Google AI to help fight the fight for kelp on Great Southern Reef

New maps have revealed data about Australia’s oceans and what’s threatening the seafood we enjoy. Tasmanian scientists fighting to save it are getting help from an unexpected source.

Let’s face it: kelp ain’t super cute. Drab olive in colour, slimy to touch, with a weird configuration of manky leaves, berry-shaped bladders and long creeper parts, it’s like the marine version of the camel, the creature designed by committee.

To the untrained eye, it can look like so much straggly brown muck, clogging up otherwise pristine waters as it bobs about.

But kelp is amazing. Giant species of the seaweed can grow as much as 50cm in a single day, and reach lengths of up to 60m, providing shelter and food for an abundance of marine life at various depths.

One giant kelp forest near the Actaeon Islands, off Tasmania’s rugged south coast, is such a beast that during its peak spring growth season, its mass grows by an extra two tonnes every day.

But that beast is becoming exceptional in another way: rarity.

It’s been estimated that 95 per cent of Tasmania’s giant kelp forests have already died off, and the range of the golden kelp fringing southern Australia has diminished by 100,000 hectares in just the past 15 years.

These are alarming statistics, but scientists fear what they could be prefacing: wider ecosystem collapse. Bye bye marine life; bye bye fishing industry.

You can blame climate change for this: marine ecosystems around the world have recently been experiencing unprecedented levels of warming.

Changes to the East Australian Current are also a factor. Remember the slipstream that Nemo, Dory and the cruising turtles used to get to Sydney in the movie Finding Nemo? It’s now faster and more powerful than it used to be, pushing warm tropical waters further south. Tassie’s typically chilly 14-15C waters are being warmed to 20C – not bad for a refreshing dip on a summer’s day, but deadly for giant kelp.

Fortunately, these amazing ecosystems have some passionate advocates in their corner, fighting for their survival. Yes, kelp is getting help.

Dr Scott Bennett from the Great Southern Reef Foundation knows what he is up against, fighting the fight for kelp when there is so much attention paid to the myriad threats facing the Great Barrier Reef.

With its vivid corals and gaudy marine life, Queensland’s No.1 natural attraction hoovers up the visitors, the research funding and the conservation efforts.

By comparison, the Great Southern Reef, where the kelp forests are, is vast, diffuse and relatively unknown.

Sitting in generally cooler, less snorkel-friendly waters that stretch across Australia’s southern coast and halfway up its flanks, it consists of many different parts, and was only named in 2015. It gets less than 1 per cent of the funding that goes to the Great Barrier Reef, Dr Bennett states.

And yet it’s an even bigger biodiversity hotspot, with 70 per cent of its species found nowhere else on Earth.

“If we lose the kelp forests, we lose those species,” Dr Bennett says.

He’s talking about such evolutionary wonders as the leafy sea dragon, an animal so perfectly blended with its environment that it looks and moves like a piece of kelp itself. But he’s also talking about the things we love to eat.

“Our largest wild fisheries are for rock lobster, and fourth largest is abalone; both these things are only found in kelp forests,” Dr Bennett says. “When we lose these habitats, we lose these fisheries.”

Scientists say the first kelp forest deathsstarted to become noticeable in the 1980s, but there is some evidence to suggest the species has been in decline for much longer.

“Research is being done on admiralty charts from the mid-to-late 1800s showing there was potentially even more kelp then,” marine ecologist Paul Tompkins says.

“There are also descriptions from captains (of that era) – they couldn’t get their boats into certain areas because the kelp was so thick and so dense.”

Mr Tompkins works for the Australian Nature Conservancy, one of the groups spearheading giant kelp restoration efforts, which has 16 trial sites in the waters off Tasmania right now.

“We’re monitoring survivorship and growth – the idea being we’ll choose three or four best performing of these sites for larger-scale work this year, going hectare scale,” he says.

The key to successful restorationis workingwith the hardier sorts of giant kelp, the alpha types with the genetic makeup that make them resilient to marine heatwaves.

A team led by Dr Anusuya (Sui) Willis at the CSIRO in Hobart has been analysing the DNA of giant kelp in an attempt to isolate those precious genes, and breeding the “superkelps” of tomorrow. It’s a multistage process, starting with collecting spores from the kelp blades, which then form microscopic organisms called gametophytes.

“We can store the gametophytes in stasis for more than 30 years for genetic conservation, and also as a seed bank to grow new kelp for the restoration efforts,” Dr Willis says.

