Olam’s Sunny Verghese takes swift action to make ag sustainable

Olam boss Sunny Verghese is tackling the future of agriculture head on.

SUNNY Verghese shows all the signs of being an untroubled man.

The founder and chief executive of the world’s third-largest agricultural conglomerate, Olam International, is standing in a flourishing crop of irrigated cotton at Emerald in central Queensland, casually dressed in a navy polo shirt and baseball cap and surrounded by local farmers.

The discussion is all about the severe Queensland drought. Emerald’s Fairbairn Dam is down to a critical 11 per cent (only recently on the rise again after promising summer rain), and local irrigation quotas have been axed to zero, slashing summer cotton plantings. But the crops that are being grown using precious stored water are looking good and, as local grower Hamish Millar tells Singapore-based Verghese, the price Olam is paying to buy and gin scarce high-quality local cotton is healthy at $585 a bale.

It’s a conversation the multi-millionaire businessman revels in, with super-efficient water use, agricultural sustainability and the latest irrigation technology to reduce crop water needs among his favourite topics.

But Verghese has something else on his mind, which he wants to share with Olam’s Emerald cotton growers.

He has no doubts the world is in the grip of a climate emergency and that urgent and system-changing action must be taken by all. Especially by farmers and agricultural corporations such as Olam that produce, process or sell so much of the world’s food and fibre.

“With climate change impacts happening right now, droughts will become more frequent, risks will be greater, and agriculture will be more volatile,” warns Verghese. “As a farmer and an investor we cannot expect to make profits year in and year out anymore, but instead have to find ways of coping with drought and adapting to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

“It might be through artificial intelligence, big data, genetics, adopting the latest technology or changing the varieties, location and types of crops grown.”

IN THE 30 years since it was founded by Indian-born Verghese in Nigeria as a cashew nut exporter to England, Olam has become a food and farming giant. It grows and buys crops from 4.7 million farmers in 30 countries; supplies 66 agricultural commodities, ingredients and food products worldwide; and has annual sales in excess of $A30 billion. With such extensive global interests, it’s not often Verghese, 60, visits Australia, where Olam has poured $1.4 billion into its agricultural holdings and interests in the past 13 years.

Olam is now one of the biggest corporate players in Australian agribusiness, ranking only behind Canada’s Public Sector Pension fund and Macquarie Agriculture in the size of its farming and rural processing investments.

In Australia, Olam has a 24 per cent share of the cotton market, owns nine processing gins in northern NSW and Queensland, and operates 15,000 hectares of almond orchards at Robinvale, in Victoria, and Darlington Point, NSW, producing 45 per cent of Australia’s almonds.

It has also built an almond processing plant near Mildura, invested in a cotton farming joint venture near Rolleston, Queensland, and owns extensive water rights to irrigate its crops. Besides being a farmer itself, Olam also buys, processes and exports mung beans, chickpeas, grains, wool and cotton grown by other Australian farmers for its global trading network.

It’s a presence backed by more than 300 permanent staff led by local Olam chief Bob Dall’Alba; a footprint Verghese is keen to grow since he believes Australian farmers rank among the world’s best. “We farm in 30 countries but see Australian agriculture as the most innovative in the world,” Verghese says. “Because Australian farming systems have never been propped up by agricultural subsidies, farmers here have been forced to be highly efficient, innovative and adopt world best-practices to compete on world markets.”

It’s a view of Australian farmers that Verghese formed in the mid ’80s, when, as a 25-year-old working in sales for Unilever in India, he was headhunted by a textile company in Nigeria looking to re-establish the oil-rich nation’s abandoned cotton industry.

“But the locals did not know how to grow cotton well; we brought in Australian and Israeli cotton farmers to Nigeria to run our plantations of rain-fed cotton and show them how to do it – and they were fantastic,” Verghese recalls.

“Soon we had 10,000 hectares of cotton being grown by hundreds of small farmers who we provided with the inputs and training, and they grew cotton for us.

“We created an ecosystem that had huge benefits for both local farmers and the company. It showed me how transformative it could be. It was there I decided to go and set up something on my own.”

His admiration for Australian cotton farmers never left him. It is no coincidence cotton remains one of Olam’s six business priority areas and that Olam’s first acquisition when it entered Australia in 2007 was to buy ASX-listed Queensland Cotton and its processing gins for $134 million.

