Chaos, trauma, smuggled booze: Melbourne Herald reporter Alistair Smith recalls Cyclone Tracy

On Christmas morning, 1974, Melbourne Herald report Alistair Smith was dispatched to cover Cyclone Tracy. Smith provided his first-hand recollections to this masthead to mark the cyclone’s 50th anniversary.

On Christmas morning, 1974, Melbourne Herald report Alistair Smith, who had been recruited from Scotland in 1966, was dispatched to cover Cyclone Tracy, alongside the Herald’s man in Darwin, Kim Lockwood. Smith has provided his first-hand recollections to this masthead ahead of the cyclone’s 50th anniversary.

Like most of Australia, I woke to perfectly normal Christmas morning in 1974. My wife Nancy and I opened Santa presents with our daughters, dressed them in their finest, packed the car and drove to the home of friends for Christmas lunch. Our hostess broke the news, emerging from the kitchen where she was listening to the radio while checking the turkey. “Darwin has been hit by a big cyclone,” she told us.

It soon became obvious that Cyclone Tracy was not your regular storm, but had left a trail of death and destruction on a scale never before seen in Australia.

Like newsrooms everywhere, The Melbourne Herald was working on a skeleton staff. Married reporters (almost entirely men) with children, the bulk of the experienced staff, had been given leave over Christmas. Many of them were out of town with their families. I rang the office and basically said, “I’m around, if you need me.”

Shortly afterwards, I took a call, “Can you come in. We need someone to work out how we can get a team into Darwin.” Our host agreed to run Nancy and the kids home after lunch while I drove my car into the city to the Herald and Weekly Times head office in Flinders St, grabbed my contact book from my desk and started working the phones, but there was no way I could find a flight or any other form of transport to get into Darwin, as the airport was only open for limited military emergency flights, and all roads were blocked.

An airline contact suggested our best plan might be to have our team on standby at the airport, ready to move at a moment’s notice. I was designated myself, and sent to the airport with photographer Bruce Howard and a portable wire photo transmission machine. A car was dispatched to my home to pick up some clothes and toiletries. Another wait began, and I prowled the airport between the desks of the then domestic carriers TAA and Ansett, with an occasional detour to Qantas in case the national carrier was press-ganged into service.

“I can get us as far as Alice Springs,” I reported. “But no further. We could be stuck there.”

“Take it,” I was told. “At least it’s closer.”

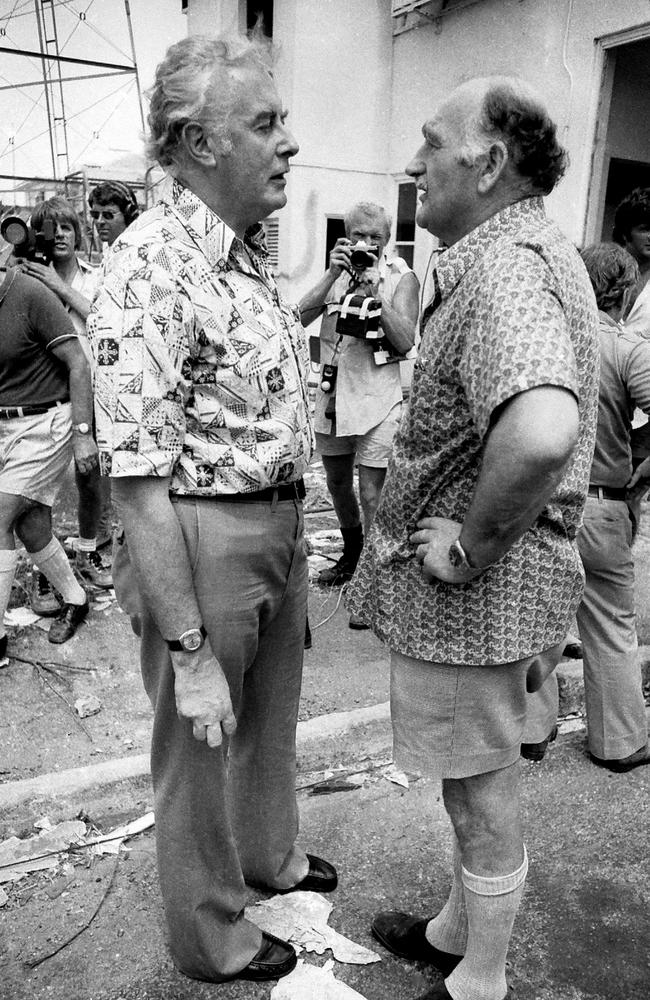

I got our tickets, turned from the counter and almost bumped into Jim Cairns, the acting Prime Minister (PM Gough Whitlam was overseas on holiday), his wife Gwen and a small entourage. I’d come to know Cairns over the years, through reporting on his many anti Vietnam War activities, and we were on first name terms. Alongside him was the Leader of the Opposition, Billy Snedden, with a shiny pair of galoshes tucked under his arm.

