Murder, horror, jail: How Kathleen Folbigg survived a life marred by tragedy from the very start

Even before her mother was stabbed to death in the street and her father jailed, Kathleen Folbigg’s life was a nightmare. A new investigation reveals the full scale of her tragic story.

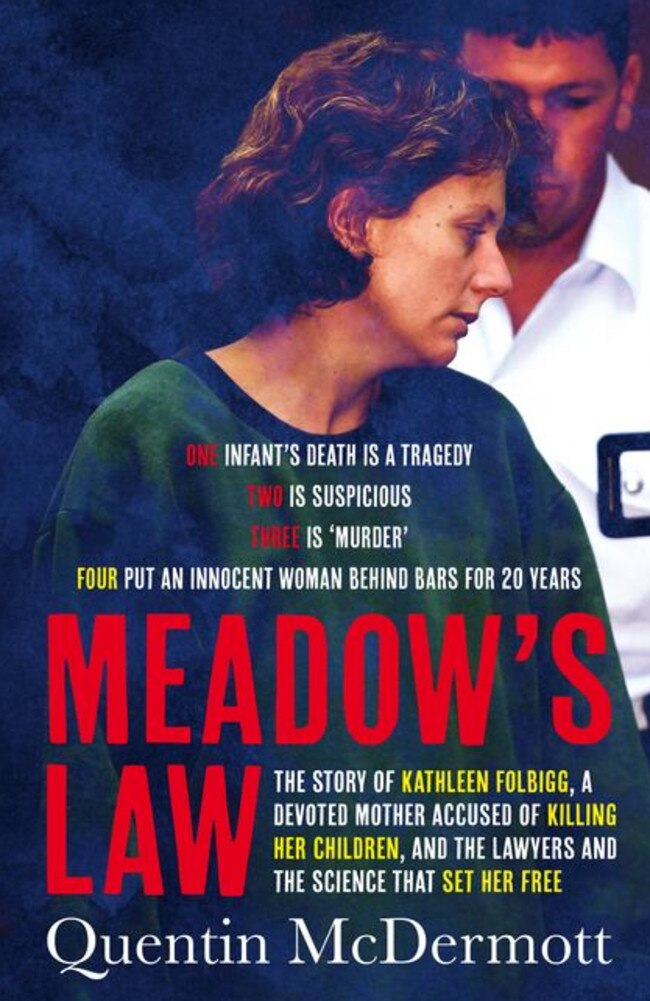

Few cases have gripped Australia like that of Kathleen Folbigg – convicted, then acquitted, of killing her four children. Journalist QUENTIN McDERMOTT, who covered her 20-year fight for freedom, has forensically researched her story for a new book, detailing a life marred by tragedy from the very start.

On a humid summer’s evening in December 1968, in a quiet back street in the Sydney suburb of Annandale, a middle-aged man was seen cradling the blood-drenched body of a woman he had just stabbed twenty-four times in an act of uncontrolled violence.

Thomas Britton, a Welshman who had migrated to Australia years earlier, was a vicious thug – an underworld hitman who worked as a wharfie. The woman breathing her last in his arms was his ‘de facto’ wife, Kathleen Donovan, a factory worker.

As Kathleen lay on the footpath, a shocked neighbour saw Britton bend over and kiss her.

‘I’m sorry darling, I had to do it,’ he told her lifeless body. He turned to the neighbour: ‘I had to kill her because she’d kill my child.’

Britton had done time previously for slashing his first wife in a rage. But Kathleen’s murder was premeditated. Six days earlier, another neighbour had heard Britton tell Kathleen: ‘If I see you on the street alone, I will put a knife between your ribs.’

In a statement Britton gave to the police the night of the killing, he attempted to justify his unforgivable act.

Two weeks earlier, he said, Kathleen had abandoned him and their eighteen-month-old daughter Kathy at Sydney’s picturesque Nielsen Park, where they were having a picnic.

‘I objected to her drinking so much with the child present,’ he explained. ‘She told me she would drink what she liked, when she liked and with whom she liked. I then told her that she wouldn’t.’

Following further argument, he said that she ‘just grabbed her bag and went. She left the child with me.’

