Two Bali bombing survivors reunite; AFP helped solve the Bali terrorist attack

Lynley Le Grand has been reunited with her “guardian angel” after a horrific night in Bali bound her with fellow Aussie Sevegne Newton for life.

Behind the Scenes

Don't miss out on the headlines from Behind the Scenes. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It took 17 years, but Bali bombings survivor Lynley Le Grand this week was finally back in the arms of her “guardian angel”.

The Australian was a university graduate without a care in the world, dancing the night away at Paddy’s Bar on October 12, 2002, when her life was forever changed.

Fellow Australian Sevegne Newton came to her rescue that night and has been credited with saving her life.

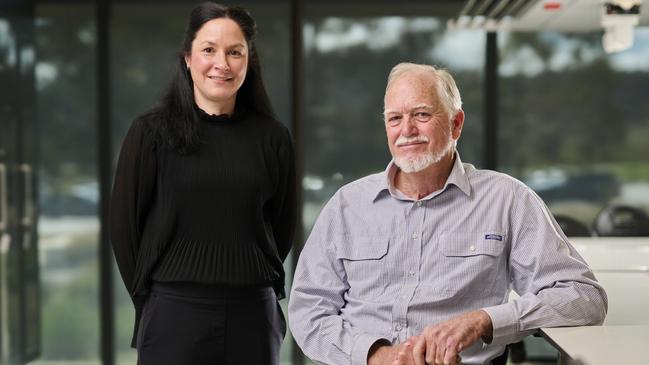

Lynley, 42, and Sevegne, 60, reunited in Bali last week and sat down with the Sunday Herald Sun to talk about how a night in Bali bound two strangers for life.

“I literally got on the back of a bike after having dinner at Hard Rock Cafe and went to Paddy’s Bar and about 20 minutes later, the bomb went off,” said Lynley, then Lynley Huguenin.

The intensity of the blast flung her metres across the bar, as she and her three friends were dancing — only a metre away from the suicide bomber.

She suffered burns to 30 per cent of her body and was peppered in shrapnel.

Luckily, Lynley and her friend Kim could drag themselves out of the rubble and were helped to their hotel by a young boy with a bike.

But little did Lynley know, she was about to meet her true saviour.

Sevegne was four floors up in her hotel room when the two young women arrived at the hotel. She can vividly remember the screams.

“I looked over the balcony and saw security guards literally with their hands in Kim and Lynley’s burning flesh,” Sevegne recounted.

“I could see the blood dripping off them. I could see the skin falling off them.”

She ran downstairs, followed the trail of blood to a hotel room door and frantically knocked.

When Lynley opened the door and saw Sevegne, she knew her “guardian angel” had arrived.

While Kim’s parents were in Bali, 22-year-old Lynley was on the island alone.

“When she opened that door, I think she realised there was somebody there for her,” Sevegne said.

“I remember her looking at me and saying: ‘Please don’t leave me.’”

“And all I could say is: ‘I promise I won’t.’”

The women ended up at Sanglah Hospital, the largest hospital in Bali.

But the employees were so hopelessly overwhelmed, Sevegne had to step in as nurse.

“I got told to peel Lynley’s skin off,” she said.

It soon became clear the pair could not stay there, so they travelled to the Bali International Medical Clinic.

In the meantime, Sevegne got so desperate for information, she thought to ring newspapers back home.

When she rang the Herald Sun, a young journalist answered the phone.

“He got on the phone and I said: ‘I need your help.’” Sevegne said.

That was all the reporter needed to hear. He got to work to find out how Lynley could be brought home as soon as possible.

He soon discovered a Hercules transport aircraft would be landing at a military air base next to Denpasar Airport to evacuate Australians.

Officials had visited Sanglah Hospital to decide who would be travelling on the Hercules but since the pair had left that hospital, they had missed out.

But the reporter rang Sevegne and told her where and when the Hercules would land. Lynley was the first victim carried aboard that plane.

Sevegne was grateful someone was looking out for her, as she looked out for Lynley, although she was terrified officials would remove Lynley, since she had not been chosen to fly.

“I don’t think she knows but I sat there until 11pm, until the plane took off, so that I knew she was gone as well,” she said.

“Lynley and I are both fighters.

“There was a real comfort in that because I knew she was going to fight as hard as I was going to fight to make sure that she got out of this.”

Despite the blistering and the swelling, Sevegne held on tightly to Lynley’s hand for many of the hours they spent together.

In a letter published in the Herald Sun in 2003, Lynley wrote about her “guardian angel” and said: “Without you, I don’t know if I would have made it.”

From Denpasar to Darwin, Lynley was soon in Melbourne and en route to the Alfred.

“Within half an hour of landing in Melbourne, we were processed through emergency and into surgery,” Lynley said.