The scientists kickstart the next stage of the kelp’s reproduction cycle simply by moving their samples from red light to blue.

When exposed to the new lighting conditions the gametophytes suddenly start getting frisky, bringing to mind some alarming comparisons to teens and blue light discos.

The baby kelp are later sprayed on to twine and deposited in hatcheries, where they grow at phenomenal rates. With the right nutrients, individuals will grow from about one millimetre to 10 metres in a single year.

The genetic research and the restoration programs are painstaking work – but the efforts have recently received a big boost thanks to Google.

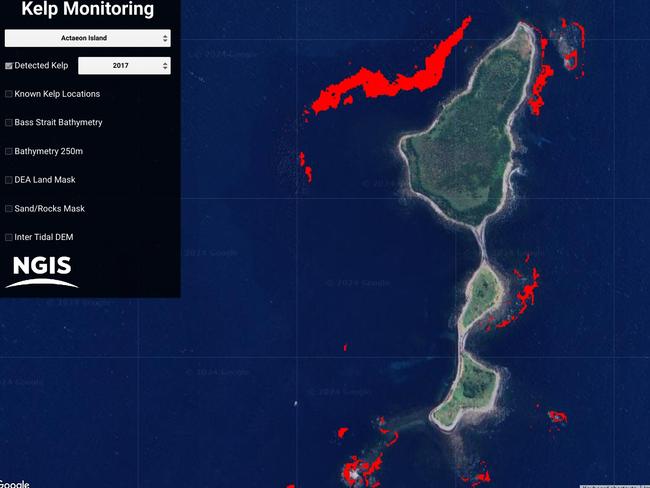

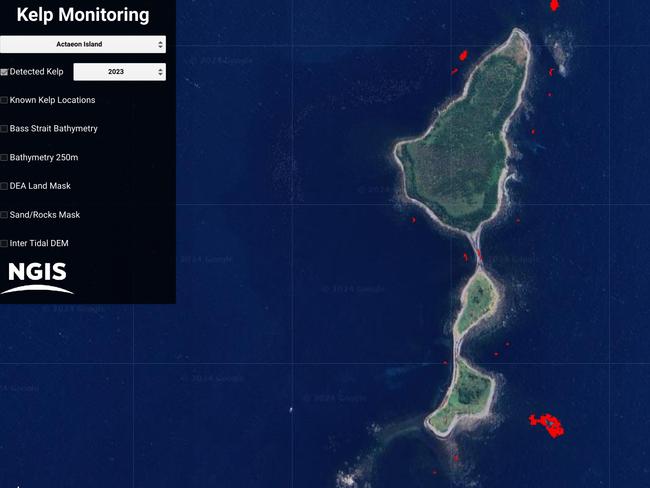

The tech giant has made two of its artificial intelligence tools, DeepConsensus and DeepVariant, available to researchers to enable them to speed up their analysis of kelp DNA, while Google Earth Engine and its cloud-based artificial intelligence platform Vertex AI are being used to map the remaining giant kelp forests. The scientists say Google’s assistance in both areas could be game changing.

While the maps have yet to be verified by fieldwork, they appear to show what the kelp campaigners have been warning about for years: decimation on a massive scale.

But getting attention and support for the kelp fight remains a challenge.

Campaigner Dr Aaron Eger has a ready list of reasons why we should care more about kelp forests. He cites their prevalence (fringing one-third of the world’s coastlines); their nurturing of marine life; their role in helping remove carbon from the atmosphere, and nitrogen and pollution from the water; and their estimated economic value ($110,000 per hectare).

“Kelp are really the habitat that’s holding our oceans together across most of the world’s coastlines,” he says.

But he cheerfully admits he was drawn to kelp because it’s like the road less travelled; growing up on Canada’s “very dark and cold” west coast may have had something to do with it, he says.

While some are easily entranced by the pretty colours and easy accessibility of coral reefs, for Dr Eger and others like him, the challenge of kelp (colder waters, less obviously “charismatic”) makes it a more rewarding study.

More people are waking up to the wonders of kelp, he says.

“Look at My Octopus Teacher, the best documentary picture for 2021. It was largely filmed in a kelp forest,” he says. “People are becoming more familiar with it, but there’s still a long way to go.

“It’s forgotten and largely underfunded, but we’re trying ways to change this.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Google AI to help fight the fight for kelp on Great Southern Reef