Guyra Ghost of 1921 led to local hysteria and still remains a mystery

As Sherlock Holmes and spiritualism became popular, a ghostly case in the NSW town of Guyra led to hysteria spreading throughout Australia.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A capacity audience crowded into the Sydney Hippodrome for the premiere of John Cosgrove’s silent film, The Guyra Ghost, on June 19, 1921.

Showing mere weeks after the events it purported to cover, the film was a rushed three days in the making and promised to feature Minnie Bowen herself, the 12-year-old girl who was at the centre of one of Australia’s biggest ghostly mysteries.

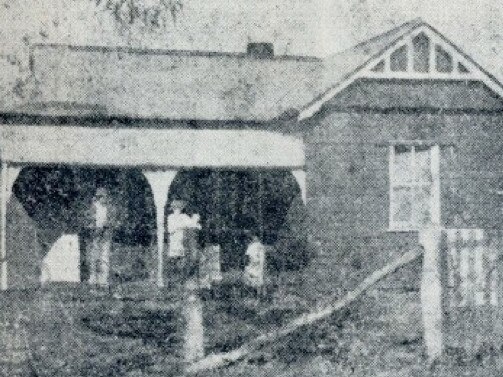

The silent film is lost to us today, but it is said to have been filmed at the actual weatherboard cottage just outside Guyra in northern NSW where, for several weeks in April 1921, rocks and stones were thrown at the walls and through the windows of the home, seemingly by an invisible hand.

It is the subject of a two-part episode on historian Michael Adam’s podcast Forgotten Australia, which reveals the hysteria that took over the town and spread throughout Australia.

“The Guyra Ghost remains Australian history wrapped in mystery,” Adams concludes, though his true sentiments fall more on the side of hoax than haunting.

The bizarre events began on April 1, 1921, when Minnie reported being followed by a “creepy man” close to her home and who threw stones at the property. Soon after, a shower of rocks is said to have fallen on the house and a heavy railway sleeper kept appearing by a window of the home despite being repeatedly removed by police.

Police watched the home in the hope of catching the perpetrator and one night they reported hearing a rifle discharge and a bullet hit the home. But the shooter could not be found.

By April 5, local constables were joined by four civilians who watched the home from both the inside and outside. During that time, the home was again hit by numerous stones.

Again, they could not find the perpetrator. On April 6, a window was smashed by a rock right in front of the sergeant’s face and up to 20 missiles are reported to have hit the home.

Around this time, it was noticed the bombardment seemed to occur in whichever room young Minnie occupied. As a result locals and police began to watch her carefully to ensure she wasn’t involved.

The following night she was taken to a neighbour’s home while up to 70 civilians and police watched her house.

The stones stopped.

By April 7, the Guyra Argus reported on the curious goings-on and the story spread as far as Sydney and beyond. With Minnie back in her home, the stones soon started up again despite the fact she was being watched by police.

That evening around 40 volunteers joined police in an attempt to catch what they considered to be a prankster, but every window ended up smashed by an apparently unseen assailant.

Over the following days the number of people watching the house passed 80 and a loud banging was also reported in the home that could be heard 100 yards (91m) away.

The situation intensified on April 13 when spiritualist Ben Davey came to the home and held a seance in front of a crowd. He was convinced the ghostly actions were the work of Minnie’s half sister, May, who died suddenly in January that year. He urged Minnie to communicate with her dead sister and she subsequently passed on a message to her mother that May was well and happy in the afterlife.

But the stone throwing and loud banging continued.

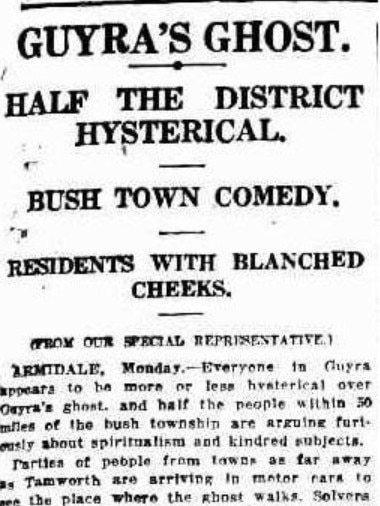

A Daily Telegraph headline screamed “Guyra Ghost – Half the District Hysterical” on April 19.

Before the month’s end, Minnie was spotted throwing a few stones at the house and she later admitted she was responsible for some of the mischief, but not all.

“What was fascinating was how it just escalated as people piled on – locals, police, reporters, various spiritualists and, of course, copycat hoaxers,” Adams says.

“There was an ‘official’ explanation and everyone seemed to shake it off and forget about it.

“But as my podcast shows, it never really was properly explained.”

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

SPIRITUALISTS ON THE RISE

In order to understand how willing people were to jump on the ghost bandwagon in 1921, it is worth noting the rise of spiritualism in Australia at that time, says Forgotten Australia podcast host Michael Adams.

