From Sesame Street to the Mozart of maths: Meet Aussie genius Terence Tao

To his family he was little Terry from Adelaide, but to the rest of the world he became known as the Mozart of maths and one of the smartest people alive. See the video.

Summoned by the universal parental suspicion of quiet children, two-year-old Terence Tao’s mum and dad were surprised to discover him using number blocks to teach older kids at a dinner party to count, especially since he’d never been taught how himself.

The little boy was happy to share the source of the new-found mathematical knowledge - he’d learned by watching Sesame Street on television.

It was the first clue Grace and Billy Tao had of the remarkable mind their son possessed.

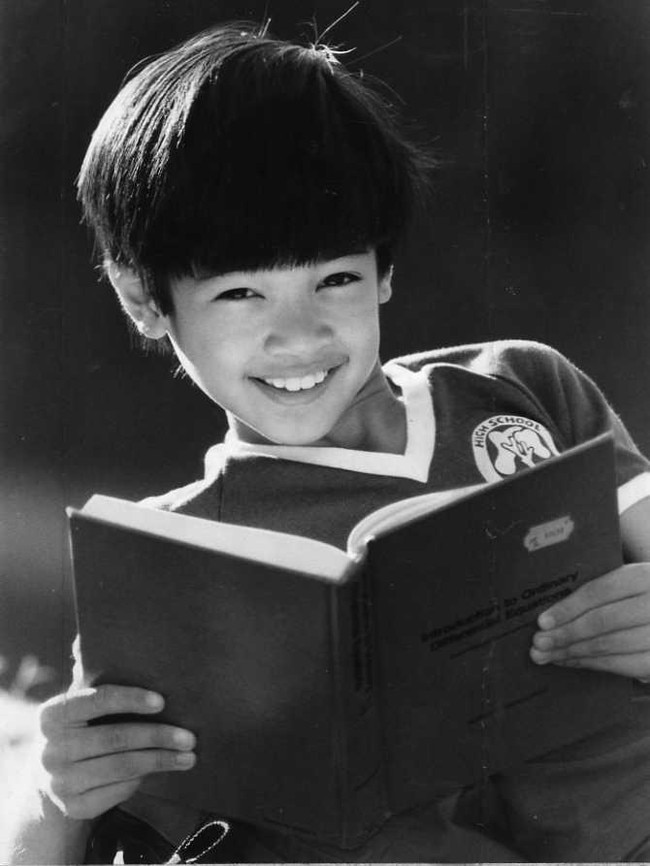

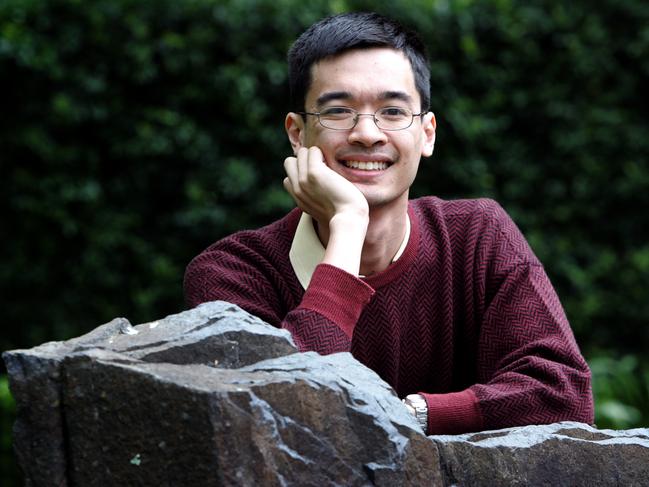

To them, he was their first born, little Terry, a kid from Adelaide with a cheeky grin and shiny black hair.

But he would go on to become known as many other things to the rest of the world - the Mozart of maths, the smartest person alive, Dr Tao, a Fields Medallist, teacher, mentor and genius.