That child grew up to be the woman known across Australia as Kathleen Folbigg. And for her, this was the beginning of a nightmare that lasted fifty-five years.

Thomas Britton was jailed. Little Kathy – who appeared to have been sexually abused – was sent to an orphanage then adopted into a stern household where she was treated ‘like a slave’ by her foster mother, according to a friend, until she turned 18 and left.

LOVE AT LAST ... THEN HORROR

It was 1985 and for the young, life in Australia seemed bright. Nightclubs were packed with partygoers with big hair, dressed to impress and dancing feverishly. It was then that Kathy met a young man in a Newcastle club, danced with him and fell in love.

His name was Craig Folbigg.

Craig was tall, good-looking and adept at complimenting Kathy. She described him as ‘extremely charming’, with ‘the gift of the gab’, and she fell for him hard. Craig, six years her senior, was also smitten. ‘I immediately felt attracted to Kathy as she was brash, cheeky, confident, sexy and attractive. We hit it off and started seeing each other on a regular basis,’ he said.

In January 1986, Kathy moved in with Craig. Just eight months later, he proposed, and she accepted. The young couple were able to buy a home in the Newcastle suburb of Mayfield, near the steelworks where Craig was employed.

Kathy was just twenty years old, but she wanted a family of her own. Her close friend Tracy Chapman never had any doubts that she would have children, and lots of them. ‘From my perspective, she was just always destined to be a mother with children around her.’

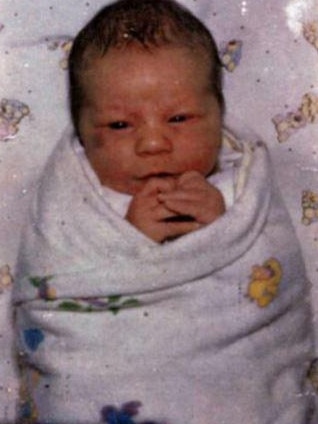

The following year, to Kathy’s great surprise and excitement, she fell pregnant. On 1 February 1989, her first child – Caleb – was safely delivered at hospital.

Kathy described the moment she held Caleb, her heart racing, for the very first time: ‘Seeing him, I just thought that’s what I was on the planet for … And I guess because of being a foster kid and a state ward, and all that sort of stuff, I thought family was supposed to be the ultimate important thing.’

‘IT WAS JUST PANIC’

Kathy’s handwritten diary demonstrated the meticulous way she cared for Caleb, hour by hour. At around 1 am on Monday 20 February, Kathy wrote the words: ‘Put back to sleep?’ and ‘a bit restless’, in her diary, before adding the words ‘Finally Asleep!!’ at 2 am.

About fifty minutes later, she stirred and went to check on Caleb. ‘You can hear babies breathing, they are very definite in how they take a breath,’ she said later. ‘So, when I didn’t hear that, I thought, “What have you done, have you rolled over or something?” And I just placed my hand on his chest and didn’t feel it rise … he just didn’t seem to be moving, didn’t stir, didn’t do anything. So, I flicked on a light and noticed that he wasn’t breathing and then it was just panic from there.’

Kathy said there was blood and froth around his nose and that Caleb was ‘blue around the lips and pale, and for him that was totally unusual because he was a bit like me, he had a dark, olivey skin’. She remembers throwing the covers off him, wrapping her arms around him and grabbing him, scooping him out of the bassinet.

In his own statement made later on, Craig gave a slightly different account:

‘After going to sleep, the next thing I remember is waking up in bed and hearing Kathy screaming: “My baby, something is wrong with my baby!” I jumped out of bed and ran into the sunroom, where I saw Kathy standing over the cot in her pyjamas. She was just standing there, screaming and holding her hands on her forehead.

‘I ran up to the cot and saw Caleb laying on his back and he was still wrapped in the “bunny” rug. He had a blue colouring to his lips around his mouth and his eyes were closed … As I picked him up, I felt that his skin was still warm. As he laid in my arms, I placed my mouth over his mouth and blew into his mouth. At that time, I didn’t know the correct CPR procedures. While I was doing that, I said to Kathy: “Just ring the ambulance.” She was just standing there screaming.

