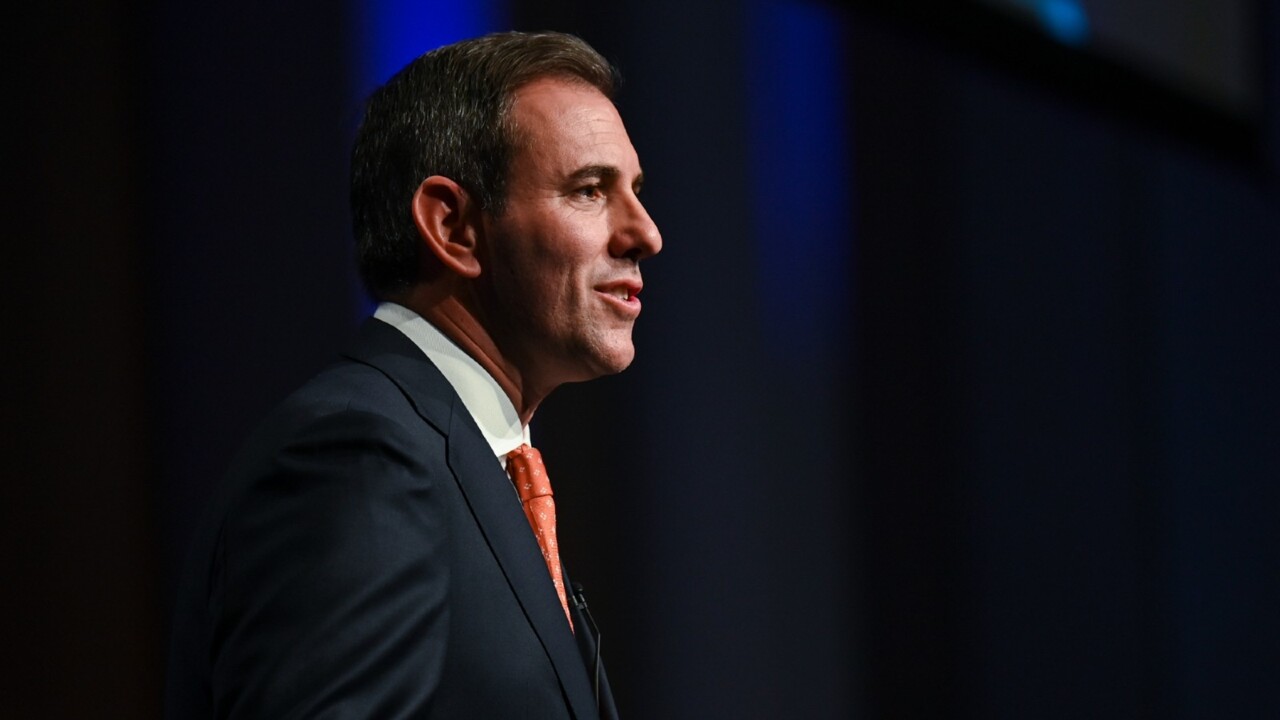

Albanese government anniversary: Ag Minister Murray Watt reflects

With a year on the clock, the Albanese government is no longer shiny and new. We chat to Agriculture Minister Murray Watt on the highlights and lowlights from the past 12 months.

A month after being sworn in as the nation’s 35th federal agriculture minister, Murray Watt was facing “a very early test of me and the government” in deciding how to keep Australia foot-and-mouth free after the deadly disease had spread to Indonesia.

There are few more dire prospects for the nation’s $90 billion agriculture industry with any border incursion capable of crippling the livestock sector and destroying farm businesses, food insecurity and trade.

But before rolling up the sleeves the Queensland senator had to be briefed on the intricacies of a biosecurity risk he knew little about.

“That was a baptism of fire to go through foot and mouth so early while also dealing with floods in a lot of the country at the very same time,” Senator Watt, who is also emergency management minister, said.

The FMD threat remains on the nation’s doorstep, but the shield has so far held, and Watt believes the episode signalled to industry that he would readily listen to experts and “act really decisively”.

“I don’t pretend to know everything or have all the answers, people can pick a phony,” he said.

“So, from day one I was determined to just be straight with people. And I think they decided to give me a go after that.”

In a twist, the farming lobby had expected to be dealing with now Housing Minister Julie Collins, Labor’s then shadow agriculture minister, after the party’s narrow election victory on May 21, 2022.

The post-election Cabinet musical chairs likely why Watt — around floods and pestilence — had to “quickly” develop his priorities and “after listening to farmers and farm advocates” settled on input costs, biosecurity, workforce shortages, trade, and climate.

A hallmark of the Albanese government is that ministers are pretty much left alone to run their portfolios, while stakeholders say that communication with a Labor party who has “tried very hard” to be collaborative has generally been easier than with its predecessor – despite sometimes differences of opinion.

A prime example is Watt, a dairy farmer’s son, raised in Brisbane and a former practising lawyer, facilitating a rare agreement between farmers, unions, and employer groups to tackle dodgy labour hire operators.

“I feel like I have been consistent in sticking to those priorities and I hope people feel that I have done a good job,” he said in a candid interview with The Weekly Times.

“I think there is a good relationship of trust between me and the key advocates in the sector. I guess that it is interesting because it has not always been that way with Labor government agriculture ministers.”

Watt’s job has admittedly been made harder by Chinese trade bans and global economic storms, while geopolitical strife and pandemic issues have largely tied his hands against supply chain disruptions and soaring input costs.

The 47th parliament keeping its radar firmly focused on inflationary pressures, energy, and social policy also sometimes runs contrary to his own agenda.

And, in the spirit of departing government’s leaving timebombs for their replacements, finding the department of agriculture was operating deep in the red was all-time.

Speaking on his year in office, Mr Watt said securing $1 billion in the 2023-24 federal budget to deliver a sustainable funding model for biosecurity for the first time was a marquee achievement.

He also cited increasing Pacific Australia Labour Mobility workers as a win in a tight labour market but, even then, a shift in tone of Australia’s foreign policy and regional engagement has dried up agriculture’s traditional worker pools and left him with few, if any, other options.

Farm leaders also reiterated demands for a dedicated agricultural visa this month, angry at a failure so far to generate a substantive plan to increase regional workers, saying the PALM scheme as it stands will not deliver at a pace or the skilled or long-term numbers needed.

But while stakeholders say Watt’s assessment of working relationships are real, the courtship has not been without quarrels.

For one, many are opposed to a new biosecurity protection levy forcing producers to help pay for that long-awaited sustainable model.

He is also leading a Labor charge to stop the live sheep export trade that continues to deeply burn pockets of the industry, while its focus on animal welfare standards is perceived by some farmers as a personal attack.

Although Watt says this is more about correcting international misconceptions regarding Australian farming standards.

Meanwhile, a $302 million Climate Smart budget package has signalled an increasing focus in coming months on helping farmers overcome climate challenges and, again, helping demonstrate the industry’s climate stripes for overseas markets.

Watt says he also constantly prosecutes the case for increased funding for agriculture in Cabinet and with individual ministers, but the work of other ministries can also make things more difficult.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek’s shock plan to buy back 49 gigalitres of water to hit a Murray-Darling Basin Plan target is causing unease. As is Infrastructure Minister Catherine King’s review of the nation’s 10-year infrastructure pipeline placing hundreds of regional projects in jeopardy – while farmers drive on dangerous country roads.

In recent days, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has revealed that he hopes his government will last several years beyond the current term.

And, while that is hardly a revelation, it does suggest agriculture’s need to have its problems fixed now may not be matched by the government agenda.

An assessment of its performance so far likely hinges on the the colour of the corflute.