Spiritualists believe they can communicate with the dead and it was gaining followers thanks to the likes of Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle who toured Australia just before the Guyra Ghost events occurred.

On November 28, 1920, about 3500 spiritualists held a reception for Doyle at Sydney Town Hall to mark the start of his tour across Australia and New Zealand.

OTHER BUMPS IN THE NIGHT

In his two-episode deep dive into the topic of the Guyra Ghost, Forgotten Australia podcast host Michael Adams reveals it was not a lone incident.

In 1887, mother of 13, Mrs Large, reported falling stones and ghostly missiles at her home near Mudgee in central west NSW which went on for months.

In Enmore in 1894, a row of three terraces came under attack by a seemingly invisible stone-thrower. Up to 1000 people gathered outside the homes over the two weeks but in the end it was found to be the work of the mischievous 12-year-old resident of one of the terraces, Emma Greaves.

Notorious rep of NSW hangman debunked

There are two ways to bungle a hanging. If the length of rope and weight of the person being executed are wrong, you can strangle them — resulting in a long and drawn out death, or decapitate them completely.

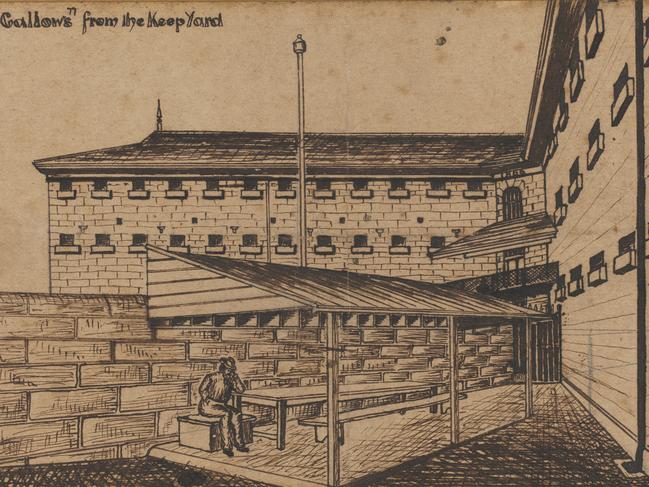

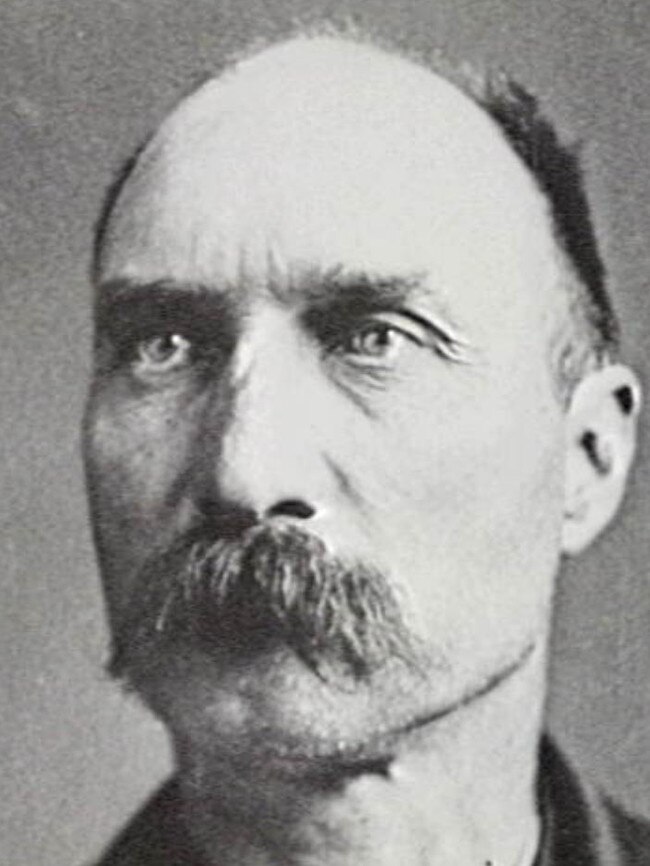

This second scenario is (almost) what happened when notorious hangman Robert “Nosey Bob” Howard executed convicted murderess Louisa Collins in 1889, partially severing her head in front of the gathered crowd outside Darlinghurst Gaol.

The bungled hanging would mar Nosey Bob’s career as state executioner, a job he held for almost three decades, and give rise to one of the most common myths about the misunderstood hangman.

“I was doing some research on how women were treated prior to Federation and looking into the case of Louisa Collins when the name of Nosey Bob and his bungled hanging came up,” says historian Rachel Franks, who has just released a book called An Uncommon Hangman.

“I started looking into him and there were many articles on how he was deliberately cruel and a disgrace of a hangman. What I found when I dug deeper though, was that he had only a few errors, like the hanging of Louisa Collins, he was never drunk at work, was very careful on the scaffold and actually tried to add some dignity and compassion to his work.”

