sport, which is something that only boys do in their community.

“My name is Emma and I am from Australia. I am an Olympic swimmer,” McKeon says. “Wow, very nice,” they say in English.

The eyes suggest big smiles underneath those niqabs. When the girls speak, their voices are strong and passionate.

McKeon asks what jobs they want to do one day. Their answers, spoken in English, come thick and fast: lawyer, doctor, teacher, pilot, artist.

These girls, who never miss a day of school, dream big too.

However, at the moment there is no access to university for those in the camp. While they receive a certificate to say they have successfully completed every school year, their education is not formally recognised by any other country in the world. If they ever do get out, a lack of official documentation will be yet another barrier to fulfilling their ambitions.

One student, Husnama, 12, says she wants to be a lawyer, to fight for the rights of the refugees.

Her friend Noor, 12,who stands out with her sparkling headband, wants to be a doctor as there are no female doctors, and women and girls are not permitted to “show any feelings to a male doctor”.

McKeon is blown away by these girls.

“They have these hopes and dreams the same way as any other kid,” McKeon says. “But while most Australians have the means to chase them, for the refugees their future is so uncertain.”

She hopes her own story of being a woman who has “chased her own dreams and worked hard at what I wanted” will encourage them not to give up.

Bangladesh, which is two-thirds the size of Victoria but has a population of 170 million, is one of the poorest nations on earth, with problems so vast they can seem overwhelming.

This mega-camp, with 1.1 million refugees, is just one of them.

The majority are Rohingya, often described as one of the most persecuted ethnic minorities in the world. More than 750,000 fled bordering Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, in 2017, following a brutal campaign of violence by the military and Buddhist mobs. At least 25,000 Rohingya were killed and thousands more raped, beaten and burnt.

Half of all refugees are children, 30-40,000 babies are born every year but no one knows for sure because there is no proper birth registration system and, without one, those children don’t officially exist. That’s something UNICEF is working to change.

The standard of living is basic. There are communal toilets and water has to be collected by hand.

They live in cramped, temporary huts on instruction from the government, which does not want the inhabitants to get too comfortable.

These shelters are unable to withstand the frequent floods and fires that sweep through the camps. One fire last year left almost 7000 homeless.

For every square kilometre in the settlement there are 60,000 people. For comparison, in Sydney there are 8660 people per square kilometre and, in McKeon’s home town of Wollongong, just 320.

Most Rohingya want to return to their homeland, but it is unsafe for them to do so. However, inside the camp the security situation has also deteriorated in the last 18 months, with a third of women and girls saying they feel very unsafe, especially at night. Rape, sexual harassment and gendered violence loom large. Male children and youths have been kidnapped by armed groups and taken across the border to fight in Myanmar. Other kids are snatched from the camp and held for ransom by people wanting to make a quick buck.

CHILD BRIDES

The girls in the camp McKeon meets are the lucky ones, as only one in five continues with secondary education in the camp.

The rate of child brides is extraordinarily high both in the camp and across Bangladesh. Half marry under the age of 18, while 15 per cent marry under the age of 15. In some cases, girls are married as young as 12.

“Parents are concerned about the girls’ honour and want to marry them off before that’s lost,”

Head of UNICEF Bangladesh, Rana Flowers, who is Australian, says.

“Poverty is one of the drivers, as are disasters when they strike. It means one less mouth to feed.”

The refugees are entirely reliant on humanitarian aid. Their $US12-a-month (about $20) food rations dropped to $US8 for a while, but are now back up to $US12. Coupled with all the other factors, such as a lack of education, those few dollars could be enough of a financial strain for some parents to marry off their daughters.

At a multipurpose centre in the camp, supported by UNICEF, children like Samira, who at 16 is already a mother, are learning vocational skills.

She talks to McKeon about learning how to service and install solar panels, which are widely used in the camp.

Teaching girls what are considered traditionally male skills is a deliberate move by UNICEF.

“It’s crazy to think that when you meet these girls they’re potentially already married,” says McKeon, who is not married, but in a long-term relationship with singer Cody Simpson.

UNICEF’s work is about preparing these children for life outside the camp, but most of all to give them hope while they wait.

Wealthy countries around the world, including Australia, have been reluctant to offer a home to the Rohingya refugees, although late last year 500 arrived in Queensland.

This year Australia is giving Bangladesh nearly $100m.

Proposals to allow children to study in countries like Australia, even if it means they eventually return to the refugee camp, are being discussed.

“One of our fears here is that they lose perspective of what their possibilities are,” Miguel Mateos Muñoz, UNICEF Bangladesh spokesman, says.

“That’s why visiting icons like Emma can be so fulfilling for children. For those 25 girls that were with her for half an hour, suddenly they’ve seen that there is a young woman with a totally different story than what they are used to.”

