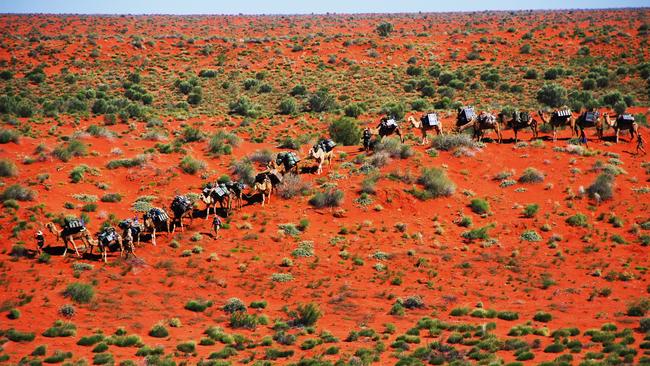

Andrew Harper’s Australian Desert Expeditions camel treks for science

Travelling into the Australian desert is soul-enriching for cameleer Andrew Harper, but it also has its serious, scientific side, writes SARAH HUDSON

WHEN Andrew Harper looks across his 20ha bush block in Deniliquin, in the NSW Riverina, he’s most likely thinking of the Australian desert.

Even when the former jackaroo — who has worked on some of the Riverina’s largest Merino stations — drives past the area’s sheep mobs, his heart is with his 16 camels.

That’s what happens to a person after they’ve spent each winter for more than two decades trekking with camels in the nation’s most remote desert regions.

“After all these years, I think when I come home more of me is sitting on a plateau above the Simpson Desert, looking down on the rest of Australia,” Andrew says.

“When you walk around the desert with camels as long as I’ve been doing, it can be an incredibly rude, abrupt and brutal shock to come back to the humbug of the world.”

The 54-year-old has dedicated his life to the 45 per cent of the continent yet to be comprehensively surveyed by scientists, even awarded an OAM for service to environmental science, research and adventure tourism for his work.

It was in 1995 that Andrew first spent two months working in the Simpson Desert for a camel trekker.

For the next four years he undertook something akin to an apprenticeship, embarking in 1999 on his first Tropic of Capricorn trek, walking for seven months with three camels across 4637km, from the Pilbara to central Queensland, raising funds for the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

(In October to December, he will continue that Tropic of Capricorn trek, walking with no camels in Paraguay and Brazil.)

“I first had the idea of walking across Australia when I was a jackaroo in Longreach. There was a sign on a public road on the property that said ‘Tropic of Capricorn’ and I got curious about what it meant,” he recalls.

“I knew then I was going to walk across the country and do it with camels. Physically it’s not that hard. You’re not pulling a sled in the North Pole, you’re walking. It’s pretty straight forward.”

In 2000 Andrew bought the Outback Camel Company, and for several years ran commercial treks for travellers into the desert. He now does one what he calls a mindfulness trek each year. “I started the mindfulness treks after I realised walking in the desert with camels focuses and empties the mind. It’s completely rejuvenating, good for the soul, the spirit,” he says.

“In an urban environment people are bombarded with the humbug, the crap all the time so it’s inevitable if you remove yourself from that it’s beneficial. After taking thousands of people into the desert I see them change, relax, unwind, reconnect.

“But the slow travel, the mindfulness is a by-product.

“It’s not my main motivation.”

Andrew’s main motivation is exploring the desert for science and, as such, the Outback Camel Company morphed into his not-for-profit Australian Desert Expeditions, which he started in 2007.

Australian Desert Expeditions has a full-time chief scientist, two part-time scientists, as well as a voluntary advisory panel. It partners with universities and national research institutions to conduct scientific and ecological surveys, documenting areas of the map that are never visited by conventional means and may never have been surveyed at all.

Andrew says while the research has identified rare plants and animals, more recently their focus has turned to combining modern science with “a wealth of material from blackfella occupation”.

Each year Andrew, his 16 camels, crew and scientists travel into the desert for about 14 treks, lasting between five or 16 days and walking about 15km a day.

Members of the public can join in most of those treks and assist the ecology team with the research, paying from $6000, which includes flights, food, and camping in swags, with all funds going back into the scientific research. A maximum of 12 volunteers can accompany each expedition and must be aged 16 or older and be reasonably fit. The crew carries satellite telephones for emergency communications, as well as personal locator beacons, UHF radios and a fully equipped RFDS first aid chest. “This is fair dinkum trekking, not packing the Hilux. We’re 24 hours a day outside, like they used to do with stock camps,” Andrew says. “The expedition begins where the road stops.”

The self-made cameleer — who grew up in Deniliquin and for the best part of a decade worked as a jackaroo, overseer and musterer — says having worked with all livestock, camels are smarter than horses but “not as switched on as Kelpies”.

His camels are all formerly wild and not broken in as much as “their natural instincts are honed”.

He agrees wild mobs of camels are an unfortunate historical legacy, but should be seen as an opportunity and a resource, not as a problem.

Andrew says his work is a modern interpretation of Australia’s long history of outback camel treks, dating back to 1860 when camels were brought to Australia for the Burke and Wills expedition, which, although it ended in disaster, showed the value of camel exploration.

“All I’ve done is take the history books and reactivate them. We’re doing nothing different to what the great expeditions did 150 years ago,” Andrew says. “Pack camels are still the best way to explore Australia’s great deserts with the smallest environmental padprint possible.

“I don’t think what I do now is being adventurous. A century ago everyone rode around on a horse. It just looks unusual now because everyone else is in a car. I wouldn’t look out of place 120 years ago.”