‘23 year low’: Freak climate event spells catastrophe

A freak weather event in one of the world’s most densely-populated areas is threatening two billion lives.

It has stopped snowing in the Himalayas.

As a result, the water supply two billion people is under threat.

The mountain range reaches 2500km from Afghanistan in the west to Myanmar in the east.

Its high peaks and valleys are covered in ice – or should be.

The annual cycle of melting snow feeds 12 major river basins that wind their way across the Central and East Asian landscape.

These are the major water sources for a dozen nations But measurements have revealed a steady decline in snow falling across the Himalayas in recent decades.

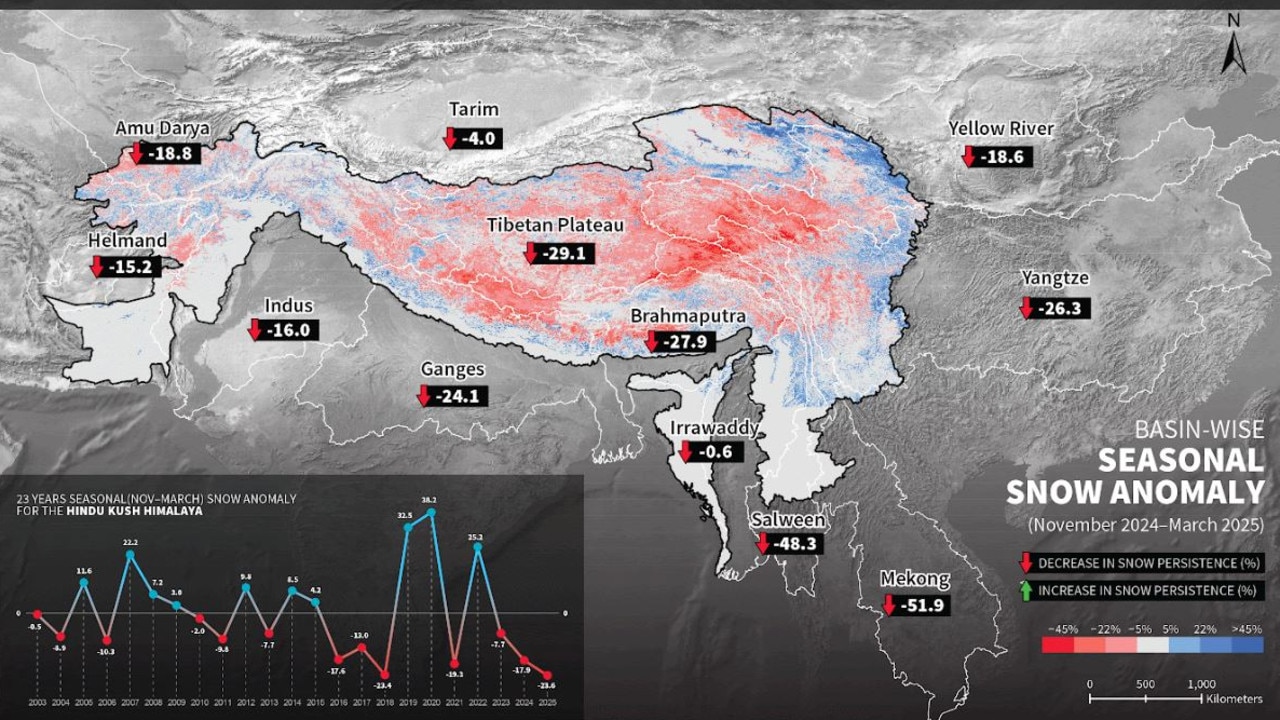

This season, it tumbled to an overall 23-year low.

“This is an alarming trend,” says International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) scientist Sher Muhammad.

“We are observing such deficit situations occurring in continuous succession.”

Some rivers are suffering more than others.

The HKH Snow Update 2025 report reveals snow catchments for the Mekong and Salwen Rivers that feed into Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia are worse than 50 per cent lower than average.

China’s Yangtze catchment has 26 per cent less snow. The Ganges River of India and Bangladesh is down 24 per cent.

As is the Indus that feeds Kashmir and Pakistan.