“They were waiting with a full team, ready to do skin grafts.”

One week later, Sevegne travelled to Melbourne to visit Lynley in hospital as she began recovery.

Two decades on, Lynley’s love for Bali has never wavered.

She now runs hospitality venues on the island with her husband, Michael, with the business going from strength to strength.

“We went from 55 staff here to 350 staff in the last couple of months,” Lynley said.

But she is most proud to be a mum to her stepson and her three children, and a wife.

For Sevegne, life is spent living in Byron Bay, running a small candle business.

The two women last saw each other in Byron Bay around 2005, as life got in the way of them reuniting for the 10th anniversary.

But nothing would stop Sevegne from being reunited with Lynley this time around, especially since Lynley is now the age Sevegne was when she rescued her.

And so for the first time, she travelled to Bali to be with Lynley.

“I just knew I wanted to be where she was,” Sevegne said.

“I remember Lynley’s courage, her tenacity, her sense of humour and I knew she was an absolute survivor.

“To see her now, to see all the things that she’s accomplished, it makes me so happy.”

Listen to the AFP’s new podcast Operation ALLIANCE: 2002 Bali Bombings

HOW AUSSIE COPS HELP CRACK BALI BOMBING CASE

It was the phone call that would change Sarah Benson’s life.

As a trainee chemist with the Australian Federal Police, Benson was working a Sunday shift when the lab phone rang.

“First it was one of my friends or colleagues to say ‘have you heard the news?’ And then the phone just kept ringing,” Benson, who had joined the AFP only three years earlier, recalled.

It was just after 11pm on Saturday, October 12, 2002, when a man wearing an explosive device filled with metal shrapnel blew himself up in Paddy’s bar in the Balinese tourist town of Kuta.

Seconds later, as terrified people fled on to the street, another powerful bomb exploded in a car parked outside the nearby Sari Club.

The bombings killed 202 people, including 88 Australians, in a terrorist attack linked to the Jemaah Islamiah Islamic extremist group.

Benson and her then boss, senior AFP chemist David Royds were crucial to solving what was one of the first investigations of its kind – where forensic chemists were sent to the frontline in a mobile laboratory.

Royds, who first came up with the theory the explosions had been the work of suicide bombers, arrived in Bali two days after the attack.

Benson, who was just 25, would join him later that week after spending the first few days searching for explosive residue on victims’ clothing as their bodies were returned home to their grieving families.

As a young trainee, she said she was “probably a little bit protected” in the lab in Canberra before being sent to Bali.

“But over there, you know, you’re living and breathing it, you’re feeling it, you’re seeing what’s there. It’s a little harder to disconnect from that,” she said.

PODCAST: GUARDIANS OF THE DEAD: THE BALI BOMBINGS

A police headquarters had been established at Kuta’s Kartika Plaza Hotel, where the small team of forensic chemists built a temporary lab.

The forensics team embarked on a months-long investigation with interstate and international police colleagues which involved multiple trips – often at a moment’s notice – between Bali and Canberra.

“In the early stages, you’re chasing red herrings all the time,” Royds said, recalling a moment in which he thought a linked, non-fatal bombing at the US consulate in Bali might have been connected to the Irish Republican Army.

Neither Benson nor Royds will forget their first visit to the obliterated nightclub Paddy’s.

“You can never undo that tragedy for the victims and their families. But I think (there was) a sense we were able to help in some way to support justice,” Benson said.

Royds ended up being called to give evidence in court against bombmaker Umar Patek, who was convicted for his role in the bombings.

“It gave me a lot of closure,” he said.

“I was actually able to get up and say things that I felt as though the judges should know about for the sake of the victims.”

Benson and Royds were joined by a string of Australian Disaster Victim Identification specialists who would help bring those terrorists to justice.

Professor Chris Griffith, a forensic odontologist, and the first scientific vice chairman of Interpol’s Disaster Victim Identification Committee, was sent to Bali to help identify people using their teeth in Operation Alliance.

Professor Griffith, from the Westmead Centre for Oral Health, said “during the 2002 Bali bombings, 60 per cent of the victims were identified with dental evidence within the first two weeks”.

“Some of the more difficult cases were identified through DNA,” Prof Griffiths said.

He was joined by police from around Australia, including Brisbane based Senior Sergeant Ken Rach, who had more than 20 years’ experience in DVI and played a major role in the development of the response plan within hours of arriving.

He was also quickly co-ordinating the post mortem/mortuary phase of the response.

Sen Sgt Rach was the only police officer in Australia at the time dedicated to a full-time DVI position.

He returned to Bali four times to help and was awarded an OAM for his work.

The Indonesian government has announced Patek will be granted early parole halfway through his 20-year sentence.

More Coverage

Originally published as Two Bali bombing survivors reunite; AFP helped solve the Bali terrorist attack