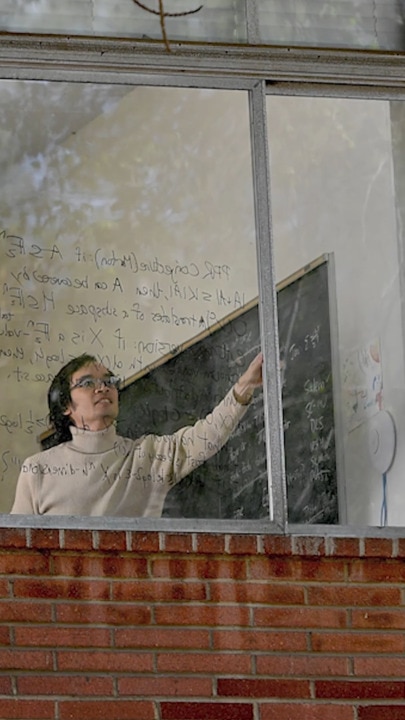

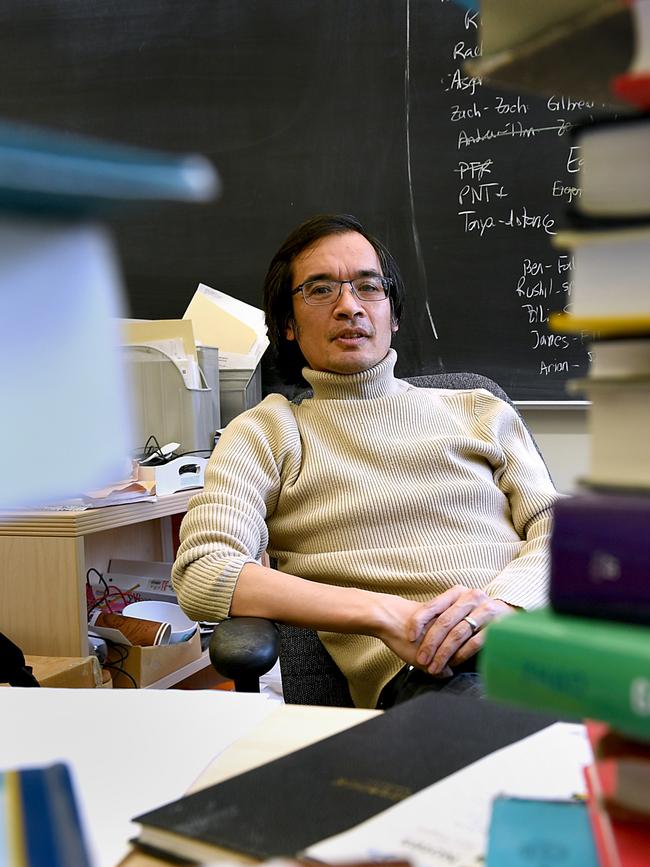

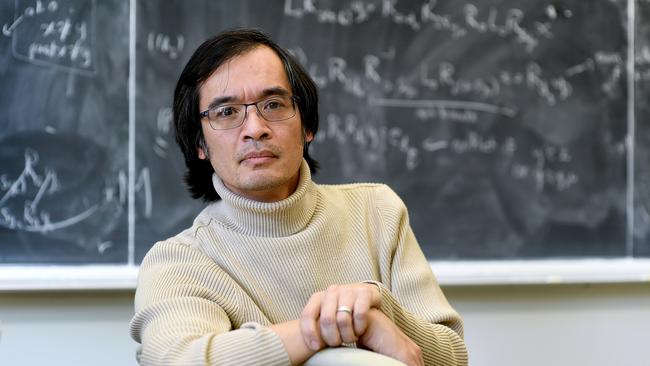

The word genius causes the adult Dr Tao to squirm during an interview in his office at the University of California in Los Angeles where he became the institution’s youngest ever professor at age 24.

He scrunches up his face and waves his hand as if trying to swat the description out of the room.

It’s that modest attitude that has contributed to his status as something of an academic rock star, another label he’s clearly uncomfortable with.

He would have every reason not to be humble because he is, by any definition, a genius.

