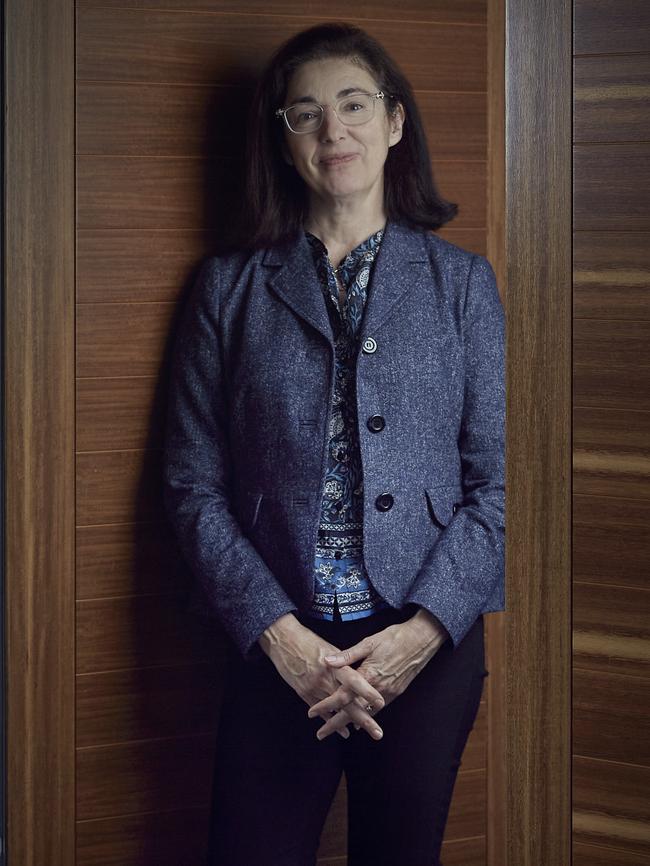

Michelle Levy reveals real price of a broken advice sector

As doubts mount over the government’s willingness to take up Michelle Levy’s financial advice reform plan, the report offers a picture of a sector paralysed by over-regulation

Lawyer Michelle Levy put a cat among the pigeons this week with an ambitious plan to blow open the moribund financial advice sector.

Her plan would make advice more accessible for the majority of Australians who can’t – or won’t – pay the sort of fees currently charged.

The blueprint for an overhauled financial advice regime carries risks, but they are risks worth taking because what we have now is a miserable mess.

It is a fading sector stacked with regulation which is being avoided by customers and professionals alike.

As Levy’s report sharply illustrates, the total number of advisers has dropped dramatically from 28,000 in 2018 to about 16,000 now.

Imagine if this occurred in any other area. What if the number of accountants fell by 40 per cent in four years?

As a result of the shrinkage, the number of Australians who receive advice has nearly halved since 2007. Meanwhile, fees have climbed close to $4000 a year. No wonder people answering formal surveys will say they ‘don‘t want financial advice’.

But this is misleading.

Anyone would welcome good advice that would improve their lifestyle; what investors are rejecting is the current advice system.

In fact, things are even worse than we thought. Levy discovered that the majority of financial advisers turned away customers in the past 12 months.

The report found 69 per cent of financial advisers declined taking on new clients last year.

In other words, even if you are willing to pay through the nose for advice, you still can’t get in the door in many cases.

We know from the recent past that just because advice is more widely available does not mean it is a better system. We might have had more than 28,000 advisers a few years ago but the “quality of advice” was much poorer.

But we cannot have a repeat of the Hayne era where advice was often a cesspit of sales culture running amok.

If the royal commission achieved one thing, it pushed the rogues and charlatans to the margins of the industry. They are still there but they are less likely to be inside the tent.

In fact, some of the worst recent scandals did not involve advisers but rather people who were pretending to be advisers.

When you boil it down, the biggest problem in financial advice today – as I’ve pointed out repeatedly – is that most Australians need occasional advice on inheritance or retirement, or digging themselves out of debt.

They are not actually running multimillion-dollar portfolios; rather, they just want a bit of advice and this is impossible under current arrangements.

What does Levy suggest?

Among the key proposals is a plan to lighten the regulations for non-relevant providers – an awkward name for anyone who might need to give limited advice but is not a formally qualified full-time financial adviser. This might be a bank clerk or a call centre operative for a big super fund.

To get such a plan off the ground, Levy believes the current best-interest duty could be replaced by a new “good advice” duty. If this were allowed it would open up the provision of advice and cut costs.

Consumer representative groups suggest this move could quickly bring us back to the rotten sector revealed by the royal commission. It is clearly the big risk as Levy believes this will not happen if it’s regulated properly.

Under this part of the plan, digital financial advice could become mainstream. This would be very welcome. We know already that routine advice should be available cheaply but regulation blocks it. Now with new artificial intelligence technology, financial advice is wide open for innovation.

Earlier this week I spoke with Ben Neilson, a financial planner and PhD who is researching artificial intelligence (AI) and financial advice.

He examined fees at four major financial advice houses for customers who were seeking superannuation contribution plans.

Neilson discovered that on average these plans took three hours and cost $900.

Neilson says the introduction of digital advice through AI software would cut the costs to $200 and reduce the time taken to half an hour. At its best, the Levy plan allows for innovation like this to take its place at the heart of they system.

For fully qualified financial advisers, Levy wants big cutbacks in red tape which invariably involves a reduction in disclosure obligations.

Specifically, she wants to get rid of the notorious “statement of advice” which every customer must get if they deal with an adviser.

This is an expensive 100-page document which considers your entire financial profile. The prevalence of SOAs is the main reason you cannot go to a planner for “a bit of advice”.

It’s time to accept that disclosure is a poor principle for financial advice regulation. Of course this sounds like an industry argument, but it happens to be true.

Nobody reads the fine print except the lawyers who draw it up.

Will the plan work? There is already talk that this report will not get through the system and it’s easy to see why.

It was commissioned by the Coalition government which favoured deregulation, but it has been submitted to the Albanese administration which is moving in the opposite direction.

It has wide support across industry and among opposition members in parliament. In fact, in a sector where they find if difficult to agree on anything – if you recall the three-year bunfight over education standards – it has on this occasion struck wide agreement.

The so-called “coalition of advice associations” representing the bulk of industry players supports the plan.

However, consumer groups have been very wary of its concepts and especially the plan to allow banks and big financial institutions back into the advice sector with lighter regulation than the current financial adviser framework.

Politically, it is highly unlikely that this overhaul will get signed off as it stands. Levy told me this week she would be very disappointed if it was not taken up in full. She also says she is puzzled by the resistance among consumer groups to give the plan a fair go.

The most likely outcome is that the government will end up cherry picking the recommendations it wants.

An educated guess here would be that the more ambitious ideas such as allowing banks back into advice do not get up.

However, entirely pragmatic ideas such as cutting out the absurd Statement of Advice rule and other outstanding examples of over-regulation may get signed off.

So far, the government has given absolutely no signal it has the stomach for major change in this area.

In fact every single utterance so far has been noncommittal. Minister Stephen Jones wants to “stress test” the report and “widely consult’ on its findings. Whatever else that means, it “means it is going to get kicked from pillar to post in the coming months.

More Coverage

Originally published as Michelle Levy reveals real price of a broken advice sector