Food waste is a $20 billion problem, or a $20 billion opportunity, depending on perspective.

FOR Rob Watkins it was, at first, a mere bump in the road. Yet, it represented one of the biggest hurdles to feeding a rapidly growing global population.

When Queensland banana grower Rob ran over a pile of green bananas on his farm a few years back, he thought little of it. They were, after all, just waste, rejected by supermarkets and consumers.

But the puff of white dust that shot from the bananas when his wheel squashed them gave Rob and his wife, Krista, an idea.

That idea put the Watkins on a path to help solve what is now one of agriculture’s biggest challenges — rivalling perhaps even climate change — the dilemma of food waste.

Food waste is a $20 billion problem, but it is also a $20 billion opportunity.

Australia wastes 7.3 million tonnes of food each year, costing the economy $20 billion.

Globally, a staggering 1.3 billion tonnes is wasted annually, at a cost of $US1 trillion.

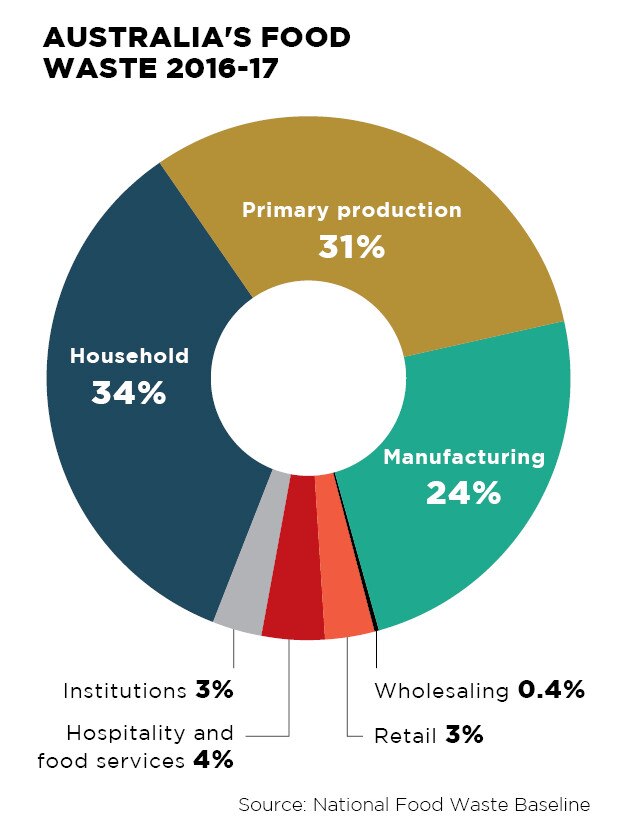

Household food sent to landfill and harvest-ready produce that remains unharvested or is ploughed back into the ground are the biggest waste culprits, accounting for 34 per cent and 31 per cent respectively, according to the Australian Government’s National Food Waste Baseline project.

A further 24 per cent is wasted in food manufacturing.

Imagine the land, water, energy and fuel used in producing, manufacturing, packaging, distributing and preparing that food, only for it to never be eaten.

Once it hits landfill, global food waste pumps 7.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year, contributing to the greenhouse effect. Not to mention the odour, leaching, vermin attraction and potential source of disease.

Fight Food Waste Co-operative Research Centre chief executive Dr Steven Lapidge says food waste is emerging as one of the “biggest issues of our time”.

“Food waste reduction and transformation is now seen as leading food and agriculture investment opportunity in Australia,” Lapidge says. “Food waste is a $20 billion problem in Australia, but it is also a $20 billion opportunity because 60 per cent of it is avoidable.”

Lapidge says cutting Australia’s food waste has huge benefits. It will lead to greater food security — increasingly important as the world population swells to 10 billion people by 2050 — increase its reputation as a clean, green and sustainable food producer, cut resources wasted on food that is never harvested, and cut greenhouse gases.

Annually, about two million tonnes of Australia’s agriculture product doesn’t ever leave farms, due to pests, disease, weather, drops in market prices or stringent contract specifications, such as quality or size.

What does get harvested runs the risk of being damaged or discarded during production, packing or handling. Lapidge says for farmers battling tight profit margins, food waste can be the difference between making a profit or a loss.

Of the produce that makes it all the way to households, nearly 2.5 million tonnes is thrown away, often because consumers over purchase or are confused about use-by and best-before date labelling.

But there is a glimmer of hope.

Rabobank’s annual food waste report has noted a 7 per cent reduction in Australia’s food waste, from $9.6 billion in 2017 to $8.9 billion last year.

Rabobank Australia’s Glenn Wealands says Australian households waste an average $890 of food each year. Wealands says while the tide is turning and more people are becoming aware of the issue, it has to be a collective change.

“At a household level food waste can be helped by pre-planning, working out what you actually need or if you can freeze or eat leftovers after the meal,” he says. “As our population increases we will struggle to feed additional mouths. If we don’t curb our waste, we could run out by 2050.”

“DIAMOND DUST”

That’s what Rob Watkins now calls the puff that appeared in his rear vision mirror that day in 2010.

Yet by accidentally driving over some waste green bananas, Rob has saved thousands of tonnes of bananas from going into landfill — and created a thriving business that is now a model for other ag sectors.

Not that long ago, Rob and Krista were among the largest banana growers in Australia, specialising in the Lady Finger variety. And like most farmers they were wasting up to five tonnes of bananas a week, deemed unsuitable for super-tight supermarket guidelines. They were also battling Mother Nature, with cyclones a constant visitor in the tropical north. Then came the “diamond dust” moment.