CLIMATE REFUGEES

Out of the UNICEF van window, McKeon stares at cows and chickens eating off mounds of litter, beyond which as far as the eye can see is stinking, dank water, and more litter. The depressing mounds of rubbish common across the country are down to a lack of education and poor waste disposal systems.

McKeon is travelling to a village in Samitipara, outside the camp but still in Cox’s Bazar.

It consists of mostly single-room homes, made from bamboo and corrugated iron, but the floors are swept and the beds neatly made.

In the communal outdoor area,McKeon meets Sabekun Nahar, 24, who is queuing up with an urn, waiting to use a recently installed ATM machine that gives out something more precious than cash – clean drinking water.

Around one Australian dollar buys 375 litres of water. There are 12 of these ATMs supporting about 15,725 people in the Samitipara area, just under half the population.

Nahar was born in the village, she is what is known here as a first generation climate refugee. Her parents, along with 40,000 others, left Kutubdia Upazalia in April, 1991, after losing everything in a devastating cyclone and tidal wave that killed 20,000 people.

Access to clean water has become increasingly difficult, due to rising temperatures, drought and irregular rainfall patterns. More than two-thirds of people here rely on unsafe water sources, causing kidney problems, diarrhoea, infections and disease.

Four months ago, a UNICEF-supported climate-resistant desalination plant opened. Operated by solar, it has changed the lives – and the health – of those with access.

“Having safe water has reduced the amount of my hair that falls out and I have less skin diseases and allergies,” Nahar says.

It’s not just the water that is polluted, but the air too.

Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, is home to 21 million people. On the day McKeon arrives it is officially the most polluted city in the world.

The smog is so heavy the sun never manages to break through during the dry season. Stepping out of the airport doors is like entering a sepia-toned Instagram filter.

Several hours outside brings on headaches, itchy eyes and sore throats.

It’s quite easy to see why the pollution is so bad. The roads are clogged with old cars, battered buses and tuktuks all vying for the same lanes, and spewing out choking fumes. The average amount of time someone in Dhaka spends in traffic is three to five hours a day.

People in Dhaka are most affected by this, yet it’s where many survivors of natural disasters and people looking for work have come to start a new life.

DHAKA SLUMS

One young mum hoping for a better life is Brishti. Her beautiful face is framed by her orange and maroon headscarf, and she holds her sleeping baby girl Afsiya in a tiny alley, where only slim shards of dull sunlight can find a way through.

She lives in Korail, where 50,000 people live in less than half a square kilometre. It’s one of five slums in Dhaka.

Also squeezed into the alley is a communal cooking area, where women huddle round one pot of flavoured rice cooking on gas.

Opposite is a family of seven. Here,five-year-old Jannat is visiting. In a yellow-faded tutu skirt and an embroidered orange top, she twirls around the tiny space to the delight of everyone.

Brishti married three years ago and now lives in a single-room, corrugated iron hut with five others, including her husband, who works in a grocery shop, her brother-in-law and mother-in-law.

Discreetly, we ask Brishti how old she is. She tells us 20.

We later discover she is actually 16, which means she was 13 when she got married. Brishti is another one of Bangladesh’s child brides.

Statistically, by marrying so young, Brishti, who left school aged nine, has reduced her life opportunities and that of her child. Brishti’s biggest hope for her daughter is for her “to have an education”.

In Bangladesh, 20 million children marry under 18, that’s almost the population of Australia, says NSW-born Natalie McCauley, chief of child protection for UNICEF Bangladesh.

The crowded slums abruptly give way to a dusty field, where two men play chess on the ground surrounded by a small crowd of spectators. Smouldering litter is the backdrop.

Here girls are playing the national sport of Kabaddi, while others practise self-defence.

Watch the video below.

Getting girls to play sport is a strategic move by UNICEF. It’s as much about building their confidence and providing them with skills to defend themselves as changing the views of boys watching on the sidelines.

“Without these supported programs you wouldn’t see any females here at all,” McCauley says.

McCauley’s a familiar face in the slums and, when she walks around, the street kids come running. There are 3.4 million of them in Bangladesh.

When she arrived five years ago there were two social workers for about 44 million people in the Dhaka district.

Now there are more than 1000 protection workers across the country and she’s hoping to scale that up further.

“We also have a child helpline that was expanded and they get more than 4000 calls a day to refer children to services,” McCauley says. “Last year they rescued over 20,000 children from very violent or abusive situations.”

McCauley’s team can’t fix everything, but they can show up. If a street kid has a wound, they can get them some antiseptic from the pharmacist.

Recently, they got a disabled kid into school, even if she still has to beg in the afternoon.

Later she sheds a tear when two slum girls tell her they want to be social workers when they grow up.