Franks says it turned out to be just one of many myths associated with the man who performed one of the most detested jobs in the country.

Robert Howard was born in Marham, England in 1832 and went on to become a cab driver, like his father.

In 1858 he married Jane Townsend in London and in 1866 the couple relocated to Brisbane with their three children. A year or two later they moved to Sydney, had two more children, and Bob revived his career as a cab driver, establishing a business in the inner city.

Most public accounts claim Nosey Bob lost his nose when a horse kicked him in the face, but Franks says she uncovered the real reason he came by his infamous moniker, a secret she guards carefully in order to reveal it only to readers of her book.

His disfigurement, which he chose to leave uncovered, could have been the reason his work as a cab driver dried up. Franks speculates his exclusive clients may not have liked the gruesome disfigurement.

Either way, Bob became an assistant executioner in 1876, and after just three hangings, was promoted to the top job.

He went on to hang 62 people throughout his time as state executioner, including a few notorious names. Apart from Collins, he also executed the man often referred to as Australia’s first serial killer, Frank Butler in 1897; the baby farmer John Makin in 1893; and Indigenous outlaw Jimmy Governor in 1901.

“Nosey Bob had the most hated job in NSW so they didn’t collect the type of information you’d expect of a government servant,” Franks says, describing the challenges she faced researching her book.

“There were no real personnel records kept. I had to rely a lot on newspaper articles and some archives.

“But what I did find was that there were a lot of myths about him; a hangman without a nose was an easy scapegoat for abolitionists who couldn’t go up against the entire justice system.”

One of the myths is that he had three lonely daughters who became spinsters because nobody wanted a hangman as a father-in-law.

Franks says it’s not true. One daughter married happily and had a family in the Southern Highlands, another tragically died as a teenager and the third married a few times and, though never settled, was not a spinster.

It is also said his wife died of depression, unable to contend with her husband’s career choice. Not so, says Franks, she died of heart disease. Bob retired in 1904 and died in 1906, aged 74.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

MAN BEHIND THE NOOSE

Franks’ research uncovered a man who loved his family and was a kind and compassionate member of society.

When not busy at the gallows, Nosey Bob went to Darlinghurst Gaol to tend a garden, look after the chickens and even attend to the sheriff’s horse and buggy. When there was no work at the jail, he would go to the Darlinghurst Courthouse restaurant and offer to clean dishes.

Franks says he would always stand for women on the tram and was known to help the destitute families of the men he executed out of his own pocket.

BABY KILLER EXECUTION

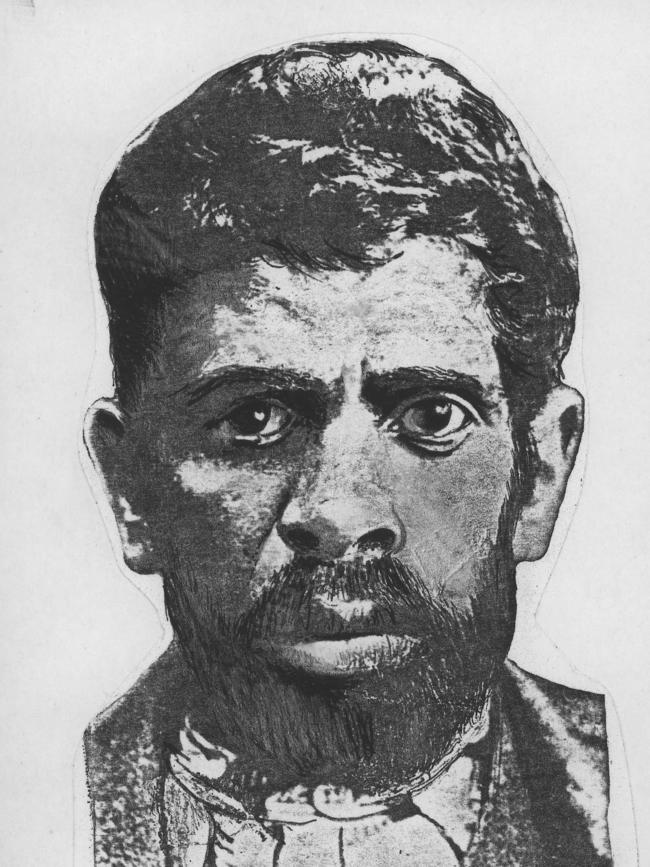

One of the most notorious criminals Nosey Bob executed was John Makin, who together with his wife Sarah, was found guilty of the death of baby Horace Murray in March 1893.

The Makins had offered to adopt Horace after his desperate mother posted a newspaper advertisement seeking a better life for her son.

When the bodies of 13 babies were found buried in three of the Makins’ inner-city homes they were charged with Horace’s murder on the strength of his mother’s testimony. John was hanged in August 1893 and Sarah sentenced to life in prison, but paroled in 1911.

Originally published as Guyra Ghost of 1921 led to local hysteria and still remains a mystery