I’d heard on the grapevine that they were on their way to Darwin, travelling on a plane carrying medical personnel and relief supplies. Inquiries about that had led nowhere.

“Hi Jim,” I said. “Any chance of a lift?”

“Sorry, Al. No room.”

A few hours later, Bruce and I deplaned at Alice Springs, prepared to set up camp in the tiny lounge and start working the system once more. As we crossed the tarmac, we met Cairns again, striding in the opposite direction. His original plane had stopped to top up on fuel to be certain there was enough to get out of Darwin again, and then a decision was made to change planes completely, hence the delay that had enabled us to catch up.

“So, any chance of that lift now?” I asked.

“Okay then. Just follow me.” And we scurried after him while he organised for us to be squeezed on to the back of the plane. I’m sure there were no rules about actually having a seat or a seat belt at this point. As we started to taxi, Bruce pointed out the window. His wire machine was sitting, almost forlornly, on the tarmac. He now had no way of getting pictures out.

I remember our descent into Darwin clearly. The runway, shared by civilian and RAAF planes, had been cleared enough to allow a few flights in, debris simply pushed aside be bulldozers. Our pilot descended through a series of figure-of-eights, banking the plane to observe the runaway for himself. What we saw as his did was total devastation. There seemed to be no building left intact. It was like the images of the aftermath of the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was impossible to comprehend. There seemed to be nothing of Darwin, a city of 45,000, left.

Major General Alan Stretton, head of the National Disasters Organisation, appointed by Cairns as the supreme commander in charge of relief operations, had flown in on a military aircraft the night before, landing by the lights of trucks and kerosene flares. He was there to greet Cairns and the relief team. We were all in a state of shock. There was a convoy of vehicles, so we cadged a lift to town and made our way to the Herald company house, to meet up with the Herald’s permanent Darwin correspondent, Kim Lockwood. The Herald had maintained a presence in the Top End for many years, firstly with Doug Lockwood, Kim’s father, and now with Kim. The house was office and home.

It was of a tropical northern design and was still standing, although badly wrecked by the cyclone. Most of the walls were of louvred glass which could be opened up to allow some sort of cooling breeze to flow through. Cyclone Tracy had blown out the glass, but the force of the wind then howled through the house without meeting anything solid to push over. There was glass and debris everywhere, and much of it was soaking wet, but there was still a roof over our heads. It was to become our headquarters and sleeping quarters, bunking down wherever we could.

I’m fairly sure Kim was traumatised having gone through the entire cyclone experience himself. He had been unable to contact Melbourne because all communications, including the Army and the RAAF, were out of action. The local telephone exchange was all but destroyed and telex machines sat in inches of water. But the story could not have been told without Kim’s incredible local knowledge and range of contacts which were to get us into places and talking to people that other organisations could not.

The first job was to dig his car out from under the rubble of the garage. It was windowless, but it worked. And it had fuel, for this was a town without anything: no power, no water, no fuel, no phones, no accommodation, no medical supplies, and no food, for without refrigeration everything was rotting quickly. That was why Stretton decided to evacuate everyone except those capable to helping clean up and rebuild. The fewer people, the fewer logistic problems. We opened a few tins at random, tipped them into a wok and lit a fire under it using broken up picture frames, the right size for kindling, and washed it down with warm beer. After that, like everyone else, we were relying on Red Cross hand-outs.

The following days remain a blur, as we chased stories. There was no shortage of them, but the problem was getting them out. Bruce Howard would hand a paper bag of exposed film to the pilot of a plane carrying evacuees and ask him to put it in a cab to the newspaper office of whatever city they were flying into. Kim managed to get access to one of the flooded telexes, which I had never used before. I can’t even remember most of the stories I filed, but I do remember a piece I wrote about sitting around in a darkened basement bar (no drink, because Stretton had banned it) as locals exchanged stories of their experiences … in many ways, they were all the same. I’d filed by phone, because Stretton had realised the importance of getting the message of the dire situation out and organised media access through the telephone exchange. I had a terse exchange with a news editor who was insisting that we needed full names, ages and addresses, as per the company style book. “That’s the whole effen point!” I yelled. “There are no addresses. There are no effen houses, and everybody is in the same effen boat whatever their name or how old they are!” I slammed down the phone and never had any point of any story ever questioned by him again.