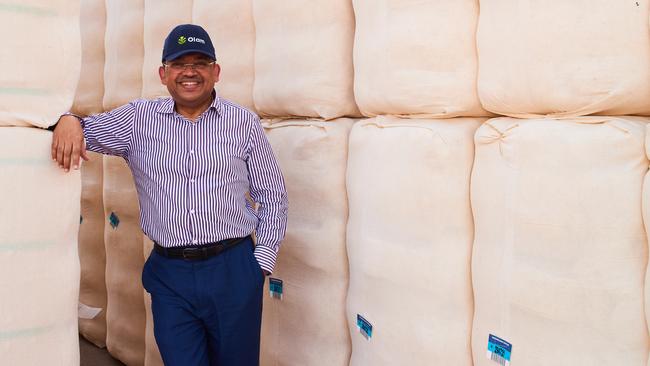

Olam has since grown to be a dominant player in Australia’s cotton industry, processing 800,000 to one million bales a year at its nine gins, producing 200,000 tonnes of cotton lint. And Verghese still never misses an opportunity to praise Australia’s cotton industry for its productivity, profitability and innovation. While Australian farmers face high input costs and are expensive producers of cotton, they are the most profitable globally. Yields top the world at 12-15 large bales a hectare, 30 per cent above other nations, and of unrivalled quality. Water and chemical use have been cut through innovation and ingenuity by more than 40 per cent in the past decade to the lowest among irrigated cotton nations.

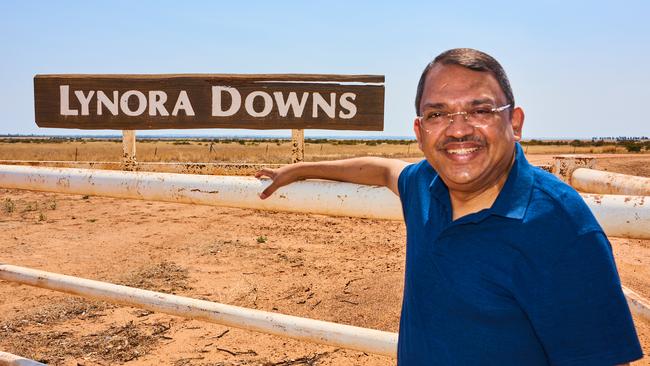

In 2016, to capture more of the farming profits inherent in successful cotton growing, Olam entered a joint venture with Australian listed agricultural property trust, the Rural Funds Group, on Lynora Downs, a prime $26 million cropping property in Central Queensland.

Olam now leases 1500 hectares of irrigated country on Lynora Downs to grow cotton and has invested considerable capital to expand its water reserves. The farming operation is run by Rural Funds Management, the harvested cotton is processed at Olam’s Emerald gin, and profits shared.

A new 4200-megalitre dam has also just been built on Lynora Downs – which, with its extensive overland flow, storage capacity of 14,500 megalitres and water licence entitlements of 18,185 megalitres, is often called a “mini-Cubbie” station – while a pivot spray irrigation system is being built to boost water-use efficiency by 20-25 per cent.

OLAM GROWS OR PRODUCES ENOUGH…

TOMATOES to top 3.2 billion pizzas

ONIONS to fill seven of every 10 hamburgers eaten in the US

COCOA for one in every three chocolate bars consumed globally

PEANUTS for peanut butter to fill 14 billion sandwiches

RICE to feed everybody at least one serving a year

COFFEE BEANS for every person in the world to drink two cups of coffee a week... and it is also the world’s biggest almond grower

NET DEFICIT

IN AN exclusive AgJournal interview with Verghese, in Emerald last December to visit Lynora Downs for the first time, the global agricultural leader did not hold back on the tough messages he believes all Australians – but especially farmers – must hear and act on.

A recent stark report by the United Nation’s Food and Land Use Commission – the ubiquitous Verghese sits on its board – found that while the total value of all food production globally is $US10 trillion annually, the real cost of producing that food including degraded land, forests, biodiversity and water resources was $US12 trillion.

“So effectively the current food and agricultural system is costing the world a net deficit, including natural capital lost, of $US2 trillion every year, and yet we still have people going to bed hungry and 52 million children worldwide who are malnourished,” Verghese says. “What I conclude is that the whole food and agricultural system is broken, and that if we have to feed 10 billion people by 2050, how do we produce 70 per cent more food without ruining the planet and destroying nature?”

Other compelling evidence of the need for complete agricultural change, says a passionate Verghese, is that agricultural and food production currently accounts for 25 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions (if land use change is included), 75 per cent of the world’s freshwater use and 75 per cent of biodiversity loss.

“It’s the invisible cost of food; the simple fact is that the food we grow and eat now is being subsidised by nature and costing the environment; it’s not sustainable and it’s causing irreversible climate change,” Verghese says. “The only way we can fix this broken system is to transform the way we do agriculture; producing more food and fibre with less waste, less water, less land and less emissions.”