“Every week Rob would come home on a Friday night having just thrown out huge amounts of bananas he had put money and love into growing, due to them not meeting the market because of size or they looked funny,” Krista says.

The couple had previously noticed wallabies and cattle eating the wasted green bananas — they seemed to prefer them over the ripe ones. But when Rob drove over the green bananas that had been in the sun, they exploded to reveal a floury substance. They soon realised this powder was attracting the animals to the “unripe” fruit.

Rob and Krista’s research revealed this powder was, in fact, a form of flour — with “superfood” qualities no less. Green banana flour contains resistant starch, which according to CSIRO, supports good gut bacteria and has “incredible health benefits”. The flour is also naturally gluten free — suitable for coeliac Rob.

They assumed green banana flour was already available on supermarket shelves, but soon discovered they had the opportunity to be the first to commercialise the product. Rob started by using the waste bananas to produce a small batch of 6kg of banana flour a week, selling it through the family cafe. Within weeks it became so popular they were behind in filling orders.

Demand for the flour became so great, peeling the bananas became unfeasible, so Rob designed the world’s first peeling machine, increasing output to 300kg a week. Pretty soon, the side hustle became the main game, and Natural Evolution Foods was born.

In 2014 Rob and Krista built the world’s first pharmaceutical-grade banana flour factory, on their farm. The plant can convert any fruit or vegetable to powder in less than 25 minutes. The couple then secured a deal with Woolworths and started selling green banana flour through the supermarket in March last year.

Then came time to look at the wider food waste problem. Sweet potato suffers significant food waste due to oversupply and misshapen product so Rob and Krista had a ready supply of local waste product to make sweet potato flour, which they now also sell under the Natural Evolution brand. And they have expanded their product range to include skincare, pancake mixes and equine mix.

Rob and Krista no longer grow bananas — a bushfire last year wiped out their plantation. Instead, they buy from other farmers, stopping a fair chunk of the 500 tonnes of bananas that would go to waste in Queensland alone each week.

They now process 50-60 tonnes of produce a week and are in the process of building a new production facility in Far North Queensland, as well as investigating sites for southeast Queensland and Victoria. Krista says by the end of next year, when their new plant will be commissioned, they will have up to 10 times their current production capacity. In a few months they will launch a sweet potato vodka made from waste sweet potatoes in North Queensland.

“In every industry there is waste and there is risk, so it’s about mitigating that risk,” Krista says.

“Other farmers contacted us because they had waste, so we’ve now worked on sweet potatoes but there’s also scope with beans, broccoli, beetroot, mushrooms, citrus — it is a huge issue and we want to help fix it.

“To be able to feed the larger population it is not economic or environmentally friendly to create more food, we need to use what we have.”

HOW MUCH FOOD DO WE WASTE IN AUSTRALIA EACH YEAR?

$20 BILLION is lost to the economy through food waste

Up to 25 PER CENT of all vegetables produced don’t leave the farm — 31 per cent of carrots that don’t leave the farm equate to a cost of $60 million

$2.84 BILLION is the total cost of agricultural food losses to farmers

Households throw away 2.5 MILLION tonnes of edible food

Annual food waste cost households $2200 to $3800

2.2 MILLION tonnes of food waste is generated at point of primary production

Australia is the FOURTH highest food waster in the world per capita

Australia throws away 298KG per person each year

1/3 of food produced globally is wasted

ORANGE ROUGHY

A group of farmers has found a way to use carrots that are too big, too small, marked, or too wonky, saving about 275,000 tonnes of carrots from going to waste in the past four years.

Just Veg is a brand of ready-to-eat cut carrots, born from Kalfresh Vegetables — a farming, packing, processing and marketing business run by farmers. Today Kalfresh has farms in five regions stretching from northern NSW to northern Queensland.

One of the brand’s developers, Alice Gorman, says the farmers’ focus is on selling 100 per cent of the crop by finding customers and uses for everything.

Gorman, the wife of Kalfresh’s chief executive and part-owner Richard, says a lot of the carrots that now go into the Just Veg range were previously fed to cattle, which was a low-return use.

Alice joined four other women to find a use for the reject carrots, from which Just Veg was born.

“While we aren’t farmers, we all had our unique skillset and perspective. We’re all working mothers, we were the key grocery buyers in the family and we all had professions in our own right. We say Just Veg is powered by the farmers’ wives,” Gorman says.

Just Veg is now available in 750-plus Woolworths stores in Queensland, NSW, Victoria, the ACT, South Australia and the Northern Territory and since launching in mid-2015 has saved about 275,000 tonnes of carrots from going to waste.

“Waste is an ongoing challenge for farming businesses. Profitability is governed by how much of the crop is sold and for how much,” Gorman says.

“While our systems are excellent and we do our best to grow crops which consistently meet customer requirements, we’re also dealing with Mother Nature, the weather and other environmental factors.”

The group now donates to Foodbank and their wonky vegetables can be found in carrot beer, carrot bread and carrot vodka.

HOW EXTRA VIRGIN OLIVE OIL BECAME AN AUSSIE STAPLE

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Biggest investors, landholders: Who Owns Australia’s Farms 2025

Meet the families, billionaires and investors expanding their hold on Australian farms. Discover the biggest players of 2025 and where they hail from.

Farm succession: ‘The best time to start the conversation was yesterday’

Succession in family farming businesses doesn’t always have to be stressful, and these three successful farming families are case in point.