“I am able to change lives every day here and my program in this last year has reached more than 20 million children,” she says.

MALNOURISHED BABIES

“I feel so bad,” says Suldana Razia after finding out her 15-month-old daughter is severely malnourished and needs immediate hospital treatment.

McKeon is looking on as the community health care provider Tatura Akter measures the circumference of Razia’s daughter, Nusiba’,s upper arm. It’s 11.3cm which suggests she is severely underweight.

Nusiba, the youngest of her two children, weighs just 6.6kg. The average weight of a young girl her age is 9.6kg.

“I’m always trying to do good for my child, but somehow she is malnourished,” Razia says. “There are financial issues, I couldn’t provide nutritious food and one of the reasons was the flood because we could not manage the food.”

Razia is at a busy UNICEF-supported clinic in Feni, south of Dhaka, which is in an area which was hit by unprecedented floods in August, impacting a million people. More than 70 people died, homes were swept away, schools and businesses damaged and livelihoods destroyed.

A lack of nutritional food at key developmental stages can lead to stunting and the halting of brain development, from which children never recover.

“The people of Bangladesh are incredibly resilient, proud people and they bounce back eventually,” Flowers says. “But, for children, they miss essential windows that affect them for the rest of their lives.”

She also fears the floods will lead to a spike in child marriages, which lead to girls being at a higher risk of death during childbirth, their bodies not ready to have babies. Their babies are also more at risk. A newborn dies every 10 minutes in Bangladesh.

“I was at a hospital in Cox’s Bazar last week, and the number of babies born under 800g was heartbreaking,” Flowers says. “The majority of them, if any, won’t leave the hospital.”

At a school nearby,Samira, 15, tells McKeon how her family got sick with fevers and her young sister, aged eight, was hospitalised, after they were forced to drink dirty water following the floods.

The water which rose above head height, damaged their house, although she was lucky – others lost their homes completely.

The schoolgirls drew a picture of the scene after the floods where the area looked “like an ocean”. They gave it to McKeon, a treasured keepsake which she still has.

UNICEF helped with the clean-up operation and replaced school books. It also provided clean water and new latrines to residents in the nearby village of Hasanpur.

Divorcee and mum-of-four Afaya Khatun, 30, lives there with her sister, mother Rabeya, 65, and kids, including Afruja, 12. Without an elder male in the family, it’s her responsibility to put food on the table and she’s struggling.

The floodwaters completely submerged her home, destroying all their possessions. The roof still needs fixing. The bed is broken, but they’re making do.

She’s grateful for the new outdoor latrine, which means the family doesn’t have to defecate in a nearby pond.

HOPE

While the Feni floods were devastating, fewer than 100 people died, due partly to the bravery of young people who risked their lives to rescue others.

Siblings Foyez Uddin, 29, and his sister Farhana Akter, 20, a student nurse, were on the frontline during the disaster.

Uddin commandeered boats and saved hundreds of people trapped in buildings, but he also lost a friend helping that night.

Akter, who was at first forbidden from leaving the family home because she was a girl, eventually saved her parents and a paralysed aunt from the rising floodwaters, before helping a woman to give birth on the roof of a house in the middle of the night.

They worked relentlessly for days without sleep. Akter, who is incredibly petite, and unable to swim, survived being tipped from a raft made of banana leaves.

Uddin still carries physical and mental scars from that night.

They’re part of a growing group of young people in Bangladesh who are changing the face of their country.

It was gen Z that helped overthrow the ruling government in August, a couple of weeks before the devastating floods in Feni.

Hundreds died in the political unrest, which saw prime minister Sheikh Hasina and her ministers ousted. She fled to India, amid allegations of mass corruption and crimes against humanity.

Hundreds of murals line the streets, celebrating gen Z’s victory over what they call an oppressive regime.

The young people feel empowered and want real change to happen.

Flowers says McKeon’s visit will have added to that sense of hope.

“She is an incredible female role model. And I think for a country like Bangladesh, where the women, the girls are just too invisible, they’re not allowed out, then having a woman who is strong, dynamic, who’s on a global stage and a success is incredibly inspiring and it brings a great deal of hope.”

McKeon says she’s always wanted to help others, for as long as she can remember and now her success in swimming has given her the platform to do this.

“These children shouldn’t be having to deal with these serious, serious challenges,” McKeon says.

“It definitely makes you so grateful for what we have here, but it just makes me really even more passionate about being able to help these children.”

If you want to support UNICEF’S efforts in Bangladesh donate here: unicef.org.au/emma

News Corp’s journalist and photographer visited Bangladesh as guests of UNICEF.

Originally published as Olympian Emma McKeon teaches children how to swim who live in the slums of Bangladesh