Australia’s cost of living triggered by entertainment, health costs

The rising cost of food seems to go hand-in-hand with talks of inflation, but new figures tell a different story.

SPECIAL INVESTIGATION

Australians are spending less of their income on food than five decades ago, new data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics confirms — despite basic groceries receiving blame for the rising cost of living.

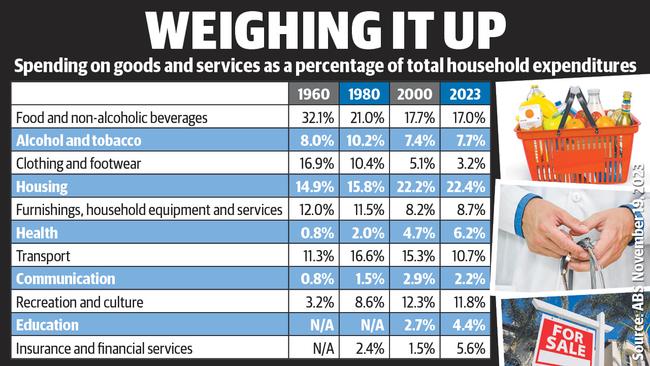

An analysis of ABS numbers by The Weekly Times shows spending on food dropped from 32 per cent of household expenditure in 1960 to 21 per cent by 1980, to finally settle at just 17 per cent today — mainly due to agricultural advancements.

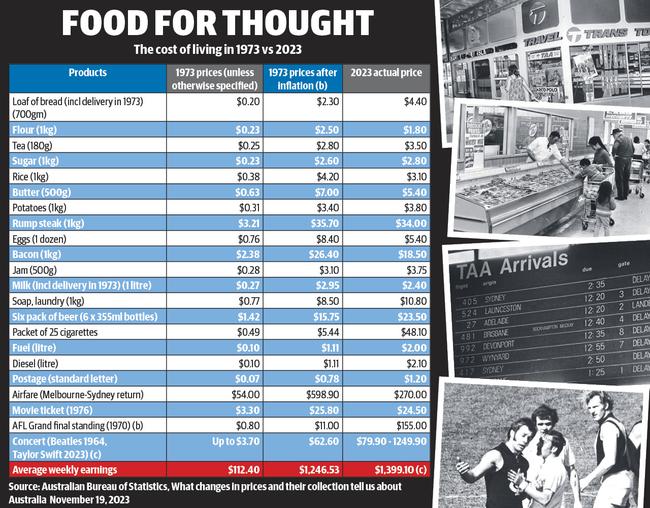

The analysis shows the inflation-adjusted cost of supermarket staples — flour, rice, milk, butter, bacon and eggs — are far below what households paid 50 years ago.

In 1973 consumers paid 76 cents for a dozen eggs, which after inflation should cost $8.40 today, but are plucked off the shelf for just $5.40.

A 500g block of butter that sold for 63c in 1973 should cost $7 today in real terms, but sells for $5.40. Flour is 28 per cent cheaper, rice is down 26 per cent and the cost of bacon sliced back by 30 per cent.

A litre of milk that sold for 27 cents a litre in 1973, including delivery, which the ABS says should cost almost $3 a litre today due to inflation.

But supermarkets have cranked their house brand prices back to $1.60 a litre, while proprietary brands sell for $2.40 a litre.

Dairy Farmers Victoria president Mark Billing said: “People seem to be more than happy to spend a lot on a mobile phone, while haggling about paying an extra 10 cents a litre for milk”.

He said was easy for politicians to “belt away” at supermarkets over food pricing.

“But if supermarkets get pressured it will put pressure ‘down’ on us,” Mr Billing said.

Last week, a Senate select committee was formed to “inquire into and report on the price setting practices and market power of major supermarkets”, after Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced yet another inquiry into competition.

Both sides of the political divide have blamed food costs in recent months as a factor behind the cost of living crunch, including Opposition leader Peter Dutton and federal Agriculture Minister Murray Watt.

Last week, Senator Watt called on supermarkets to freeze the cost of a Christmas ham, declaring he was “putting the big retailers on notice ahead of the festive season” over rising food costs.

But pork prices have steadily declined in real terms, due to pork producers lifting feed efficiencies, more effective climate control and higher sow pregnancy rates.

The ABS reported the inflation-adjusted cost of a kilogram of bacon that cost $2.38 in 1973 should now be sitting at $26.40, but is selling instead for $18.50 on supermarket shelves.

Victorian Farmers Federation pig group president David Wright said food was not expensive and that pork was “well priced” for a product that was the second-most eaten meat after chicken.

“We’re doing our best to keep costs as low as we can as all of us are feeling the pressure from the supermarket to our farm gate, every time a feed truck backs up to a silo,” Mr Wright said.

Consumers are feeling the effects of a surge in food prices following the lifting of Covid restrictions and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as supply chains tightened.

But as of last month the ABS data shows spending on food sits at 17 per cent of total household expenditure compared to 17.7 per cent in 2000.

The data also shows the biggest cost-of-living driver is not food, but housing, health, communication and recreational spending.

Footy fans who paid 80 cents for a standing-room ticket to watch Richmond beat Carlton in the 1973 VFL grand final, should only be paying $11 today, not the $155 charged by the AFL.

The other big cost-of-living drivers are housing, which has gone from 14.9 of total expenditure in 1960 to 22.4 per cent today and health care — which has risen from 0.8 per cent to 6.2 per cent of spending over the same six-decade period.

Monash Business School applied macroeconomist Mark Crosby said the rising cost of servicing a mortgage had altered the spending habits of many Australians in the past 12 to 18 months.

Professor Crosby said it was unsurprising that basic food costs had altered little in the past five decades, with housing, health and education exacerbating the cost-of-living crunch.

“About one in 50 borrowers nationally are experiencing financial stress at the moment but next year, as many come off their fixed rate to variable, that figure will rise to about three in 50 borrowers,” he said.

“Rising housing costs have had a marked impact on consumer sentiment and that’s led in many cases to altered spending on things like gym memberships, streaming subscriptions, memberships and incidental entertainment more broadly.

“It’s unsurprising the price of many basic food items have either remained roughly in line with inflation or decreased as a result of technology-driven efficiencies.”

Werribee egg producer Brian Ahmed said “eggs got cheaper because we used technology to improve our efficiency”, from temperature-controlled sheds to labour saving automated egg collection.

“With a 30,000 bird shed I can collect those eggs with the flick of a switch, not touching an egg from chicken to pack,” he said.

Mr Ahmed said it was the same story with dairying and pig industries, where scale, technology and breeding have delivered major gains for consumers.

Of the 12 food items monitored by the ABS, 11 either stayed close to the 1973 price or reduced significantly.

The exception was bread which should cost roughly $2.30 based on 1973 prices but the ABS calculates its average around $4.40 per loaf in 2023- despite the cost of flour having dropped over the past five decades.