It is also why Verghese, who is chair of the Geneva-based World Business Council for Sustainable Development wants Olam to become a key change agent. “For us and our farmers, a gathering scenario of climate change is real; we have seen so many proof points and evidence across all the countries, regions and commodities (that we grow and trade) that point to a climate emergency,” says a sombre Verghese.

“If there is no change or no attempt to halt carbon emissions, and it is just business as usual, we are looking at a very real, worst case “hot world” environment of up to four degrees increase in temperatures.

“We cannot allow this to happen – it would be a catastrophe for food production, security and water availability – which means every person, every company and every country must take unusual steps and at scale; we no longer have 30 years.”

Verghese last year announced Olam’s new mission as “Reimagining Global Food and Agriculture”, requiring a rapid and complete production system change. It has meant a total refocus on farming and processing sustainability and an end to the constant-growth mantra. “It’s not about selling more cotton or coffee, or producing more food without taking into account the natural cost. Our overriding purpose now is to change and fix the world,” Verghese explains.

PRESENT AND FUTURE

AT OLAM’S recent glittering 30th birthday celebrations in Singapore – when 600 guests were flown in for a weekend of lavish dining and entertainment – the carbon footprint of every flight taken, meal eaten, champagne flute drunk and limousine used was meticulously measured, and the carbon gases emitted offset by planting thousands of shade trees around Olam’s global pepper plantations.

A new phone app is also being trialled to allow Olam’s 70,000 employees to measure their personal carbon footprint, and then help them reduce it, or for Olam to offset it by planting millions more trees to store an equal amount of carbon.

Verghese is also determined to use the corporate power of Olam in all countries where it farms or processes food – including Australia – to advocate for a carbon trading price, carbon tax and mandatory carbon emissions and water-use disclosures on every food brand and product sold.

“He is an inspiring leader,” says Olam’s Australian chief Dall’Alba. “Sunny absolutely believes in everything he espouses and when he says Olam is now a purpose-driven company, that is no green-washing or PR spin.

“The Olam purpose now, through all levels of the company down to all its millions of farmers, is reimagining agricultural and food systems, which require we do more with less, and he is totally committed and genuine about that need.”

The first actions Olam took last year as part of its “reimagining” was to dump four of its commodity businesses. Sugar, fertilisers and rubber were classed unsustainable or without long-term futures. Most significantly, Olam is ceasing all timber and hardwood production from two million hectares of tropical native forests in Africa’s Congo. “They are all FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified sustainable, but long term if we want to be a world leader in sustainability, it didn’t fit squarely with that view,” Verghese says.

Another key focus is on being a smarter farmer. For example, Olam is a major US onion producer, supplying 70 per cent of onions used by takeaway hamburger chains such as McDonald’s, in dehydrated form.

A normal onion has a solid content of just 12 per cent. But by breeding a new variety of onion – non-genetically modified, adds Verghese – that has a 26 per cent solid content, it has reduced the land needed to grow its onion supply from 16,000 hectares to 8800 hectares, and saved more than 65,000 megalitres of water annually.

“And with less land and water needed to grow more solid onions, we have needed much less heat and energy to dry them out; so the greenhouse gas emissions embedded in every onion have dramatically halved – and Olam has saved $100 million a year,” says a satisfied Verghese.

In its extensive Australian almond groves, Olam is also using cutting-edge technology to reduce water use. By installing hi-tech water stress sensors that detect minuscule movements in tree trunk size, water is supplied through drip irrigation to every tree according to its individual needs. The result is boosted almond yields per tree using 20 per cent less water.

Around the world, where Olam sources crops such as cocoa, coffee, spices and cotton from other farmers, the company is now insisting on similar sustainable practices and environmental targets. It often shares in the cost of the technology or by microfinance lending, and assists farmers to gain organic, fair-trade and provenance certification.

“It means we can offer all our end-use customers such as the big chocolate manufacturers, coffee roasters or textile manufacturers full traceability and sustainability of the product, from its greenhouse gas emission footprint and farm provenance, through to land- and water-use intensity and food-waste metrics,” Verghese says.

“And by helping our farmers become sustainable and certified, we can get our customers to pay more, which we then distribute in value back up the chain to the source. It can be a real game changer for small farmers in countries like Africa.”

Verghese proudly points to an extra $US20 million of premiums it paid last year to its 650,000 cocoa farmers because of such initiatives. It has made farming families with small holdings more prosperous and slowed the drift away from rural areas to city slums.

