Inside Arkstone: Bid to save victims of Australia’s online child abuse ring

It was the Aussie accent which rocked the battle-hardened cop. Find out how authorities rescued 56 children and 11 animals while investigating the country’s largest online child abuse ring.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was the accent which rocked the battle-hardened cop whose days were spent chasing the filthiest predators. And it only took a few words to deepen her chills and heighten her anxiety.

“These children were clearly Australian,” AFP Detective Leading Senior Constable Kate Laidler recalled.

“We could tell from the accent and material, and it was the most horrific material I have ever encountered, and such a huge volume.

“When it’s Australian, we are acutely aware we might be the only people who are looking for these children and it might be the only opportunity to rescue them. You feel this sense of pressure – and it adds another layer of complexity to what we were seeing.”

And so the chase quickly became two pronged with an enormous sense of urgency – the logical hunt for the offenders and the heartbreaking search for their victims.

They were the two most challenging parts of the Australia’s largest online child abuse investigation, Operation Arkstone.

And now, after NewsLocal has revealed its inner workings and the heartbreaking stories of its victims and their families, frontline workers have shared insight into the tedious difficulties of finding the lifesaving needle in a haystack.

Each needle was a real child being abused inside homes around the Australia. The haystack was made up of literally millions of anonymous videos of this disgusting abuse, being exchanged via chat platforms such as Snapchat to perverts around the world.

Child protection has occupied much of Const. Laidler’s 23-year-long career. She was the main victim identification specialist with Operation Arkstone, which saw 26 men arrested and 56 children saved, not counting the 156 international referrals.

When the AFP discovered the ring in early 2020, Const. Laidler was shocked at the sickening abuse that was traded online like currency on a scale she’d never before seen.

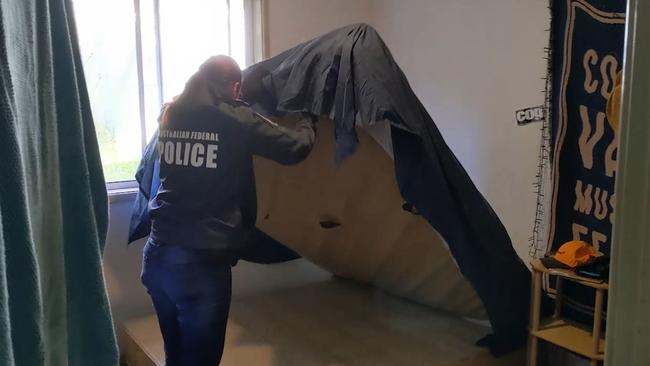

Whenever Operation Arkstone ordered a search of a suspect’s home, Const. Laidler’s team was faced with investigating the vast collection of material seized. Her role was to look for clues in time to save the children in them.

“For obvious reasons, these perpetrators don’t reveal identifying information,” she said.

She used a sophisticated and specialised victim identification software that can filter huge amounts of data. She said it meant, thankfully, it was not always necessary to watch every video – though often she would still spend hours and hours on end doing so.

Her team used a mix of this software and the human eye to look for technical and audiovisual cues to determine where the material was filmed. Visually, they’d focus on a piece of furniture or clothing to decipher where it was sold. They also listened out for clues such as accents.

Using these methods, police saved dozens of Australian children violated in the millions of pieces of abuse material exchanged in the child abuse ring.

“The resilience shown by everyone in that investigation and the people I worked with who were so motivated to rescue those children will always stay with me,” she said.

“We can’t change what happened to them in the past but we can change what their future holds.”

On the topic of how she coped mentally working on such a dire and upsetting topic, she admitted it inevitably impacted her. But she has learned, through determination and practice, to use different mental strategies taught via psychosocial support within the AFP.

A crucial one has been mindfulness.

“When we walk out the door, that’s it. We have a practice about enjoying the walk to the car; looking at the flowers, feeling the wind,” she said.

“And it has to be a conscious decision to say ‘I’m not going to think about anymore’, because you can’t carry it with you.”

The children in the videos could not be saved without the work of Const. Laidler’s team. But when they’re done, the mission of Operation Arkstone is far from over.

A federal agent who knows that all too well is AFP Child Protection Operations officer, Constable Emily McFarlane.

Once her team has received enough victim identification information to know where the child is, they pounce on the potential offenders with search warrants and visit the victims’ homes.

Const. Laidler said “dropping the bombshell” on parents and guardians whose children have been abused and interviewing the kids and teenagers was heart-wrenching.

“It’s one of the worst thing to do, speaking to a child who’s disclosing things to you that they don’t want to talk about,” Const. McFarlane said.

“It’s almost relieving to have them be able to say things to me in a safe space and build enough trust, but also quite upsetting because it is distressing for them as well.

“I’m the one that’s listening to them tell that story and I’m upset. So I can’t imagine what it’s like for them to have actually experienced it.”

From Const. McFarlane’s experience, kids as young as four and five would often understand what they’d suffered was wrong. Some didn’t reveal what happened because they wanted to protect the offender who groomed them into trusting them. It was devastating to see them get upset when they learned their abuser was going to jail.

Others got embarrassed, so Const. McFarlane would draw pictures with them to increase their comfort levels. Some either didn’t think what happened was bad or didn’t remember it.

Const. McFarlane said many older kids showed shame – even though such a feeling should only ever lie with the perpetrator.

“I can see why people take a while to open up to the police and say this happened to me 10 years ago, I’m a historical child sex offence victim,” she said.

“Because it’s so much shame. You know, they build up this trust with someone.”

Somehow, Const. McFarlane could seamlessly transition from speaking to these children and feeling raw devastation and shock, to interviewing offenders.

When she’d burst into the homes of perpetrators, she said they’d show a mix of shock, upset, anger and denial. Most would either expose or feign regret.

It was crucial Const. McFarlane treated them with some respect in the hope they’d reveal the whereabouts of other offenders and victims.

“What good is it to go in a door and scream at them?” she said. “They might tell me if they know of other children being harmed.”

When she first joined the police force in 2018, Const. McFarlane thought she could never work in child protection, because it would be too difficult.

“Then when I started working up in the office, and had to assist with some child protection and search warrants, I went, ‘you know what, this is actually a really rewarding area, because you’re making a difference in bringing an actual body off the street’,” she said.

Like Const. Laidler, Const. McFarlane had to watch many videos of child abuse. She’d adapted similar mental health coping mechanisms.

Living near the ocean helps, she explained. After leaving the office, she’d switch off her work phone, walk along the beach with friends and family and generally avoid work chat or any entertainment with heavy content, such as true crime podcasts.

“It sounds corny but I surround myself with nature … and people who are close to me,” she said.

“If I’ve had a really bad day I’ll vent, but not go into details, obviously.”

After so much time and effort spent tracking down victims and countless difficult conversations, Const. McFarlane tried to remember that once it gets to court, the type and length of penalty served is out of her hands.

“Whatever happens, happens, and I can say with hand on heart that I’ve done everything that I can and put my heart and soul into that brief of evidence,” she said.

“These people might receive a custodial sentence and go to jail for three years. That victim has got a lifelong sentence.

“At least there are less of these men on the streets because of our work. That’s rewarding.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Inside Arkstone: Bid to save victims of Australia’s online child abuse ring