‘Kathy ran into our bedroom, and I heard her talking on the telephone.’

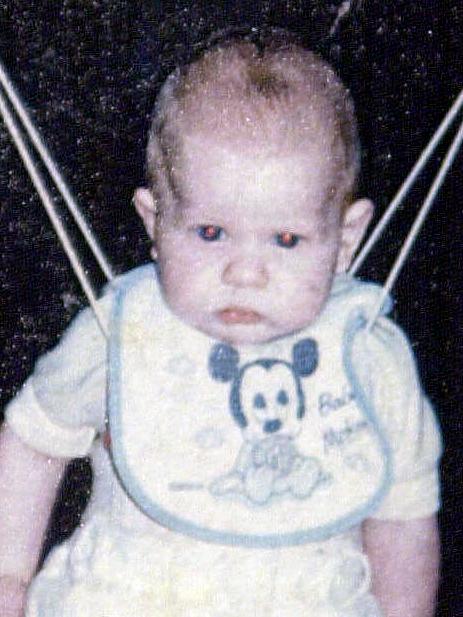

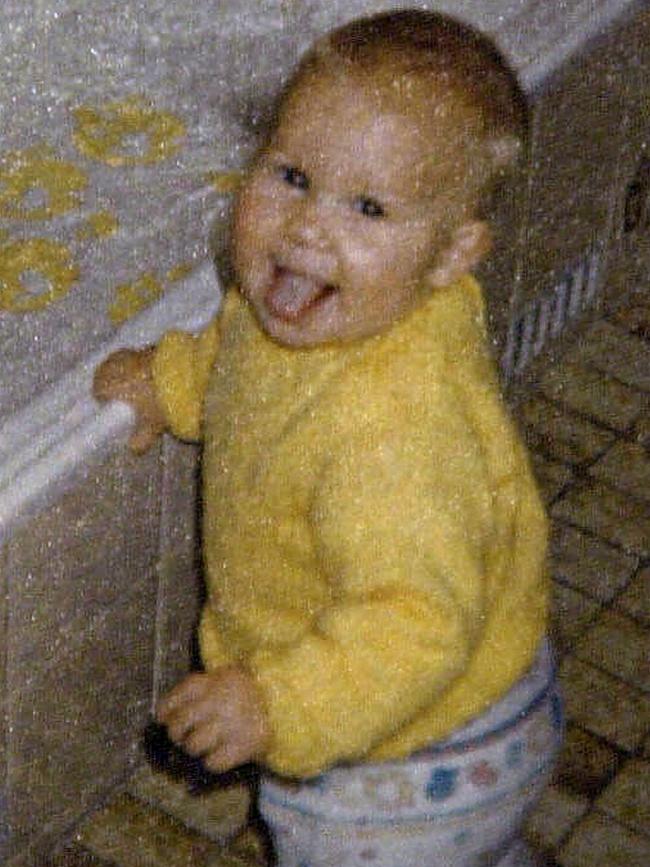

Ambulance officers determined Caleb was dead. Over the following years, Kathleen and Craig, navigating marital highs and lows, would have three more children: Patrick, Sarah and Laura. Each, like Caleb, died suddenly and unexpectedly.

‘FOUR IS F***ING MURDER’

Joe Lavin is a tough, old-school copper who used to run investigations for coronial inquests in Sydney. Joe has a vivid recollection of Monday, 1 March, 1999, the day he received a phone call from a detective in Singleton called Bernie Ryan.

Detective Ryan asked the senior constable to speak to the coroner in Glebe and to Professor Hilton, to give them the name ‘Folbigg’ and tell them that this was ‘number four’.

John Hilton was the pathologist who had carried out the autopsy on Kathy and Craig Folbigg’s third child Sarah, ascribing her death to SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome). He was a memorable character in his own right, a straight-talking Scotsman regarded as one of the very best in the business.

‘I then went into Professor Hilton’s office,’ Joe Lavin says. ‘I just told him I received a phone call and the investigators up at Singleton have asked me to come in and tell you the name Folbigg and number four. His reaction was, essentially: “One is tragic, two is unusual, three is suspicious”, and if I could just use the Prof’s accent, he says: “Four is fucking murder!”’