At one point, Stratton turned to the reporters on the spot, “the press corps,” as he referred to us, for help in containing some of the outrageous stories that were being printed down south by the more sensational papers, who were latching on to any rumour or bit of gossip gleaned from survivors who’d made it south. He simply asked if our editors could check these stories back through us before publishing them … bulldozers digging mass graves, hundreds of people missing or dead that the authorities weren’t admitting, Aboriginal people being driven out of town and dumped in the desert, widespread looting at gunpoint, the spread of typhoid, cholera and other exotic diseases. Sure, there were people still unaccounted for, mainly itinerant crew members of fishing trawlers who were at sea when the storm hit, but their numbers were small.

And there was some talk by rednecks in town that Aboriginal people should be moved out “because they spread disease.” Stretton quickly quashed that idea. Everyone was to be treated the same. He also had to make that point with the RAAF who had been prioritising the evacuation of their own personnel rather than following protocol. He also constantly battled the Army chiefs who thought they should be running the show.

Stretton deals with these in his book, ‘The Furious Days’, and praises the work we did.

Apart from access to communications, “the press corps” had no privileges, but, hey, it was coming up to New Year, the town was dry, and journos are renowned hard drinkers, aren’t they? Thus it came to pass that a couple of inbound flights arrived carrying crates clearly marked, “Unexposed film, do not open.” These were stored in a bath at the TraveLodge Hotel, where some rooms had windows and there was some sort of order, and where Mal Walden and the Channel 7 crew had set up their camp. Ron Connelly, of 3DB, wasn’t known as “Ron the Con” for nothing, and managed on some pretext to gather a collection of chits from the Red Cross for ice.

It was party time, and we started celebrating New Year in order of the time zones of those present, beginning with New Zealand, moving to the Eastern States and making allowance for daylight savings differences. There was a pause at midnight local time. Somewhere out in the darkness a bugler started playing the Last Post. There was absolute silence. It was an incredibly haunting and sombre experience. We did resume our partying, a case of releasing the steam valve rather than celebration. My final recollection of the night was when a guy called Tom Kent, reporting for Associated Press, announced in a loud voice, “In 15 hours, it will be New Year in Cleveland, Ohio!” before collapsing unconscious on the floor. I’ve often wondered what happened to Tom after that.

By now, things were well organised and under control. Stretton realised that the sooner he handed powers back to the regular authorities the better, and his departure was swift.

Most of that first contingent of reporters, including myself, were on our way home, too. I’m not sure what day it was, although I have a note from the editor-in-chief dated January 3, that I was getting a bonus. We flew out on a giant U.S. Air Force Starlifter, a handful of us huddled in its cavernous body strapped in against the fuselage on webbing seats like something out of a war movie. As we approached the air base at Ipswich, a big Master Sergeant (also straight out of a movie) kept popping down from the flight deck above us and peering out the windows. “The instruments are telling us an engine is on fire, but I can’t see anything,” he said calmly, supposedly to reassure us.

But we did do the full emergency landing, descending very quickly, then screeching to a halt in the middle of the runaway as emergency vehicles, lights flashing, circled us. We didn’t do the emergency slide, but we made it to the tarmac very quickly. No one could see any fire, and a Jeep drove us to the terminal and to get a ride into Brisbane, where we stayed overnight at a five-star hotel. We must have bought new clothes, because I can remember a slap-up meal in the five-star restaurant. We’d lived in a couple of shirts and Red Cross handouts for 10 days.

On top of the bonus (it was huge, $2000 at the time, worth $12,500 in 2024), I was ordered to take two weeks off, despite my protestations that I was fine. I was exhausted, true, but someone back then must have heard about PTSD. Nancy [my wife] and I took some time to ourselves (yes, our Christmas hosts looked after the kids) at a resort at Marysville (ironically, a town that was to be completely destroyed in the Black Saturday bushfires of 2020).

We went to the movies and there was a newsreel about Cyclone Tracy. I remember an aerial helicopter shot taken as it flew over street after street of destroyed homes looking for survivors, and I simply collapsed in tears.

Remember, I was only there as an observer and I didn’t go through the storm, or suffer any loss. But it brought home to me Stretton’s words, “The damage to the minds of the survivors can never be calculated.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Chaos, trauma, smuggled booze: Melbourne Herald reporter Alistair Smith recalls Cyclone Tracy