CAPITAL-LITE

OLAM is also experimenting with different models of corporate farming, to reduce the amount of its capital tied up in expensive land or water licences; a system Dall’Alba calls “capital-lite”. The ownership of most of its Australian almond orchards and farmland, once trees are productive, is now in the hands of global investors or funds, such as Laguna Bay, Schroder Adveq and Canada’s Public Sector Pension fund, with almond production leased back to Olam long term.

In a separate deal last December, Olam also sold the vast 89,085 megalitres of permanent water licences attached to its Murray River almond farms to PSP for $490 million, under a 50-year guaranteed leaseback of the irrigation water to Olam. It booked a handy $311 million profit on the sale.

Verghese, not surprisingly, likes these sale-and-leaseback deals. “The source of value gains for Olam as a company is not capital land value increases or water trading – that is not our game,” he says emphatically.

“What we are good at is being a diversified tree cropping company able to offer our customers high quality produce; by being more asset-lite we can concentrate on our farming and free up assets to expand our scale and invest in new almond farms and technology.”

Verghese also has only praise for Australia’s water pricing and trading mechanisms within the Murray Darling Basin which he describes as “world best”, despite the shortage of irrigation water and its soaring prices, which have forced many irrigated dairy farmers out of business.

“Australia’s water trading market is sophisticated, developed and deep — it achieves a very balanced approach between the needs of farmers and stewardship of the environment,” says Verghese, while emphasising that Olam buys water only to use on its farms, and does not engage in water speculation.

“In times of change or scarcity, whether it be climate change or drought, it will always disturb and transform industries but we can’t bury our heads in the sand if something like dairy farming isn’t going to work anymore, or turn on ourselves and blame corporate farmers.

“Australia does not have a broken water trading system. It is actually working really well because, while the vast majority of water is owned and used by farmers like us, it is the 14 per cent of outside (non-farming) investment that helps in real price discovery, provides liquidity and gives scarce water a proper value that ensures it then goes to its best and highest-value use.”

A GLOBAL FOOTPRINT

A QUESTION Sunny Verghese gets asked most often, is “just who or what is Olam?”.

It’s a strange query given Olam International is the world’s third-largest agribusiness conglomerate, one of Singapore’s biggest 25 companies, employs more than 40,000 permanent staff worldwide and has a sales revenue in excess of $A32.5 billion annually.

It also grows and buys crops and raw food products from more than 4.7 million farmers, operates in 60 countries spanning Africa, Asia, South America, Russia, North America and Australia, and is a world leader in the trading and sale of key ingredients such as nuts, spices, chocolate, coffee, cotton, rice, dairy products and cereals – after processing in its 210 factories – to all the major food multinationals including Mars, Kellogg’s, Mondelez, Nestle, Unilever, Kraft Heinz, PepsiCo and Lavazza.

But Verghese, Olam’s co-founder and group chief executive, is neither surprised nor hurt that Olam’s massive global presence – it grows, produces and sells more than 32.8 billion tonnes of food products every year in a complete farm-to-fork supply chain – is not better known.

“Many people have never heard of Olam because we are not a brand, so we are not on the supermarket shelves or in the public eye,” he says.

“But we supply most of the key ingredients to the brands everyone knows; whether it’s cocoa beans to Cadbury, cereals to Kellogg’s or coffee beans to Lavazza. So while Olam is not ‘The Brand’, we are the brand behind the brand.”

Verghese delights in rattling off the statistics that show how remarkable and massive the business is. Today Olam and its supplier-farmers grow enough tomatoes, when made into tomato paste at its food processing plants, to top 3.2 billion pizzas every year.

Its onions fill seven of every 10 hamburgers eaten in the US. One in every three chocolate bars consumed globally contains Olam cocoa.

It grows enough peanuts, and turns them into enough peanut butter, to fill 14 billion sandwiches a year. It is the world’s biggest almond grower, and largest supplier of almond flour meal and the base ingredients for booming in-demand almond milk.

“Then when it comes to coffee we are by far the biggest (producer) in the world; we supply enough coffee beans for every person on this planet to drink two cups of coffee a week,“ Verghese says.

“And we provide enough rice to feed everybody on this planet with at least one serving a year.”

Olam International and its assets have a capitalisation of $A6.3 billion, including the 2.4 million hectares of farmland it owns.

It is listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange, where it is 53 per cent-owned by the Singapore government’s investment arm Temasek and 17.4 per cent by Japan’s Mitsubishi Corporation. Verghese and his co-founder retain a 7 per cent stake.