Just three years after learning to count while watching Big Bird and Count Dracula in his family’s lounge room in the late 1970’s, he went on to complete the primary school maths curriculum at age five.

He was taught by his mother who had been a teacher in Hong Kong prior to immigrating to Australia before Terence and his brothers were born.

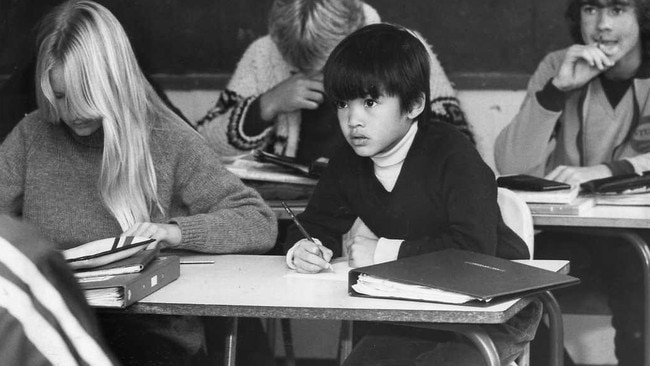

He skipped multiple grades at Bellevue Heights Primary School, started taking Year 11 maths classes at age seven, and began high school full time at eight.

A photo published in the Adelaide Advertiser in 1983 shows the tiny figure in a classroom of Blackwood High School kneeling on his seat to see the chalkboard, surrounded by students twice his age and stature.

The headline reads: “Tiny Terence, 7, is a high-school whiz’.

“When I was too rowdy as a kid, my parents would give me a math workbook to calm me down,” he says.

“I struggled a lot with fuzzy, undefined tasks, like in English class we were asked to write something about our home and I didn’t know what to do, I just wrote a list of all the rooms in the house, and the contents of each room.”

By age nine, he was taking a third of his classes at Flinders University where he went on to graduate with a Bachelor of Science in mathematics with honours at 16, before receiving his Masters at 17.

After being encouraged by an adviser to continue his studies abroad, Dr Tao moved to the United States where he undertook his PhD under adviser and renowned mathematician Elias Stein at Princeton University.

He still returns home to Australia for holidays with wife Laura, daughter Madeleine, 13, and son William, 22, where he enjoys a dip at Glenelg Beach and a packet of Burger Rings - although they don’t taste as good as he remembers from his childhood.

Google Terence Tao and some of the most common results are articles describing him as the smartest person alive, with an IQ of about 230 - anything above 140 is considered genius territory.

It’s a label Dr Tao rejects, describing the IQ system as a “pop culture thing”.

“No one puts the IQ test on their CVs,” he says.

“It doesn’t help me solve any more math problems.”

Last year South Korean YoungHoon Kim reportedly recorded an IQ of 276.

Dr Tao is widely regarded as one of the world’s greatest mathematicians and has collected some of the most prestigious accolades in academia, including the Fields Medal at age 31, often described as the Nobel Prize of maths.

While many mathematicians specialise in a singular niche field, Dr Tao is renowned for working across a wide range of disciplines including harmonic analysis, partial differential equations, analytic number theory and combinatronics.

His Field Medal citation referenced his broad field of work, describing one achievement as “...akin to a leading English-language novelist suddenly producing the definitive Russian novel”.

Dr Tao’s work has helped make enormous advances in understanding the properties of prime numbers, removed barriers in the study of wave theory and delivered new insights into the Schroedinger equation.

One of the algorithms he worked on helped significantly reduce the time it takes for MRIs to be done.

Growing up, Dr Tao wasn’t aware mathematics was a profession he could pursue until he encountered former Queensland professor Basil Rennie who acted as a mentor.

The pair would have tea and biscuits while discussing and solving maths problems.

“I had thought that math was just somehow, some committee assigning problems to people,” he said.

