RBA could hold interest rates higher for longer due to US President Donald Trump’s tariff policy

Australia’s central bank is likely to be nervous ahead of its next rate decision for one very good reason that’s out of its hands.

Australia’s central bank is likely to be nervous ahead of its next rate decision, as US President Donald Trump initiates his tariff policies.

Households may have to wait longer for rate cuts as a changing economy is likely to lead to an uplift in inflation, meaning interest rates could be held higher for longer.

Compare the Market economic director David Koch said Mr Trump’s tariff policy was adding uncertainty, which central banks hated.

“Virtually every day we wake up and Trump has announced new tariffs or sanctions. I think the Reserve Bank’s going to be really cautious because tariffs push prices up, and that feeds inflation,” he said.

The US President has put a 25 per cent tariff on all steel and aluminium imports into the country, including from Australia.

He has also added a 25 per cent tariff on goods coming in from Canada, while China faces a 20 per cent tariff.

More tariffs are expected to come out of what Mr Trump is calling “liberation day” on April 2 when the Department of Commerce’s report into reciprocal tariffs on US trading partners will be released.

Mr Koch said these policies could push the American economy into a recession and add pressure on other global economies.

“The cycle might be starting again. We could even see rates go up, rather than down, depending on what happens in the next 12 months,” he said.

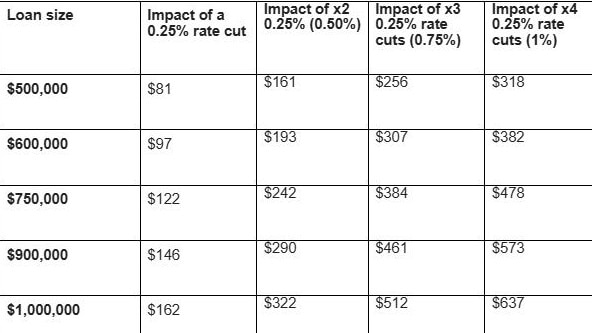

The RBA board announced a 25 basis point cut to the official cash rate on February 17-18, with their next chance to move on rates being after the March 31-April 1 board meeting.

National Australia Bank chief executive Andrew Irvine argued a similar point to Mr Koch’s during his speech at the AFR Banking Summit.

“If we do have a global tariff war, and all the drama and tit-for-tat stuff does turn into bilateral trade really reducing, and 25 per cent tariffs (are put) on a vast majority of goods and services that are highly inflationary, and if global inflation ticks up, what that means is that interest rates will not reduce to the level they otherwise would, and I think that could be problematic for Australia,” he said.

While Mr Koch said interest rates might not be cut, other economists argue a steep decline in the domestic unemployment rate should be enough for the RBA to slash rates in April.

According to Australian Bureau of Statistics figures released last week, employment fell by 53,000 in February off the back of a spike in older workers quitting the workforce and against expectations of 30,000 new jobs created.

Full-time employment fell by 35,700 in February and part-time jobs declined by 17,000.

However, a fall in jobs generally means good news for future rate cuts because inflation is lowered through reducing demand for staff, which leads to lower wages and in turn less pressure on prices.

Market Economic managing director Stephen Koukoulas said the surprising fall in the number of Australians working should be a concern for the RBA.

“Employment dropped a net 22,300 in the first two months of 2025, the weakest first two months of a calendar year since 1991,” Mr Koukoulas wrote on X.

“The RBA would be wise to cut to ensure things don’t get too much weaker. An interest-rate cut is necessary.”

Commonwealth Bank head of economics Gareth Aird said Thursday’s jobs figures “completely blindsided forecasters”, with Australia’s employment growth now looking more robust than extraordinary.

“We don’t think the RBA will be swayed by today’s labour market data at the April board meeting. That is, we still expect the board to leave the cash rate on hold and resume normalising the cash rate in May with a 25bp rate decrease,” he said.

“But at the margin it adds a little more weight to the ABS February monthly CPI indicator, due March 26.”

Originally published as RBA could hold interest rates higher for longer due to US President Donald Trump’s tariff policy