The reduced snowfalls would not be a problem if it were a one-off event, but the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) says this has happened in five out of the past six years.

It’s an acceleration of a trend observed over the past quarter century and the implications of this trend are enormous.

“Australian policymakers are vastly underestimating how climate change will disrupt national security and regional stability across the Indo-Pacific,” warns Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) analyst Mike Copage.

Drying Up

Less snow in the Himalayas means less spring melt and less insulation for any ice or glaciers beneath.

Less spring melt means less water flow and that, in turn, means less soak to refill groundwater basins.

Snow isn’t the only source of water for the major Himalayan rivers. While every river differs, snow, on average, contributes to about a quarter of all annual water runoff.

But researchers say there is no doubt that ongoing snow deficits are contributing to changing flow patterns and falling water levels.

“(This means) early-summer water stress, especially for downstream communities, already reeling under premature and intensifying heat spells across the region,” ICIMOD says.

China’s Yellow River Basin is a case in point.

Its snow persistence (how long snow remains on the ground) fell from 98 per cent above average in 2008 to -54 per cent in 2023.

“The basin continues facing deficits (albeit at -18.6% in 2025),” the report states.

“Such sustained deficits strain agriculture, hydropower, and water availability.”

It’s a similar story for China’s Yangtze Basin.

This year’s snowfall vanished 26 per cent faster than average.

“Steadily declining snowpack jeopardises hydropower efficiency of the Three Gorges dam,” the report warns.

It’s a similar story for all Himalayan-fed hydropower projects and agricultural regions.

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) is urging Asian nations to take immediate action.

And spending billions on improved water management systems, stronger drought preparedness, better early warning systems, and greater regional co-operation is just the first step.

“Carbon emissions have already locked in an irreversible course of recurrent snow anomalies in the (Himalayas),” warns ICIMOD Director General Pema Gyamtsho.

“We urgently need to embrace a paradigm shift toward science-based, forward-looking policies and foster renewed regional co-operation for transboundary water management and emissions mitigation.”

But the experience isn’t unique to Asia.

The Aral Sea between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan has shrunk to a fraction of its original size in recent decades.

Russia’s Caspian Sea – the world’s largest lake – is in rapid retreat and Lake Chad in central-west Africa has evaporated by up to 90 per cent.’

Worse to Come

The vast Himalayan snow and rainfall catchments are subject to various climate influences.

Previously, more predictable weather patterns offer little hope of improvement in Southeast Asia’s water supplies.

This year’s La Niña weather pattern vanished after just a few months.

This is the cold phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation cycle, a long-observed natural temperature exchange across the Pacific Ocean.

A warm El Niño generally switches to a cold La Niña every two to seven years.

La Niña was due to replace the last El Niño in mid-2024. It didn’t arrive until December.

Now, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports it evaporated in March.

“After just a few months of La Niña conditions, the tropical Pacific is now ENSO-neutral, and forecasters expect neutral to continue through the Northern Hemisphere summer (Australian winter),” says University of Miami researcher Emily Becker.

Historically, La Niña is associated with increased rainfall in Southeast Asia and Indo-China.

An ENSO neutral phase generally brings much less predictable weather, NOAA warns.

“El Niño events can include drought and extreme heat, while La Niña events can include extreme rainfall and severe flooding,” a Perth USAsia Centre report states.

“It is predicted that even 1.5C of global warming will double the frequency of extreme El Niño events and magnify the rainfall variability of the El Niño – La Niña weather cycle.”

Asia is suffering the most from global climate change, observes the UN’s World Meteorological Organisation.

Successive droughts have produced a particularly high number of damaging heatwaves.

These have been topped off by destructive storms and flood and it’s turning into a relentless trend.

The Asian Development Bank has predicted that rice yields from Indonesia to Vietnam will fall 50 per cent by 2100 without urgent and expensive climate adaptation measures.

“While the physical impacts of climate change are already intensifying, the most concerning outcomes globally will arise from social, economic and political disruptions which are far more difficult to predict or manage than isolated disaster events,” warns ASPI’s Copage.

“Given an already unstable global context of rising geopolitical tensions, climate impacts will only magnify this volatility.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social

Originally published as ‘23 year low’: Freak climate event spells catastrophe