If this story is true, Professor Hilton was echoing the prevailing mantra of the time – Meadow’s Law – which referred to a statement made by a British paediatrician, Professor Roy Meadow, in a 1989 book he had written on child abuse, that: ‘“One sudden infant death is a tragedy, two is suspicious and three is murder until proved otherwise” is a crude aphorism but a sensible working rule for anyone encountering these tragedies.’

Crude it may have been, but support for the theory grew and it underpinned a number of criminal cases in which mothers who had suffered multiple infant deaths in their families from natural causes were falsely accused and convicted of killing their children.

‘TOTALLY OBSESSED’

After Kathy was charged, a major plank of the prosecution’s case rested on her diary entries.

In April 2003, Prosecutor Mark Tedeschi told the NSW Supreme Court jury: ‘The Crown case is that these diaries contain entries which show her involvement in the deaths of her children, her attempts to deal with the guilt about her involvement in their deaths, her belief that she has grown and matured and learned from what happened to the others and that it will not happen again with Laura, her belief that she is now able to be a proper good mother to this child, despite what has happened to the others, her belief that the dark moods which overtook her with the others will not happen again with this child.

‘Then, later on,’ he continued, ‘her frustrations with parenthood, when Laura was a little older. You will see right throughout both diaries her continuing preoccupation with her weight, with tiredness, with a battle of wills, particularly with Sarah, but also, to some degree, with Laura, her frustrations that she didn’t get more assistance from Craig.’

Mr Tedeschi read out nearly forty extracts from Kathy’s journals in support of the proposition that ‘there were times when she could not abide or cope with the demands of parenthood. She eventually resolved her frustrations, her resentment and her flashes of anger by killing her children. The Crown case is that she was totally obsessed by her own needs, wants and desires.’

To anyone who knew Kathy well and supported her, this was an absurd proposition, but, frighteningly for her, it would be supported in court by two witnesses, who in the past had been among her strongest advocates: her foster-sister Lea and her husband, Craig.

After an extraordinary trial, Kathy was convicted of killing her children – three counts of murder, one of manslaughter – and sentenced to 40 years in jail, where she was targeted by other inmates from day one.

A BAREKNUCKLE FIGHT

On 2 March 2021, an extraordinary event unfolded – one unprecedented in the annals of science and the law.

A new petition was presented to the Governor of New South Wales, Margaret Beazley, calling for Kathy’s unconditional pardon and release.

The petition was signed by two Nobel laureates, two former Chief Scientists, and in all, 90 eminent scientists, medical practitioners and science advocates. Drawn up by Kathy’s legal team, it reflected the outcome of fresh scientific inquiries into sudden, unexpected deaths in children.

This was the first time ever, anywhere in the world, that Nobel laureates had lent support to a petition calling for a convicted murderer’s pardon and release. The campaign – launched in an exclusive News Corp rollout – featured a powerful lineup of science’s great and good, with a clear message: scientific fact trumps judicial speculation and prejudice.

It would turn into a bareknuckle fight between science and the law: on one side, the scientists, who now believed that plausible natural causes of death had been established for all four of Kathy’s children; and on the other, the judges, who didn’t.

In 2023 Kathleen Folbigg was acquitted of killing her children and her convictions were quashed.

More than a year after her acquittal, Kathy still waits to be compensated for her wrongful conviction and incarceration; and as the victim of arguably the worst miscarriage of justice in recent Australian criminal history, she is still waiting to receive an apology.

Her loss has been greater than any other recent victim of a wrongful conviction in Australia. For the rest of her life, she will struggle with the challenge of re-entering the ‘real’ world, with the task of maintaining her own mental health and wellbeing, and with the grief of losing her four precious children; Caleb, with the long, piano-playing fingers; Patrick, the risk-taker; Sarah, the cheeky one; and Laura, so loved by everyone.

She will live forever with the dismay of knowing what might have been.

This is an edited extract from Meadow’s Law: The true story of Kathleen Folbigg and the science that set her free by Quentin McDermott. It will be published by HarperCollins on February 12.

More Coverage

Originally published as Murder, horror, jail: How Kathleen Folbigg survived a life marred by tragedy from the very start