China free-trade: Why Australian agribusiness still struggles to deal with the red giant

Five years on from the Australia-China free-trade agreement, dealing with the world’s biggest nation remains a challenge.

STEP into any Chinese supermarket and you’re greeted by an array of international produce, the likes of which would make the United Nations proud – Australian beef, French bread and butter, American soy and Canadian milk and cheese.

It is a stark reminder that five years after Australia signed a free-trade deal that was meant to put us in the box seat with China, we are one of many players in the country.

“We’re not the only show in town,” says Peter Arkell, an Australian businessman who has been based in Shanghai for 17 years. And, indeed, grabbing the limelight in the “show” appears to be getting harder, not easier.

Australian farmers have been sold the narrative that China is an exporter’s utopia; a bountiful land where, if you can get a foot in the door, countless riches await.

But it isn’t. Since 2015, Australian businesses have discovered the heavy hand of Chinese bureaucracy, political power plays and disease outbreaks are more challenging than any import-duty cuts.

In his time in Shanghai, Arkell has seen many businesses – both Australian and others – try to take on the Chinese market. The only way to succeed, he says, is for companies to pull their socks up to make a mark in a complex market.

The Lynch Group, one of Australia’s largest flower suppliers, has got the memo. It has built two large flower farms in rural Yunnan province, growing millions of stems every month. It also imports Australian native flowers to sell to Chinese consumers.

Other countries are also proving that a China strategy is doable. “Germany is really great at their engagement with China,” Arkell says. “The Germans have got a really great presence here. As a result, those companies have become extremely profitable.”

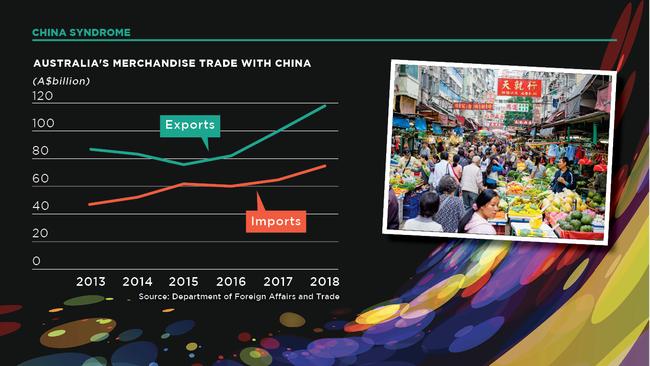

CHINA is Australia’s largest trading partner by far, buying a staggering $116 billion of Australian exports in 2017. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade figures show China bought about $13 billion of our agricultural produce in 2017.

As Arkell points out, a domestic market of 25 million people is never going to satisfy Australian farmers, whose ethos has been to feed and clothe the world since those first bales of wool made their way to England in the 1700s.

“Imagine Australia if we didn’t have the trade that we do have? What would our economy be like? We are a trading nation, and we get the most bang for our buck by being a great trader.”

Since the free-trade agreement came into effect, the value of Australian exports into China has soared. When signed in 2015, the value of exports into China was just shy of $80 million. Three years later in 2018, the value of Australian exports into China exceeded $100 million.

No doubt the past five years have proved profitable for Australian producers exporting into China. But this doesn’t mean Australia’s complex dealings with China disappeared the moment the ink was dry on the deal.

Australia, amid regional security tensions, still finds trading into China difficult, no matter how hard one works on the ground to establish connections and break into the market.

It took about a decade for China to come to the table and sign a memorandum of understanding with Australia to import citrus fruits in 2014.

But it was worth the wait. Australian horticultural exports, citrus included, topped $1 billion in 2019, dramatically up on $13 million in 2010.

Yet despite the success of citrus in China, access for other fruits and vegetables such as blueberries, avocados and potatoes is still limited. Australian blueberries have been trying to gain access into China since 2010, while apples have been waiting for guaranteed market access since 2006.

IT IS not just bureaucracy that can be a stumbling block.

African swine fever – which has hit China hard – and coronavirus – which appears to be hitting even harder – prove that dealing with China is a fickle business.

Plus, political relations between Australia and China have been strained in recent times. The 2018 decision to ban Chinese telco company Huawei from supplying 5G internet infrastructure in Australia amid intelligence security concerns, for example, soured relations between the two nations. And before that was the 2009 arrest of Rio Tinto employees in China, including Australian citizen Stern Hu, on suspicion of selling state secrets.

China is known for being ultra sensitive, and struggles with how open Australians are when expressing themselves politically. These factors combine to create tension, testing the boundaries of the Australian-Chinese relationship and fostering suspicions on both sides.

“It has been most unusual how few senior (Australian) federal people have been through China in the last two years, or even longer. Whereas before we had almost a passing parade. If you go back to previous years, from Tony Abbott and Gillard, and Rudd before him, each had an extremely high presence, and we just haven’t had that since mid-Turnbull.”

Beijing-based business media group Caixin says Australia is “between a rock and a hard place” when it comes to juggling relationships with China and the US.

However, according to Caixin, Australia remains widely recognised in China as an important business partner.

“Mining, dairy and tourism … you cannot ignore the market, definitely the Australian market is a must-go area,” a spokesman says. But the 5G decision “wasn’t healthy” for ties with China, Caixin says.

Arkell hopes the Chinese appetite for Australian products “whether that be minerals or agriculture” won’t be diminished by “what has been at times a not very good political friendship”.