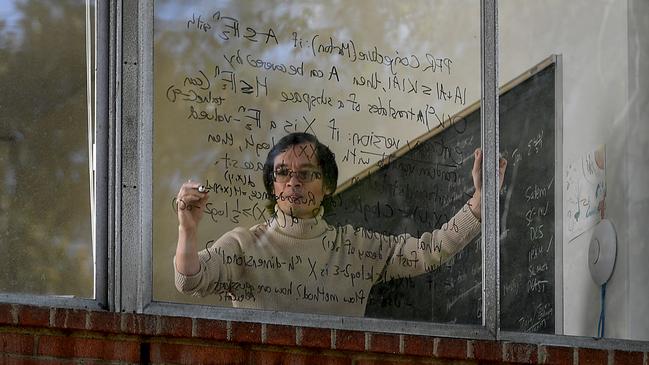

The word mathematician often conjures images of a greying old man dressed in tweed in front of an oversized chalkboard.

But Dr Tao looks every bit the Aussie turned Californian, donning a pair of Birkenstock sandals and a turtleneck sweater with the sleeves rolled up in his office which is laden with haphazardly placed mathematical books, including some of the dozen he has authored.

Maths has long been a misunderstood and solitary field, but Dr Tao is working on changing that.

“Mathematics is still stuck in the 19th century,” he says.

“Increasingly I’m interested in all these new technologies like AI, but also ways to bring together crowds of people through the internet to work on math problems, how to change the way we do mathematics.”

Due to the precision required, it has traditionally been difficult for mathematics to emulate the success of other fields that can enlist the help of citizen scientists - for example, amateur astronomers discovering comets or amateur biologists collecting butterfly species.

But advances in technology are opening the door to collaboration.

“I’m running a project right now proving some new theorems with 50 other people, usually we only collaborate with four or five other scientists,” Dr Tao said.

Dr Tao was a member of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology under the Biden administration in which he advocated for scientists to help create a responsible culture around artificial intelligence technology.

AI has been described as the downfall of many professions, including mathematics, but Dr Tao is confident that he and his blackboards aren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

“It (AI) is still just like working with a really enthusiastic, but incompetent intern, very eager to try stuff but always making so many mistakes, and you have to clean up after, after the mess,” he said.

“But that’s just how it is today, it’s getting better at the moment and at some point, it will cross over and it will be easier when I do calculations to just start by talking to an AI.”

And while his academic achievements are unparalleled, Dr Tao insists he has plenty of skill deficits.

“I’m pretty sure you don’t want to hear my singing,” he says.

“My handwriting, anything that involves arts and crafts, I’m no good at.”

In July, Dr Tao will celebrate his 50th birthday and he acknowledges the cognitive decline that accompanies ageing.

“Yeah I certainly feel slower than I did in the past, but I also know a lot more,” he says when asked about the inevitable change.

As a student, he was in awe of his adviser who would use his decades of experience to help solve equations, citing other work that in minutes could help answer a problem he had been grappling with for days.

“Nowadays, I can pull the same trick,” he says smiling.

“The analogy I like to give is that doing mathematics is kind of like jumping into a TV series that’s been going on for a couple thousand years, and at first you don’t know the characters or the plot or the backstory and you have to do all this reading and research.

“But once you’re old and jaded, and you’ve seen a lot of these TV shows, you can actually just pick up just the plot without knowing the details.”

Dr Tao doesn’t have much time for watching non-maths television these days - he admits he’ll skim the synopsis on Wikipedia to keep up to date with the movies everyone is talking about.

“One by one, my hobbies have kind of been squeezed out by time constraints,” he says.

“I used to like watching anime and playing badminton, I still ride my bike,” he says, gesturing to the bicycle propped against the wall of his office.

Opening his calendar to find an appointment time for a student who knocks on his office door, the screen fills with a colourful Tetris of meetings, classes and responsibilities.

This interview remained a tentative diary entry until hours before due to another prior engagement in Dr Tao’s schedule - jury duty.

Even the world’s greatest minds must answer the call of Lady Justice.

In a stroke of luck for this magazine, and quite possibly a guilty defendant hoping to outsmart a bona fide genius juror, Dr Tao was not required to serve.

More Coverage

Originally published as From Sesame Street to the Mozart of maths: Meet Aussie genius Terence Tao